Three women ignite the flames of curiosity and adventure which lay dormant within so many of us, by deepening our understanding of the synergy between nature and humanity—and by doing so radically, through a voyage across the North Atlantic on Mara Noka, a 50-year-old wooden catamaran.

From FieldMag by Ellen Eberhardt

In 2022 three women crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a wooden catamaran

to document plastic pollution and find adventure, here's how

In June 2022, Alizé Jireh and Lærke Heilmann were at Red Beard Farm in Wilmington, North Carolina buying 15 pounds of sweet potatoes, onions, tomatoes, and other sea-worthy produce.

They even got to pull some vegetables straight from the earth, a memory that brought Heilmann comfort when cooking with them in a tight galley kitchen a month later, miles away from land, with nothing green in sight.

In June 2022, Alizé Jireh and Lærke Heilmann were at Red Beard Farm in Wilmington, North Carolina buying 15 pounds of sweet potatoes, onions, tomatoes, and other sea-worthy produce.

They even got to pull some vegetables straight from the earth, a memory that brought Heilmann comfort when cooking with them in a tight galley kitchen a month later, miles away from land, with nothing green in sight.

Photo by Alizé Jireh

At the farm, Heilmann and Jireh were completing one task in a long line of chores to prepare for a voyage like neither had embarked on in their lives.

Instead of taking the veggies home to a refrigerator, they brought them back to a 50-year-old catamaran called Mara Noka, and the boat's owner and captain, Kiana Weltzien.

The three women had been living on the vessel for a month, preparing the ship—and themselves—to sail across the Atlantic Ocean from Beaufort, North Carolina, to Flores, Portugal for a project called Women and the Wind.

Instead of taking the veggies home to a refrigerator, they brought them back to a 50-year-old catamaran called Mara Noka, and the boat's owner and captain, Kiana Weltzien.

The three women had been living on the vessel for a month, preparing the ship—and themselves—to sail across the Atlantic Ocean from Beaufort, North Carolina, to Flores, Portugal for a project called Women and the Wind.

But they had to wait for the right conditions.

From left: Kiana Weltzien, Lærke Heilmann, and Alizé Jireh

When the right winds did strike, Weltzien, Heilmann, and Jireh planned to make the crossing in 30 days.

They would document the journey in order to study and highlight plastic pollution throughout the Gulf Stream and to inspire others, especially women, to undertake momentous journeys of their own.

Photo by Alizé Jireh

The first roots of the idea came up in 2017, when Weltzien discovered Mara Noka floating in a Panamanian bay.

She bought the boat on a whim, upending plans for a solo backpacking trip through South America.

She'd already been traveling the world by boat for more than two years after quitting a career in real estate; she had been exposed to life at sea first by a family she worked as an au pair for and then again as a crew member on a 70-foot-long Polynesian voyaging canoe.

Growing up between Brazil and Florida exposed her to various water sports, but it was only after those formative years as an adult that Weltzien embraced a dream of becoming a fortified, professional sailor.

Buying Mara Nokawas another dream realized—now she was the captain of her own ship.

The Clean Ocean Project

is a non-governmental organization based on Fuerteventura, Canary

Islands. It was founded in 2002 by Wim Geirnaert with a simple approach:

everybody is part of the problem - and the solution.

For

the last 20 years, the organization has removed tons of trash from

beaches all over Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Morocco, Brazil, El Salvador,

and Belgium.

Besides

cleaning the beaches, the goal of the Clean Ocean Project is to

educated people about the issue of ocean waste and create awareness

towards more sustainable solutions.

Weltzien was living and sailing on Mara Noka in January 2020 when she arrived in the Canary Islands, where she met Heilmann at a party.

Beyond a shared passion for the ocean and its care, both women spoke Portuguese, and both had a fake tooth; coincidences that cemented a fast bond.

Heilmann was born and raised in a hippie commune in Denmark, where she spent summers sailing with family.

While she wasn't particularly interested in the sport, she grew passionate about the ocean, and eventually, she moved to the Canary Islands after falling in love with the surf and the slower way of life.

At the time of their meeting, Heilmann was working as a Project Coordinator for the Clean Ocean Project, an organization dedicated to beach clean-ups and ocean conservation education worldwide.

It wasn't long after that first meeting that they began dreaming of a transatlantic voyage drawn from a desire to shine a light on plastic pollution in the ocean and, of course, a natural call toward adventure.

The first step would be to repair Mara Noka—the old boat required lots of TLC after years at sea.

Photo by Alizé Jireh

"I thought I was going to die on this trip.

I was very certain of that."

I was very certain of that."

Photo by Lærke Heilmann

When the pandemic hit, dreams of going anywhere came to a screeching halt worldwide, but it gave Weltzien and Heilmann more time to plan.

Finally, in February of 2021, Weltzien took Mara Noka out of the water and into a boatyard in St.

Augustine, Florida, where her grandmother lives.

Heilmann joined her four months later, and they planned to repair Mara Noka and set sail in a few weeks.

In actuality, the repairs took a full year.

With no prior experience in shipbuilding besides Weltzien's knowledge of mixing epoxy, the pair trialed and errored their way through the process, documenting it through photos and reels on the Women and the Wind Instagram page.

Friends and family visited to help and offer advice, and one experienced shipbuilder shared his expertise, making occasional appearances to offer advice, sometimes sage, like "listen to the boat."

Finally, in February of 2021, Weltzien took Mara Noka out of the water and into a boatyard in St.

Augustine, Florida, where her grandmother lives.

Heilmann joined her four months later, and they planned to repair Mara Noka and set sail in a few weeks.

In actuality, the repairs took a full year.

With no prior experience in shipbuilding besides Weltzien's knowledge of mixing epoxy, the pair trialed and errored their way through the process, documenting it through photos and reels on the Women and the Wind Instagram page.

Friends and family visited to help and offer advice, and one experienced shipbuilder shared his expertise, making occasional appearances to offer advice, sometimes sage, like "listen to the boat."

As they deconstructed the boat, they began to understand its structure, and rebuilt from there.

After a year of sanding, sawing, painting, and gluing in the hot Florida sun, in May 2022, Mara Noka was finally ready for the water, complete with a fresh coat of paint and a hand-carved nameplate on a repurposed blank of original Panamanian sour cedar decking.

At the end of the month, Mara Noka, Weltzien, and Heilmann sailed from St. Augustine to Beaufort, North Carolina, to prepare for their final departure and to pick up their third crew member, photographer and filmmaker Alizé Jireh.

After a year of sanding, sawing, painting, and gluing in the hot Florida sun, in May 2022, Mara Noka was finally ready for the water, complete with a fresh coat of paint and a hand-carved nameplate on a repurposed blank of original Panamanian sour cedar decking.

At the end of the month, Mara Noka, Weltzien, and Heilmann sailed from St. Augustine to Beaufort, North Carolina, to prepare for their final departure and to pick up their third crew member, photographer and filmmaker Alizé Jireh.

Photo by Alizé Jireh

All while Weltzien and Heilmann were remaking Mara Noka, Jireh was keeping up over Instagram, and she became enchanted by the two women restoring a 50-year-old catamaran by hand.

Born and raised in the Dominican Republic, she too had spent her childhood around the water and had vivid dreams of sailing.

At 16, she started shooting documentary photo work and started traveling with it, eventually connecting with Weltzien while working at a production company in South Africa.

The two stayed in contact, and during a trip to St. Augustine in 2021, Weltzien invited her to the boatyard to check out the progress on Mara Noka.

Jireh was smitten with the whole operation.

Half a year later, Weltzien sent her a message asking if she'd not only like to come along for the voyage, but also capture the experience for a planned documentary.

With no prior sailing experience save those childhood dreams, Jireh responded with a resounding yes.

"For me, it was no question about it," she says.

With Mara Noka repaired and Jireh on board, the small crew spent most of the early summer waiting to set sail and growing accustomed to the boat, and each other.

For Weltzien, who had been happily sailing solo on Mara Noka for years, adjusting to traveling with others would be one of the most challenging aspects of the journey ahead.

"I'm a solo sailor," Weltzien explains.

"So to sail with people, I needed a purpose. And the purpose is to spread this message of 'if we can do anything, you can do anything.'"

Born and raised in the Dominican Republic, she too had spent her childhood around the water and had vivid dreams of sailing.

At 16, she started shooting documentary photo work and started traveling with it, eventually connecting with Weltzien while working at a production company in South Africa.

The two stayed in contact, and during a trip to St. Augustine in 2021, Weltzien invited her to the boatyard to check out the progress on Mara Noka.

Jireh was smitten with the whole operation.

Half a year later, Weltzien sent her a message asking if she'd not only like to come along for the voyage, but also capture the experience for a planned documentary.

With no prior sailing experience save those childhood dreams, Jireh responded with a resounding yes.

"For me, it was no question about it," she says.

With Mara Noka repaired and Jireh on board, the small crew spent most of the early summer waiting to set sail and growing accustomed to the boat, and each other.

For Weltzien, who had been happily sailing solo on Mara Noka for years, adjusting to traveling with others would be one of the most challenging aspects of the journey ahead.

"I'm a solo sailor," Weltzien explains.

"So to sail with people, I needed a purpose. And the purpose is to spread this message of 'if we can do anything, you can do anything.'"

Although Heilmann and Jireh were equally dedicated to spreading their intended message, simply surviving the trip proved the tallest hurdle.

"I thought that it would be my last time on earth," Jireh says.

"I thought I was going to die on this trip. I was very certain of that."

"To sail with people, I needed a purpose. And the purpose is to spread this message of 'if we can do anything, you can do anything.'"

"I thought that it would be my last time on earth," Jireh says.

"I thought I was going to die on this trip. I was very certain of that."

"To sail with people, I needed a purpose. And the purpose is to spread this message of 'if we can do anything, you can do anything.'"

Photo by Alizé Jireh

On June 27, 2022, Mara Noka officially set sail.

For the next 30 days, the women went without technology, the only connection to the outside world via a satellite phone and a friend, who posted updates to Instagram on behalf of the crew.

Even Jireh, who kept her camera rolling for the better part of the voyage, waited until landfall to review more than 100 hours of footage captured during the trip.

For 30 days, it was just Weltzien, Heilmann, Jireh, Mara Noka, and the sea.

In the beginning, the ocean welcomed them with calm conditions, but still, each crew member battled personal challenges.

Jireh fell seasick almost immediately and remained so for two weeks.

Heilmann tested positive for COVID just a few days in.

And Weltzien was navigating living with two inexperienced sailors on a boat and in an ocean that had previously brought her seclusion and peace.

The women adjusted to their new reality slowly.

"I feel like we didn't talk much for those first two weeks," Heilmann says.

"We were all in our little zone."

For the next 30 days, the women went without technology, the only connection to the outside world via a satellite phone and a friend, who posted updates to Instagram on behalf of the crew.

Even Jireh, who kept her camera rolling for the better part of the voyage, waited until landfall to review more than 100 hours of footage captured during the trip.

For 30 days, it was just Weltzien, Heilmann, Jireh, Mara Noka, and the sea.

In the beginning, the ocean welcomed them with calm conditions, but still, each crew member battled personal challenges.

Jireh fell seasick almost immediately and remained so for two weeks.

Heilmann tested positive for COVID just a few days in.

And Weltzien was navigating living with two inexperienced sailors on a boat and in an ocean that had previously brought her seclusion and peace.

The women adjusted to their new reality slowly.

"I feel like we didn't talk much for those first two weeks," Heilmann says.

"We were all in our little zone."

They remained distant throughout the beginning of the journey, in part as a natural reaction to a new lifestyle, and then later they were forced to due to two weeks of bad weather.

But there were moments of connection, too.

They shared all their meals, a ritual that remained with them through the duration of the voyage.

"One thing I think we always did together—except for during the peak of the storm when [Heilmann and Jireh] were my prisoners locked below in the dungeon—was eat together," Weltzien explains.

But there were moments of connection, too.

They shared all their meals, a ritual that remained with them through the duration of the voyage.

"One thing I think we always did together—except for during the peak of the storm when [Heilmann and Jireh] were my prisoners locked below in the dungeon—was eat together," Weltzien explains.

Photo by Lærke Heilmann

Photo by Alizé Jireh

On the seventh day, the winds started to pick up and were followed by weeks of rain, 10-20 foot waves, torn sails, and gear tossed overboard.

The three women rotated between sleepless nights in water-soaked beds, sticky and wet from the constant saltwater leaking through the ½-inch plywood into their sleeping quarters.

Weltzien was often busy manning the boat in the swell, while Heilmann and Jireh rotated between helping with tasks on board and taking shelter in the cabin below, intimated by the full force of the weather.

Throughout it all, Jireh kept her Panasonic GH 5 camera rolling in 4K (between taking breaks to throw up).

Her equipment survived the trip, but barely.

"That shit dropped so many times," she says.

"The screen stopped working." Both Weltzien and Heilmann were impressed with Jireh's abilities to create in an environment that was literally shifting below her feet.

"It's so impressive having seen the other side," Heilmann says.

"Seeing her with her camera, throwing up."

To the crew, the camera started to develop a personality of its own, an electronic Wilson to their collective Tom Hanks.

"Being a tiny little speck of a boat in the middle of the ocean, seeing trash every day makes you realize that the trash is absolutely everywhere."

Photo by Alizé Jireh

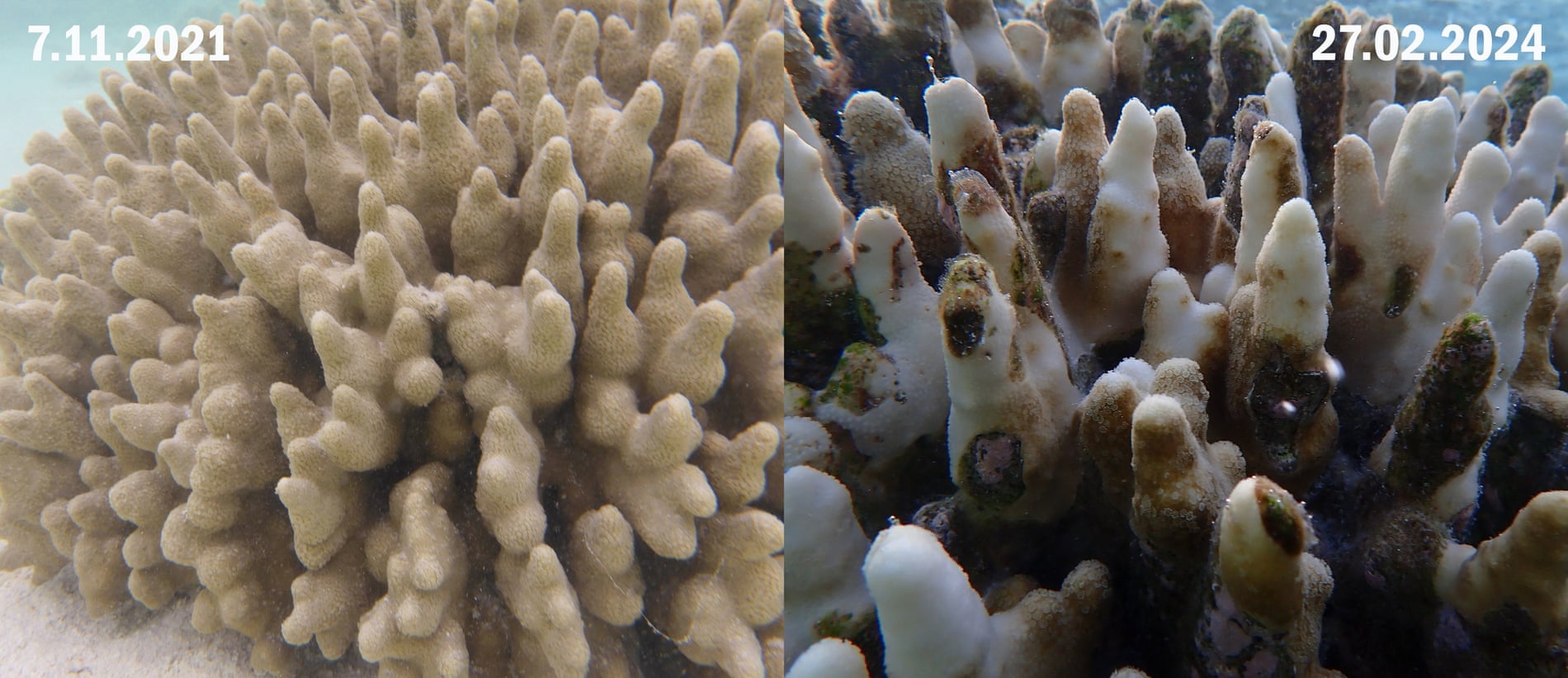

Another constant was the trash they saw in the water.

Even out to sea, pieces of plastic would float by every day.

Between collecting what they could and their own gear lost during storms, it was hard not to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount going into and coming out of the sea.

"Being a tiny little speck of a boat in the middle of the ocean, seeing trash every day makes you realize that the trash is absolutely everywhere," Weltzien says.

They did what they could before, during, and after the voyage, fishing trash out of the ocean and participating in beach clean-ups when on land.

"You just have to focus on one solution to the problem at a time," says Heilmann.

On their 19th day at sea, just over halfway through the voyage, the sun reappeared with a small swell and light winds.

To celebrate, the crew broke out a bottle of red and their lingerie, a ritual they had planned before setting sail.

Buoyed by the shifting seas, amidst clothing and blankets hung to dry, they looked ahead to the remainder of the voyage in good spirits.

Photos by Alizé Jireh

And the ocean seemed to reward them for surviving those initial trials; the remaining 10 days held with good weather, and after surviving the turbulent seas together, they experienced its bounty.

They talked more, slept on the deck under the night skies, listened to music, read, journaled, and above all else, indulged in the vastness of their surroundings and the lessons of life on the water.

Dolphins, whales, and seabirds paid visits.

Heilmann caught her first fish, a mahi-mahi, and spent two days crafting a pirate flag emblazoned with a skeleton mermaid.

Weltzien moved back to her normal sleeping quarters from the 12-inch wide bench in the galley she'd been using, and Jireh finally managed to keep food down.

One day out from landfall, all three women anticipated their arrival with a flood of emotions.

"I hate arriving," Weltzien says.

"It's exciting. It's great, it's beautiful, but it's just like it's your bubble bursting. It's your reality that you thought was real for so long. Just poof."

During their month at sea, the boat and their life aboard it had been a departure from the burdens of modern living, a gateway to complete symbiosis with nature.

Yes, certain parts of the voyage had been extremely challenging, but they had all consciously agreed to the perils the Atlantic might present.

Life at sea was expansive and vast, and their lifestyle reflected the same.

Reaching land, where rigid thoughts, schedules, and structures rule life suddenly seemed more daunting than 15-foot waves.

"Everything has to be explained in words that are somehow not enough to explain what you felt," Heilmann shares.

"It's very overwhelming."

Yes, certain parts of the voyage had been extremely challenging, but they had all consciously agreed to the perils the Atlantic might present.

Life at sea was expansive and vast, and their lifestyle reflected the same.

Reaching land, where rigid thoughts, schedules, and structures rule life suddenly seemed more daunting than 15-foot waves.

"Everything has to be explained in words that are somehow not enough to explain what you felt," Heilmann shares.

"It's very overwhelming."

Photos by Alizé Jireh

On the night of July 25, 2022, cell phones buzzing with incoming messages from the past month, Mara Noka cruised past other moored boats and dropped anchor in a harbor off Flores, an island in Portugal's Azores archipelago.

The voyage was complete.

For the next month, the crew debriefed while sailing around the Azores together, and waited for the right conditions to deliver Heilmann and Jireh to their departing flights.

After goodbyes, Weltzien sailed by herself to Brazil, a crossing that lasted 43 days, realizing along the way that she missed their company.

Today, the three women are spread between Brazil, the Canary Islands, and the US, but led by Jireh, they're editing and producing the Women and the Wind documentary.

They plan to overlay Jireh's ethereal footage with journal entries from the trip, and they've also set up a Kickstarter to help meet production costs.

Weltzien, Heilmann, and Jireh are still processing the voyage.

They share what they can put into words about how it changed them.

"I feel a lot of little things that maybe mattered before, I really don't think they matter at all," Heilmann explains "I think I've never done anything that long with so many uncertainties and so many reasons that you shouldn't. And it feels really powerful."

The voyage was complete.

For the next month, the crew debriefed while sailing around the Azores together, and waited for the right conditions to deliver Heilmann and Jireh to their departing flights.

After goodbyes, Weltzien sailed by herself to Brazil, a crossing that lasted 43 days, realizing along the way that she missed their company.

Today, the three women are spread between Brazil, the Canary Islands, and the US, but led by Jireh, they're editing and producing the Women and the Wind documentary.

They plan to overlay Jireh's ethereal footage with journal entries from the trip, and they've also set up a Kickstarter to help meet production costs.

Weltzien, Heilmann, and Jireh are still processing the voyage.

They share what they can put into words about how it changed them.

"I feel a lot of little things that maybe mattered before, I really don't think they matter at all," Heilmann explains "I think I've never done anything that long with so many uncertainties and so many reasons that you shouldn't. And it feels really powerful."

Links :

A Healthy brain coral rests under Port of Miami regardless of extreme heat in Miami, Flordia, U.S., July 14, 2023. REUTERS/Maria Alejandra Cardona/File Photo

A Healthy brain coral rests under Port of Miami regardless of extreme heat in Miami, Flordia, U.S., July 14, 2023. REUTERS/Maria Alejandra Cardona/File Photo