A 13th-century depiction of the world as a circle divided by into three continents, Asia, Europe, and Africa.

From Atlas Obscura by Genevieve Carlton

For some, they were an obstacle.

For others, they were an opportunity.

According to medieval mapmakers, the world was made up of three continents ringed by narrow bodies of water.

When the voyages of Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, and Ferdinand Magellan uncovered continents previously unknown to Europeans, this posed a major problem for those cartographers.

But these explorers did not just stumble upon uncharted land—they also became aware of expansive stretches of ocean around the world.

Jerusalem is in the center, surrounded by Europe, Asia and Africa.

For the first time, Europeans were confronted with the realization that they lived on a blue planet, with 71 percent of the Earth’s surface covered by water.

The narrow strips of blue on medieval mappae mundi—also known as

T-O maps, which showed the earth as a T centered on Jerusalem—were suddenly dwarfed by unimaginably vast oceans.

Stories about the European discovery of the New World are ubiquitous, but stories about the discovery of so much new water are much more rare.

For explorers, these oceans were dangerous obstacles.

Attempting to traverse them could quickly turn deadly, as the sailors on Magellan’s expedition learned when only one of their five ships—and 18 of the original 280 crewmen—returned to Spain in 1522.

Antonio Pigafetta, one of Magellan’s surviving men, described this first Pacific Ocean crossing, which took three months and 20 days, in a report.

He

wrote, “We only ate old biscuit reduced to powder, and full of grubs, and stinking from the dirt which the rats had made on it when eating the good biscuit, and we drank water that was yellow and stinking.”

Claudius Ptolemy, 13th Century world map

The oceans also posed a problem for mapmakers.

Reports from explorers deviated wildly from pre-Columbian perceptions of the world’s water, as evidenced in mappae mundi.

The 1475 world map in Lucas Brandis’s

Rudimentum novitiorum captures this older outlook on the world.

Asia, at the top of the map, represents one hemisphere, while wedges depicting Europe and Africa sit in the bottom half of the world.

The map was not intended to be representative; instead it focused on a Christian ordering of space with Jerusalem at the world’s center.

The world’s territories appear as hills, and in Europe, rulers sit atop them, with the pope in Rome shown holding a gold cross.

Asia and Africa, less well known to 15th-century Europeans, have more fanciful illustrations, including a pair of dragons, a burning phoenix, and a man-eating demon chasing his victim while clutching his severed arm.

On the map, the Mediterranean separates Europe from Africa and the rivers Don and Nile mark the divide between Asia and its neighbors.

Yet on this particular map, these bodies of water are marked by thin black lines and nothing more.

The only water seems to flow from the four great rivers at the top of the map, which represents the Garden of Eden’s Earthly Paradise.

A 1475 woodcut world map, published in Rudimentum novitiorum.

The discovery of massive bodies of water forced mapmakers to devise creative solutions.

One of the earliest strategies was to shrink the oceans.

Here, mapmakers borrowed from Columbus himself, who minimized his trans-Atlantic voyage by claiming that the crossing took only 33 days.

However, Columbus only counted from the Canary Islands to the Indies, omitting the 37 days spent traveling from Spain to the Canaries, which included repairs on two of his three ships.

Cantino planisphere (1502)

One of the earliest maps to show the New World, the 1502 Cantino planisphere, shrunk the Atlantic by showing Flores Island, the westernmost of the Azores, just slightly west of the jutting coast of Brazil, when in fact it is several degrees of longitude east of the Brazilian coast.

Battista Agnese world map (1544)

Battista Agnese, a Genoese mapmaker who produced at least 100 hand-drawn atlases for wealthy patrons, also narrowed the Atlantic in his 1544 world map.

Agnese drew only 10 degrees of longitude between Brazil’s furthest east point and Africa’s furthest west, nearly halving the actual distance of over 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles).

These cartographic manipulations consistently under-measured the Atlantic, minimizing the distance between the Old World and the New.

Sixteenth-century mapmakers also invented massive “undiscovered” continents to fill the oceans.

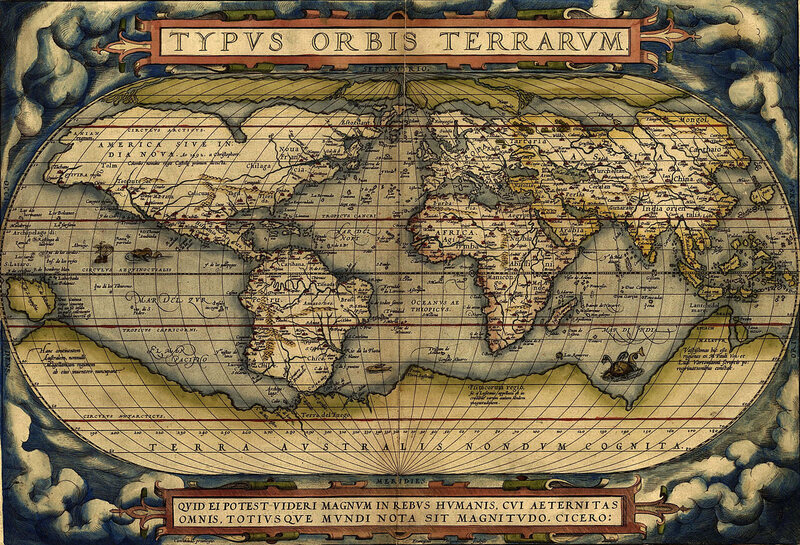

Two of the most famous maps from the 16th century, Abraham Ortelius’s 1570 world map in his atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, and Gerhard Mercator’s 1569 world map, (which introduced the Mercator projection) rely on this approach.

Produced less than a hundred years after the Rudimentum novitiorum, Ortelius’s map shows a completely transformed globe.

The shapes of the world’s continents, recognizable to our contemporary eyes and now divided by the grid of latitude and longitude, are arranged with

north at the top, a convention that only emerged in the 16th century.

The least familiar part of the globe is its southern stretches, which Ortelius labels “Terra Australis Nondum Cognita,” or southern land not yet known.

1604 copy of 1602 Kunyu Wanguo Quantu

Both the Ortelius and Mercator map admitted that the world’s oceans were vastly larger than those shown on any pre-Columbian map, but both also hypothesized a massive southern continent to “balance” the landmasses north of the equator.

Mercator made this explicit in 1595, when he

wrote, “it was necessary for such a continent to exist below to Antarctic Pole, which … would balance the other lands.” Europeans were so certain that this continent existed that Australia, first spotted by Europeans in 1606, took its name from the Latin term for Terra Australis.

These imagined continents did not just multiply the Earth’s land—they also limited the disturbing vastness of the world’s oceans.

Gerard De Jode Universi Orbi seu Terreni Globi (1578)

Other cartographers embraced the ocean’s blank canvas in a different way: by emphasizing just how empty it was.

In addition to minimizing the size of the Atlantic in his beautifully-colored maps, Agnese painted the land a rich green, depicting the mountains, rivers, and lakes that dotted the territory.

On the land, water is drawn in brilliant blue, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of California are colored red, a convention borrowed from mappae mundi.

The ocean, by contrast, was largely blank, the untreated vellum standing in for water.

Agnese did scatter a few islands throughout and used the blank space to highlight Ferdinand Magellan’s route as he circumnavigated the globe.

But his map implies that Magellan did not discover anything notable in the ocean; rather, the ocean was an emptiness between “real” places, defined by the absence of land rather than containing anything worth recording.

Agnese’s unknown land, or terra incognita, which also faded into blank vellum, was visually identical to the explored oceans, perhaps hinting that the ocean was ultimately unknowable.

"A Complete Geographical Map of all the Kingdoms of the World" (坤輿萬國全圖),

the first Chinese world map, 1602

But the seeming blank space of the ocean signified more than peril and emptiness—it also posed an opportunity for enterprising mapmakers.

Blank spaces on the map could be filled with promotions for the map’s creator or his hometown.

The French royal cosmographer and mapmaker André Thévet manufactured not one but two fictional Thevet Islands in the Atlantic in the 1580s.

Similarly, in a

1558 book with an accompanying map, Nicolò Zeno, a Venetian nobleman from a flagging family, alleged that his familial predecessors, Nicolò (his namesake) and Antonio Zeno, had landed on the invented island of Frisland and led voyages in the North Atlantic that discovered the New World in 1380, over a century before Columbus’s Genoa or Vespucci’s Florence could claim the glory.

And on his 1560 world map, Paolo Forlani, one of Venice’s most active mapmakers, used the wide oceans to promote Venice by sprinkling the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans with Venetian galleys, clearly not designed for transoceanic voyages.

The ships not only filled the water, but they also proclaimed Venetian dominance in an era when Venice had already lost the race to colonize distant territories.

Mapmakers also explored a range of design techniques to fill the oceans.

Giovanni Lorenzo D’Anania’s 1582 map of the North Atlantic not only populated the waters with imaginary islands, but also filled the sea with dark dots and large labels for the land, minimizing the impression of blankness.

In his 1566 map of North America, Forlani similarly peppered the Atlantic with islands both real and invented, expanded the size of North America, and dotted the waters on his engraving to avoid the impression that the oceans were simply blank.

He also made the Pacific much smaller than the Atlantic, placing the island of Japan halfway between North America and Asia.

Map of the Southern hemisphere, 1593 by Gerard de Jode

These mapmakers and the explorers who crossed the newly found oceans saw the water both as an obstacle, separating Europeans from their destination and posing countless dangers, and as an opportunity.

A blank space on a map let a mapmaker reinvent himself, much like pirates who roamed the seas, by manufacturing islands or adding flourishes to promote his city.

And when mapmakers signed their works, they almost always did so in the ocean.

Links :

.jpg/1280px-Cantino_planisphere_(1502).jpg)

.jpg/1280px-Kunyu_Wanguo_Quantu_(%E5%9D%A4%E8%BC%BF%E8%90%AC%E5%9C%8B%E5%85%A8%E5%9C%96).jpg?1509619164405)