see GeoGarage news

Saturday, October 10, 2020

New Zealand (Linz) update in the GeoGarage platform

see GeoGarage news

Friday, October 9, 2020

Exploring the Arctic circle on board scientific superyacht Yersin

From Boat International by Sophie Wilson

Yersin was built to combine scientific exploration with all the comforts of a superyacht.

Owner François Fiat and Captain Jean Dumarais tell Sophia Wilson the story of this ice breaker's first exploration in the Arctic Circle

When 76.6-metre Yersin hit the water back in 2015, it marked a momentous shift in the world of expedition yachts.

Not only had the boat, named after 19th-century physician and bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin, been designed to explore the globe, she had also been created to protect it as one of the world’s only sustainable, clean and green vessels.

Her vast autonomous range, Ice-Class hull and sustainable credentials were well documented at the time but last year she finally got to flex her exploration muscles on her debut adventure to the Arctic Circle.

“I wanted to test the vessel,” says François Fiat, who devised and owns Yersin.

“She was conceived specifically for these regions.” As tests go it was fairly extreme, with the yacht visiting Iceland and Greenland before crossing Baffin Bay and cruising down Baffin Island and on through Labrador, Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

At her helm during the voyage was Captain Jean Dumarais who, having been involved in the yacht’s construction, was equally keen to test her capabilities.

“It was preparation for future trips over there,” he explains.

“The crew are not on board for the glitz and glamour of the Med.

They want to go exploring.”

The yacht first headed north at the end of July, stopping in Iceland, before making her way to Greenland’s west coast.

After clearing in Nuuk, Yersin headed to Ilulissat, which is home to the Jakobshavn Glacier.

“It is one of the most productive glaciers in Greenland, which makes the largest amount of ice,” says Captain Dumarais.

“Most of the icebergs that you meet are coming from that glacier.” At approximately 65 kilometres long and two kilometres thick, it’s famous for being the source of the iceberg that caused the Titanic to sink.

As the yacht cruised further north, it also visited Eqi Glacier, which is accessible only by boat and was one of the captain’s highlights.

“Polar explorer Paul-Émile Victor had a base there when he did his crossing of Greenland and you still find little houses attached to the rock.

It is amazing that they are still there in this polar region so many years after he visited,” he says.

Fiat was equally entranced by Greenland’s northern territories.

“The most fascinating thing for me was the immensity of the landscape,” he says.

“We saw the ice caps from the sea and watched glaciers fall into the water.

The air is very crisp and clear.” The pure air quality actually created an unforeseen issue for Captain Dumarais as it became increasingly hard to judge the distances to the shore.

“Looking at the glacier it seems that it is near, but when you check it on a radar it is much further away than it appears,” he explains.

“You have to verify the distance before you go over there in a tender, especially in ice-covered water.

Otherwise it can take a very long time.”

As well as its stunning natural credentials, the trip also provided a fascinating insight into remote communities.

“There are two or three main cities but after you head north there are only a few houses and a few dogs,” says Dumarais.

“The towns have roads, but they stop at the end of each town, so [people] have to take a boat to visit other settlements.” The trip made Dumarais aware of the uncertain future that these traditional set-ups face.

“You can see the movement of the population; a lot of people have moved to the major cities leaving only a few people in the villages.

You will see a village with 20 houses and probably 15 of them are now uninhabited.

It makes you realise just how fragile this equilibrium is,” he adds.

From Greenland’s Uummannaq, Yersin crossed Baffin Bay to Baffin Island, the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world.

This stretch of coast proved to be one of the best destinations for spotting sea life and polar bears.

On this trip they chose not to have a naturalist on board to help them find bears, but they still had success.

“We saw five, including a couple of cubs,” says Dumarais.

“They definitely see you more than you see them, though.

As they are white-on-white it is very difficult to spot them.”

One of the key parts of Yersin’s design is her polyvalent room on the main deck, which can be used as a laboratory, media room or classroom as required.

Even though this trip was not specifically for scientific purposes, scientists and television reporters did come on board for parts of the adventure.

“We did some on-site fact-finding research,” explains Fiat.

“In Iceland, we [studied] whales.

In Greenland, we surveyed the formation of ice and glaciers falling in the fjords.

In Nova Scotia, where the currents are very strong, we studied scallops with the scientists from the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.”

One of the biggest challenges of the voyage was that so much of the route was uncharted.

“No map is available – land maps do exist, but it’s not possible to know where the seabed is or how deep the water is beneath the vessel.

It could be 10 metres or 500 metres,” says Fiat.

To ensure the route was safe, Yersin used sonar and sent the tenders in front to navigate.

“We had to cruise slowly and make our own map,” adds Fiat.

“When we were unfortunate enough to encounter fog, we had no other choice than to stop, which was quite distressing.”

The lack of charted maps was particularly perilous as the yacht cruised south from Baffin through the remote region of Labrador.

“The area is not charted; it’s just a blank page,” recalls Dumarais.

“It is treacherous because you can find rocks 50 miles [80 kilometres] offshore.” The yacht used the trip to help plot a safe route for future visitors.

“Vessels that go to Labrador make their own way and record their route and send it to the team that creates charts, who will then list the vessel’s route as a new route on the map.

Our voyage is now charted,” explains Fiat.

During its time in Labrador the yacht went for periods of longer than a week without seeing any other boats or humans.

“In Greenland you can find some villages but in Labrador there is no one,” says Dumarais.

Labrador also saw the yacht face some of the most challenging weather conditions.

“We had good weather for most of the trip but of course we had a storm as well.

If you are visiting this area you expect this,” he says.

“We had to hide in a bay and protect ourselves.

We were fine but I lost all my instruments because the winds were over 100 knots an hour.”

With such a remote cruising route, provisioning was also one of the biggest considerations that had to be factored in.

“The preparations and storage start way before the trip.

You have to be very organised,” says Dumarais.

“Once you are further north you won’t find anything; you are happy if you find 10 apples.” The crew were able to catch some cod en route, which they used to cook fish and chips, and also purchased some halibut in Greenland.

“We made a local dish from the South of France.

It was quite amazing to have a glass of wine and that type of food so far from home,” says Dumarais.

During the trip they were also able to have some meals on the sundeck using the yacht’s teppanyaki hot plate.

“These are some of the best memories, when you are able to eat something unique in a place where you wouldn’t normally think it was possible,” he adds.

As autumn approached, the yacht continued to make her way south, including a stop in the Bay of Fundy, which is famed for having the highest tide in the world.

As the seasons changed, those on board were fortunate enough to see the Northern Lights frequently.

“We saw splendid aurora borealis,” says Fiat.

“We were there in September, and from 10pm to 5am or 6am; the auroras constantly move above your head. It is not a rare phenomenon at all.”

After making it as far south as Nova Scotia, Yersin crossed to Bermuda before returning to her native South of France.

So, did Yersin pass the test? According to her owner, yes – with flying colours.

“Yersinis perfectly equipped and she reacted very well, as anticipated.

To make this kind of trip you need an appropriate vessel; I know of only one, and that is Yersin,” he says.

For Fiat, it is her combination of robustness and luxury that make her perfect for such a voyage.

“Of course, there are many ice breakers out there, but without comfort on board.

It is lovely to return after an expedition and enjoy a sauna, relax in a nice [suite], watch a movie and dine on sophisticated cuisine,” he adds.

Captain Dumarais agrees that there is no other yacht he would rather take to this part of the world.

“If you have a boat as silent as ours, you can cruise along like you are visiting the place on a magic carpet.

You can barely see a wake on the back of the boat,” he says.

“It was breathtaking.”

This trip is clearly just the beginning of Yersin’s adventures and Fiat has even more ambitious plans for her in the future.

“My dream trip would be the Northwest or Northeast Passage,” he reveals.

“We stopped on its doorstep and it should be feasible as Yersin has all the capabilities to explore this route.”

Yersin is for sale (for the first time since she was built) with Fraser for €79.5 million.

(see FraserYachts)

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Why the super-rich are taking their mega-boats into uncharted waters

Thursday, October 8, 2020

See the classified Russian maps that fell into enemy hands

From National Geographic by Greg Miller

Russian cartographers mapped their homeland in detail—making these secret charts invaluable to the Nazis, the U.S. Army, and the CIA.Like stamps on a passport, the stamps on these captured Russian military maps tell a story—for the maps, it's often one of intrigue and globetrotting.

Stamps emblazoned with national insignia reveal that some of these secret maps were captured by the Nazis and others by the U.S. Army during World War II.

Several maps bear stamps suggesting they passed through the hands of multiple foreign military and intelligence agencies.

Several stamps, including a purple stamp with the Nazi eagle and

swastika symbol, appear on this 1936 Russian military map of Belarus

The Russian text at top right indicates that the map was “not subject to disclosure.”

They were made between 1883 and 1947, and they were never meant to be seen by outsiders, says IU map librarian Theresa Quill.

Many are marked “СЕКРЕТНО” (SECRET) or “НЕ ПОДЛЕЖИТ ОГЛАШЕНИЮ” (NOT SUBJECT TO DISCLOSURE) in the top right corner.

This detail from the Leningrad map shows the skill of the Russian military cartographers who made it.

This detail from the Leningrad map shows the skill of the Russian military cartographers who made it. A stamp near the bottom of the Leningrad map indicates that

it was received by the CIA right around the outbreak of the Cold War.

A stamp near the bottom of the Leningrad map indicates that

it was received by the CIA right around the outbreak of the Cold War.This map of the villages around Leningrad (St. Petersburg) bears several stamps at the top and bottom.

“Atlasblatt” stamped in red at top left means “atlas sheet” in German, suggesting this map was once bound together with others.

This map of Tilsit (now Sovetsk) area bears a faded purple stamp from the CIA near the bottom left corner. This detail from the previous map shows the terrain, waterways, and buildings around Tilsit (Sovetsk).

This map of Tilsit (now Sovetsk) area bears a faded purple stamp from the CIA near the bottom left corner. This detail from the previous map shows the terrain, waterways, and buildings around Tilsit (Sovetsk). “A number of the maps from the 30s have a German stamp with a swastika on them, so we think they were captured in the field by German troops and then later captured in the field by American troops during World War II,” Quill says.

“Many have Army Map Service stamps or CIA stamps on them as well.”

The maps would have provided valuable military intelligence for their foreign captors.

Russian military cartographers are renowned for their skill, and their maps of Russia and Eastern Europe were unsurpassed in their detail and accuracy.

Most likely through many different routes, thousands of these maps ended up at the Library of Congress, which over the years has distributed copies to university map libraries around the country.

“Not all of them have the same stamps, so it’s sort of like piecing together a mystery,” Quill says.

Most of the maps in the IU collection cover Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, the Baltic states and areas of western Russia.

They provide a snapshot of a region that underwent tremendous change during the first half of the 20th century, making them a valuable resource both for historians and other scholars, Quill says.

“These are still some of the most detailed and authoritative maps for that part of the world, particularly for that time frame.”

The maps have also been used by people trying to track down their family history, especially when they have roots in places that don’t appear on modern maps.

“So many small villages that existed before World War II don’t exist anymore,” Quill says.

In addition, for reasons that remain mysterious, the university’s website for the maps has also gotten a lot of traffic from an online forum in Russia for treasure hunters.

Quill and her IU colleague Michelle Dalmau recently won a grant to digitize and catalogue the Russian military maps to make them more accessible for researchers.

The work will include documenting the stamps on each map.

The stamps alone don’t tell the whole story, though.

In most cases there’s no way to tell when and where a given map was captured.

It’s impossible to know just based on the stamps it bears whether a map was seized in the heat of battle or simply sat in a warehouse that changed hands at the end of the war.

If only maps could talk.

Links :

- National Geographic : Cold War Soviet military maps, captured Japanese military maps, and the CIA’s cartography center.

- GeoGarage blog : The Soviet military program that secretly ... / Inside the secret world of Russia's cold war ...

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

Mapping the Oceans

From Latham Quarterly by Helen M. Rozwadowski

How cartographers saw the world in the Age of Discovery.

Johannes Gutenberg printed his first Bible in 1455, and the first published sailing directions appeared thirty-five years later.

Print media encouraged the divergence of navigational information from material discussing the commercial prospects of trade at various ports.

Printing promoted the widespread distribution of geographic and hydrographic information, including maps, to readers throughout Europe at a time when literacy was on the rise and the spreading use of vernacular languages made such works available to non-scholars.

Discovery of the sea leaned heavily on geographical and maritime information available from learned sources, including Arabic texts and rediscovered Greek texts.

The Renaissance rediscovery of classical Greek learning included geographic writings of Herodotus, Aristotle, and Ptolemy, each of whom rejected the traditional view of an oceanic river flowing around a circular world.

Ptolemy’s Geography, restored to Europe from Byzantium early in the fifteenth century, countered the Earth island idea with a view that oceans were entirely separated by landmasses, a model challenged by Magellan’s achievement of sailing between oceans.

Europe’s explorers actively sought and exploited both academic knowledge and geographic experience in their systematic search for new trade routes.

Use of the sea ultimately rested on reliable knowledge of the ocean.

Fresh appreciation for empirical evidence fueled recognition of the value of experience, and the process of exploration included mechanisms for accumulating and disseminating new geographic knowledge to form the basis for future navigation.

At the outset of the discovery of the seas, portolan charts recorded actual experiences at sea.

These navigational aids provided mariners with compass direction and estimated the distance between coastal landmarks or harbors.

Utterly novel for their time, portolans were the first charts to attempt to depict scale.

Portolans created by fourteenth- and fifteenth-century explorers document Portuguese and Spanish discovery of Atlantic islands and the African coast and helped subsequent mariners retrace their steps.

Accuracy of portolans was best over shorter distances, and they became less useful when navigators steered offshore.

In contrast to creators of portolans, armchair cartographers compiled world maps of little use for actual navigation but which reflected shifting knowledge of oceans.

While manuscript maps had been produced alongside written manuscripts since antiquity, the earliest known printed map was included in an encyclopedia of 1470.

It represents the world schematically within a circle, in which the three continents of Asia, Europe, and Africa are surrounded by an ocean river and separated from each other by horizontal and vertical rivers that form a T shape—hence the name “T-O” to describe this kind of map.

Other early maps were based on Ptolemy’s work, on biblical stories or other allegories, or occasionally on portolans.

Cartographers created maps for patrons or in hopes of selling printed copies, generally seeking recent information about the ocean from a wide variety of sources, including published maps and books, manuscripts, reports from mariners and other voyagers, and, perhaps in a few cases, personal experience.

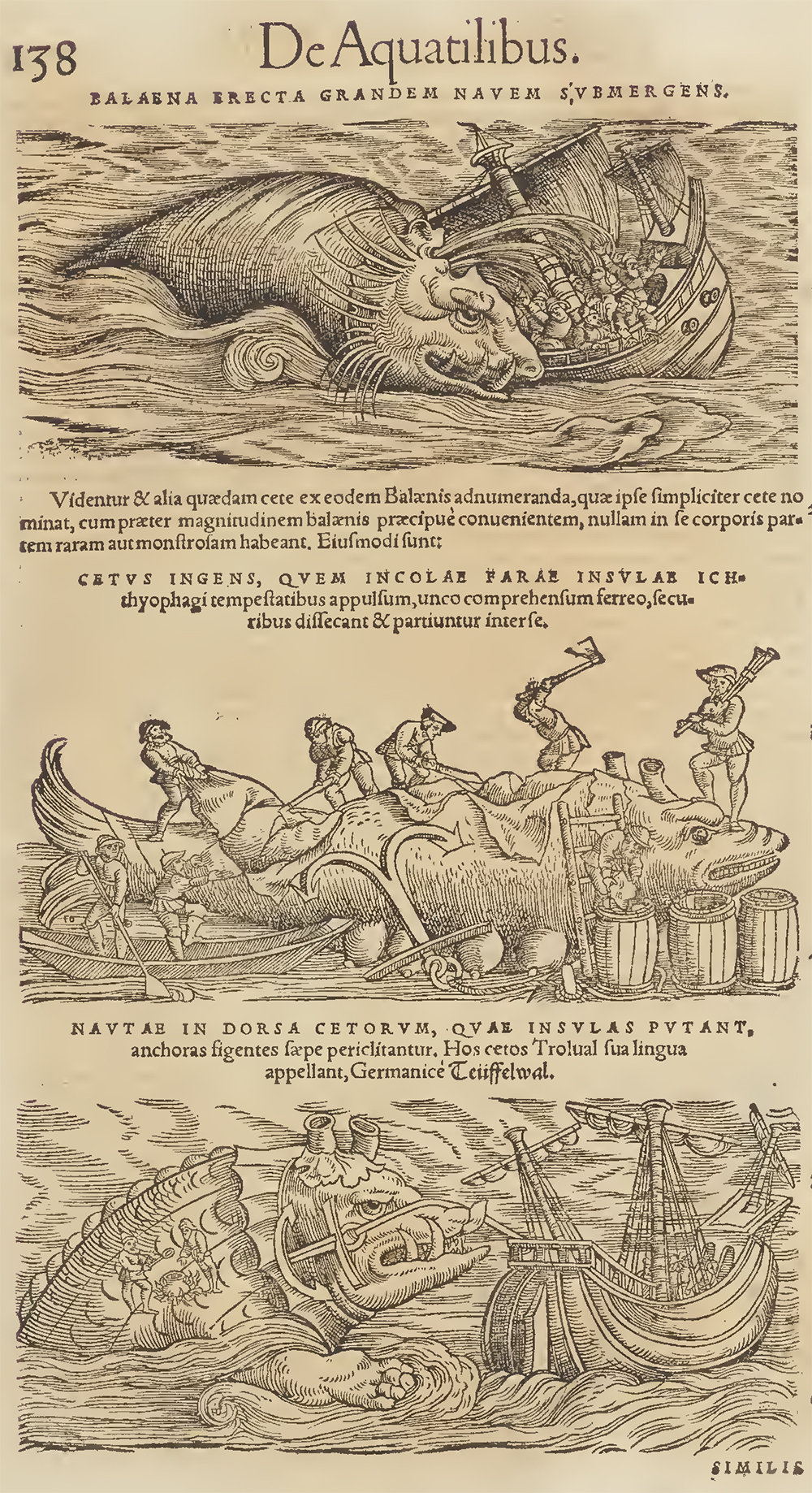

Medieval bestiaries, or illustrated compendia of animals, provided models for sea monsters that appeared on maps, but Renaissance cartographers also borrowed from classical images, such as stylized dolphins from ancient Rome.

Legends such as the tale from St.

Brendan of running aground on an island that turned out to be the back of a whale inspired pictures on maps of mariners making fires on the backs of enormous animals mistaken for oceanic isles.

Medieval maps that included sea monsters or other astonishing or exotic marine creatures often portrayed these as oceanic versions of terrestrial animals, such as sea dogs, sea pigs, or sea lions, following an ancient theory that the ocean harbored animals equivalent to those on land.

Although the majority of medieval maps and nautical charts of the Age of Discovery did not include sea monsters, the ones that do reveal both a rise of general interest in marvels and wonders and a specific concern for maritime activities that took place at sea, including in far distant oceans.

The more exotic creatures are often positioned on maps at the edge of the Earth, conveying a sense of mystery and danger and perhaps discouraging voyages in those areas.

Images of octopuses or other monsters attacking ships would seem to be warning of dangers to navigation.

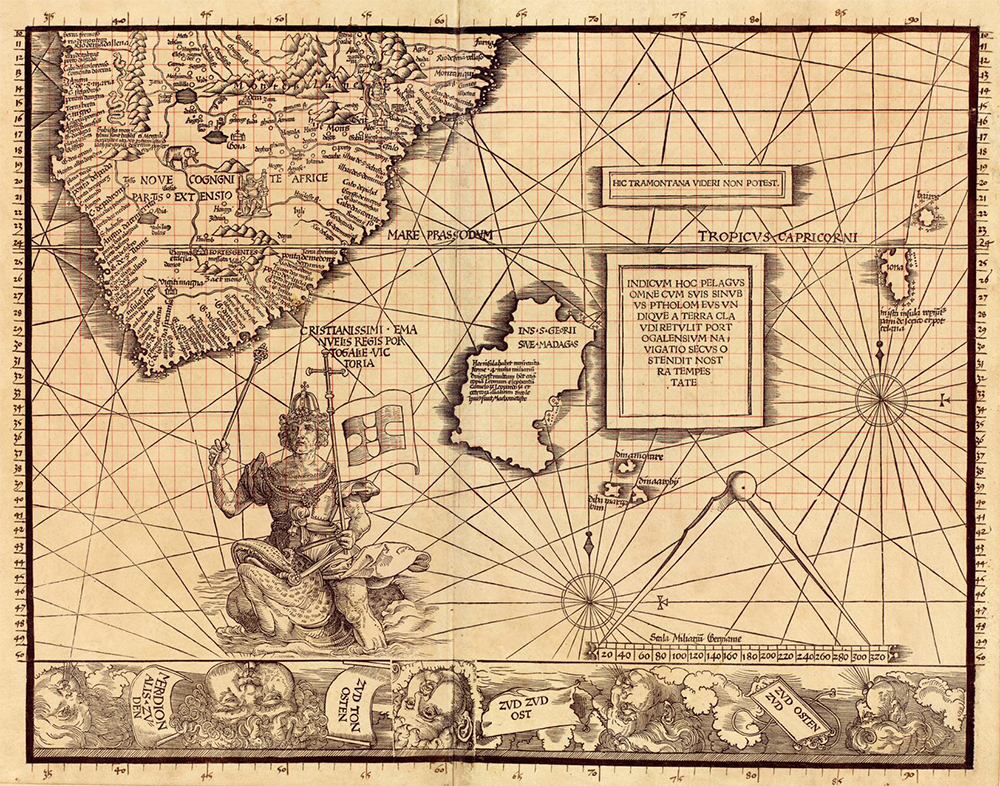

A striking depiction of King Manuel of Portugal riding a sea monster near Africa’s southern tip, from Martin Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta Marina, displayed Portuguese mastery and political control over the sea.

The most famous representations of sea monsters in the sixteenth century frolic on the Carta Marina created by the Swedish priest Olaus Magnus and published in 1539.

The map covers Scandinavia south to northern Germany, east to Finland, and including the Atlantic to the south and slightly west of Iceland.

Land is represented with much detail, but so too is the ocean.

There are real as well as nonexistent islands and ships carrying cargo or fishing.

The sea is full of dynamic marine creatures, some recognizable as whales, sea lions, lobsters, or other species of economic value but others more fantastic or menacing.

Monsters attacking ships from Protestant countries may reflect the exiled Magnus’ displeasure at reformation after Sweden broke from the Catholic Church.

In addition to his map, Magnus also wrote detailed descriptions of his sea monsters in his book, whose translated title is History of Northern Peoples (1555).

While some of his marine creatures derived from bestiaries or legend, such as his account of a two-hundred-foot sea serpent living near Bergen, Norway, others of his depictions were original, and some may reflect reports of unfamiliar animals.

Mariners returned home with stories of strange creatures they saw at sea, including giant whales and sharks, as well as narwhals with single helical tusks up to ten feet in length.

Until explorers discovered the truth, narwhal teeth were sold in Europe and the Far East as unicorn horns.

The European court knew the ocean to be the source of strange and precious objects such as coral, pearls, and mollusk shells, which began to appear in seventeenth-century cabinets of curiosities alongside dried sea horses, turtle shells, and shark’s teeth.

The Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner assembled existing knowledge about marine life in his 1558 Fisch-Buch (Fish Book), which listed about eight hundred creatures.

He drew upon mariners’ tales, requested drawings and specimens from sources throughout Europe, and traveled to the Venice fish market to study for several months.

Embracing the variety of living forms as proof of divine creation, Gessner’s work included both real and mythological creatures.

His Historia animalium, published over the course of the 1550s, featured a unicorn among the terrestrial animals, while his sea animals included mermaids, a walrus with feet, and a number of monsters taken from Magnus’ work.

Numerous other authors and cartographers similarly copied or borrowed Magnus’ influential images.

The detail captured and information conveyed in the ocean spaces of many maps testified to the extent, liveliness, and importance of maritime activity and its oceanic setting.

Representations of marine creatures and other cartographic choices revealed to the viewer of a map what was normally hidden, rendering the ocean as a thoroughly three-dimensional space full of life and activity.

Magnus depicted the sea’s surface as highly textured by filling all ocean space with horizontally oriented dotted lines, occasionally interrupted by wake from a moving vessel or a surfacing animal.

Textured surfaces, identifiable marine creatures or exotic and forbidding monsters, and ships busily prosecuting maritime work fill map space devoted to the ocean on many cartographic works produced through the sixteenth century.

The amount of such decorative detail on a map might depend on the amount of money a patron was willing to spend.

Medieval maps published in the first fifty years after the printing press often included textured oceans, represented sometimes with parallel lines and other times with broken, wavy lines.

Some allegorical maps likewise featured oceans filled with lines denoting a watery surface, calling attention to what might lie beneath, while other maps that divided ocean space by latitude and longitude left oceans blank but used sea creatures and ships as decorative elements symbolizing maritime activity.

One detail on the Magnus map would seem to speak to navigators.

In the area east of Iceland and extending to north of the Faroe Islands, there is a band of carefully drawn whorls, which modern oceanographers argue may represent the Iceland–Faroes front.

Here, cold Arctic water currents coming around the coast of Iceland mix with warmer water from the Gulf Stream flowing north to form strong eddies that could drive a ship off course.

Trade conducted between Iceland and the European continent by mariners of the Hanseatic League brought dried cod and other products from Iceland to exchange for grain, beer, wood, and textiles.

Navigators certainly noticed temperature differences and also variations in surface currents, and this information was likely conveyed to Magnus during visits to northern German cities.

One other map of Scandinavia from Brussels, made in the late fifteenth century, may portray this same oceanic feature also with a series of whorls.

In neither map are there such curls shown anywhere else in the ocean, suggesting they were meant to represent a specific feature, one no doubt long known by Hansa navigators and Vikings before them.

Maps became more useful to navigators when cartographers created projections that could represent the spherical Earth on the flat, printed page.

For open-ocean journeys, long-distance voyaging navigators turned to the Mercator projection (1569), which showed the latitude and longitude grid and corrected for the Earth’s curvature such that lines of a compass heading could be represented on the chart as straight lines or, as sailors called them, rhumb lines (loxodromes).

This made it possible to keep track on the chart of a route sailed by dead reckoning.

With the addition of celestial navigation, mariners could use observations of the height of stars or the Sun taken with quadrants to find their latitude and correct mistakes that arose from magnetic variation or dead reckoning navigation.

Mariners would not gain the ability to find their longitude until the late eighteenth century.

Knowledge recorded on Mercator projection charts prioritized actual observations, soon to be prized by scholars associated with changes wrought by the Scientific Revolution, generally understood to begin with Nicolaus Copernicus and the publication just before his death in 1543 of his model of the universe with the Sun rather than the Earth at the center.

Cartographer Gerard Mercator himself sought the newest and most trustworthy sources of information for his work, shifting from copying Magnus’ sea monsters in the terrestrial globe he created in 1541 to using recent natural history publications for his subsequent famous 1569 world map.

He moved his most exotic creatures from the regions around Africa, Asia, and the Indian Ocean, where most cartographers before then had placed sirens and other dangerous or mysterious monsters, to waters off South America and the Pacific Ocean, signaling the rise of geographic interest in these relatively less traveled parts of the globe.

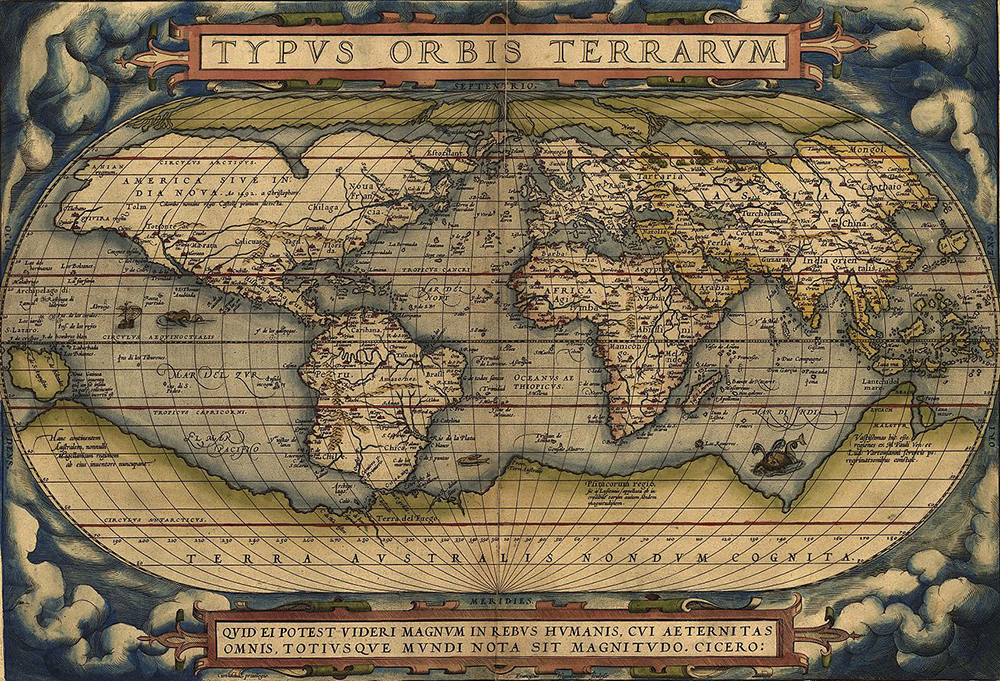

A friend and rival of Mercator, Abraham Ortelius, created a world map in 1570 that included elements by then common in visual representations of the ocean as well as some newer features.

He textured the sea’s surface with stippling over all of the ocean space on his map, but he also divided that space with lines of latitude and longitude.

There is one ship and two creatures that might be whales, possibly decorative elements but certainly also acknowledgment of maritime activity and a reference to the importance of whales as resources.

Other maps from later in the sixteenth century feature images of lifelike whales and of people whaling, including one of the North Atlantic and what is now Canada with an inset drawing of men, possibly Basques, harpooning one whale and flensing another.

This scene was copied from the first published print of Basque whale hunting at sea that had been produced a decade earlier.

This map also included whale-like monsters resembling sea monsters from older sources, but the trope of sea monsters on maps and charts was fading.

In an increasingly well-known world, monsters on maps made after the sixteenth century appeared to convey fancy or whimsy rather than danger.

Cartographers began to depict economically valuable marine animals realistically based on up-to-date natural history fostered by the growing experience of mariners.

Actual observations of nature replaced preoccupation with marvels and wonders.

Whales on charts transformed from threatening giants into swimming commodities and then disappeared entirely.

The occasional decorative ship, compass rose or nautical instrument on maps gestured to human maritime activity, but banished the ocean itself.

The gridded ocean space of the seventeenth century and beyond was most often left blank, without stippling or lines to denote the presence of the sea itself or to conjure the world hidden beneath its surface.

Blank ocean space on maps appears to reflect a revision of the sea from a dangerous and mysterious place into a knowable part of the natural world whose control enabled the exploitation of marine resources and the expansion of European power.

Tuesday, October 6, 2020

The Atlantic is awash with far more plastic than previously thought, study finds

Michael O'Neill/Science Source

From NPR by Rebecca Hersher

Scientists are trying to understand how much plastic humans are pumping into the ocean and how long it sticks around.

A study published this week says it may be much more than earlier estimates.

By some measures, the plastic trash that's floating on the surface of the water only accounts for about 1% of the plastic pollution that humans generate.

"If we are missing 99% of plastic that we thought we have put in, it has to be somewhere," says Katsiaryna Pabortsava, a researcher at the National Oceanography Centre in the United Kingdom.

She and her colleagues set out to look for the missing plastic debris.

It's known that tiny pieces of plastic, some too small to see with the naked eye, are present throughout the environment, including in drinking water, sea salt, beer and fish.

Studies have found these pieces, often called microplastics, deep in the Pacific Ocean and in the air above France's Pyrenees mountains.

But it's been unclear how much tiny plastic pollution is accumulating in oceans.

Pabortsava and her team looked at three types of microplastic pollution in the top 200 meters of the Atlantic Ocean, and found evidence that a colossal amount of plastic is hanging out below the surface of the water.

Article continues after sponsor message

The results, published this week in the scientific journal Nature Communications, focus on three types of plastic that are used in common food and other product packaging.

A study suggests there is more plastic pollution in the Atlantic Ocean than previously thought.

The new study finds that the total amount of plastic making its way into the Earth's oceans is likely higher than previous estimates suggest.

A previous study published in 2015 estimated that upward of 12 million metric tons of plastic trash made it into the oceans in 2010 alone.

Scientists only started trying to quantify how much plastic is in the ocean in the last decade.

That analysis was never meant to present a comprehensive picture of plastic in the oceans — it only looked at municipal waste and didn't account for plastic trash from ships or fish nets lost at sea.

Nor did it estimate how long plastic pollution stays in the ocean.

"There are still huge uncertainties about how much plastic goes into the ocean," Pabortsava says.

The new study adds to what's known but is still an incomplete picture.

It estimates that there is upward of 21 million metric tons of three common types of small plastic pollution in just the top 200 meters of the Atlantic.

It's a rough estimate — the researchers took samples at 12 locations up and down the Atlantic and extrapolated from there — and there could be even more plastic of other types.

Microplastic in the ocean comes from two main sources.

Tiny spheres of plastic, called microbeads, were a common ingredient in exfoliating soaps sold in the U.S. until the federal government banned their use in personal care products in 2015.

The European Union did the same last year.

But most tiny plastic bits are remnants of larger pieces of plastic broken down by waves and sunlight.

Microplastics below the surface of the ocean are bad news for the whole food chain.

Small ocean-dwelling creatures eat them, and the plastic makes its way into larger fish and shellfish that humans eat.

It's difficult to imagine that eating tiny bits of plastic is good for humans, but the potential health impact of microplastics is still unknown.

A 2018 study noted that seafood is a critical source of sustenance around the world and that scientists should focus on figuring out how long microplastics survive in the environment and how they affect human health.

Links :

- EcoWatch : Atlantic Ocean Holds 10x More Plastic Pollution Than Previously Believed, New Study Finds

- BBC : Microplastic in Atlantic Ocean 'could weigh 21 million tonnes'

- The Guardian : More than 14m tonnes of plastic believed to be at the bottom of the ocean

- CNN : There's 14 million metric tons of microplastics sitting on the seafloor, study finds

- The Conversation : We estimate there are up to 14 million tonnes of microplastics on the seafloor. It’s worse than we thought

Monday, October 5, 2020

For new robotic ships, Pentagon ignores China’s dangerous “phony war fleet”

From Forbes by Craig Hooper

A few days after the Pentagon released its annual report to Congress on “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” the Navy awarded six contracts to refine the requirements for the Navy’s future Large Unmanned Surface Vessel(LUSV).

The Pentagon report on China’s emerging military prowess telegraphed the Navy’s purported need for large unmanned surface vessels, trumpeting that China “has the largest navy in the world, with an overall battle force of approximately 350 ships and submarines”.

But, of all the worrisome things in China’s growing arsenal, China’s conventional Navy, in itself, is an odd threat to highlight.

While a strong conventional navy justifies the Pentagon’s interest in unmanned vessels, this was the wrong maritime threat to emphasize, and the report only made China’s conventional navy look far stronger than it is.

A more provocative analysis might note that, despite China’s lofty maritime aspirations, China’s conventional naval force is undersized and still dominated by a plethora of tiny, low-endurance coastal defense platforms—platforms that are little threat beyond Chinese-held waters.

And yet, while the Pentagon took to the fainting couch over China’s small conventional Navy, the Department of Defense turned an almost blind eye to China’s massive “Phony War Fleet”, a giant array of low-tech, “non-military” maritime forces.

China uses this force—a massive Coast Guard, civilian “fishing fleet” militia and an array of “ad hoc public/private” logistical partnerships—to change status quo in the maritime.

But the Pentagon glossed over the threat of the “Phony Fleet”, only granting the force a few measly paragraphs in the back of the report.

Given China’s record, the dismissal of China’s maritime shock troops is inexplicable.

China’s conventional navy is small because China uses it’s “Phony War Fleet” to fight.

Working from an expansionist-minded playbook and backed by China’s over-hyped economic reputation, China’s belligerent “wolf warrior” diplomats and China’s formidable long-range strike forces, China’s “Phony War Fleet” is not phony at all.

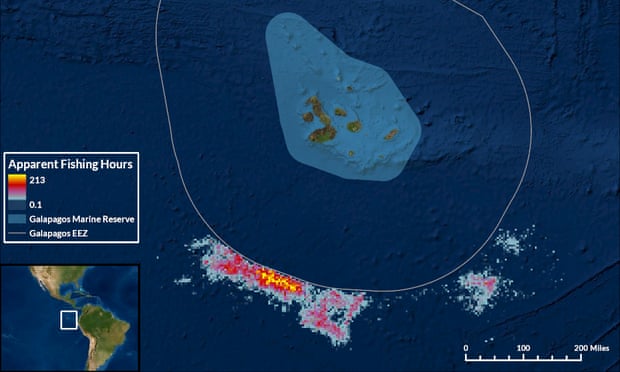

China’s enormous unconventional naval force might be dismissed as a “Phony War Fleet” by the Pentagon, but it is a clear and present danger anywhere from the Galapagos to Africa.

Outside of potentially Turkey, China’s “Phony War Fleet” is the only maritime force in the world capable of massing and sweeping aside established maritime order.

These are colonization-oriented shot troops, built for one thing—preying on the global maritime commons.

And while the Pentagon dreams of a low-cost robotic surface fleet, building up the reputation of China’s pipsqueak conventional Navy to get it, China’s massive “Phony War Fleet” gets a relative pass.

China’s small conventional Navy is only set to hold whatever advanced positions China’s “Phony War Fleet” can grab.

China’s “Phony War Fleet” is the present threat, and Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s low-cost robots can do little to stop it.

China’s Conventional Navy Is Puny:

Given the extensive maritime threats on China’s maritime periphery, the conventional Chinese Navy remains a coastal defense sideshow, poorly-sized to contend with the big and modern navies that surround much of China’s coast.

In the First Island Chain alone, the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force boasts a fleet of some 150 modern vessels.

Despite some oddly defeatist talk from some DC thinktanks, Japan maintains a formidable force of almost 30 destroyers, two pocket aircraft carriers, and one of the most modern undersea fleets in world.

Japan’s eight 10,000 ton-range Kongo, Atago and Maya class heavyweight destroyers can easily go toe-to-toe with China’s planned set of eight over-hyped but likely nuclear-armed Type 055 Renhai class cruisers.

South Korea’s green-water fleet is nothing shabby either, and Korea’s vast array of frigates, corvettes and patrol vessels can easily rebuff China’s mass of small conventional escorts.

America, even without the help of nearby friends, still outmatches China’s conventional Navy.

Of the forces arrayed in China’s 350-unit “battle force”, the Pentagon included 86 missile patrol boats.

Most of these patrol boats are 60 tiny, 220-ton missile-carrying catamarans, Type 022 Houbei class missile patrol boats.

America doesn’t even bother to count vessels of this size.

The U.S. Navy’s 13 pint-sized 336-ton Cyclone Class (PC-1) patrol craft outweigh China’s Type 022 patrol boats, yet the U.S. Navy refuses to include the Cyclones as part of America’s battle fleet.

And, while the Cyclones are mixing it up in the Persian Gulf and catching smugglers in the Caribbean, the Type 022’s are not out roaming the high seas.

The pint-sized catamarans are tough on their crews, and even if these patrol craft evolve to become “optionally unmanned” platforms, their endurance is very limited.

The Type 022s are only useful off islands, bases and other areas where China has sufficient support infrastructure in place.

China’s fearsome-seeming numbers were also bulked up by some 49 modern Jiangdao class Type 056/056A corvettes.

Type 056s comprise a second set of pint-sized, limited-mission, 1500-ton patrol vessels, half the displacement of an old American World War II-era Gearing class destroyer.

These corvettes boast a Littoral Combat Ship-sized crew, which, in America’s case, “was barely able to meet the Navy’s underway watch requirements and struggled to maintain qualified security teams while the ship was in port.”

These are simply vessels for imposing Chinese sovereignty in waters near any base China is lucky enough to establish.

On the amphibious side, much of China’s 52-ship fleet of tank and medium landing ships listed in the Pentagon’s report are obsolete and need replacing.

Certainly, if economic conditions permit, China’s conventional fleet is set to grow over time.

The report’s hyperventilation over how “China has already achieved parity with—or even exceeded—the United States” in shipbuilding is old news.

But, again, other countries have a vote here.

In 2019, South Korea outbuilt China by tonnage, with Japan and Italy following behind.

So while there are a lot of things worth worrying about in China’s military modernization, China’s conventional Navy looks awfully undersized and coastal—too small to fight, but ideal for securing and colonizing outposts that China’s expeditionary “Phony War Fleet” has already grabbed—snatched from a timorous international community that is, quite likely, too frightened by the Pentagon’s constant overestimation of the conventional Chinese “threat” to resist.

Fear China’s Sovereignty-Grabbing “Phony Fleet”

China’s massive “Phony Fleet” of low-end integrated maritime forces is well worth fearing.

But somehow, the Pentagon gave both the Chinese Coast Guard and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia a mere three paragraphs apiece.

That is rather light coverage for a set fast-growing forces that, time after time, have been at the center of China’s maritime colonization efforts.

It is growing in both numbers and size.

“Since 2010,” goes the report, the Chinese Coast Guard “fleet of large patrol ships (more than 1,000 tones) has more than doubled from approximately 60 to more than 130 ships”.

That’s a significant threat.

To compare, the U.S. Coast Guard has only about seventy ships of more than 1,000 tons.

The report fails to even attempt to quantify China’s burgeoning Maritime Militia, dismissing it even though this force has directly confronted U.S.

naval vessels, seized territory and led one provocation after another.

It’s the pointy edge of China’s maritime spear, and yet, the Pentagon refuses to offer any in the way of substantive analysis.

The Pentagon report fails to justify the growth in both number and size of these two coordinated fleets.

Civilian sources like Ian Urbina of Slate.com offers better analysis of China’s globe-spanning and highly-subsidized fleet of 200,000 to 800,000 aggressive, militarized fishing boats.

China already operates sovereign floating sea—bases for their fishing flotillas, but the evolution of Maritime Militia and Chinese Coast Guard units to long-endurance, out-of-area operations is a significant development, worth more than a few sentences.

It suggests that China’s “Phony” force will, in the coming years, be used in an expeditionary fashion, coordinating the irresponsible despoiling of shared maritime commons with unilateral grabs of maritime territory.

Only a big and unified armada of manned, boarding-ready Coast Guard-like ships can stop China’s “Phony War Fleet.”

A lawless “Phony War Fleet” bent only upon maritime mayhem and industrial-sized colonization will fail only if it is constantly confronted and discomfited.

Until a robotic surface fleet can do the delicate and dangerous work of constant confrontation, managing a relentless tempo of visit, board, search and seizure missions, Mark Esper’s effete fleet of robot surface ships will do little to stop China’s creeping colonization of the global maritime.

Links :