Its best hope may lie in mangrove

trees.

"Wake up! The sea is taking it all away, it's taking it all away!" were the first cries Claudia Ramón heard that night, when a fierce wave lashed her town.

"It was my cousin who warned me, and I ran to take out my personal things.

If she hadn't grabbed my arm tightly, the wave would have rolled me over too," says the young woman standing on the rubble in the sand.

Where the family bodega used to stand there's now only a huge sinkhole.

In the background there's the squawking of seagulls and a calm, silent horizon, oblivious to the roaring wind that mercilessly lashed the landscape of Las Barrancas, Mexico, in the early morning of October 2, 2022.

It was not the first time that a storm had stolen houses and a piece of beach from this fishing village situated at the foot of a ravine in the municipality of Alvarado, in the state of Veracruz.

It's a town of no more than 300 inhabitants, and it’s population has decreased steadily over the past decade.

This is due in part to the lack of employment opportunities that sends young people packing, but mostly because the sea increasingly threatens to carry away the small buildings and leave families without shelter.

“We have been suffering the onslaught of the sea for a long time.

It started 14 years ago, but increased 10 years ago,” says Nancy Otsoa as she walks along the shore, an increasingly narrow line of the beach.

The erosion was accelerated in 2021 by the onslaught of hurricanes and tropical storms.

"That night, the last night a storm hit us so hard, the water came right up to the main street," she recalls.

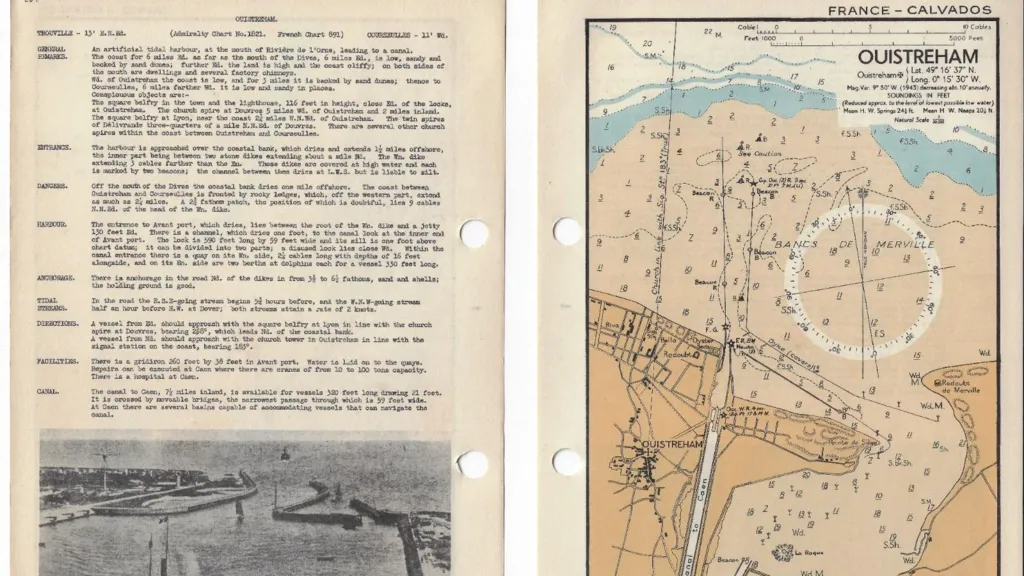

Ruins of one of the houses that the sea took away in Las Barrancas, in Veracruz, Mexico.

Photograph: Seila Montes

Around her are mounds of sandbags and tires, placed there by locals to mitigate the impact of the storm surge.

"But it's no use, as soon as the winds come, another piece of coast is ripped off," she says.

Dozens of lifeless starfish are piled up nearby, extracted from the salt water by the north wind and abandoned on this piece of land.

As of 2021, 71.7 kilometers of beaches in Alvarado had coastal erosion.

More ruins in Las Barrancas.

Photograph: Seila Montes

10 Years Fighting the Sea

"The first town that was affected was Matalauva.

Zapote followed, and then we began to lose a lot of beach," says Otsoa, who heads the Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Barranqueña del Golfo.

Founded 35 years ago, the consortium is made up of 41 members: 24 men and 17 women who started a business to sell canned goods from the fish they catch at sea.

"We use everything from the bonito and other species to make our products, such as the ceviche pulp for minilla, a typical local dish," explains Otsoa, who is leading the fight to keep her community from disappearing from the map.

It is a battle against the maneuvers of megaprojects, the ravages of climate change, environmental degradation in the region, and the abandonment of a village that is disappearing with the onslaught of the sea.

"Not so long ago it was common to see children playing in the waves while the women fished on the shore," she recalls.

Those days are long over.

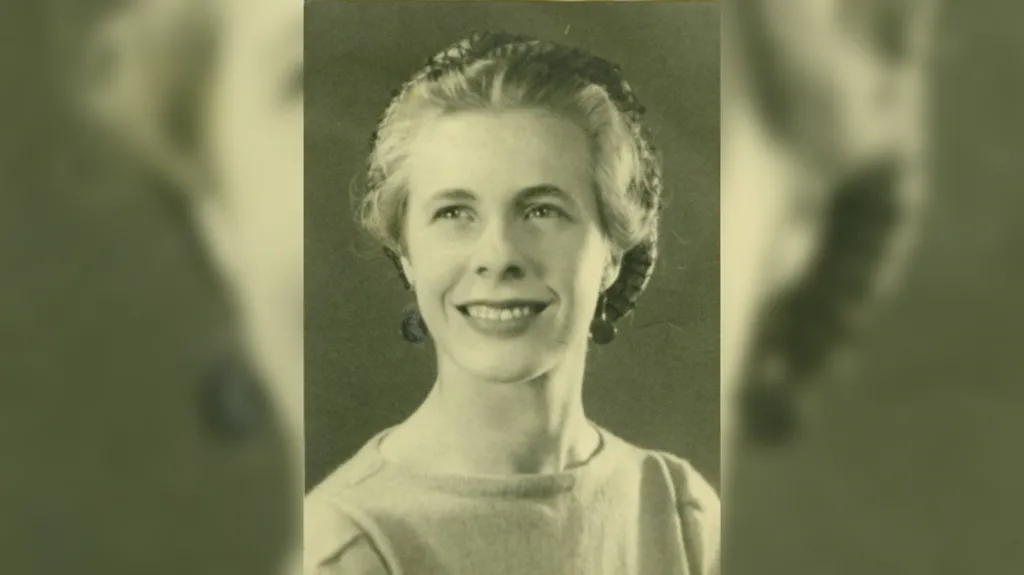

Nancy Otsoa with her grandmother Florencia “Pola” Hernández, 81, in Las Barrancas, Mexico.

Photograph: Seila Montes

"That's why my husband hardly ever goes out anymore.

You have to go far out to sea," says Florencia Hernandez, 81, grandmother of Otsoa and Ramón, known locally as Pola.

In a wheelchair surrounded by memories—black and white portraits, lead hooks, the fishing line she holds in her hands—she is the longest-lived witness of the transformation that her land has undergone.

She learned the fishing trade in her youth.

"My father taught me.

Like my grandfather, he was a fisherman.

He had a little wooden boat, and he took me when I was a child," says Hernandez while showing a photo album.

"Later, I fished with my brother Salvador.

I was the one who grabbed the motor.

We would go out at night.

When I got married, I accompanied my husband.

I would get up very early in the morning, leave the clothes washed and laid out for when we returned from the day's work.

In a short time, we would fill baskets with fish that we would sell in the afternoon," she says.

An abandoned boat in the fishing community of Las Barrancas, Mexico.

Photograph: Seila Montes

Hernandez and her husband raised their children with what they earned from the sea.

"The sea that has given me everything and now takes everything away," she says with a broken voice.

In Las Barrancas they live every day with the fear of the arrival of a hurricane like Roxanne, which landed in 1995.

"I was only 8 years old but I remember it very well. That one hit very hard. It took a lot of houses," says Ramón.

Climate Change and Poorly Planned ProjectsBetween the storm surges, the sea level continues to gradually rise.

In the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, that increase is about three times faster than the global average, according to

a 2023 study published in Nature.

"This could be due to the loss of important habitats, such as seagrasses and reefs, natural barriers that protect the coast," says Patricia Moreno-Casasola, a biologist at the Institute of Ecology.

“Here it's already taken 100 meters of beach,” says Otsoa.

"The impact has not only been environmental and on fishing, on which we live, but it has also had a great social impact.

The beach was our means of communication with the other neighboring communities," explains the fisherwoman.

The tourism that her town used to attract has also fallen off.

“My mother had a little food stand by the beach that was crowded at Easter, a business that sold snacks.

We lived on that income almost all year round,” Ramón says.

Even horse races were organized there on the beach."

Claudia Ramón in Las Barrancas, Veracruz, facing the ravages of rising sea levels.

Photograph: Seila Montes

"We already know that climate change is behind this situation.

But also human action, the expansion of the hotel zone, poorly founded works carried out without impact studies," says Otsoa.

The activist devoted years of research to better understand how the destruction of ecosystems and climate change are affecting coastal territories.

Otsoa was so eager to learn that she enrolled in an online university and spends hours of her day talking to experts to help her find solutions.

"In this community it is the women who move everything," says Moreno-Casasola, one of Mexico's leading experts in sustainable development.

She says that the erasure of beaches in the region is due to different factors, “such as the loss of sediments that used to be carried by rivers to the sea or the melting of glaciers, which raises sea levels.

But, above all, due to the expansion works carried out in the port of Veracruz and the construction of breakwaters in the northern area of Alvarado,” she says.

Ruins of one of the houses that the sea took away in Las Barrancas.

Photograph: Seila Montes

Projects carried out by the Ministry of the Navy and the networks of corruption in the region have provoked, little by little, the acceleration of the erosion of the Veracruz coast.

"We are more and more isolated.

The streets are used to store the boats; we no longer have a place to keep them.

Many residents have sold their boats and we have to look for other alternatives to survive.

Many people leave because they have lost their homes," Otsoa explains.

Years ago she also decided to leave the place where she grew up to find luck in the United States.

"We made it there, but the border patrol caught us and sent us back in a truck.

It was our whole family, my mom, my brother, my husband, my aunt, a cousin.

They didn't want us there because destiny had another future in store for us," says the fisherwoman, who no longer trusts anything.

“Not even the sea. We are already very afraid of it because it is getting stronger and stronger.”

No Response From the Government

"There is no mitigation plan from the authorities," she says.

The woman has been requesting support from different officials for more than a decade.

"I have already presented evidence with all the government agencies, even to the president, who came and promised to help us.

But time goes by and time goes by and we don't receive any response.

We are alone, abandoned," she says.

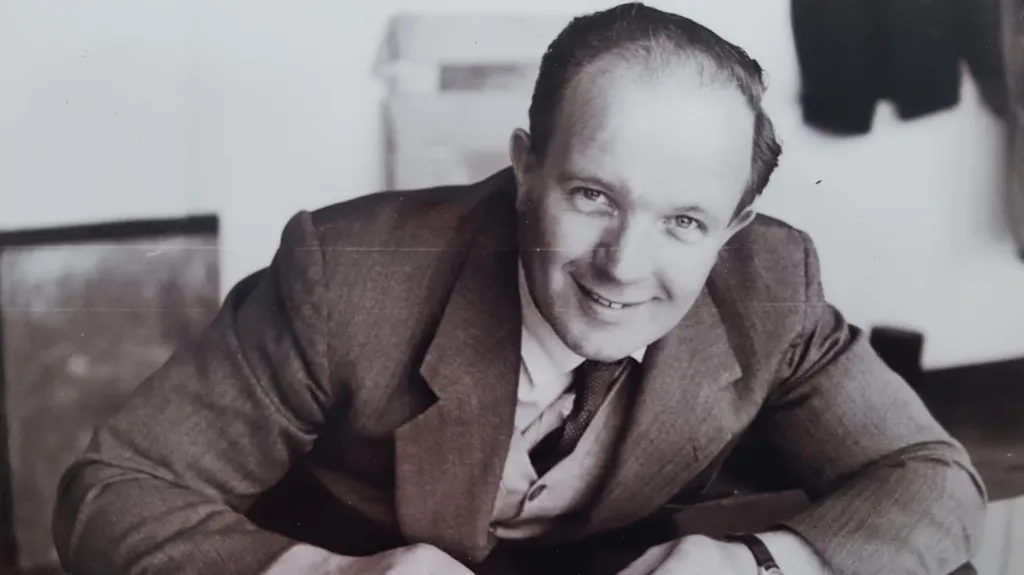

Fishermen fixing a motor in Barrancas, Mexico.

Fishing is the main economic activity in the town, increasingly affected by climate change and environmental degradation.

Photograph: Seila Montes

Before better understanding the implications of the disaster looming over her community, Otsoa hoped for a breakwater that had been promised years ago by Javier Duarte de Ochoa, the state governor.

(Ochoa, a controversial leader accused of several corruption crimes, was sentenced to prison in 2017.) The breakwater he intended to erect was supposed to protect the coast and divert currents, like the one he inaugurated in 2014 in the neighboring community of Matalauva.

Its installation helped Matalauva and the neighboring community of Zapote recover part of their beaches.

The Las Barrancas breakwater never materialized.

"They managed to bring back tourism, which had a very strong economic benefit.

If they can benefit, why can't we?" Otsoa asked herself at the time.

But while the construction of the breakwater in the neighboring community brought immediate benefits, Otsoa no longer wants one.

"The long-term effects are unknown and, after much research, I know that this is not the solution," she says.

"Installing a barrier over the beach dramatically changes the dynamics of the currents.

Putting a spur provides a short-term solution in a specific location, but it moves the problem elsewhere.

There are already many studies on the consequences of this approach," says Jacobo Santander, a biologist with the Interdisciplinary Collective of Applied Science and Environmental Law who came to the community four years ago to study the complex phenomenon and help this town defend itself against the rising sea and the pounding waves.

Ruins of one of the houses that the sea took away in Las Barrancas, Mexico.

The destruction of ecosystems and climate change are affecting coastal territories.

Photograph: Seila Montes

“The disappearance of beaches in this region stems from a multifactorial problem.

On the one hand, there are the mega works executed without sensible planning, such as the port expansion of Veracruz or the artificial barriers in the middle of the sea that the government developed.

Because of the distance on the map they appear as distant points, so they may seem to be isolated events.

However, they are connected, and the effects have repercussions in this area.

On the other hand, the deterioration of ecosystems is a fundamental part of sediment erosion,” says the Santander.

Moreno-Casasasola agrees with that hypothesis, and has a potential solution.

“Regardless of the rise of the sea due to climate change, there is a serious problem of lack of sediment.

That is why we must recover the mangrove system, which provides the substrate that acts as a barrier against tidal waves.”

Saving a Mangrove to Protect the Beach

To face the complex situation that threatens the Barrancas, it would be more productive, scientists say, to work on the natural areas in the territory than to build a breakwater in the sea.

That's why they're developing a plan for the recovery of the ecosystems that includes its inhabitants.

A major part of that plan is the Salao, as this community calls its mangrove swamp.

Home to more than 80 species of fauna and flora, up to three species of mangrove and about 30 bird species find refuge here.

“We are betting on the rehabilitation of habitats to recover coastal protection.

So that nature returns sediment to the coast.

The idea is to recover the balance that existed before, to return the natural flow to the mangrove and its exchange of sediment with the beach.

Because in spite of the pressure of pollution we can still do something, there is life here, there are species, flora, a lot of fauna,” Ramón says with enthusiasm in his voice, proud that the work has already had a visible impact.

"There is an incredible capacity for restoration. We put the mangrove seed on the shore of the beach and it's already sprouting, it has stuck and is reproducing!"

Claudia Ramón in the Las Barrancas mangrove swamp.

Photograph: Seila Montes

For Las Barrancas to return to its former landscapes, "awareness is also key.

That is why we carry out environmental education campaigns," says Santander.

Despite the cleanup days, much of the mangrove area is still covered with debris.

"Some of that arrives from the sea and some of it is directly thrown away, especially plastic.

We insist a lot to the neighbors that they have to recycle and stop throwing waste.

And little by little we are succeeding.

The burning of garbage is another problem.

We don't have a public cleaning service here," says Otsoa as she strolls among the old mangrove roots and sorts through the containers, plastics of all colors and shapes, fishing nets, pieces of tires, many bags, cans of soft drinks … plastics, plastics, and more plastics.

"We would also like to recover the waterfall," Ramón says.

The one where they used to bathe.

"It had a tremendous stream and gave very good water. But the hill began to collapse, roads were opened, construction work was done and, over the years, the flow deteriorated," she says.

“If we have learned anything over the years, it is that to be better off we must take care of our environment,” Otsoa says.

Ruins of one of the houses that the sea took away in Las Barrancas, Mexico.

Photograph: Seila Montes

The village also plans to create fishing refuges, an idea that biologist Santander suggested.

"We started to work on the initiative, to let fishing rest for a while.

We want to organize ourselves with the rest of the fishermen of the coastline we share and designate these refuge zones.

Only together can we define them, decide how long fishing should stop, and see how the species repopulate little by little," Otsoa says.

Under her arm she carries a folder with all the documentation she has been compiling: files on the erasure of territory, rising sea levels, letters sent to the authorities asking for support, requests for them to take action, photographs and videos that show how Las Barrancas used to be and how it has been reshaped.

“When President López Obrador came to Veracruz, we approached him, part of the community, and gave him the letter.

He promised to take action, but he never did.

And we don't know what to do to make officials listen to us.

We are afraid that the help will arrive when it's too late.

We don't want it to happen to us like it did to the people of Tabasco,” says Otsoa, referring to El Bosque, the town located in the municipality of Centla that was completely swallowed by the sea.

After years of suffering the ravages of tides and surges, in February of this year all of its inhabitants had to be evicted.

"That's what we don't want to happen to us," says Pola.

As her granddaughter Otsoa explains, a relocation “would be devastating because it would force us to change our way of life.

What we have here is a heritage achieved through hard work.

We were born here, and we have always lived here.

Belonging to Las Barrancas is part of our identity.

That is why we cannot allow ourselves to lose our land.

That is why we continue to fight and do the work that the government does not do; we work so that the balance of nature returns.

And so that they listen to us before it's too late.

Before only the name of this community remains as a memory, and so that future generations don't have to say that their town was destroyed by the sea.”

Links :

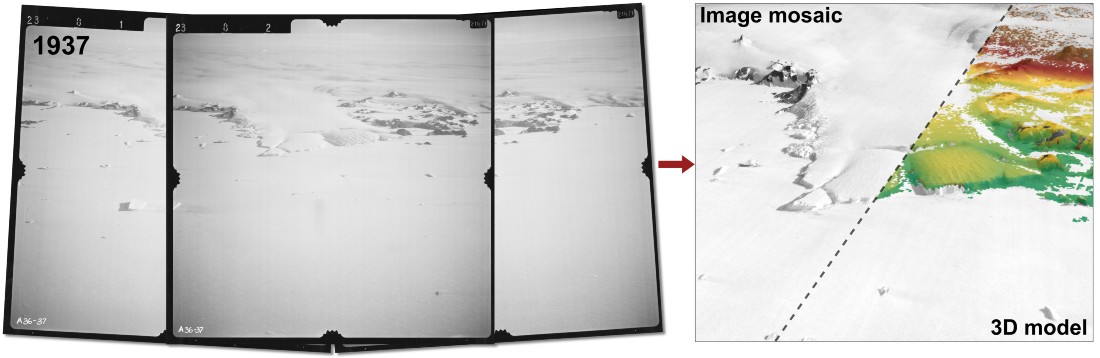

From aerial images to 3D models.

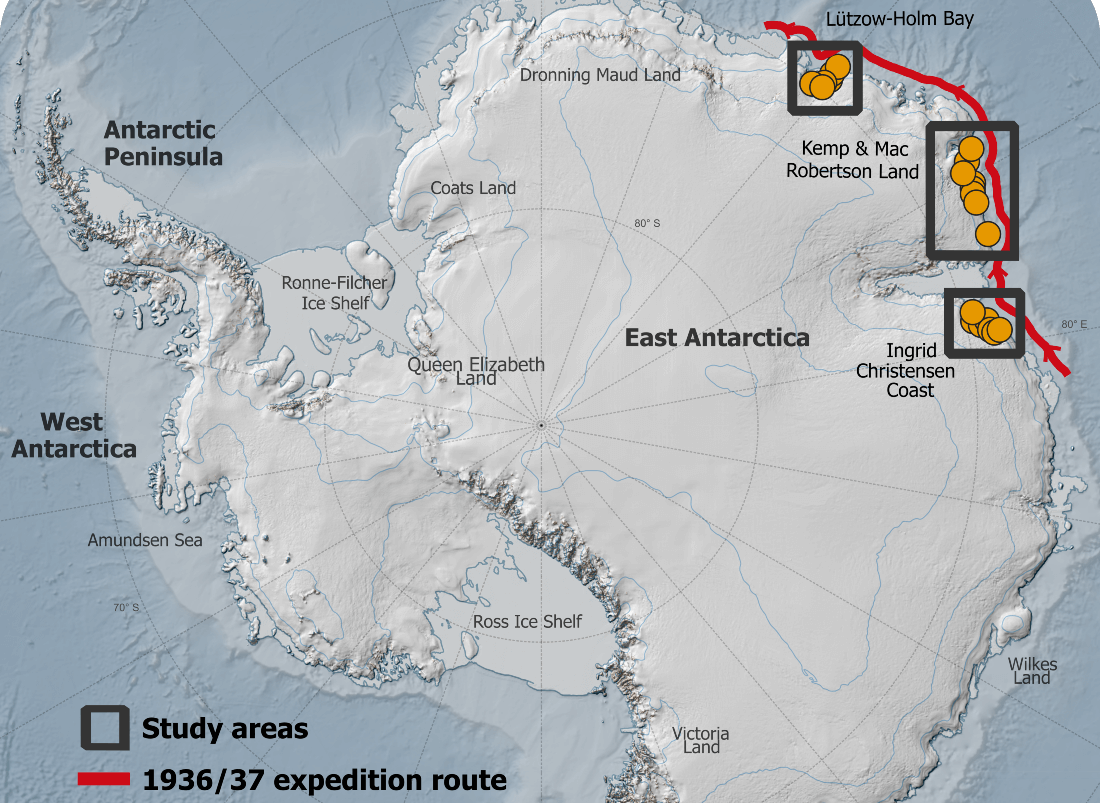

From aerial images to 3D models. Overview map.

Overview map.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/NK7KIFECCBHKJO5HDSXNAR27BM.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/EZDJNKSDS5EAPJYTXLJ4TMX3WA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/HBRTACVKUBGR5KJKLASZ5VA7PQ.jpg)