Nope. pic.twitter.com/DmCLIbgdbj

— Sven Henrich (@NorthmanTrader) October 27, 2022

Saturday, November 29, 2025

Friday, November 28, 2025

The Mary Celeste: 'A curiosity that has never been satisfied'

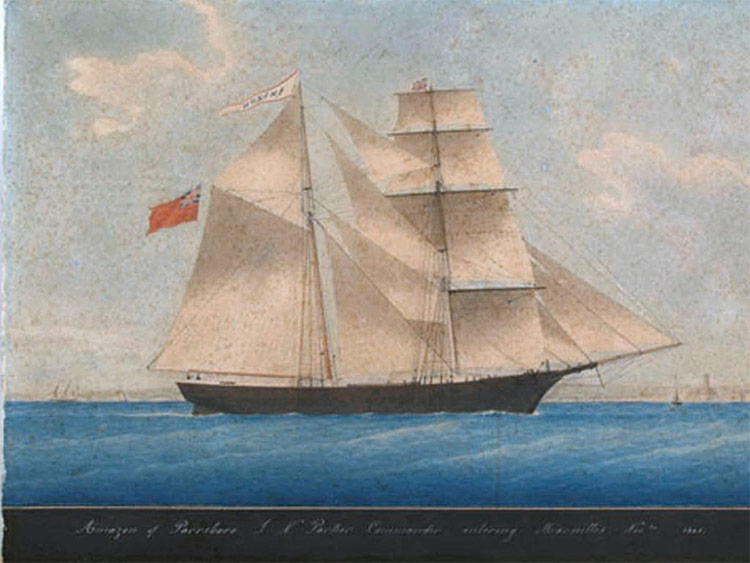

Mary Celeste in 1861, when she was known as Amazon

Mary Celeste in 1861, when she was known as AmazonFrom HistoryToday by Rhys Griffiths

The true story behind the much-mythologised ship and its vanished crew.

In 1884, the ‘phenomenally successful’ literary journal Cornhill

Magazine published, anonymously, J.

Habakuk Jephson’s Statement.

Purporting to ‘subjoin a few extracts’ from an article that appeared in the Gibraltar Gazette, it began:

In the month of December in the year 1873, the British ship Dei Gratia steered into Gibraltar, having in tow the derelict brigantine Marie Celeste, which had been picked up in latitude 38 degrees 40', longitude 17 degrees 15' W.

There were several circumstances in connection with the condition and appearance of this abandoned vessel which excited considerable comment at the time, and aroused a curiosity which has never been satisfied.

The Gibraltar Gazette is fictional, Marie a variation on Mary, and the discovery takes place a year late, but otherwise, the above represents a fairly accurate summary of fact: on December 4th, 1872 a small cargo ship carrying 1700 barrels of alcohol bound for Genoa from New York was found by the Dei Gratia adrift in the Atlantic ocean.

As is now well known, the Mary Celeste was completely abandoned.

Speculation as to what happened to its crew has been a renewable source of debate ever since.

From hereon in, however Jephson’s statement on the fate of the ship and its crew enters the realm of fiction and, arguably, has stayed there ever since.

It was the first work to be published in a major publication by Arthur Conan Doyle, most famous as creator of Sherlock Holmes and victim of the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

Most writers could only dream of creating such an legacy with their first notable work.

Conan Doyle’s sensational solution to the mystery (the culprit is a mutilated stowaway on a cutthroat jihad against all white men) captured public attention to such an extent that the British and American governments were prompted to respond with formal denials and official investigations.

In something approaching a self-fullfilling prophecy, the Statement created an interest in the Mary Celeste that has endured, unsatisfied, for well over 100 years becoming a genre in its own right.

Valerie Martin, author of the Mary Celeste’s most recent fictional outing included Conan Doyle as a character in The Ghost of the Mary Celeste (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2014), but lukewarm reviews of the book suggest that while the reading public is drawn to the mystery, they also like a satisfying conclusion.

Habakuk Jephson’s Statement.

Purporting to ‘subjoin a few extracts’ from an article that appeared in the Gibraltar Gazette, it began:

In the month of December in the year 1873, the British ship Dei Gratia steered into Gibraltar, having in tow the derelict brigantine Marie Celeste, which had been picked up in latitude 38 degrees 40', longitude 17 degrees 15' W.

There were several circumstances in connection with the condition and appearance of this abandoned vessel which excited considerable comment at the time, and aroused a curiosity which has never been satisfied.

The Gibraltar Gazette is fictional, Marie a variation on Mary, and the discovery takes place a year late, but otherwise, the above represents a fairly accurate summary of fact: on December 4th, 1872 a small cargo ship carrying 1700 barrels of alcohol bound for Genoa from New York was found by the Dei Gratia adrift in the Atlantic ocean.

As is now well known, the Mary Celeste was completely abandoned.

Speculation as to what happened to its crew has been a renewable source of debate ever since.

From hereon in, however Jephson’s statement on the fate of the ship and its crew enters the realm of fiction and, arguably, has stayed there ever since.

It was the first work to be published in a major publication by Arthur Conan Doyle, most famous as creator of Sherlock Holmes and victim of the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

Most writers could only dream of creating such an legacy with their first notable work.

Conan Doyle’s sensational solution to the mystery (the culprit is a mutilated stowaway on a cutthroat jihad against all white men) captured public attention to such an extent that the British and American governments were prompted to respond with formal denials and official investigations.

In something approaching a self-fullfilling prophecy, the Statement created an interest in the Mary Celeste that has endured, unsatisfied, for well over 100 years becoming a genre in its own right.

Valerie Martin, author of the Mary Celeste’s most recent fictional outing included Conan Doyle as a character in The Ghost of the Mary Celeste (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2014), but lukewarm reviews of the book suggest that while the reading public is drawn to the mystery, they also like a satisfying conclusion.

Jermoe de Groot, reviewing the book in History Today, described the book as ‘circling around the mystery without seeming to contribute anything purposeful’.

‘I was hoping for a titillating historical-fiction mystery about the real-life vessel Mary Celeste […] What I got was a fragmented and vapid tale about ... well ...

I'm not sure’, complained one reader reviewing the book online.

‘I was hoping for a titillating historical-fiction mystery about the real-life vessel Mary Celeste […] What I got was a fragmented and vapid tale about ... well ...

I'm not sure’, complained one reader reviewing the book online.

Mary Celeste (often misreported as Marie Celeste) was an American merchant brigantine that was found adrift and deserted in the Atlantic Ocean, off the Azores Islands, on December 4, 1872, by the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia.

She was in a disheveled but seaworthy condition, under partial sail, with no one on board, and her lifeboat missing.

The last log entry was dated ten days earlier.

She had left New York City for Genoa on November 7, and on discovery was still amply provisioned.

Her cargo of denatured alcohol was intact, and the captain's and crew's personal belongings were undisturbed.

None of those who had been on board—the captain and his wife, their two-year-old daughter, and the crew of seven—were ever seen or heard from again. Mary Celeste was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia and launched under British registration as Amazon, in 1861.

She transferred to American ownership and registration in 1868, when she acquired her new name, and thereafter sailed uneventfully until her 1872 voyage.

At the salvage hearings in Gibraltar following her recovery, the court's officers considered various possibilities of foul play, including mutiny by Mary Celeste's crew, piracy by the Dei Gratia crew or others, and conspiracy to carry out insurance or salvage fraud.

No convincing evidence was found to support these theories, but unresolved suspicions led to a relatively low salvage award. The inconclusive nature of the hearings helped to foster continued speculation as to the nature of the mystery, and the story has repeatedly been complicated by false detail and fantasy.

Hypotheses that have been advanced include the effects on the crew of alcohol fumes rising from the cargo, submarine earthquakes (seaquakes), waterspouts, attacks by giant squid, and paranormal intervention. After the Gibraltar hearings, Mary Celeste continued in service under new owners.

In 1885, her captain deliberately wrecked her off the coast of Haiti, as part of an attempted insurance fraud.

The story of her 1872 abandonment has been recounted and dramatized many times, in documentaries, novels, plays and films, and the name of the ship has become synonymous with unexplained desertion. In 1884, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story based on the mystery, but spelled the vessel's name as Marie Celeste.

This spelling has now become more common than the original in everyday use. The keel of the future Mary Celeste was laid in late 1860 at the shipyard of Joshua Dewis in the village of Spencer's Island, on the shores of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia.

The ship was constructed of locally felled timber, with two masts, and was rigged as a brigantine; she was carvel-built, with the hull planking flush rather than overlapping.

She was launched on May 18, 1861, given the name Amazon, and registered at nearby Parrsboro on June 10, 1861.

Her registration documents described her as 99.3 feet (30.3 m) in length, 25.5 feet (7.8 m) broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet (3.6 m), and of 198.42 gross tonnage.

She was owned by a local consortium of nine people, headed by Dewis; among the co-owners was Robert McLellan, the ship's first captain. For her maiden voyage in June 1861, Amazon sailed to Five Islands to take on a cargo of timber for passage across the Atlantic to London.

After supervising the ship's loading, Captain McLellan fell ill; his condition worsened, and Amazon returned to Spencer's Island where McLellan died on June 19.

John Nutting Parker took over as captain, and resumed the voyage to London, in the course of which Amazon encountered further misadventures.

She collided with fishing equipment in the narrows off Eastport, Maine, and after leaving London ran into and sank a brig in the English Channel.

She was in a disheveled but seaworthy condition, under partial sail, with no one on board, and her lifeboat missing.

The last log entry was dated ten days earlier.

She had left New York City for Genoa on November 7, and on discovery was still amply provisioned.

Her cargo of denatured alcohol was intact, and the captain's and crew's personal belongings were undisturbed.

None of those who had been on board—the captain and his wife, their two-year-old daughter, and the crew of seven—were ever seen or heard from again. Mary Celeste was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia and launched under British registration as Amazon, in 1861.

She transferred to American ownership and registration in 1868, when she acquired her new name, and thereafter sailed uneventfully until her 1872 voyage.

At the salvage hearings in Gibraltar following her recovery, the court's officers considered various possibilities of foul play, including mutiny by Mary Celeste's crew, piracy by the Dei Gratia crew or others, and conspiracy to carry out insurance or salvage fraud.

No convincing evidence was found to support these theories, but unresolved suspicions led to a relatively low salvage award. The inconclusive nature of the hearings helped to foster continued speculation as to the nature of the mystery, and the story has repeatedly been complicated by false detail and fantasy.

Hypotheses that have been advanced include the effects on the crew of alcohol fumes rising from the cargo, submarine earthquakes (seaquakes), waterspouts, attacks by giant squid, and paranormal intervention. After the Gibraltar hearings, Mary Celeste continued in service under new owners.

In 1885, her captain deliberately wrecked her off the coast of Haiti, as part of an attempted insurance fraud.

The story of her 1872 abandonment has been recounted and dramatized many times, in documentaries, novels, plays and films, and the name of the ship has become synonymous with unexplained desertion. In 1884, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story based on the mystery, but spelled the vessel's name as Marie Celeste.

This spelling has now become more common than the original in everyday use. The keel of the future Mary Celeste was laid in late 1860 at the shipyard of Joshua Dewis in the village of Spencer's Island, on the shores of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia.

The ship was constructed of locally felled timber, with two masts, and was rigged as a brigantine; she was carvel-built, with the hull planking flush rather than overlapping.

She was launched on May 18, 1861, given the name Amazon, and registered at nearby Parrsboro on June 10, 1861.

Her registration documents described her as 99.3 feet (30.3 m) in length, 25.5 feet (7.8 m) broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet (3.6 m), and of 198.42 gross tonnage.

She was owned by a local consortium of nine people, headed by Dewis; among the co-owners was Robert McLellan, the ship's first captain. For her maiden voyage in June 1861, Amazon sailed to Five Islands to take on a cargo of timber for passage across the Atlantic to London.

After supervising the ship's loading, Captain McLellan fell ill; his condition worsened, and Amazon returned to Spencer's Island where McLellan died on June 19.

John Nutting Parker took over as captain, and resumed the voyage to London, in the course of which Amazon encountered further misadventures.

She collided with fishing equipment in the narrows off Eastport, Maine, and after leaving London ran into and sank a brig in the English Channel.

There are some great pieces of mystery fiction set aboard ships.

The ‘framing’ device used by Conan Doyle might put readers in mind of later works like Stefan Zweig’s novellas Chess and Amok, or Bram Stoker’s Dracula where the count arrives at Whitby aboard a ghost ship in a case of reverse colonisation that would send titillating shudders through Victorian England.All the above titles were read voraciously by the reading public, arguably satisfying a hunger fanned by Conan Doyle with his popularisation of the Celeste story years before.

Worth noting, however, is that the impact of Conan Doyle’s story belies the fact that he lived in an age where the day’s biggest authors – HG Wells, Zweig, Robert Louis Stevenson – enjoyed the sort of mass readership that enabled them to shape public belief.

The Celeste myth was a product of a time when literary fiction was at its most powerful: it’s a matter of debate as to whether Conan Doyle’s modern day contemporaries could exert the same influence.

Worth noting, however, is that the impact of Conan Doyle’s story belies the fact that he lived in an age where the day’s biggest authors – HG Wells, Zweig, Robert Louis Stevenson – enjoyed the sort of mass readership that enabled them to shape public belief.

The Celeste myth was a product of a time when literary fiction was at its most powerful: it’s a matter of debate as to whether Conan Doyle’s modern day contemporaries could exert the same influence.

Links :

- Smithsonian Mag : Abandoned Ship: The Mary Celeste

- CBC : A N.S. ghost ship is fading from memory — 150 years after its crew disappeared

- AccuWeather : Could weather hold the secret to history's greatest ghost ship mystery?

- The Mary Celeste website

- The Telegraph : On this day in 1872: the Mary Celeste was found adrift in the Atlantic, inexplicably deserted

- The Guardian : The Ghost of the Mary Celeste by Valerie Martin – review

- NYT : The Ghost of the Mary Celeste by Valerie Martin – review

- WP : ‘The Ghost of the Mary Celeste,’ by Valerie Martin

Thursday, November 27, 2025

Correct the map: why the Mercator world map must be put to rest

Historic map and instruments.

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

From Democracy without borders by Olivia Gauvin

When you imagine a world map, what do you see? Is it the expansive oceans, the intricate coastlines, or the seemingly infinite land masses of Russia and Greenland? If you’re like most people, you probably know the Mercator projection — one of the most popular world maps used for educational and commercial purposes.

Though, what most people don’t realize is that this same world map studied in schools and displayed across the globe is startlingly wrong.

Due to the Mercator projection’s distortions, the world map as you imagine it may be entirely mistaken.

In an effort to address these distortions, Africa No Filter and SpeakUpAfrica launched the Correct The Map campaign one year ago to promote the use of a more proportional and equitable world map.

Their campaign calls on international organizations, corporations, and global citizens to retire the Mercator projection due to its misrepresentation of Africa’s true size.

And while such critiques against the Mercator projection have been raised for decades, the Correct The Map petition’s newest endorser is pushing for a change: the African Union.

In August, the AU Commission deputy chairperson Selma Malika Haddadi spoke to Reuters about the pressing need for the globally standardized use of a world map projection that more accurately depicts the African continent.

The African Union, Africa No Filter, and SpeakUpAfrica are thus reviving global awareness surrounding the Mercator projection’s distortions and its global consequences.

By promoting a proposed alternative map — the Equal Earth projection — the Correct The Map campaign is working to transform distorted perceptions of the African continent’s place in the world.

Mapping the distortions

In 1569, a German cartographer by the name of Gerarus Mercator published a ground-breaking world map projection.

The Mercator projection signaled a major breakthrough in nautical navigation because it preserved accurate angles for sailors, despite distorting the relative size of landmasses closer to the poles.

By the early 19th century, after innovations in marine shipping, the map projection swiftly grew in popularity alongside the expansion of global imperialism, trade, and migration.

Ultimately, the Mercator projection became the standard commercial and educational map across the globe, reifying an inaccurate physical image of our world.

An example of the Mercator projection, which enlarges regions near the poles.

Image: Wikimedia/Daniel R.

Strebe

Strebe

For example, the Mercator projection depicts the landmass of Greenland to be relatively equal in size to the African continent, but Africa in reality is 14 times larger.

The Arabian Peninsula, with an area of approximately 3.2 million sq km is depicted as a similar size to Brazil, with 8.36 million sq km.

Land masses which are further from the equator appear especially distorted, therefore having an unintentional proportional ‘shrinking’ effect on Africa and other areas.

Mapping the Earth’s three-dimensional surface onto a two-dimensional page will always include distortions.

A handful of maps have been developed over the years to directly address and correct Mercator’s distortions, such as the Galls-Peters projection and the Robinson projection, both of which also contain some shaping distortions.

However, the Equal Earth projection, published in 2018, successfully depicts “developing countries in the tropics and developed countries in the north with correctly proportioned sizes” in a visually pleasing manner.

This new map, according to the contributing scientists, is both a humanitarian cause and a scientifically well-balanced projection.

An example of the Equal Earth projection which is designed to show landmasses in their true proportions.

Image: Wikimedia/Daniel R. Strebe

Image: Wikimedia/Daniel R. Strebe

In addition to being equal-area throughout, the Equal Earth projection aligns with the mission of international activist networks in promoting greater fairness and integrity in the social sciences across the world.

For example, with over 3,700 signatories on their own website, Correct The Map is petitioning for the United Nations and the BBC to “adopt the Equal Earth projection in their data, reports, and materials that include world maps.” As it stands today, neither organization uses a proscribed map projection.

According to the United Nations’ Geospatial Network, the UN most frequently uses the Robinson projection due to its proportionality and fairness.

The BBC Sound recently produced a podcast episode exploring their corporation’s usage of the Mercator projection.

Further, while endorsing the Equal Earth projection themselves, it’s unclear as to whether the African Union has yet adopted it as their official map projection.

Promoting an Equal Earth

In light of these growing global movements advocating for the distribution and application of the Equal Earth projection, it is necessary to consider how any world map can meaningfully address the bias and exploitation that the African continent has borne.

Nonetheless, there is no question that distorted maps, like the Mercator projection, significantly muddle our capacity for adequately understanding land mass, environmental resources, borders and security, infrastructure, geopolitics and societies — particularly impacting perceptions and biases towards the Global South.

Thus, what is most significant about the mission of the Correct The Map campaign is not merely the corrected distortions, but the broader educational component.

Incorporating the Equal Earth projection into schools and educational initiatives across the world will empower students to finally envision their shared world in its real proportions.

In promoting the use of a more equitable and accurate map projection, the Correct The Map campaign continues to foster global citizenship perspectives and strengthen education worldwide.

For some, the continued use of the Mercator map reinforces the histories and legacies of exploitation and marginalization of the Global South.

By petitioning governing bodies and organizations to adopt the Equal Earth projection, Africa No Filter and SpeakUpAfrica are working together to decolonize the global depiction of physical space.

With the weight of the African Union behind them, the Correct The Map campaign is reigniting an international discussion about our most fundamental perceptions of size and space.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog :

Mercator projection : the Greenland problem /

Mechanics of map projections : the myth of Mercator /

World Mercator projection with true country size added /

Gerardus Mercator : father of modern mapmaking /

Advisory notice on "Web Mercator" /

African Union joins calls to end use of Mercator map that ... /

First NOAA nautical map in Mercator projection /

Princeton astrophysicists re-imagine world map, designing ...

Google Maps now has a "Globe" projection instead of Web ...

Why your mental map of the world is (probably) wrong /

Mapping the Oceans /

Nautical charts - how the most important navigational aid is ... /

Why maps are civilization's greatest tool /

Japan's 'Good Design Award' goes to this crazy accurate .../

These are the cleverest, weirdest mapping ideas ever ... /

Why modern maps put everyone at the centre of the world /

These antique maps showed how people saw the world. ... /

How 16th-century European mapmakers described the ... /

Nautical chart smarts /

Bizarre, enormous 16th-century map assembled for first time /

'The perfect combination of art and science': mourning ...

Wednesday, November 26, 2025

How secret underwater wiretapping helped end the Cold War

From PopMechanics by Matt Blitz

Secrets haunt the still-classified Operation Ivy Bells, a daring Cold War wiretapping operation conducted 400 feet underwater.

It's the summer of 1972 and the U.S.

is in the middle of pulling off the most daring, covert, and dangerous operation of the Cold War.

Only a few months before, the signing of SALT I (Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty) limited the number of nuclear missiles of the world's two largest superpowers.

Yet even with this well-publicized US/Soviet détente in place, a submerged American submarine rests mere miles from the Russian coastline.

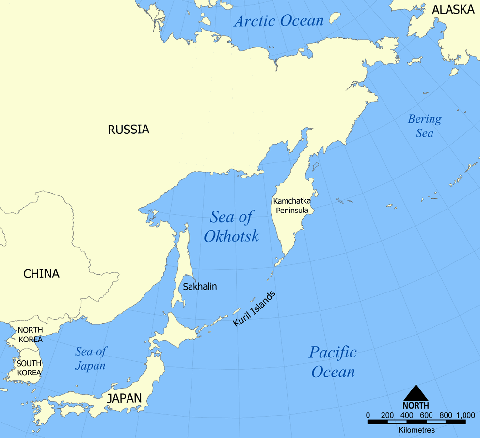

At the bottom of the Sea of Okhotsk, the U.S. nuclear submarine Halibutsilently listens to the secret conversations of the Soviet Union.

With the Kremlin completely unaware, Navy divers emerge from a hidden compartment (referred to as the "Bat Cave") and walk along the bottom of the sea in complete darkness, wiretapping the Soviet's underwater communications line.

America wiretapped this particular Soviet communications cable for maybe a decade or more—and many details remain classified.

It was the U.S.'s most ambitious wiretapping operation, until this point, in its entire history.

This was Operation Ivy Bells.

U.S. Navy / Darryl L. Baker

Shipyard model of the USS Halibut (SSGN-587), Nov.18, 1957.

Shipyard model of the USS Halibut (SSGN-587), Nov.18, 1957.

Battle Plans and Mistresses

Down below the sea surface, the intel is flooding in.

With the divers' taps in place, American communication techs onboard the Halibut gather a wide range of intelligence, from operational tactics to Soviet commanders' conversations with their mistresses.

But up on the sea surface, a storm is brewing.

As the angry sea rocks the sub, the still-working divers are trapped outside the vessel in the murky cold water.

Then, with a loud snap, the steel anchor lines break free.

The Halibut drifts upwards, in danger of exposing itself to the enemy.

"If (they) had gotten caught, [they] had every reason to belief that [the Soviets] would have blown [them] away," says Sherry Sontag, who co-wrote the 1998 book Blind Man's Bluff.

Quickly, Captain John McNish makes a rather unconventional decision: to flood the sub.

In a matter of seconds, the Halibut plops back down into the sea bottom's sandy muck.

The divers scramble back into their decompression chamber (used toprevent the "bends") and an international crisis is averted—at least temporarily.

Days later and after the storm subsides, the Halibut finally emerges from its watery depths.

The mission is a resounding success, and the sub is returning home with tapes of recorded Soviet Union voices discussing the secrets of a superpower.

As W. Craig Reed wrote in his book Red November, it was like the U.S. placing "a glass against the Soviet Union's wall to hear their every word."

Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum

USS Halibut, 1962.

USS Halibut, 1962.

What Lies Beneath

This sub mission was one of several that made up the still-classified Operation Ivy Bells.

It's not exactly a secret that the U.S.

and USSR launched a silent intelligence war, one that lasted for decades and likely continues to this day, even after the fall of the Soviet Union.

What made Operation Ivy Bells so unprecedented is the literal depths to which the U.S.

government would go to spy on its Cold War rival.

According to Sontag's book, it was Captain James Bradley who first considered the possibility of an underwater wiretapping operation.

A World War II and Vietnam War vet who had commanded ships in the heat of the battle, Bradley knew how to operate in close proximity to the enemy.

In 1966, he became the undersea warfare director in the Office of Naval Intelligence, where he came up with the idea that forever shifted the Cold War in America's favor.

In 1968, Bradley devised and led a mission that sent the Halibut into the Pacific in search of the Soviet sub K-129, lost due to an internal explosion during a routine patrol.

The Soviets' searched for months with little success, but they were missing an invaluable ally that aided the American quest: "the fish."

Built by Westinghouse Electric at an estimated cost of $5 million each, this was a two-ton underwater camera mounted inside a mini-sub, deployed while remaining tethered to the Halibut.

The fish hovered just above the ocean floor taking pictures.

"It was kinda like a sophisticated vacuum cleaner for your pool," Reed told Popular Mechanics.

While the covert mission to dredge up K-129 called Project Azorian was only a partial success, it proved the fish could capture images even in the dark waters of the ocean floor.

But the Halibut and the fish's next mission would be much more complicated—and dangerous.

Bradley believed an unencrypted telephone line connected Petropavlovsk's submarine base (near the tip of Kamchatka peninsula) to Russia's mainland, likely running under the Sea of Okhotsk.

Soviet cryptographers were notoriously backlogged and military officers needed fast communication between the Kremlin and Russia's most important naval base.

So, Bradley theorized, the Soviet's solution was to deposit a communications line so deep underwater and close to Russia's shoreline that no one could access it.

Or so they thought.

U.S. Navy/Gary Flynn

USS Halibut pushing its nuclear engines.

USS Halibut pushing its nuclear engines.

The Challenges Ahead—and Below

Three obstacles stood in Bradley's way.

First, the search area needed to be significantly narrowed to have any chance of finding the cables in 611,200 square miles of water.

According to legend, the solution came to Bradley one morning in his Pentagon office.

Daydreaming about his boyhood spent on the Mississippi River, Bradley remembered that there were signs near the shorelines warning boaters not to anchor due to utility lines at the bottom of the river.

He realized that if there were location signs like this in America, there surely would be in Russia as well.

He was absolutely right.

When the Halibut moved into the Sea of Okhotsk, they scanned the Siberian coast and found warning signs dotting its northernmost half, telling fisherman to avoid particular areas.

"The Soviets weren't trying to hide (the cables)," says Sontag,

"They had no idea we could get that close...that we could send divers walking on the bottom that deep...or that we had the technology to tap it. No one had conceived anything like this before."

Within days, the Navy had found what they'd been looking for.

Next, they needed to figure out how divers were going to go and stay that deep underwater for the several hours needed to complete the wiretapping.

The answer was helium.

Since the late 1950s, Navy Captain George F. Bond had been developing new methods, techniques, and gases that would allow divers to go deeper and stay submerged for longer.

While his infamous Sealab project was shut down after the death of a diver, Bond proved that certain gas mixes could work.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

Within days, the Navy had found what they'd been looking for.

Next, they needed to figure out how divers were going to go and stay that deep underwater for the several hours needed to complete the wiretapping.

The answer was helium.

Since the late 1950s, Navy Captain George F. Bond had been developing new methods, techniques, and gases that would allow divers to go deeper and stay submerged for longer.

While his infamous Sealab project was shut down after the death of a diver, Bond proved that certain gas mixes could work.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

U.S. Navy/Eric Lippmann

This U.S. Navy diver chiseling free deck plating from the sunken USS Monitor is an example of saturation diving, 2001.

This U.S. Navy diver chiseling free deck plating from the sunken USS Monitor is an example of saturation diving, 2001.

We land mammals breathe in a cocktail of gases every day that is around 80 percent nitrogen and 20 percent oxygen, with a few other garnishes thrown in.

When these gasses are compressed by water pressure, it causes nitrogen to build up in the blood.

This can be an extremely dangerous condition for humans that can result in nitrogen narcosis or decompression sickness, a fatal embolism if the diver does not decompress properly while ascending.

So instead, Ivy Bells substituted nitrogen for helium.

Helium has a lower molecular weight than nitrogen and leaves human tissue more rapidly, making it perfect for a diving technique known as saturation diving.

With the search completed and the human element solved, the last complication involved the mechanics of the tap itself.

To avoid shorting out the cable (and alarming the Soviets), the divers couldn't just open it up.

Instead, the wiretap had to work through induction.

The divers would need to place the tap by wrapping a connector around the comm line and then feed it into a three-foot-long reel-to-reel tape recorder.

"We were using technology that is so far advanced from the civilian community that the public doesn't know that capability even exists."

The big technological problem wasn't pulling the signal out from the cable but separating the channels so someone could understand it.

Running through that one cable was perhaps up to a dozen different lines, all with Soviet voices chattering away.

As Reeds puts it, it was a "gargled cacophony" and nearly impossible to gather any real intelligence.

For this reason, the first mission failed.

"It was trial and error," says Reed, "When they first got the signals in, it was a mess."

But as the mission moved forward, the communication technicians jerry-rigged equipment that separated signals and drew out particular voices.

Exactly what and how they did it remains a mystery as parts of Ivy Bells remains classified.

"These guys were the original makers...

they were making it up as they went along," says Sontag regarding the operation's communication technicians.

"No one else was doing underwater cable tapping. This was all brand new."

President Jimmy Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev sign SALT II treaty, June 18, 1979.

40 Years a Secret

Now retired, David LeJeune was a Navy saturation diver who participated in several later missions.

Although he was unable to answer many questions, he says that the information that he and his fellow divers uncovered led to the successful completion of the SALT II talks, which was eventually signed in 1979 and restricted each country's nuclear delivery systems.

LeJeune also says the tech and gear they were using was cutting edge.

"We were using technology that is so far advanced from the civilian community that the public doesn't know that capability even exists."

For a decade, the U.S. wiretapped this comm line at the bottom of the Sea of Okhotsk.

The Halibut and other subs would venture into the Sea of Okhotsk a couple of times a year, picking up the tap and replacing it with a new and often more advanced one.

It was an intelligence gold mine, consistently providing the U.S. with invaluable information.

"Finding this information turned out to be the thing that let the Cold War end."

"We didn't know...

how much we were frightening (the Soviets)...

until we listened to these tapes," says Sontag, "Very quickly, we pulled back from the brink.

And this had a lot to do with it....

I think finding this information turned out to be the thing that let the Cold War end."

But in 1980, a former NSA employee named Ronald Peltonwalked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington D.C., and for $35,000, divulged the inner workings of Ivy Bells.

With that, the operation abruptly ended—or so it was claimed.

Over three decades later, this type of wiretapping is thought to be largely obsolete.

Thanks to the digital age, there are far more efficient, easier, and less risky ways to spy on someone's comms.

However, these types of underwater cables still exist and are of great importance.

As the New York Times reported in 2015, there are continued fears that these cables could be cut, effectively halting communications across the globe.

But, even though this type of surveillance may be old fashioned, Reed thinks it's possibly still happening today.

"Submarines absolutely still have the capability to do these kind of missions and there are personnel that are still trained on how to do these missions," says Reed.

"Whether or not those missions are still underway, that would be considered classified."

Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum / Darryl L. Baker

Colors lowered for the last time on the USS Halibut, its mission now complete, June 30, 1976.

Colors lowered for the last time on the USS Halibut, its mission now complete, June 30, 1976.

Tuesday, November 25, 2025

Trump administration announces plan for new oil drilling off the coasts of California and Florida

A worker removes oil from the sand at Refugio State Beach, nort of Goleta, California, May 21, 2015

AP photo / Jae C. Hong, file

From AP by Matthew Daly

The Trump administration announced on Thursday new oil drilling off the California and Florida coasts for the first time in decades, advancing a project that critics say could harm coastal communities and ecosystems, as President Donald Trump seeks to expand U.S. oil production.

The oil industry has been seeking access to new offshore areas, including Southern California and off the coast of Florida, as a way to boost U.S. energy security and jobs.

The federal government has not allowed drilling in federal waters in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, which includes offshore Florida and part of offshore Alabama, since 1995, because of concerns about oil spills.

California has some offshore oil rigs, but there has been no new leasing in federal waters since the mid-1980s.

For the first time in 40 years, Trump is working to open California's coast to new oil drilling.

Since taking office for a second time in January, Trump has systematically reversed former President Joe Biden’s focus on slowing climate change to pursue what the Republican calls U.S. “energy dominance” in the global market.

Trump, who recently called climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world,” created a National Energy Dominance Council and directed it to move quickly to drive up already record-high U.S. energy production, particularly fossil fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas.

Trump, who recently called climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world,” created a National Energy Dominance Council and directed it to move quickly to drive up already record-high U.S. energy production, particularly fossil fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas.

Meanwhile, Trump’s administration has blocked renewable energy sources such as offshore wind and canceled billions of dollars in grants that supported hundreds of clean energy projects across the country.

Even before it was released, the offshore drilling plan has been met with strong opposition from California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat who is eyeing a 2028 presidential run and has emerged as a leading Trump critic.

Newsom pronounced the idea “dead on arrival” in a social media post.

The proposal also is likely to draw bipartisan opposition in Florida.

Tourism and access to clean beaches are key parts of the economy in both states.

Plans to allow drilling off California, Alaska and Florida’s coast

The administration’s plan proposes six offshore lease sales off the coast of California.

It also calls for new drilling off the coast of Florida in areas at least 100 miles from that state’s shore.

The area targeted for leasing is adjacent to an area in the Central Gulf of Mexico that already contains thousands of wells and hundreds of drilling platforms.

The five-year plan also would compel more than 20 lease sales off the coast of Alaska, including a newly designated area known as the High Arctic, more than 200 miles offshore in the Arctic Ocean.

All offshore areas “with the potential to generate jobs, new revenue and additional production to advance America’s energy dominance should be considered for inclusion,” the American Petroleum Institute and other groups said in a joint letter to the Trump administration in June.

The groups cited California’s history as an oil-producing state.

“Undiscovered resources could be readily produced given the array of existing infrastructure in the area, particularly in southern California,” the letter said.

Opposition from California and Florida

Sen. Rick Scott, a Florida Republican and Trump ally, helped persuade Trump officials to drop a similar offshore plan in 2018 when he was governor.

Last week, Scott and fellow Florida Republican Sen. Ashley Moody’ co-sponsored a bill to maintain a moratorium on offshore drilling in the state that Trump signed in his first term.

“As Floridians, we know how vital our beautiful beaches and coastal waters are to our state’s economy, environment and way of life,″ Scott said in a statement.

“I will always work to keep Florida’s shores pristine and protect our natural treasures for generations to come.”

A Newsom spokesman said Trump officials had not formally shared the plan, but said “expensive and riskier offshore drilling would put our communities at risk and undermine the economic stability of our coastal economies.”

California has been a leader in restricting offshore oil drilling since the infamous 1969 Santa Barbara spill that helped spark the modern environmental movement.

While there have been no new federal leases offered since the mid-1980s, drilling from existing platforms continues.

Newsom expressed support for greater offshore controls after a 2021 spill off Huntington Beach and has backed a congressional effort to ban new offshore drilling on the West Coast.

A Texas-based company, with support from the Trump administration, is seeking to restart production in waters off Santa Barbara damaged by a 2015 oil spill.

The administration has hailed the plan by Houston-based Sable Offshore Corp. as the kind of project Trump wants to increase U.S. energy production as the federal government removes regulatory barriers.

Trump signed an executive order on the first day of his second term reversing former President Joe Biden’s ban on future offshore oil drilling on the East and West coasts.

A federal court later struck down Biden’s order to withdraw 625 million acres of federal waters from oil development.

Environmental and economic concerns over oil spills

Democratic lawmakers, including California Sens. Alex Padilla and Adam Schiff and Rep. Jared Huffman, the top Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee, warned that opening vast coastlines to new offshore drilling “would devastate coastal economies, jeopardize our national security, ravage coastal ecosystems, and put millions of Americans’ health and safety at risk.’'

Oil spills “not only cause irreparable environmental damage, but also suppress the value of coastal homes, harm tourism economies and weaken coastal infrastructure,’' the lawmakers said in a letter signed by dozens of Democrats.

Oil spills “not only cause irreparable environmental damage, but also suppress the value of coastal homes, harm tourism economies and weaken coastal infrastructure,’' the lawmakers said in a letter signed by dozens of Democrats.

One disastrous oil spill can cost taxpayers billions in lost revenue, cleanup costs and ecosystem restoration, they said.

Joseph Gordon, campaign director for the environmental group Oceana, called the Trump administration’s latest plan “an oil spill nightmare.”

Coastal communities “depend on healthy oceans for economic security and their cherished way of life,’' he said.

“We need to protect our coasts from more offshore drilling, not put them up for sale to the oil and gas industry. There’s too much at stake to risk more horrific oil spills that will haunt our coastlines for generations to come.”

Links :

- WP : Trump officials unveil plan to drill off California, sparking a fight

- Houston Chronicle : Exclusive: Leaked documents detail Trump's plans to open East and West coasts to offshore oil drillin

Monday, November 24, 2025

Will more ships run aground on the Northwest Passage as traffic increases?

MV Thamesborg

From Arctic Today by Christopher Wright

MV Thamesborg is the latest cargo ship to run aground on the Northwest Passage.

Given the lack of charted water in the Canadian Arctic, it’s surprising that more vessels haven’t gotten into difficulties.

On Sept. 6, the Canadian Coast Guard reported that the MV Thamesborg had gone aground in Franklin Strait, a major channel for the Northwest Passage.

The Thamesborg is one of Royal Wagenborg’s four T class cargo ships.

Sailing under the Dutch flag, she was carrying a cargo of carbon anodes for the aluminum smelter at Baie Comeau in the province of Quebec.

The ship stranded at the western tip of the Tasmania Islands, a group of rocky islets on the eastern side of Franklin Strait.

One report said the ship was on a rock pinnacle and that five ballast tanks had been damaged; there was no pollution and no injuries.

The Thamesborg was eventually refloated on Oct. 9, following an unsuccessful attempt to get her off the rocks the previous day.

At the turn of the century, there really wasn’t that much traffic in the NWP.

That began to change in about 2008, and by 2023 there were 13 commercial transits, 11 expedition vessels and the usual flock of yachts and small craft.

The NWP represents only a fraction of actual Canadian Arctic activity, community and mining resupply, as well as mineral shipments make up the bulk of marine movements.

While ships do, very occasionally, find bottom in the Canadian Arctic, what is unusual is the location of this grounding.

We will have to await the conclusions of the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) inquiry for a detailed assessment, and particularly to know why the ship was so far off the usual deep-water track through Franklin Strait.

For example, the Nordic Orion safely transited the strait in 2013 with 73,500 tons coal at 14 meter draft (the maximum depth of an part of the vessel).

Alternative:

This isn’t to say that the Canadian Arctic is without hazards.

A decade ago, the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) reported that only 10% of the Arctic was surveyed to modern standards.

By 2023, around 16% of Arctic waters were adequately surveyed.

The author (on behalf of GNWT and GN) presented a paper at the Canadian Hydrographic Congress (CHC) in 2012 that identified systematic deficiencies in Arctic charting.

Two years later, Canada’s Auditor General issued a damning report on the same issue.

Here is an extract from the 2012 paper:

The CHS catalogue has “946 charts covering all four of Canada’s coastlines plus major inland waterways”.

The current Arctic catalogue (2008) lists 179 charts, or 19% of all charts, however note the distribution of charts in Table 1 below.

(At the time, I was only able to identify 898 charts including small boat and inland waterways.

Major lakes were Lake Athabasca, Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake).

This is how the CHS depicted its Arctic chart catalogue in 2010:

Fig. 1 CHS Representation of areas in the Canadian Arctic that are surveyed to modern standards

Major lakes were Lake Athabasca, Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake).

This is how the CHS depicted its Arctic chart catalogue in 2010:

Fig. 1 CHS Representation of areas in the Canadian Arctic that are surveyed to modern standards

Graphic reproduced with permission of the Canadian Hydrographic Service

There have been other groundings by ships in the NWP, but these are very infrequent and in recent years almost all by expedition passenger ships visiting locations off the recognized transit routes.

An exception was the Hanseatic on Aug.

29, 1996, which was on a normal sailing route when it ran aground.

Here it was found that despite the crew being aware that the usual shoal markers had not been placed that season, the ship depended on a marker that had survived winter ice and was displaced by 200 meters

Another grounding was the Clipper Adventurer in 2010 that stranded on a seamount that had only been discovered in 2007.

The chart revision was subject to a Notice to Shipping (NOTSHIP), but this was not on board the ship.

The route being followed by the ship from Port Epworth to get back onto the NWP track had last been surveyed in 1965 with spot soundings.

Fig. 2 chart extract showing location of grounding

Chart section reproduced with permission of the Canadian Hydrographic Service

The same year the tanker Nanny stranded on a sandbar while exiting Gjoa Haven on Sept. 1.

It was able to get free after lightering some fuel cargo to another tanker.

Although the TSB decided not to investigate after interviewing the crew, the grounding can, in large part, be ascribed to three things: poor charts for the area, the master not being familiar with the waters, and also not having his own notes as to safe approach and anchorage.

Here is a list of known recent groundings in the Canadian Arctic.

Many of these incidents were “touch and go” and didn’t result in damage.

The TSB classifies these incidents as “bottom contact.”

However, there are all sorts of unidentified underwater peaks awaiting the unwary.

For example, even where a consistent survey has been undertaken, line spacings of 1 and 2 kilometers are common and 6 kilometers is not unknown.

Charting has not kept up with traffic growth, and here is how charting of the Arctic compares with Canada’s other coastlines.

This table is also from the 2012 paper to the CHC.

It was based on the author’s estimate of deep draft navigation charts and excluded general (1:1,000,000 or smaller scale charts), small craft and inland lakes charts.

Given the parlous nature of the Canadian Arctic chart catalogue, it is a testament to the inherent caution of Arctic navigators that there have not been more groundings.

Links :

- CBC : Salvaging efforts underway for ship grounded in Northwest Passage

- France24 : As Arctic ice vanishes, maritime traffic boom fuels the climate crisis

- The Conversation : As ice recedes, the Arctic isn’t prepared for more shipping traffic

Sunday, November 23, 2025

How the moon’s gravity creates tides on Earth

How the Moon’s gravity creates tides on Earth.

— Science girl (@sciencegirl) November 20, 2025

pic.twitter.com/y0YTb0z1Py

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)