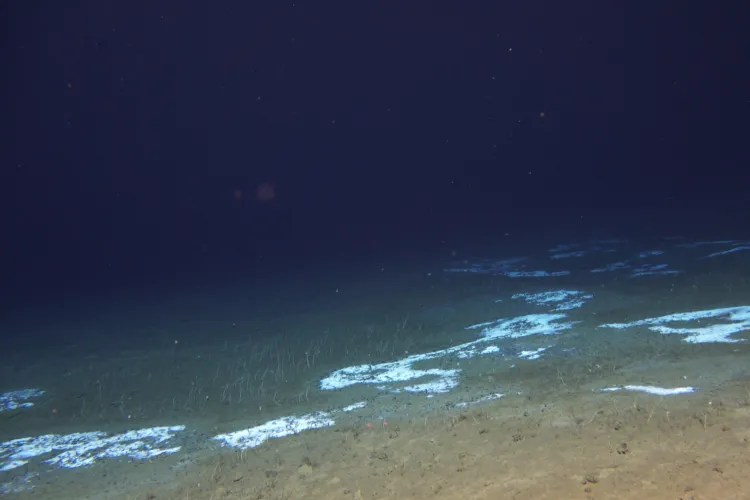

In OCEAN With David Attenborough, cameras captured what it looks like on

the seabed when a supertrawler's enormous net is unleashed.

Image credit: OCEAN With David Attenborough

From IFL Science by Rachael Funnell

Fishing has been a vital source of protein and nutrients for humankind for millennia, but as the years have gone by, we’ve gotten a little bit too good at it.

Ships now operate at sea trailing nets behind them at sizes that would blow the mind of the earliest fishers.

To be honest, their enormity is even hard to comprehend in the modern era.

Supertrawlers are massive industrial fishing ships that themselves are pretty huge.

Supertrawlers are massive industrial fishing ships that themselves are pretty huge.

They can be over 100 meters (328 feet) long, but that’s child’s play compared to what’s happening under the surface.

According to the Sussex Dolphin Project, the fishing net of a supertrawler can be 10 times the length of the ship itself at around a kilometer (0.6 miles) long.

According to the Sussex Dolphin Project, the fishing net of a supertrawler can be 10 times the length of the ship itself at around a kilometer (0.6 miles) long.

If you’re struggling to get your head around that, it’s roughly the equivalent of 14 jumbo jet planes, or three Eiffel Towers laying down.

In the case of bottom trawlers, this method of fishing entails dragging a chain or metal beam along the seafloor.

In the case of bottom trawlers, this method of fishing entails dragging a chain or metal beam along the seafloor.

It forces anything it disturbs into the net behind and destroys coral communities that can take decades to recover, adversely affecting biodiversity.

The visceral, heart-wrenching footage featured in the clip is the first time the process of bottom trawling was filmed in such high quality and the immense scale of trawling’s destruction revealed.

This destructive fishing method occurs daily across the globe; as Attenborough says in the clip, “very few places are safe from this.”

Iron chains bulldoze across the seabed, leaving trails of devastation in their wake that are visible from space.

Attenborough reveals that trawlers, often on the hunt for a single species, discard almost everything else, remarking, “it’s hard to imagine a more wasteful way to catch fish.”

An area almost the size of the Amazon rainforest is trawled every year, with the same places being trawled repeatedly, without the chance to recover.

Only by revealing this footage to the world and exposing what’s happening beneath the surface can people start to truly understand the impact on marine life.

“I've been working on marine conservation science for over 35 years, and we did the research that showed that bottom trawling, by churning the sediment on the sea floor, produces carbon dioxide emissions that are on the scale of global aviation every year,” marine ecologist Enric Sala, Executive Producer and Scientific Advisor on OCEAN, and National Geographic Explorer, told IFLScience.

“I have seen the bycatch on the deck of trawlers, but like everybody else, I had never seen what the trawl does underwater.”

“We had all this info, all this data that hits the brain, but this hit me in the guts. Being at the level of the net and seeing all these poor creatures trying to escape the net, that's something that nobody else had seen. What the film does so powerfully is that now people can see for themselves, right? It's not about believing one side or another. People can see for themselves, and they can make up their minds about this practice.”

These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry.

“We had all this info, all this data that hits the brain, but this hit me in the guts. Being at the level of the net and seeing all these poor creatures trying to escape the net, that's something that nobody else had seen. What the film does so powerfully is that now people can see for themselves, right? It's not about believing one side or another. People can see for themselves, and they can make up their minds about this practice.”

These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry.

Dutch-owned trawler FV Margiris, the world's second-biggest fishing vessel, shed more than 100,000 dead fish into the Atlantic Ocean off France, forming a floating carpet of carcasses that was spotted by environmental campaigners.

The spill, which happened in 2022, was caused by a rupture in the trawler's net, said fishing industry group PFA, which represents the vessel's owner.

In a statement, the group called the spill a "very rare occurrence."

The French arm of campaign group Sea Shepherd first published images of the spill, showing the ocean's surface covered by a dense, layer of blue whiting, a sub-species of cod, which is used by the industry to mass-produce fish fingers, fish oil and meal.

Sea Shepherd France said it doubted the incident was an accident.

Lamya Essemlali, head of the campaign group in France told Reuters her NGO was inclined to believe the fish were deliberately discharged.

"The EU regulation has been implemented so that we can reduce the non-selective fishing methods because it's very demanding, time-consuming and costs money for a fishing vessel to go back to port and unload the bycatch, and then go back at sea," she explained.

This bycatch can include numerous animals that aren’t the target species, ranging from small animals to creatures like turtles, sharks, and dolphins.

With fishing windows stretching for hours at a time, surviving long enough to be released isn’t a guarantee.

Trawling practices have adapted in recent years to try and address the issues of bycatch and sustainability.

These include cameras that can alert skippers when the wrong animals get trapped in the nets and enable them to pull the nets back up when the target species isn’t there.

A new approach also uses “flying doors” that are dragged just above the seabed, instead of across it.Concerns remain, however, as traditional trawling continues to be rife in areas of the ocean that are meant to be Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

In the UK, Greenpeace reported that 26 supertrawlers collectively spent 36,918 hours fishing in 44 MPAs between 2020 and early 2025 – but under the current government legislation it’s legal to do so, as bottom trawling is permitted in 90 percent of UK MPAs.

Such practices have a knock-on effect for the environment, but also for fishers.

Such practices have a knock-on effect for the environment, but also for fishers.

The negative impact on biodiversity means there’s fewer fish to catch, and trawling itself replaces more selective methods of fishing that generate more jobs and have a lower environmental impact.

The worst enemy of fishing is overfishing, not protected areas.

Enric Sala

Enric Sala

The good news is that the ocean has made a strong case for its ability to bounce back.

Just look at Papahānaumokuākea, one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world the proved large-scale marine protected areas for migratory species can work.

The marine conservation area gave yellowfin tuna a safe place to reproduce, and as they spread, we saw a boost in yellowfin tuna in surrounding areas of 54 percent.

It really is as simple as more fish means more fish, for everyone – including fishers.

“These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry,” said Sala.

“These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry,” said Sala.

“The worst enemy of fishing is overfishing, not protected areas. Protected areas are key to the future, and the industry. These areas are key to replenish the rest of the ocean and ensure that we have fish to catch and eat into the future.”

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Trawler 14 times the size of UK fishing boats is plundering ... / Supertrawlers 'making a mockery' of UK's protected seas / Fishing industry still 'bulldozing' seabed in 90% of UK marine ... / Tackling illegal fishing in western Africa could create ... / Huge bank of dead fish spotted off French Atlantic coast

Dadonghai Beach in Sanya, Hainan's southernmost city and a popular tourist destination.

Dadonghai Beach in Sanya, Hainan's southernmost city and a popular tourist destination.

A 2020 satellite image of a submarine entering a cave at East Yulin Naval Base.

A 2020 satellite image of a submarine entering a cave at East Yulin Naval Base.

A degaussing pier, built in 2008, minimizes the magnetic signature of vessels.

A degaussing pier, built in 2008, minimizes the magnetic signature of vessels. Time-lapse images depicting the development of Linghsui Air Base over 10 years.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of Linghsui Air Base over 10 years.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of the PLA Rocket Force base on Hainan.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of the PLA Rocket Force base on Hainan.

Clusters of tube worms.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Clusters of tube worms.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS Collections of microbes at the bottom of a trench in the Pacific Ocean.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Collections of microbes at the bottom of a trench in the Pacific Ocean.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS