Saturday, July 24, 2021

Friday, July 23, 2021

First map of marine structures shows how much we've modified the oceans

From NewAtlas by Nick Lavars

With our long history of altering the environment through manmade structures, we humans sure have made our mark on the Earth in our relatively short time here.

Scientists in Australia have turned their attention to what this perpetual development means for the world’s marine environments, calculating the extent of our construction footprint on the oceans for the first time ever.

The research was carried out at Australia’s University of Sydney and the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, with the team collating data on marine-built structures of all kinds.

These include oil rigs, wind farms, the length of telecommunication cables, commercial ports, bridges and tunnels, artificial reefs and aquaculture farms, with the data painstakingly sourced from the individual sectors of these different industries.

The result is what the scientists call the first map of human development in the world’s oceans, revealing how much of the marine environment had been altered by our activity.

According to the team, a total of around 30,000 sq km (11,600 sq mi) has been modified by human construction, which amounts to 0.008 percent of the entire ocean.

But as lead author Dr Ana Bugnot explains, the effects are a lot more far-reaching than that.

“The effects of built structures extend beyond their direct physical footprint,” she tells New Atlas.

“Marine construction can modify surrounding environments by changing ecological and sediment characteristics, water quality and hydrodynamics, as well as noise and electromagnetic fields.”

Dr Bugnot and her team drew on existing data and research to quantify the impact of these types of flow-on effects, and found that the footprint of these structures is actually two million square kilometers (770,200 sq mi), more than 0.5 percent of the ocean as a whole.

Among the more surprising revelations from the analysis were that 40 percent of the physical footprint of all structures can be attributed to aquaculture farms in China, and that noise pollution can carry up to 20 km (12 mi) from commercial ports.

While evidence of manmade alterations to the oceans dates back thousands of years, to the early construction of ports and breakwaters to protect low-lying coasts, the phenomenon began to accelerate around the mid-point of the 20th century, according to the team.

This construction mostly takes place in coastal areas, and to better understand this trend the team cast an eye to the future, assessing data on planned projects and assuming a business-as-usual approach.

"The numbers are alarming," Dr Bugnot says.

"For example, infrastructure for power and aquaculture, including cables and tunnels, is projected to increase by 50 to 70 percent by 2028.

Yet this is an underestimate: there is a dearth of information on ocean development, due to poor regulation of this in many parts of the world.”

The team hopes the study can draw attention to the importance of conserving marine environments, and that the findings can provide a starting point for further investigation and tools to track of these types of ocean construction projects on an ongoing basis.

“The estimates of marine construction obtained are substantial and serve to highlight the urgent concern and need for the management of marine environments,” says Dr Bugnot.

“We hope these estimates will trigger national and international initiatives and boost global efforts for integrated marine spatial planning.

To achieve this, it is important to rump up efforts for detailed mapping of historical and existing marine habitats and ocean construction.”

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Ocean Data for All: Why we need to break down barriers for the global sharing of ocean data

From Institute of Oceanography, National Taiwan University by Linwood Pendleton

The ocean works at a global scale.

To understand changes at a global scale, we need to ensure that ocean data are readily available in global data sets.

Unfortunately, ocean data are often siloed – trapped in national databases, on laptops, and in logbooks.

How does Ocean Data For All solve the problem?

We have only one ocean

The Ocean supplies the air we breathe, regulates the climate, feeds billions of people, and supports an important and growing global economy.

There are 150 ocean countries, 83 of which are more ocean than land.

To manage this ocean, we need a robust global set of ocean data from all of this ocean.

Ocean data are used to monitor oceanic and climatic change, to assess fisheries health, to track biodiversity, and to alert the public of hazards like harmful algal blooms.

These data also are used to create models to warn of storms and tsunamis, changes in fish abundance, and to plan for ocean change.

Ocean data and the science needed to produce them are essential to plan for sustainable development and are so important that the United Nations declared that the next decade will be the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

“The ocean works at a global scale. To understand changes at a global scale, we need to ensure that ocean data are readily available in global data sets. Artificial intelligence and machine learning methods are needed to understand and predict global ocean processes. Yet, AI can only be applied if the data are all in one place, organized and easy to read by computers.”

Unfortunately, ocean data are often siloed – trapped in national databases, on laptops, and in logbooks.

Even when data are shared online, it is often difficult to find and access these online databases.

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission has long been a home to such a global database of ocean data.

Stewarded by the International Ocean Data and Information Exchange, the World Ocean Database (WOD) and the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) have provided global sources of ocean data.

But, even with the backing of most of the world’s ocean countries, the WOD and OBIS still do not fully reflect ocean conditions around the planet.

Head of northern right whale with NOAA Ship DELAWARE II in background.

Head of northern right whale with NOAA Ship DELAWARE II in background. We don’t have the global data we need to manage the ocean

Today, fewer than 30 countries regularly contribute to the World Ocean Database – the oldest and most global set of essential ocean data (compared to more than 60 countries just 2 decades prior).

In 2018, the World Ocean Database had fewer than one data station per 1000 km2 for nearly three-quarters of the world’s coastal waters (the blue in the first map).

Without these data, global ocean and climate models do not account for conditions in many of the world’s sovereign ocean areas and we are unable to assess the impacts of climate change or progress towards certain Sustainable Development Goals.

Data regarding biodiversity are similarly lacking (second map).

We have a higher density of biodiversity data for Antarctic waters than for nearly all of the Global South.

“Barriers to data sharing must be removed.

Many countries have ocean data, but do not share these data.

In some cases, lack of human, technical, and financial capacity may limit data sharing.

Formal policies and informal practices may also slow data flow.

National security interests, real or perceived, may prevent ocean data sharing.

Of course, in some places there are simply no data to share.”

With more than 120 ocean countries failing to regularly share ocean data and virtually no shared data for the vast majority of ocean countries, steps need to be taken to fill the gaps in our understanding of ocean conditions and change.

Without these data, it will be difficult to achieve sustainable development goals and a sustainable blue economy.

To begin to address these hurdles to ocean data sharing, a unique partnership – Ocean Data For All - has been created by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, the World Economic Forum’s Future of a Connected Planet Program, and the Centre for the 4th Industrial Revolution – Ocean.

These partners are working to analyze patterns of ocean data sharing to understand whether, when, and where increased sharing of ocean data could be achieved through technological, political, legal, cultural, financial, or other means.

While the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development is focused on increasing the capacity to create new data through science, the Ocean Data for All project seeks to make sure that these new data and knowledge are shared in ways that are global and open – allowing scientists, planners, and industries around the world to benefit from a more global understanding of ocean processes and conditions.

To go from analysis to action, however, will require the involvement of leaders in government, industry, technology, and philanthropy all of whom are needed to supply the intellectual and financial resources to break down these barriers.

Through opportunities like Taiwan’s Ocean Challenge event in Kaohsiung, I am reaching out to students, governments, and leaders in the technology and business to enlist their help in this global effort.

We all have a role to play in ocean science.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Great white sharks at times enter San Francisco…

From MercuryNews by Paul Rogers

Windsurfers, fishing boats and cargo ships aren’t the only traffic in San Francisco Bay.

Great white sharks are there sometimes, too.

In what is believed to be the first scientific confirmation of white sharks in San Francisco Bay, researchers from Stanford University, the University of California-Davis and other organizations put satellite and acoustic tags on 179 white sharks in Northern California waters from 2000 to 2008.

They found that most of the sharks migrated thousands of miles every year, from California to as far away as Hawaii, and five swam underneath the Golden Gate Bridge in 2007 and 2008 and into bay waters.

It isn’t known exactly where the sharks went once in the bay, only that their acoustic tags were detected by receivers anchored to the bay floor between the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz Island.

“All we know so far is that they are poking their heads across the Golden Gate,” said Barbara Block, a professor of biology at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove who helped lead the tagging study.

“I doubt they are coming in very far because they are salt water animals.”

There are nearly a dozen species of sharks known to live in the bay, including leopard, sevengill and other, mostly docile bottom-dwelling varieties.

Researchers have wondered for years whether great whites — apex ocean predators that can reach 15 feet long or more and weigh 4,000 pounds — are there too.

But there have been no documented cases of white sharks ever attacking seals, sea lions or other animals in the bay, let alone people, said John McCosker, a veteran shark researcher at the California Academy of Sciences.

“The conditions aren’t good. The water isn’t clear,” McCosker said.

“You can’t see your dinner in San Francisco Bay.”

Contrary to sensationalism from Hollywood films, attacks by white sharks are rare.

Far more people die each year from dog bites or hitting deer with cars.

Since 1952, there have been 99 white shark attacks in all of California, according to McCosker’s records, and 10 fatalities.

Most were surfers or divers in places where elephant seals and sea lions — some of the white sharks’ primary prey — are frequent.

The only documented white shark fatality in San Francisco came on May 7, 1959, when Albert Kogler Jr., 18, died while swimming in less than 15 feet of water after he was attacked off Baker Beach, about one mile west of the Golden Gate Bridge.

The president of one prominent swimming club said Tuesday that the news that white sharks occasionally come into the bay is interesting, but not that surprising.

“The conventional wisdom has always been that they don’t come beyond the bridge.

I don’t think I ever believed it,” said Ken Coren, president of the Dolphin Club, in San Francisco.

Coren, an open water swimmer for more than 25 years, said bay swimmers think about sharks, but know the risk is very low.

He said he doesn’t think the news will scare many swimmers from their usual routines.

“The most deadly thing we face are propellers,” he said.

The latest research was published today in the “Proceedings of the Royal Society B,” which is the biological research journal of Great Britain’s national academy of sciences, the Royal Society.

In it, scientists used high-tech acoustic tags to find that white sharks display amazingly precise migration patterns.

They are most numerous off Northern and Central California between September and November, and almost all gone from April to July.

While in the area, white sharks congregate at four key sites, each of which supports large colonies of seals and sea lions: Southeast Farallon Island, Tomales Point, Año Nuevo Island, and Point Reyes National Seashore.

When the sharks leave each spring, satellite tags show, they swim as far as Midway Island and Hawaii, but also mass in large numbers in an area of open ocean between Hawaii and Baja California known as “the White Shark Café,” where researchers believe they may mate and forage for food.

In the fall, they return back to the same places they left a year earlier.

“We tend to think of white sharks as animals that wander oceans aimlessly,” said Block.

“What we’re learning is how selective a predator they are.

The go up to 4,000 miles in a trip and come back to within half a mile of where they left.”

It isn’t known how white sharks navigate, although their ability to sense electromagnetic energy in the ocean may play a role.

The researchers also found by taking DNA samples that white sharks in Northern California are a genetically distinct population from other groups of white sharks in the world, such as Australia and South Africa, and that they may have descended from Australian great whites 200,000 years ago.

The five sharks that came into San Francisco Bay represent less than 1 percent of the nearly 64,000 detections researchers picked up along the California coast from acoustic tags.

Some details are known about the bay visits, however.

One shark was detected one time inside the Golden Gate Bridge in December 2008; a second shark was detected one time, in April 2008; a third shark was detected four times, between November 2007 and November 2008; and a fifth shark was detected three times, in August and September 2007.

Salvador Jorgensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford who is the lead author on the study, said that having tagging data could in the future help better inform the public around the world about white shark behavior, reducing the risk of encounters.

It may also help researchers one day get a population estimate for great whites, whose numbers are believed to be on the decline.

In addition to Jorgensen and Block, the research team included Carol Reeb and Christopher Perle of Stanford; Peter Klimley and Taylor Chapple of UC-Davis; Scot Anderson of Point Reyes National Seashore; Adam Brown of PRBO Conservation Science; and Sean Van Sommeran and Callaghan Fritz-Cope of the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation.

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

‘They just left us’: Greece is accused of setting migrants adrift at sea

From NYTimes by Carlotta Gall

Frustrated by more than a year of picking up people they say Greece has illegally pushed out, Turkish officials invited journalists to witness rescues firsthand.

ABOARD A TURKISH COAST GUARD VESSEL — Wet and shaken, women and children were pulled aboard the Turkish patrol boat first, then the men and more children.

A 7-year-old girl in striped leggings, Heliah Nazari, shivered uncontrollably as she was set down on the deck. An older woman retched into a plastic bag.

They were two of 20 asylum seekers from Afghanistan who had been drifting in the dark, abandoned in rudderless rafts for four hours before the Turkish Coast Guard reached them.

Just hours earlier they had been resting in a forest on the Greek island of Lesbos when they were caught by Greek police officers who confiscated their documents, money and cellphones and ferried them out to sea.

“They kicked us all, with their feet, even the children, women, men and everyone,” said Ashraf Salih, 21, recounting their story.

The Turkish Coast Guard officials described it as a clear case — rarely witnessed by journalists — of the illegal pushbacks that have now become a regular feature of the dangerous game of cat and mouse between the two countries over thousands of migrants who continue to attempt the sea crossing from Turkey to the Greek islands as a way into Europe.

Since a mutual agreement broke down last year, Turkey and Greece have been at loggerheads over how to deal with the continuing flow of migrants along one of the most frequented routes used since the mass movement boomed in 2015.

Then, one million migrants, mostly Syrians fleeing the war in their country, led the surge into Europe. The flow is much reduced — 40,000 have arrived by sea into Europe so far this year — but it is now dominated by Afghans, raising fears that the escalating conflict there and the American withdrawal of troops could bring larger numbers.

For more than a year, Turkey has turned a blind eye to the migrants, allowing them to try the sea crossing to Greece.

Increasingly, Greece is even removing asylum seekers who have reached its islands, forcing them into life rafts and towing them into Turkish waters, as the compassion many Greeks had shown during earlier waves of migration has given way to anger and exhaustion.

The tactic of so-called pushbacks has been roundly denounced by refugee organizations and European officials as a violation of international law and of fundamental European values.

“It is obvious they were pushed back,” said Senior Lt. Cmdr. Sadun Ozdemir, the Northern Aegean group commander in the Turkish Coast Guard, after his crew rescued a group of Afghans in the Aegean. Credit...Ivor Prickett for The New York Times

“It is obvious they were pushed back,” said Senior Lt. Cmdr. Sadun Ozdemir, the Northern Aegean group commander in the Turkish Coast Guard, after his crew rescued a group of Afghans in the Aegean. Credit...Ivor Prickett for The New York Times“Numerous cases have been investigated, including by the European Union,” Notis Mitarachi, minister for migration and asylum in Greece, said last week, “and reports have found no evidence of any breach of E.U. fundamental rights.”

Philippe Leclerc, head of the United Nations refugee agency in Turkey, said his office had presented evidence, including “accounts of violence and family separations” to the Greek ombudsman, requesting the cases be investigated, without result.

The two countries are at an impasse, with Turkey demanding that Greece end the pushbacks first, and Greece demanding that Turkey first take back 1,400 migrants whose asylum requests have been rejected, Mr. Leclerc said.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey has been widely accused of precipitating the crisis, when in February last year he announced he was opening his country’s borders for migrants to travel to Europe.

Turkish officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not permitted to speak to the news media, said the step was taken to draw world attention to Turkey’s own burden in hosting some four million asylum seekers from other nations’ wars — more than 3.6 million Syrians, along with 400,000 other people from Afghanistan, Asia and the Middle East.

But the action was interpreted in Greece as a kind of blackmail to extort money and other concessions from the European Union on a range of issues.

It led to clashes between migrants and Greek border guards on the Turkish-Greek border and caused the conservative Greek government to adopt aggressive new measures against migrants, including the pushbacks.

Greece has struggled to handle the influx of more than 100,000 asylum cases and overcrowded refugee camps on its islands while other European countries have done little to share the burden.

But Turkish officials stress that the numbers Greece is handling is nothing compared with the scale of the strain on Turkey.

Frustrated after more than a year of picking up thousands of migrants left by their Greek counterparts, the Turkish Coast Guard invited journalists recently on a patrol boat to witness what they said were the Greek violations.

“It is obvious they were pushed back,” Senior Lt. Cmdr. Sadun Ozdemir, the Northern Aegean group commander of the Turkish Coast Guard, said after his crew had rescued the 20 Afghans.

He said the Greek vessel had probably towed the rafts deep into Turkish territorial waters before cutting them adrift, which he said was an additional violation.

One raft was overloaded and the thin bottom leaking, he said.

As often happens, the Turkish crew received an email from their Greek counterparts that migrants were drifting in the area — a seeming effort by the Greeks to mitigate loss of life but something the Turks say is an implicit sign of Greek culpability.

Tommy Olsen, who runs the Aegean Boat Report, a Norwegian nonprofit that tracks arrivals of migrants on the Greek islands, confirmed through photographs and electronic data that members of the group had been on the island of Lesbos that day.

A local photographer also took pictures of some of them in front of a Greek church, a landmark on the south of the island.

The pushbacks also damage relations between the Greek and Turkish Coast Guards and interfere with work against drug and people trafficking, Commander Ozdemir said.

Commercial ships as well as navy and coast guard vessels pass through the northern Aegean and could easily hit the small rafts and boats, which have no lights or means of navigation, he added.

“This thing we call ‘pushback’ in English is a very innocent expression,” he said. But the action was anything but, he said, hoping to convey “how desperate the situation is.”

Interviews with migrants rescued by the Turkish Coast Guard in several incidents over the course of four nights revealed the scale of Greek violations and the growing desperation of migrants.

One group of 18 people, from Africa and the Middle East, were rescued after their engine broke down.

Muhammad Nasir, 29, said he had fled the war in Yemen after his father was killed. He was trying to join his uncle in Britain.

“For three months, I have been trying,” he said, his voice cracking. “I feel disappointed. I cannot stay in Turkey, I do not have a job and my family are waiting for me to help them.”

An Afghan teenager with an injured leg, Reyhan Ahmedi, 16, was picked up after six hours at sea alone after being expelled by Greece.

“I thought I should take myself away from Afghanistan and find a better future for myself,” he said.

The Aegean, near Cunda, Turkey. Some 40,000 migrants have arrived by sea into Europe so far this year, mostly Afghans.

The Aegean, near Cunda, Turkey. Some 40,000 migrants have arrived by sea into Europe so far this year, mostly Afghans.- GeoGarage blog :Revealed: 2,000 refugee deaths linked to ... / Banksy funds refugee rescue boat operating ... / The mission to raise the anchor from a ... / 'I'll die with no regrets': risking their lives in ... / The risks to migrants of crossing the English ... / What rules apply to migrants rescued at sea? / A perilous journey: How many asylum ... / Migrants can't be left to die in the seas of ... / Mediterranean migrant deaths reach record ... / Mediterranean Sea Rescue - GeoGarage blog / The millionaires who rescue people at sea / SAR crisis in the Mediterranean ... / A wintry sea seems a safer bet than life at ... / Lampedusa, the Italian Island thousands are ...

- EU Observer : NGO sea-rescue mission exposes reality of EU 'values'

- UN: Migrant deaths on sea routes to Europe more than double

- IOM/UN : Deaths on Maritime Migration Routes to Europe Soar in First Half of 2021: IOM Brief

Monday, July 19, 2021

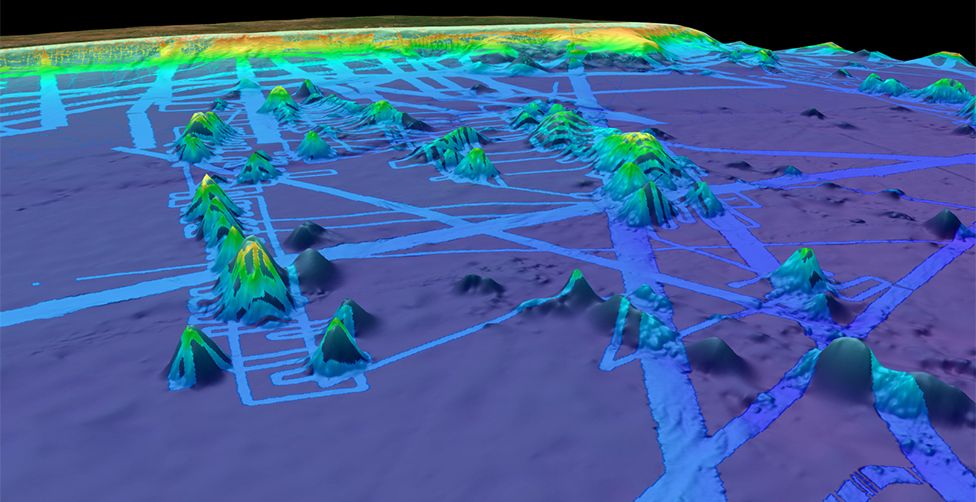

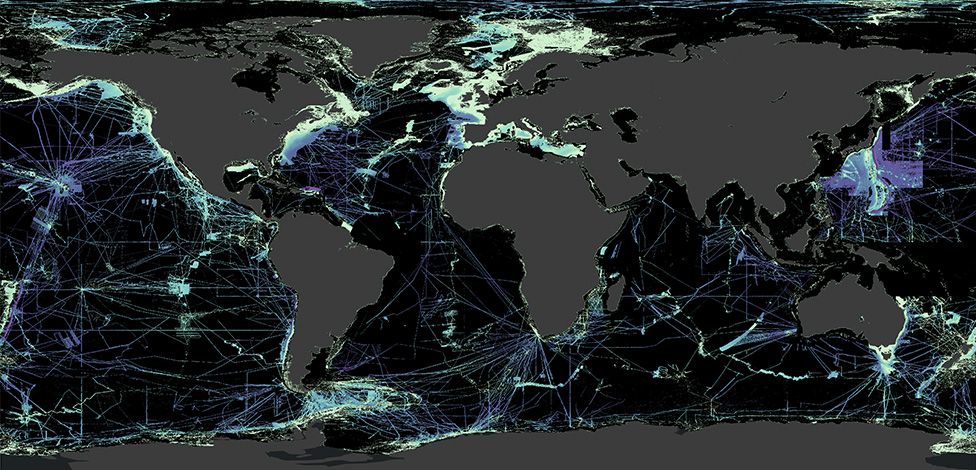

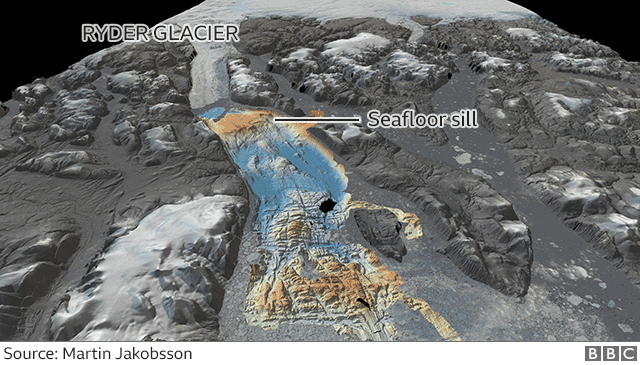

Mapping quest edges past 20% of global ocean floor

image

copyright GEBCO / Vicki Ferrini

image

copyright GEBCO / Vicki FerriniModern measurements of the depth and shape of the seabed now encompass 20.6% of the total area under water.

The extra 1.6% is an expanse of ocean bottom that equated to about half the size of the United States.

The progress update on Seabed 2030 is released on World Hydrography Day.

image copyright Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Projecti

image copyright Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 ProjectiBut the GEBCO initiative is confident the data deficit can be closed this decade with a concerted global effort.

"If you're going to sea for whatever reason, switch on your echosounder.

Even if you're just a yachtsman, a recreational sailor - then low-tech data-logging equipment is only a few hundred dollars, with the price coming down all the time.

When Seabed 2030 was launched in 2017, only 6% of the oceans had been mapped to modern standards.

So, it is possible to make swift and meaningful gains.

For example, a big jump in coverage would be achieved if all governments, companies, and research institutions released their embargoed data.

There's no estimate for how much bathymetry (depth data) is hidden away on private web servers, but the volume may be very considerable indeed.

Those organisations holding such information are being urged to think of the global good and to hand over, at the very least, de-resolved versions of their proprietary maps.

Seabed 2030 is not seeking 5m resolution of the entire floor (close to something we already have of the Moon's surface).

One depth sounding in a 100m grid square down to 1,500m will suffice; even less in much deeper waters.

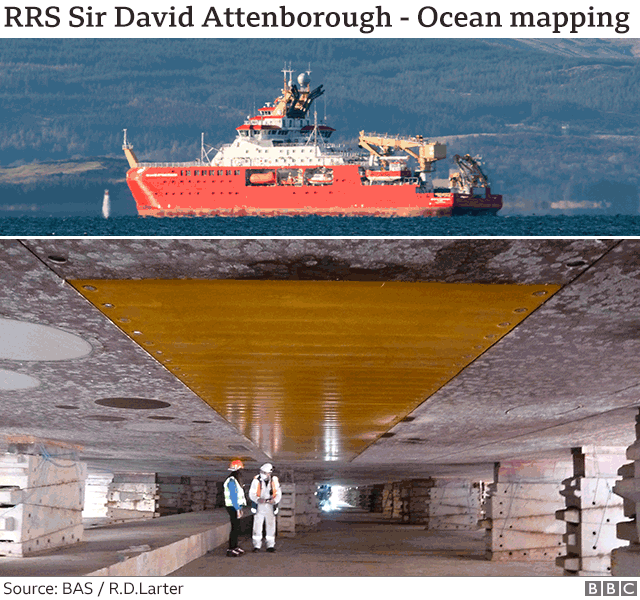

The UK's new polar ship, the RRS Sir David Attenborough, is equipped to map millions of square km of ocean bottom over its career.

The above image shows the ship's hull in dry dock.

The yellow rectangle in the centre is a cover made of a synthetic material over the 8m-long array of transmit transducers for the deep-water multibeam echosounding system.

The receive array is at right angles to this, just behind the people in the photo, but difficult to see because it is covered by a material that has much less contrast with the rest of the hull.

Transducers for several other systems are also visible.

The yellow square next to the individuals' heads is the transmit transducer for the acoustic sub-bottom profiling system, which provides a profile showing the layers in the upper few metres of sediment.

This is unfortunate because it's the science expeditions that will often visit those parts of the oceans where few other ships venture - into the Southern Ocean, for example.

That said, there've been some notable contributions of late from the research sector.

One of the most significant has come from the DSSV Pressure Drop, a ship funded by the Texan billionaire and adventurer Victor Vescovo.

His expeditions to the very deepest parts of Earth's oceans mapped an area equivalent to the size of France in just 10 months (an area the size of Finland within this had never been seen before)

Better seafloor maps are needed for a host of reasons.

They are essential for navigation, of course, and for laying underwater cables and pipelines.

They are also important for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around the underwater mountains that wildlife tends to congregate.

Each seamount is a biodiversity hotspot.

In addition, the rugged seafloor influences the behaviour of ocean currents and the vertical mixing of water.

This is information required to improve the models that forecast future climate change - because it is the oceans that play a pivotal role in moving heat around the planet.

If Seabed 2030 is to meet the end-of-decade target, it will have to leverage the emergence of robotic ships and boats.

Fugro, one of the world's leading marine geophysical survey companies, is building a fleet of USVs based on the Ocean X-Prize-winning SeaKit roboboat.

Fugro has two such boats surveying and inspecting oil-and-gas, wind farm, and power installations - in European waters and off Western Australia.

Together, they are known as the Blue Essence fleet.

These boats will even deploy and recover robotic subs.

"These drone-type, or uncrewed-type, solutions will make it easier to gather more data.

They can do a lot more work in the same amount of time," said Ivar de Josselin de Jong, Fugro's solution director for remote inspection.

"Technology is moving very fast. It's unbelievable what we do now compared with what we did 10 years ago.

"We can operate a USV in Australia from our remote operations centre in Aberdeen.

"We've got 26 crewed vessels at the moment and we want to gradually replace them - partially at least.

Where we don't need 'hands' in an offshore environment, we will move to uncrewed solutions, to reduce the health and safety exposure and to reduce carbon footprints," he told BBC News.

To mark World Hydrography Day, The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project has entered a technical cooperation agreement with the UK Hydrographic Office and Teledyne CARIS, a leading developer of marine mapping software.

Building the definitive map of Earth's ocean floor means collating colossal volumes of data.

The new tie-up will see a new artificial intelligence tool being used to clean bathymetric data of "noise", making it easier to pull out reliable depth soundings.