Saturday, December 5, 2020

Friday, December 4, 2020

Book review : Melville’s whale was a warning we failed to heed

The killing in the 1830s of Mocha Dick, a giant sperm whale said to attack whaling ships with premeditated ferocity.

The killing in the 1830s of Mocha Dick, a giant sperm whale said to attack whaling ships with premeditated ferocity.Mocha Dick was an inspiration for Melville’s “Moby-Dick.”

Credit... Alamy

In 1841, while aboard the whaler Acushnet, Herman Melville met William Chase among another ship’s complement.

William lent Melville a book by his father, Owen Chase: “Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.” Melville had read Jeremiah Reynolds’s violent account of a sperm whale “white as wool,” named — for his haunt near Mocha Island, off the coast of Chile — Mocha Dick.

It’s unknown what led Melville to tweak Mocha to “Moby.” Good thing he did, and that Starbuck was the name he gave his first mate rather than his captain.

Otherwise the novel would follow Starbuck’s obsession with a Mocha.

Owen Chase gave Melville his climax: As Essex’s boats were harpooning female sperm whales, a huge male, around 85 feet, rushed and holed the 88-foot ship, twice.

No whale had ever sunk a ship.

“The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later recalled.

He initially planned a book about whales and whaling.

Reynolds helped supply Melville with a more Stygian idea, by exhorting his men to attack Mocha Dick as “though he were Beelzebub himself!” — a demon rather than a whale.

Yet Moby Dick is neither whale nor demon, but a white prop contrasting with the demonic Captain Ahab, the tormented tormentor, the malignant, abused abuser of authority and of men.

Ahab’s bias is personal and color-based.

A white whale becomes a blank pincushion for Ahab’s thrusting mania as Melville shades pages with his madness.

Yet — and this was absolutely astonishing for its time — Moby Dick becomes the ultimate asserter of reason.

In self-defense the whale delivers justice.

And never dies.

Ahab isn’t merely symptomatic; through his ability to steer men into complicity — and their inability to see it — he becomes contagious, truly dangerous.

“Moby-Dick” is called a great American novel.

Perhaps it’s the first great global novel.

Melville broke through American myopia, vanishing over many horizons, rubbing shoulders with apostates, seeing civility in savages, savagery in the civilized and ruinous obedience to mad tyrants.

Melville’s years on ships sowed what his biographer Newton Arvin called “a settled hatred of external authority.”

[For the social distancing edition of an annual marathon reading of “Moby-Dick,” volunteers are recording performances from home.]

By the 1840s, having ventured half the world away from America, Melville cast a frigatebird-like perspective on the American character’s deepest congenital malignancy, then called Negrophobia.

In the early 19th century, sperm whale hunting was never far from slave trading.

Thomas Beale’s 1839 “The Natural History of the Sperm Whale” included this telling dedication to the British shipowner Thomas Sturge: “Your character may be estimated by the incessant efforts you have made to liberate the Negro from the condition of the slave.”

On docks and decks humans of varied skin shades and breathing one another’s sweat in close company tended whale-boiling caldrons and looked one another in the eye.

Light-skinned men could feel trapped and dark men could taste freedom, surviving, sometimes drowning, together.

Melville’s ever-philosophical narrator, Ishmael, asks: “Who ain’t a slave? Tell me that.” From a world he experienced as spherical from atop ships’ masts, Melville perceived a sea-level humanity, embracing and celebrating the latitudes and longitudes of human variation, now termed diversity.

When Ishmael finds himself compelled to share a blanket at the sold-out Spouter Inn, he declares, “No man prefers to sleep two in a bed.” But he settles in, waiting for his mysterious South Seas roommate who, he’s informed, is peddling a shrunken head on the streets of New Bedford.

Queequeg’s appearance terrifies Ishmael mute.

But after things equilibrate, Ishmael reconsiders: “For all his tattooings he was on the whole a clean, comely looking cannibal … a human being just as I am. … Better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.”

In the morning Ishmael wakes to find Queequeg’s arm “thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner.

You had almost thought I had been his wife.” Now there’s no panic.

Eventually Queequeg rouses and, by signs and sounds, makes Ishmael understand that he’ll dress and leave.

“The truth is, these savages have an innate sense of delicacy,” Ishmael editorializes.

“It is marvelous how essentially polite they are.

… So much civility and consideration, while I was guilty of great rudeness.” Reflecting on Queequeg’s tatted visage, he concludes: “Savage though he was, and hideously marred about the face — at least to my taste — his countenance yet had a something in it which was by no means disagreeable.

You cannot hide the soul.

… Queequeg was George Washington cannibalistically developed.”

Mates now for life, they find a ship, but Queequeg is barred; he’s not Christian.

Ishmael fast-talks: Queequeg, like “all of us, and every mother’s son and soul of us,” belongs to “the great and everlasting First Congregation of this whole worshiping world.

… In that we all join hands.” Impressed by Ishmael’s impromptu sermon, the recruiter allows their marks; they’ll board the Pequod, a ship Melville has named, he reminds us, for a famed tribe of Massachusetts natives, already extinct.

Nearly two centuries ago, Melville showed us how easy it is to welcome as our own the touches of others, their equivalent colors, customs and beliefs; their journeys, their transitions.

And to remember those who, unwelcomed, suffered.

How much could have been avoided, and embraced, had we heeded.

Melville feverishly scribbled a diagnosis, prognosis and prescription for the human condition.

We are all Ishmael the ingénue and Starbuck the pragmatist and Ahab the maniac, stuck on a ship driven by winds we cannot predict, helmed by a mind not fully comprehensible, whose compulsions we don’t control.

The world is an elusive whale; we might choose coexistence or destruction.

And though we do not decide the outcome, the hands on those oars are ours; each stroke invites consequences.

And lest we overlook the obvious: The men went equipped to do harm in their quest for — oil.

If we are all Ishmael and Starbuck and Ahab, caught in our collective addiction, the whales exemplify a counterculture, a way of living weightlessly, of not draining the world that floats them.

It’s no coincidence that Leviathan, the sperm whale, is Melville’s chosen vehicle.

No other candidate qualifies.

Ahab could have chased a fire-breathing dragon.

But to face real quotidian madness we must have at stake real blood and real will on both sides.

Only this creature — the largest with teeth on the planet — comes to us as quickened flesh and immortal metaphor, tangling us with our own pursuits, profane, bleeding, sacred, free.

Only Leviathan could do it.

Could win.

So one wonders about those who’ve turned the book aside — as, in college, I did.

How does one fare, having failed to be forewarned about our inner Ahabs or the risks of being led into complicity with madness, uncounseled on the wisdom of rejecting the obsessive quests that the world’s pulpits condone and its ports reward.

“Moby-Dick” is only partly about madness; it’s equally about banality.

Herman Melville’s haunting inquiry — “whether Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc” — returns to me again while every whale in every ocean returns to share our air in seas we’re warming and thickening with plastic.

“If ever the world is to be again flooded, like the Netherlands, to kill off its rats,” Melville mused, “then the eternal whale will still survive, and … spout his frothed defiance to the skies.” But the warming that will erode the contours of Florida and New York, Houston, Hong Kong and Bangladesh will make life difficult for whales, too.

They, and all beings, as the naturalist Henry Beston wrote, are “caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.” Mesh by knotted mesh, it’s a net we have woven, perversely, by unweaving the web of life.

Melville tried to warn us.

Thursday, December 3, 2020

State of the art in multibeam echosounders

From Hydro by Huibert-Jan Lekkerkerk

The Evolution of a Bathymetric Workhorse

Although the single beam echosounder is still in use, it has over the last 25 years gradually been replaced with new and less expensive multibeam echosounder (MBES) systems.

And, although some side-scan sonar (SSS) systems also offer bathymetry, the MBES is the go-to system when it comes to bathymetry today.

MBES technology has gone through an evolution rather than a revolution in recent years.

In this article, we focus on the current state of the art for this bathymetric workhorse.

The Multibeam Echosounder

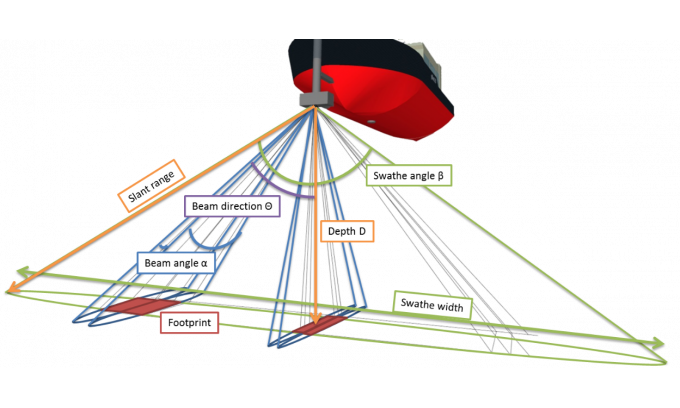

The main function of an MBES is to detect a number of depths along a swath of bottom.

To obtain these depths, the transducer sends out a pulse of sound that is reflected off the bottom and received by an array of transducers in a certain angular sector or swathe.

The system has a single transmit beam and a number (often 256) of receive beams.

The receive beams are formed on reception (and not, as some think, on transmission).

The swathe angle varies per system but is generally somewhere between 120° and 170°, giving swathe widths on the bottom in the order of 3.5 to 25 times the water depth.

Most multibeam echosounders are ‘shallow-water’ MBESs, with ranges between a few tens of metres and a few hundreds of metres.

A modern shallow-water MBES has a weight of a few kilograms up to tens of kilograms and can be installed on a surface vessel, ASV, AUV or ROV.

Although large and heavy special deepwater versions with ranges up to full ocean depth are also available, the ‘basic’ MBES is described below.

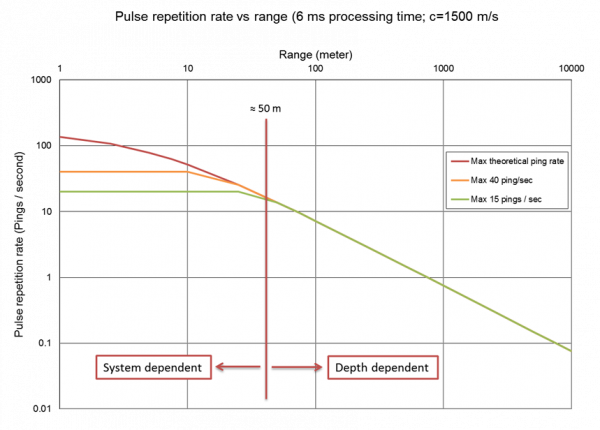

The final data density is defined by the number of beams (depths) and the ping rate, or the number of swathes that the MBES can measure per second.

The ping rate depends on the water depth, but can be as high as 60 pings per second in shallow water.

Accuracy

For nautical charting, the Special Publication 44 of the IHO sets the standard for sounding accuracy to which an MBES should adhere (together with the other sensors).

Some countries, and especially the offshore and dredging industry, do not find the S44 standards strict enough and impose their own accuracy standards on the work to be performed.

For the MBES to meet these standards, it not only needs to give full bottom coverage (sounding density) but also to measure each depth point with a minimum accuracy.

That accuracy depends both on the local situation and, more specifically, the sound velocity and the pulse length of the system.

Where in the past the transmitted signal was a ‘continuous wave’ (CW), a modern MBES can often also transmit what is called an FM or CHIRP (Compressed High Intensity Radar Pulse) signal.

The main advantage of the CHIRP is a longer range with better range resolution.

For a CW type MBES, the range resolution is defined by the pulse length of the signal, whereas for a CHIRP type MBES the range resolution is defined by the bandwidth of the signal, allowing longer pulses and therefore more power to be transmitted.

For a high frequency, shallow-water FM MBES, the range resolution is sub-centimetre for short ranges, allowing high accuracy for the sounded depths.

Frequency

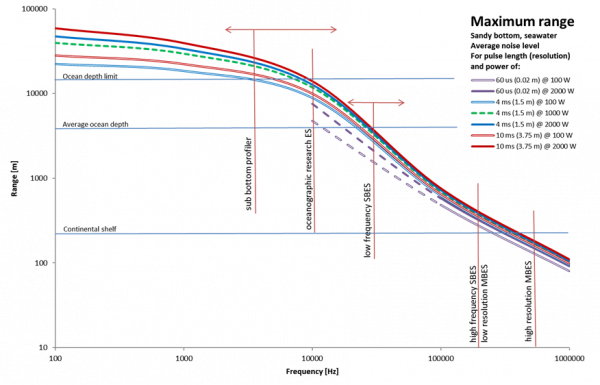

The capabilities and dimensions of any acoustic system are mainly defined by physics.

Underwater acoustics tell us that a high frequency will have a smaller range than a low frequency system.

However, a high frequency system can, at a given size, produce a smaller beam angle than a low frequency system.

Also, frequency dictates whether the system can penetrate the top layer of the sea bottom or will be reflected by it.

Finally, the frequency defines the smallest possible pulse length or bandwidth.

As can be seen, beam angle, size and range are all a function of frequency and counteract each other.

As such, there is no ideal frequency.

For highly detailed, close-range bathymetry, a high-frequency system will give the best results in a relatively small form factor.

For full ocean depth bathymetry, a low frequency needs to be chosen; if a small beam angle is then required the transducer will become large (and heavy).

In general, shallow-water MBESs operate at a frequency between 100 and 700kHz, which reflects off the top of the sea bottom but generally does not penetrate it.

To counteract frequency limitations, most manufacturers now offer shallow-water MBESs that are frequency-selectable.

That is, the MBES can be tuned to a specific frequency in the range of 100–700kHz.

Of course, the above remains true and the specifications of the MBES therefore change with a different frequency.

Multi-frequency and Multi-ping

Some manufacturers allow the user to not just select a single frequency but to use multiple frequencies simultaneously.

Although all the previous limitations still hold, using multiple frequencies can reduce the amount of noise encountered.

So, rather than not having some (high frequency) depths, these data points can be filled in using lower frequency data (although with a larger footprint and thus showing less detail).

Another option for especially deepwater MBES is the use of multi-ping.

In this situation, two to four pings are transmitted at slightly different angles simultaneously.

This counteracts the long travel times of the signal in deep water and allows for greater coverage without gaps at higher survey speeds.

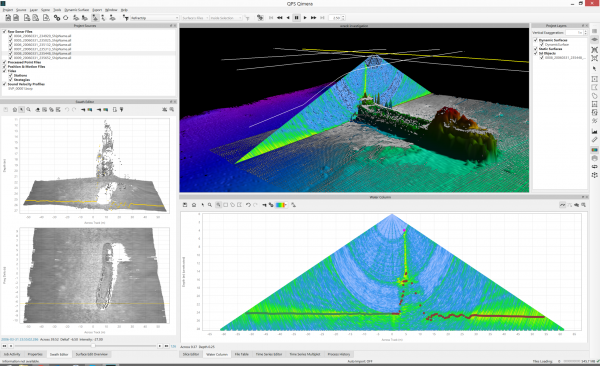

Water Column Data

A traditional MBES measures a single depth per beam per ping.

In general, the ‘first depth strong enough to be detected’ will result in the depth displayed.

Less strong depths that may be closer to the multibeam are not detected.

Also, a strong reflector close to the transducer may give a depth rather than the weaker bottom below it.

Many modern MBES systems circumvent this limitation by offering water column data as an option.

With this technique, the water column of each beam is divided into a number of ‘bins’.

The MBES now looks for a return within each bin for each beam for each ping.

This allows the MBES to measure multiple reflections and thus create 3D images of objects in the water column (or to see the bottom through, for example, vegetation).

Some manufacturers even support multi-frequency in combination with water column data, allowing even more objects to be positively detected.

As can be deduced, especially with many beams, multi-frequency and a high ping rate make the amount of data gathered enormous.

To compensate, the water column data is often compressed to make it manageable.

Despite this, the data volumes (and thus the time spent processing) are still large.

Backscatter is the amount of signal returning from the bottom.

Depending on the type of material, more or less signal will be received thus allowing object and bottom classification.

Most modern MBES systems have the option to receive backscatter data together with the depth information and show an SSS-like image.

Some manufacturers combine the backscatter data with both water column and multi-frequency capabilities, allowing even more information to be collected.

The advantage of combining backscatter with water column data is that objects in the water column can be better identified.

The combination of backscatter with multi-frequency is especially useful for bottom classification.

As materials can react differently to different frequencies, measuring the backscatter at different frequencies but at the same moment in time can give classification algorithms better information to work with.

SSS vs Multibeam Echosounders

With the backscatter option on the MBES, a common question is whether an SSS is still required.

As described in an earlier article on SSS technology, the brief answer is that it is.

The difference between MBES backscatter and a true SSS is that the MBES will provide one backscatter value per beam, whereas the SSS will provide an almost continuous signal, thus giving a higher resolution.

So, an MBES provides at most around 1,024 backscatter points per swathe, whereas an SSS has a continuous signal.

However, the MBES data may be more than enough for a general classification.

If, however, more detail is required, it is advisable to use an SSS.

Other Options

Besides the options described above, manufacturers offer additional options in their systems.

An example is a dual head set-up.

With this option, a much larger swathe can be created with swathe angles up to 240°, allowing surface to surface measurements for inspection work.

The dual head option is often used in pipeline inspections.

Some manufacturers also offer a pipeline mode, where a small sector beneath the transducer gives highly detailed information (at a high frequency).

Another option often offered is the integration of an Inertial Motion Unit (IMU) with the MBES.

This is often advertised as not needing any calibration, although most manufacturers mean that there is no additional calibration required between the MBES and the IMU.

Performing an MBES calibration will also give the IMU calibration parameters.

Sometimes ignored is the fact that the IMU also plays a role in the positioning system.

This means that, even though the values can be obtained from the MBES calibration, they still need to be entered into the survey software to compensate for any positioning offsets.

Wednesday, December 2, 2020

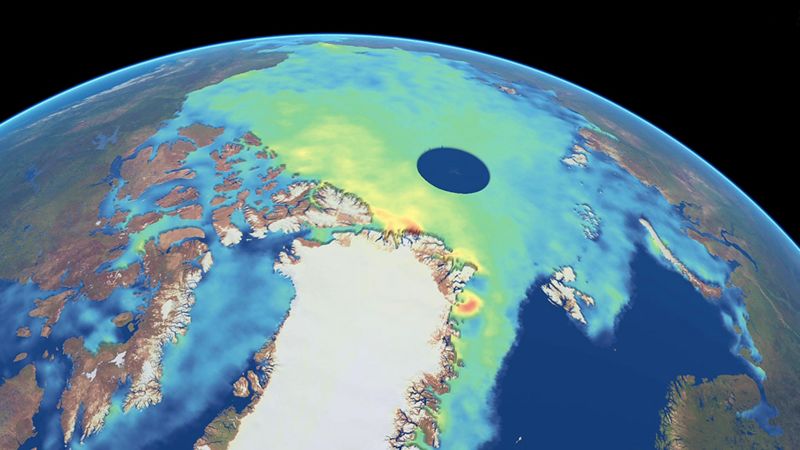

Polar scientists wary of impending satellite gap

From BBC by Jonathan Amos

There is going to be a gap of several years in our ability to measure the thickness of ice at the top and bottom of the world, scientists are warning.The only two satellites dedicated to observing the poles are almost certain to die before replacements are flown.

This could leave us blind to some important changes in the Arctic and the Antarctic as the climate warms.

The researchers have raised their concerns with the European Commission and the European Space Agency.

A letter detailing the problem - and possible solutions - was sent to leading EC and Esa officials this week; and although the US space agency (Nasa) has not formally been addressed, it has been made aware of the correspondence.

At issue is the longevity of the European CryoSat-2 and American IceSat-2 missions.

These spacecraft carry instruments called altimeters that gauge the shape and elevation of ice surfaces.

They've been critical in recording the loss of sea-ice volume and the declining mass of glaciers.

image captionArtwork: CryoSat-2 (top) and IceSat-2 (bottom) will hopefully last until mid-decade

What's unique about the satellites is their orbits around the Earth.

In contrast, most other satellites don't usually go above 83 degrees.

The worry is that CryoSat-2 and IceSat-2 will have been decommissioned long before any follow-ups get launched.

CryoSat-2 is already way beyond its design life. It was put in space in 2010 with the expectation it would work for at least 3.5 years.

IceSat-2 was launched in 2018 with a design life of three years, but with the hope - and expectation - it can operate productively deep into the decade.

"Without successful mitigation, there will be a gap of between two and five years in our polar satellite altimetry capability," the scientists' letter states."

The only satellite replacement currently in prospect is the EC/Esa mission codenamed Cristal.

Industry has started work on the spacecraft but it won't launch until 2027/28, maybe even later because full funding to make this date a reality is not yet in place.

Dr Josef Aschbacher, the director of Earth observation at Esa, said his agency was working as fast as it could to plug the gap.

"This is a concern; we recognise it," he told the BBC. "We've put plans in motion to build Cristal as quick as we can. Despite Covid, despite heavy workloads and video conferences by everyone - we have gone through the evaluation... and Cristal was kicked off in early September."

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNAS Aimage caption An option for Europe?

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNAS Aimage caption An option for Europe?Just over 10% of the near-600 signatories to the letter are American scientists.

Dr Thomas Zurbuchen, the head of science at Nasa, is not being sent the letter because it is primarily aimed at European funders - and most of the signatories are European.

He said he was hopeful any polar gap could be plugged or minimised.

"I think there are multiple options at this moment in time that we can deploy to that end, in partnership or otherwise," he commented.

One of those solutions in Europe would be to run a version of Nasa's IceBridge project.

This was an airborne platform that the US agency operated in the eight years between the end of the very first IceSat mission in 2010 and the launch of IceSat-2 in 2018.

An aeroplane flew a laser altimeter over the Arctic and the Antarctic to gather some limited data-sets that could eventually be used to tie the two IceSat missions together.

There are many who think a European "CryoBridge" is the most affordable and near-term option to mitigate the empty years between CryoSat-2 and Cristal.

The cost of manufacture of the airborne radar altimeter could be accomplished for perhaps €5m (£4.5m), scientists believe, but its design and fabrication would likely take two years.

The signatories to the letter sent to the EC and Esa include leading scientists using CryoSat and IceSat data, the president of the International Glaciology Society, and lead authors on the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which prepares the authoritative state-of-the-climate reports for world governments.

Tuesday, December 1, 2020

400 years on, the Pilgrims get a reality check

After finding no suitable home, the Pilgrims sailed to Plymouth Bay, ferried ashore in small groups, and settled in the remains of a Native American village.

Photograph By Detroit Publishing Company, Library Of Congress

From the signing of the Mayflower Compact to the landing at Plymouth Rock, the grade-school story of the Pilgrims doesn’t quite square with the facts.

The good people of Plymouth, Massachusetts, had big plans for 2020, the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival in New England.

The town’s nonprofit living history museum—known since its 1947 founding as Plimoth Plantation—had spent considerable time and some expense rebranding itself Plimoth Patuxet Museums, to more accurately represent the link between the Pilgrims and the Native American tribe whose village they occupied.

More than $11 million had been invested in restoring Mayflower II, the reproduction ship that has floated in Plymouth Harbor since 1957.

Tens of thousands of spectators were expected for the renovated ship’s triumphant return from dry dock, including a rendezvous with Boston’s 223-year-old U.S.S.

Constitution, and an escort of Native Americans paddling dugout canoes.

Millions were expected to attend the biggest summer-long party Plymouth had ever seen.

Then, last spring, COVID-19 came and ate all the birthday cake.

Then again, the story of the Pilgrims’ early years in Massachusetts and their relationship with the Indigenous people they met there has always been fraught with unexpected twists.

The Europeans found their foothold in the ruins of a village emptied by the ravages of plague.

Barely surviving their first winter, they feared being overrun by the Native Americans they saw peering at them from the forest—only to find in them an unlikely military and trade partner.

And through it all, in every direction, the land was stained by treachery, bloodshed, and betrayal.

For the hundreds of thousands of annual visitors to the Plimoth Patuxent Museums, those hard truths can be difficult to square with the traditional grade-school narrative many of us grew up with—of benevolent Pilgrims and amiable Indians seated around a big Thanksgiving picnic table.

But the real story is, if a bit more complicated, no less human.

New discoveries have revealed not only the extent of conflict between the two cultures, but also the surprising levels of social intimacy they shared.

But it was a far cry from the hundreds of thousands of visitors the town was expecting before COVID-19 kept them away.

Stormy beginnings

Despite their haloed image, the Pilgrims were a decidedly motley crew.

Staunch Protestant Puritans, they had been forced into exile in the Netherlands around 1607 for resisting King James’s Church of England.

But the strait-laced refugees were doubly unhappy in the Netherlands, which then as now was a fairly freewheeling party scene.

Luckily, King James was anxious to populate the new North American colonies, so he let the Pilgrims sail there to practice their renegade religion undisturbed.

The voyage would be financed by investors, and in return the Pilgrims would send furs and other goods back to England for sale.

After a few false starts, the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, England, on September 6, 1620.

For 65 miserable days the huddled passengers endured storms, sickness, and even the births of two children, a pair of boys named Oceanus Hopkins and Peregrine White.

Weather forced them north of their intended destination along the Hudson River, then part of the British colony of Virginia.

Finally, on November 9, land was sighted: the tip of Cape Cod.

“We loosed from Plymouth having been kindly entertained and courteously used by divers friends there dwelling,” wrote Pilgrim leader Edward Winslow.

Unlike Virginia, the land that spread before the Pilgrims had, as far as Carver knew, no formal charter from King James, and thus no effective law.

He became alarmed when some of the non-Puritans among them gleefully began to anticipate becoming a law unto themselves.

Quickly, the Pilgrim leadership drafted a rudimentary constitution to “combine our selves together into a civil body politick”—which would, through democratic process, enact “just and equal laws…for the general good of the Colony.”

“This is almost certainly not the room where the Mayflower Compact was signed,” says Richard Pickering, chief historian for Plimoth Patuxet Museums.

We are standing in a relatively large cabin at the back end of Mayflower II.Countless paintings depict finely dressed Pilgrim fathers gathered in just such a cabin and seated, Last Supper-like, around a large table, wielding feathery quills as they sign their document of self-government.

“First of all,” Pickering explains, “these were crew quarters, and the crew didn’t really even like the Pilgrims. All 102 of them were crammed onto the deck below this.”

In reality, the signing was probably more of an informal affair, Pickering says.

“The document was carried from person to person: ‘Here—sign this!’ There was also a bit of coercion involved. You weren’t getting off the boat until you signed.”

Coerced or not, the Mayflower Compact stands as a landmark document in North American history.

Although Native American tribes had organized into governments for centuries, the Pilgrims’ compact was the New World’s first written constitution of self-government by Europeans.

A tale of two rocks

Cape Cod curls like a flexed arm, its angry fist railing against the assault of New England winters.

At its apex stands Provincetown’s 110-year-old Pilgrim Memorial, a 250-foot tower commemorating the Pilgrim’s first landing nearby.

Incongruously based on the 14th-century Torre del Mangia in Siena, Italy, the monument looks as if its creators had somehow confused Thanksgiving with Columbus Day.

Atop its 116 steps and ramps, the New World of the Pilgrims comes into focus.

To the east, Atlantic surf pounds Cape Cod National Seashore.

Down the coast lies First Encounter Beach, site of the first face-off between the newly-arrived Pilgrims and the Wampanoag.

That initial meeting ended in a brief, ineffectual volley of arrows and gunshots.

It was the beginning of a complicated relationship that began in conflict, grew into a shaky political alliance, and finally devolved into open hostilities and centuries of mistrust.

Even today, the two sides are, in a sense, trying to work out their troubled shared history.

Some 32 miles west, outlined against the low afternoon sun, lies the Pilgrims’ ultimate destination: the protected natural harbor of Plymouth Bay.

The Pilgrims wrote about their adventures in exquisite detail, yet never once did they mention Plymouth Rock, traditional site of their second landing a few weeks after their arrival.

Not until 1741 did the elderly son of a Pilgrim bestow that honor on the modest boulder that now sits under a granite canopy on Plymouth’s waterfront.

So breathless was the schoolhouse lore of Plymouth Rock that, as a young boy on a New England vacation with my family, I fully expected to see a monolith the size of Gibraltar—only to discover a hunk of stone that resembled a big, gray beanbag chair.

Never a very large rock, the thing is today about one-third its original size, the rest having been chipped away by souvenir seekers.

Built to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Ma…

From Plymouth Rock I climb a steep concrete stairway up Cole’s Hill, a bluff overlooking Plymouth Bay.

Most years the hill rings with the laughter of tourists snapping selfies, but in truth there are few spots more mournful than this, a place long associated with death and despair.

Ascending this hill, the first Pilgrim expedition discovered a literal ghost town: a Native village, empty for three years or so.

Many of its huts were still populated by skeletal corpses of Patuxet who had been wiped out by a hemorrhagic disease—probably smallpox brought by earlier European traders.

Still, the grotesque site sat on an easily defensible hillside beside a rushing stream.

Despite its clearly awful history, the Pilgrims settled there, praising God for his provision.

But praise soon turned to mourning.

At the lip of Cole’s Hill stands a marble sarcophagus containing a mass of commingled bones—assumed to be those of the 52 Pilgrim men, women, and children who died of disease and exposure that first savage winter.

They’d been hastily buried on this site in the dead of winter, only to have their remains exposed following heavy rains in the late 1800s.

The melancholy spirit of Cole’s Hill deepens just a few feet away with a more modest monument, a plaque attached to a rock commemorating a “National Day of Mourning.” Each Thanksgiving, representatives of many Native American tribes gather here to remember, in the words of the plaque, “the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture.” (Today, traditional indigenous beliefs are a powerful tool for understanding COVID-19.)

The sadness of this place is palpable.

Sole survivor

After those initial burials on Cole’s Hill, the Pilgrims established a new cemetery higher in the hills, just beyond the wooden palisade they built around their settlement.

Burial Hill remains a quiet, tree-shrouded retreat, a relatively easy climb from the waterfront.

From its summit, through the trees and headstones, the sweeping view of Plymouth Bay and its barrier sand bars affirms why this made such a likely spot for defense from attack by sea.

The surrounding woods, however, were another story.

Turning south atop Burial Hill, I look toward another hill just across the narrow and fast-moving Town Brook.

For months in early 1621, Pilgrims stood where I’m standing and gazed across the creek, watching nervously as the concerned faces of Wampanoag tribe members stared back at them.

Then, on March 16, a Native American strode boldly through the gate of Plimoth, raised his hand, and greeted them in English.

His name was Samoset, and he’d learned the foreigners’ language from traders.

He returned with another Native American named Tisquantum, more commonly known as Squanto.

This man not only spoke perfect English, but years earlier he’d been kidnapped and taken to Europe as a slave.

Squanto had gained his freedom and returned to North America as a guide, only to learn that his misfortune had probably saved his life: He was, it turned out, a member of the Patuxet tribe, which in his absence had been wiped out by plague.

Now, the Patuxet’s sole survivor stood in the Pilgrims’ new settlement—built on the ruins of his dead family’s home.

(Related: Native American imagery abounds, but the people are often forgotten.)

With Squanto serving as translator, the Pilgrims negotiated a peace treaty with Massasoit, leader of the Wampanoag—a loose confederation of several area tribes, including the now-extinct Patuxet.

Most significantly, the two parties agreed to provide mutual defense—a bond that benefited both Massasoit, who was facing resistance from rivals, and the Pilgrims, who would have been helpless in the face of any concerted attack.

It was that treaty, in fact, that led to the fabled first Thanksgiving.

As the Pilgrims celebrated their first harvest in November 1621, they fired their muskets into the air.

Legend has it that Massasoit, fearing his allies were under attack, rushed to the scene with a group of warriors.

Relieved to discover all was well, the story goes, the group stayed for dinner.

More likely, Plimoth historian Pickering says, Massoit and his men, who were accustomed to hearing gunshots from military drills, dropped by on a diplomatic mission, bringing along five deer as a gift.

'This isn’t Disneyland'

As fall foliage erupts in yellows and reds, the Plimoth Patuxet Museum’s parking lot should be jammed with cars from every state east of the Mississippi.

Instead, a hundred or so vehicles, virtually all with Massachusetts plates, bunch near the entrance.

The limited numbers are no surprise.

Just to visit here from my home in Delaware I first had to fill out an online Massachusetts State Visitor’s Form and bring documentation of a recent negative COVID-19 test.

I’m greeted near the visitors center by Darius Coombs, a Wampanoag tribe member and a museum staffer for more than 30 years.

As I zip up my windbreaker against the fall chill, Coombs seems entirely comfortable in his traditional dress: moose hide moccasins and deerskin leggings, breechcloth and mantle.

Around his shoulders is draped a beaver pelt coat, worn with the fur facing in to capture and preserve body heat.

Over his arm hangs the skin of a black wolf.

Coombs leads me to a clearing with a pinwheel-shaped pattern staked out on the ground—the outline of what the Wampanoag call a snail house, first built in these parts some 12,000 years ago.

COVID willing, it will be built in time for next season’s visitors.

The museum’s reconstructed circa-1620 Wampanoag village, a scattering of bark-covered houses called wetu, sits on the shore of the Eel River.

By the water, a tribe member scrapes a mishoon, a dugout canoe, from a tree trunk.

Nearby, a massive 46-foot mishoon—carved from a seven-ton tree—lies nearly completed.

Like Coombs, all the skin-wearing workers here are Wampanoag.

“You can’t wear skins if you’re not Wampanoag,” he says.

“When we go hunting for these animals, we do a ceremony for them. You’re taking the animal’s life, so it becomes part of what we are. This is important to us. This isn’t Disneyland.”

I can’t help but notice that Coombs’s accent often carries echoes of his Boston childhood (“…paht of what we ah”).

When I suggest his speech would never pass muster in a Hollywood movie about Native Americans, he smiles at the memory of a documentary crew that recently asked his help making a film about Wampanoag children at the time of the Pilgrims.

He agreed, with one condition: “I told them they’d also have to show our children today—wearing jeans and sneakers and riding their bikes.

I don’t want kids to think our children only existed in the past.

They are here now, and they’re just like any other kids.”

A startling discovery

I am walking up The Street, as the one and only avenue in early Plimoth Colony was known.

The unpaved, eroded course is flanked by rustic timber houses with thatched roofs.

Behind many of them are small gardens, tended by men and women in period dress, diligently digging, hoeing, or pruning.

The original Street lies somewhere below the busy pavement of modern-day Plymouth’s Leyden Street.

This replica runs up a similar hillside three miles south of the original, through the middle of the reconstructed Plimoth Plantation.

Behind one house I spot a red-bearded man in a bright yellow smock, hard at work.

“I’m hoeing dung,” he cheerfully declares with a smile and a lilting British accent.

He tells me he is Edward Winslow, a signatory of the Mayflower Compact, three-time governor of the colony, and author of a seminal Pilgrim account, Good Newes From New England.

“We use this dung to fertilize our little garden beds,” he says.

“But in the fields, for the corn, we use fish, as the Indians showed us.

I would not wish to have enough animals to create enough dung to cover our corn fields!”

He chats animatedly about encouraging news from Jamestown and the death of King James.

I can tell he could go on all afternoon, but I’ve been told I’m free to ask the museum’s historical interpreters to break character and talk about their real selves—a radical departure from the museum’s strict stay-in-character rules.

Checking to make sure no other visitors are within earshot, I ask Edward Winslow to re-enter the 21st century.

The twinkle in his eyes remains, but the voice abruptly shifts from 17th-century English to modern-day suburban Bostonian.

A gala celebration in Boston Harbor had to be scrapped due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bernard explains he’s sprinkling his archaic language with a Worcestershire accent.

“I had a woman from England go into a full regional dialect with me,” he says.

“That was a personal win.”

Too soon, it’s time to let Joshua Bernard return to Edward Winslow.

“A pleasure,” says the 400-year-old Pilgrim.

He turns back to his dung pile.

As I exit through the broad opening in the replica palisade, I notice a loaf-shaped, bark-covered Wampanoag wetu house about 20 yards away.

New archaeological research suggests the house might belong much closer.

(A newfound survivor camp may explain fate of the famed Lost Colony of Roanoke.)

Digging at the foot of Burial Hill in 2019, a University of Massachusetts team discovered a line of dark soil that is almost certainly the remains of the colony’s original palisade—the first actual remnant of Plimoth ever found.

But the most exciting find was hard against the outside of that wall: the remains of what appears to be a Wampanoag tool-making site.

“Literally, these two cultures were living a few feet away from each other,” says Jade Luiz, curator of collections at Plimoth Patuxet Museums, where an entire gallery is given to a history of the Wampanoag and their interactions with the Europeans.

“That rewrites a lot of what we thought we knew about them.”

Baptized in blood

The Wampanoag showed the Pilgrims how to farm New England’s thin soil and also traded furs the Pilgrims desperately needed in order to pay their creditors back in London.

Beyond that, theirs was a relationship baptized in blood.

As part of their mutual defense agreement, the two groups fought side by side against Massasoit’s enemies.

Pilgrim leaders even lured two men from a rival tribe to a supposed private dinner—and promptly stabbed them both to death.

“Life was brutal,” says historian David Silverman, a professor of history at George Washington University and author of This Land is Their Land.

“If you walked into either the Plymouth colony or a Wampanoag village during the 1600s, the first thing you’d see at the entrance would be severed body parts and decapitated heads.”

He does not envy the stewards of Plimoth Patuxet Museums as they try to balance family-friendly experiences with cold-hearted history.

“Good history,” he says, “upsets everyone.”

The Pilgrim-Wampanoag alliance lasted about 50 years.

After the death of Massasoit in 1662, his son Metacom, also known as King Phillip, began to push back against European encroachment.

In the course of King Philip’s War, from 1675 to 1678, Native Americans raided more than half the European settlements from Connecticut to Maine.

The colonists responded by forming an armed militia, the first in colonial history.

In the end, the Europeans prevailed.

The systematic conquest of America’s Indigenous peoples had begun in earnest.

But is it wrong to memorialize that one bright moment when people of two very different worlds found a way to coexist?

“When you think about it, 50 years of peace is a pretty long time,” says Turner.

“Even though the alliance between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag was one of necessity and not of friendship, it’s nevertheless worth celebrating.”

Monday, November 30, 2020

Chinese manned deep-sea submersible gets rare look at deepest ocean depths, the Mariana Trench

From Science Times by Erika P.

In a live-streamed footage, China has broken its record for the deepest manned dive into the world's deepest oceanic trench. The Chinese submersible, named "Fendouzhe," or "Strive," descended on the seabed of Mariana Trench on Tuesday morning after one month of sailing from Hainan province in China.

The submersible dived an estimated 10,909 meters (35,790 feet) into the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean with three researchers on board, according to state broadcaster CCTV.

The recent dive has beaten its record by over 800 meters (2,624 feet) and missed out on beating the world record for the deepest dive in Mariana Trench, which was set by American undersea explorer Victor Vescovo.

He claims to have reached a depth of 10,927 meters (35,853 feet) last year in May.

This week, video footage from the underwater camera showed that the green and white Chinese submersible is moving through dark waters in the Mariana Trench surrounded by clouds of sediments as it touches down the seabed.

According to a report by Phys.org, China has conducted multiple dives of Fendouzhe earlier this month and landed on the deepest known point of the trench, which is the Challenger Deep, just a few meters higher than the world record of Vescovo.

For the first time, the world witnessed the first live video from Challenger deep as the Chinese submersible descends into the Earth's deepest oceanic trench.

Fendouzhe has robotic arms that it uses to collect biological samples and sonar eyes to identify its surroundings using sound waves.

Since it is carrying too much equipment, the engineers had to add a bulbous forehead or a protrusion that contains buoyant materials to keep its balance.

The country's goal aside from scientific exploration is to explore the abundance that is hidden in the deep ocean, said Ye Cong, the submersible's designer.

He told the state-run media that they need high-tech diving equipment to help better draw a "treasure map" of the deep part of the ocean.

In 2018, Japan did a remarkable discovery of rare earth resources on its small island of Minamitori in the Pacific Ocean where it is said that recoverable resources are 1,000 times more than on land.

Rare earths are used for the production of high-tech products like smartphones, missile systems, and radar, which is currently controlled by China, according to CNN. Its capital is working hard to retain its dominance in this industry, reaching a record-breaking quota in July that is as high as 140,000 tons (140 million kilograms).

That being said, China is participating in joint research and training with the International Seabed Authority, to train professionals on deep-sea technology and conduct further research on mining for rare earths found in the deep sea.

Fendouzhe is seen to set the standards for the future of deep-sea vessels of China.

But Zhu Min, one of the researchers, said that it would take two trials before the success of the submersible's mission is declared.

Links :