Longtime Shippan resident and recreational sailor David Tunick has been preparing for most of his life, and particularly over the past three years, for a trip he plans to make this spring.

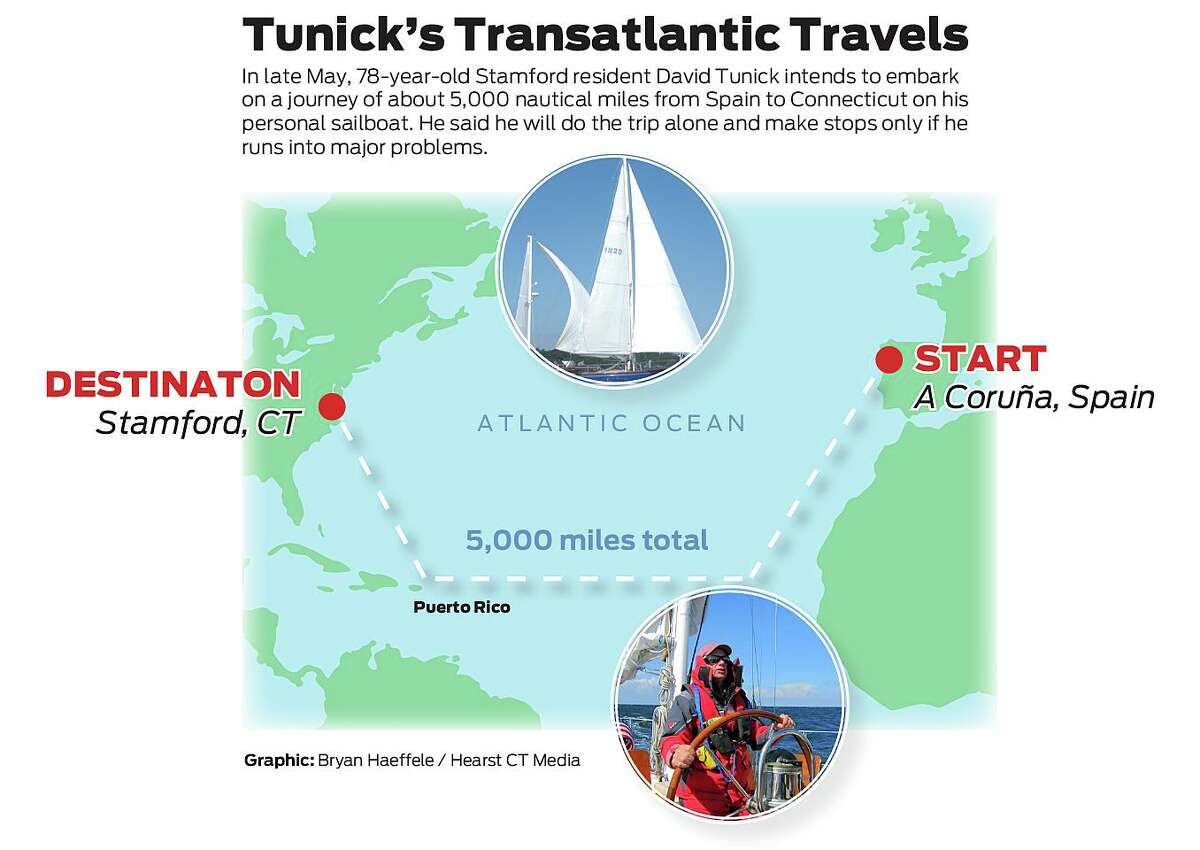

In late May, the 78-year-old intends to embark on a journey of about 5,000 nautical miles from Spain to Connecticut on his personal sailboat.

He said he will do the trip alone and only make stops if he runs into major problems.

“I love being alone out in the ocean,” Tunick said, especially at night under the stars and moon.

“I mean, I love having guests when we're coastwise — whether it's Cape Cod or Sweden or Norway or, wherever, Spain. I love having guests and sharing the experience. But in the ocean, I do like to be alone.”

It won’t be the first time Tunick has “singlehanded.”

He said he has taken solo trips for more than 40 years, including to Bermuda, Maine and across the North Sea.

Tunick sailed alone from Connecticut to England about 20 years ago.

That was a 22-day voyage.

He said he is expecting the trip back to the United States to take five to seven weeks because of the route.

Tunick, a New York art gallery owner and Stamford Yacht Club member, said he is in “great shape” and walks four to six miles a day.

Nevertheless, in the past three years, he said he has seen “every specialist under the sun” — including a pulmonologist, a cardiologist and an orthopedist — and had dental work done as well because “you don’t want to have to pull your own tooth” out on the water.

He’s even had his gallbladder removed, eliminating any possibility of having to deal with gallstones, he said.

Tunick has also been getting his well-used, decades-old sailboat, Night Watch, ready for the journey.

In recent years, the generator and engine have been rebuilt and the mast has been repaired

Last summer, he took the 55-foot vessel on a shakedown cruise from the Netherlands to Spain to see if there were any problems he needed to address.

Left: David Tunick works on the mast. Right: Night Watch sits in storage in a boatyard in Spain. Contributed by David Tunick

His family does have some concerns about him doing the trip, he said, but “they know I’ve done it before and they know that I’m OK at it.”

On board, he will have medical supplies, plenty of food — including pasta, canned meat and farm fresh eggs — a tracking device and a communication system.

He will be in regular contact with a meteorologist.

David Tunick poses at the Stamford Yacht Club in Stamford, Conn. Monday, Feb. 21, 2022. The 78-year-old intends to embark on a journey of about 5,000 nautical miles from Spain to Connecticut on his personal sailboat this May.

Tyler Sizemore / Hearst Connecticut Media

As for sleep, he said he puts his head down for one-and-a-half to two-and-half hours at a time then gets up to check on the boat.

But if he is in an area where he may cross paths with other boats, he takes power naps, with a timer waking him up every six to eight minutes.

On deck, he always wears a harness and tethers himself to his boat.

On the off chance the tether breaks and he goes overboard, he has a long, yellow line trailing behind the boat with a lightweight plastic container attached to the end that he could try to grab.

Clockwise: David Tunick standing at the helm, Night Watch racing in Denmark, Tunick in Sweden, and Night Watch at the Isle of Skye in Scotland.

Contributed by David Tunick

Tunick said he is passionate about boating safety — and has strict rules for when people are aboard his boat.

One of those rules: “Once we leave a dock, we leave a mooring, we haul anchor, you must be wearing a life preserver,” Tunick said.

“I don’t care how calm a day it is, how hot a day it is. I don’t care what the conditions are. Even if there’s no wind, you’re wearing a life preserver on my boat.”

Is he ever afraid when he is on a solo trip?

“I think that a little bit of fear is a good thing because it helps to keep you alert,” he said.

“It's really all about the preparation.”

Another question Tunick said he is often asked is: “Don’t you get bored? How can you stand being by yourself the whole time?”

“I’ve never really minded,” he said. “There’s always something to do — to fix, to check, to write in the log, to try to get some sleep, to cook dinner, to do the dishes.”

And one of the upsides of being alone: No one sees when he makes a mistake.

“I don't think of myself as a great sailor,” Tunick said.

“I'm a careful sailor, but I'm not a great, great sailor. And so I do make mistakes. And I like very much the idea of self-reliance and the accomplishment of achieving a passage and doing it correctly and properly.”

Something is bound to go wrong on a trip of more than 1,000 miles, he said, “and you have to have the wherewithal to fix it yourself.”

Left: The bow of Night Watch. Right: David Tunick at the Stamford Yacht Club. | Contributed by David Tunick | Tyler Sizemore / Hearst Connecticut Media

Tunick said he has “always been crazy about the water.” He recalled going with his father and uncles on power boats from Greenwich Harbor to Island Beach, where they would fish or swim. His uncles even had a model boat made for him — though it sank as soon as they put it into a pond at Bruce Park.

His first exposure to sailing was at camp.

Then, when Tunick was about 20 years old, he bought his first boat with a partner, splitting the $300 cost.

It was a 19-foot day racer with an open cockpit and no cabin, but he said he preferred to use it for cruising.

Sometimes he and a friend would take the boat out on Long Island Sound, sail to Oyster Bay or Huntington Bay, sleep in a sleeping bag on the beach and sail back the following day.

“I love just being on a boat,” Tunick said.

“I race around every day in New York in my day job. So when I'm out there, I don't want to have that feeling that I must be somewhere a tenth of a mile before somebody else or two minutes before somebody else.”

He later bought the boat that he has now owned for close to 40 years: a Sparkman & Stephens-designed, Abeking & Rasmussen-built vessel with an aluminum hull.

“There's no place I'd rather be, if not in my own house, than floating around on that boat,” he said.

Surface ocean warming appears to be speeding up global currents, reconstructed here from satellite and ship readings.

Surface ocean warming appears to be speeding up global currents, reconstructed here from satellite and ship readings. Researchers at Alaska's LeConte Glacier in 2016.

Researchers at Alaska's LeConte Glacier in 2016.

Erden Eruç arrived in Guam on February 12th Saturday after a 6,000-mile journey from Crescent City with a brief pit stop in Hawaii.

Erden Eruç arrived in Guam on February 12th Saturday after a 6,000-mile journey from Crescent City with a brief pit stop in Hawaii.