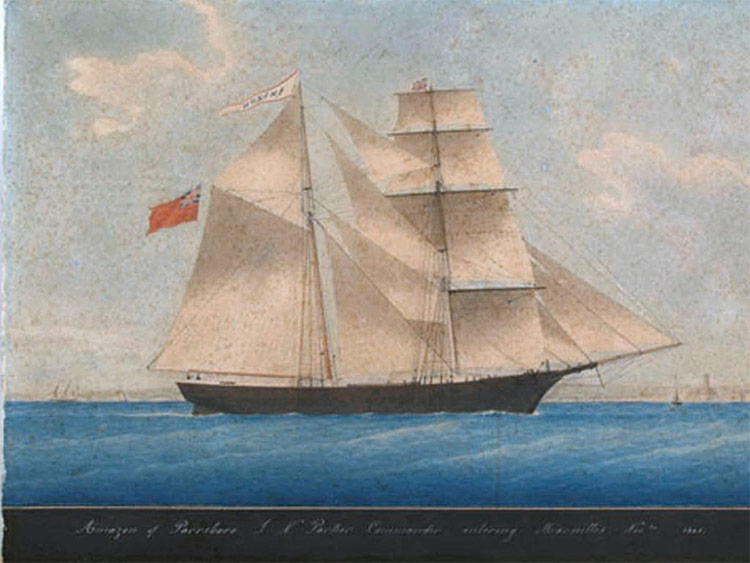

Mary Celeste in 1861, when she was known as Amazon

Mary Celeste in 1861, when she was known as AmazonFrom HistoryToday by Rhys Griffiths

The true story behind the much-mythologised ship and its vanished crew.

In 1884, the ‘phenomenally successful’ literary journal Cornhill

Magazine published, anonymously, J.

Habakuk Jephson’s Statement.

Purporting to ‘subjoin a few extracts’ from an article that appeared in the Gibraltar Gazette, it began:

In the month of December in the year 1873, the British ship Dei Gratia steered into Gibraltar, having in tow the derelict brigantine Marie Celeste, which had been picked up in latitude 38 degrees 40', longitude 17 degrees 15' W.

There were several circumstances in connection with the condition and appearance of this abandoned vessel which excited considerable comment at the time, and aroused a curiosity which has never been satisfied.

The Gibraltar Gazette is fictional, Marie a variation on Mary, and the discovery takes place a year late, but otherwise, the above represents a fairly accurate summary of fact: on December 4th, 1872 a small cargo ship carrying 1700 barrels of alcohol bound for Genoa from New York was found by the Dei Gratia adrift in the Atlantic ocean.

As is now well known, the Mary Celeste was completely abandoned.

Speculation as to what happened to its crew has been a renewable source of debate ever since.

From hereon in, however Jephson’s statement on the fate of the ship and its crew enters the realm of fiction and, arguably, has stayed there ever since.

It was the first work to be published in a major publication by Arthur Conan Doyle, most famous as creator of Sherlock Holmes and victim of the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

Most writers could only dream of creating such an legacy with their first notable work.

Conan Doyle’s sensational solution to the mystery (the culprit is a mutilated stowaway on a cutthroat jihad against all white men) captured public attention to such an extent that the British and American governments were prompted to respond with formal denials and official investigations.

In something approaching a self-fullfilling prophecy, the Statement created an interest in the Mary Celeste that has endured, unsatisfied, for well over 100 years becoming a genre in its own right.

Valerie Martin, author of the Mary Celeste’s most recent fictional outing included Conan Doyle as a character in The Ghost of the Mary Celeste (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2014), but lukewarm reviews of the book suggest that while the reading public is drawn to the mystery, they also like a satisfying conclusion.

Habakuk Jephson’s Statement.

Purporting to ‘subjoin a few extracts’ from an article that appeared in the Gibraltar Gazette, it began:

In the month of December in the year 1873, the British ship Dei Gratia steered into Gibraltar, having in tow the derelict brigantine Marie Celeste, which had been picked up in latitude 38 degrees 40', longitude 17 degrees 15' W.

There were several circumstances in connection with the condition and appearance of this abandoned vessel which excited considerable comment at the time, and aroused a curiosity which has never been satisfied.

The Gibraltar Gazette is fictional, Marie a variation on Mary, and the discovery takes place a year late, but otherwise, the above represents a fairly accurate summary of fact: on December 4th, 1872 a small cargo ship carrying 1700 barrels of alcohol bound for Genoa from New York was found by the Dei Gratia adrift in the Atlantic ocean.

As is now well known, the Mary Celeste was completely abandoned.

Speculation as to what happened to its crew has been a renewable source of debate ever since.

From hereon in, however Jephson’s statement on the fate of the ship and its crew enters the realm of fiction and, arguably, has stayed there ever since.

It was the first work to be published in a major publication by Arthur Conan Doyle, most famous as creator of Sherlock Holmes and victim of the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

Most writers could only dream of creating such an legacy with their first notable work.

Conan Doyle’s sensational solution to the mystery (the culprit is a mutilated stowaway on a cutthroat jihad against all white men) captured public attention to such an extent that the British and American governments were prompted to respond with formal denials and official investigations.

In something approaching a self-fullfilling prophecy, the Statement created an interest in the Mary Celeste that has endured, unsatisfied, for well over 100 years becoming a genre in its own right.

Valerie Martin, author of the Mary Celeste’s most recent fictional outing included Conan Doyle as a character in The Ghost of the Mary Celeste (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2014), but lukewarm reviews of the book suggest that while the reading public is drawn to the mystery, they also like a satisfying conclusion.

Jermoe de Groot, reviewing the book in History Today, described the book as ‘circling around the mystery without seeming to contribute anything purposeful’.

‘I was hoping for a titillating historical-fiction mystery about the real-life vessel Mary Celeste […] What I got was a fragmented and vapid tale about ... well ...

I'm not sure’, complained one reader reviewing the book online.

‘I was hoping for a titillating historical-fiction mystery about the real-life vessel Mary Celeste […] What I got was a fragmented and vapid tale about ... well ...

I'm not sure’, complained one reader reviewing the book online.

Mary Celeste (often misreported as Marie Celeste) was an American merchant brigantine that was found adrift and deserted in the Atlantic Ocean, off the Azores Islands, on December 4, 1872, by the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia.

She was in a disheveled but seaworthy condition, under partial sail, with no one on board, and her lifeboat missing.

The last log entry was dated ten days earlier.

She had left New York City for Genoa on November 7, and on discovery was still amply provisioned.

Her cargo of denatured alcohol was intact, and the captain's and crew's personal belongings were undisturbed.

None of those who had been on board—the captain and his wife, their two-year-old daughter, and the crew of seven—were ever seen or heard from again. Mary Celeste was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia and launched under British registration as Amazon, in 1861.

She transferred to American ownership and registration in 1868, when she acquired her new name, and thereafter sailed uneventfully until her 1872 voyage.

At the salvage hearings in Gibraltar following her recovery, the court's officers considered various possibilities of foul play, including mutiny by Mary Celeste's crew, piracy by the Dei Gratia crew or others, and conspiracy to carry out insurance or salvage fraud.

No convincing evidence was found to support these theories, but unresolved suspicions led to a relatively low salvage award. The inconclusive nature of the hearings helped to foster continued speculation as to the nature of the mystery, and the story has repeatedly been complicated by false detail and fantasy.

Hypotheses that have been advanced include the effects on the crew of alcohol fumes rising from the cargo, submarine earthquakes (seaquakes), waterspouts, attacks by giant squid, and paranormal intervention. After the Gibraltar hearings, Mary Celeste continued in service under new owners.

In 1885, her captain deliberately wrecked her off the coast of Haiti, as part of an attempted insurance fraud.

The story of her 1872 abandonment has been recounted and dramatized many times, in documentaries, novels, plays and films, and the name of the ship has become synonymous with unexplained desertion. In 1884, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story based on the mystery, but spelled the vessel's name as Marie Celeste.

This spelling has now become more common than the original in everyday use. The keel of the future Mary Celeste was laid in late 1860 at the shipyard of Joshua Dewis in the village of Spencer's Island, on the shores of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia.

The ship was constructed of locally felled timber, with two masts, and was rigged as a brigantine; she was carvel-built, with the hull planking flush rather than overlapping.

She was launched on May 18, 1861, given the name Amazon, and registered at nearby Parrsboro on June 10, 1861.

Her registration documents described her as 99.3 feet (30.3 m) in length, 25.5 feet (7.8 m) broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet (3.6 m), and of 198.42 gross tonnage.

She was owned by a local consortium of nine people, headed by Dewis; among the co-owners was Robert McLellan, the ship's first captain. For her maiden voyage in June 1861, Amazon sailed to Five Islands to take on a cargo of timber for passage across the Atlantic to London.

After supervising the ship's loading, Captain McLellan fell ill; his condition worsened, and Amazon returned to Spencer's Island where McLellan died on June 19.

John Nutting Parker took over as captain, and resumed the voyage to London, in the course of which Amazon encountered further misadventures.

She collided with fishing equipment in the narrows off Eastport, Maine, and after leaving London ran into and sank a brig in the English Channel.

She was in a disheveled but seaworthy condition, under partial sail, with no one on board, and her lifeboat missing.

The last log entry was dated ten days earlier.

She had left New York City for Genoa on November 7, and on discovery was still amply provisioned.

Her cargo of denatured alcohol was intact, and the captain's and crew's personal belongings were undisturbed.

None of those who had been on board—the captain and his wife, their two-year-old daughter, and the crew of seven—were ever seen or heard from again. Mary Celeste was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia and launched under British registration as Amazon, in 1861.

She transferred to American ownership and registration in 1868, when she acquired her new name, and thereafter sailed uneventfully until her 1872 voyage.

At the salvage hearings in Gibraltar following her recovery, the court's officers considered various possibilities of foul play, including mutiny by Mary Celeste's crew, piracy by the Dei Gratia crew or others, and conspiracy to carry out insurance or salvage fraud.

No convincing evidence was found to support these theories, but unresolved suspicions led to a relatively low salvage award. The inconclusive nature of the hearings helped to foster continued speculation as to the nature of the mystery, and the story has repeatedly been complicated by false detail and fantasy.

Hypotheses that have been advanced include the effects on the crew of alcohol fumes rising from the cargo, submarine earthquakes (seaquakes), waterspouts, attacks by giant squid, and paranormal intervention. After the Gibraltar hearings, Mary Celeste continued in service under new owners.

In 1885, her captain deliberately wrecked her off the coast of Haiti, as part of an attempted insurance fraud.

The story of her 1872 abandonment has been recounted and dramatized many times, in documentaries, novels, plays and films, and the name of the ship has become synonymous with unexplained desertion. In 1884, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story based on the mystery, but spelled the vessel's name as Marie Celeste.

This spelling has now become more common than the original in everyday use. The keel of the future Mary Celeste was laid in late 1860 at the shipyard of Joshua Dewis in the village of Spencer's Island, on the shores of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia.

The ship was constructed of locally felled timber, with two masts, and was rigged as a brigantine; she was carvel-built, with the hull planking flush rather than overlapping.

She was launched on May 18, 1861, given the name Amazon, and registered at nearby Parrsboro on June 10, 1861.

Her registration documents described her as 99.3 feet (30.3 m) in length, 25.5 feet (7.8 m) broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet (3.6 m), and of 198.42 gross tonnage.

She was owned by a local consortium of nine people, headed by Dewis; among the co-owners was Robert McLellan, the ship's first captain. For her maiden voyage in June 1861, Amazon sailed to Five Islands to take on a cargo of timber for passage across the Atlantic to London.

After supervising the ship's loading, Captain McLellan fell ill; his condition worsened, and Amazon returned to Spencer's Island where McLellan died on June 19.

John Nutting Parker took over as captain, and resumed the voyage to London, in the course of which Amazon encountered further misadventures.

She collided with fishing equipment in the narrows off Eastport, Maine, and after leaving London ran into and sank a brig in the English Channel.

There are some great pieces of mystery fiction set aboard ships.

The ‘framing’ device used by Conan Doyle might put readers in mind of later works like Stefan Zweig’s novellas Chess and Amok, or Bram Stoker’s Dracula where the count arrives at Whitby aboard a ghost ship in a case of reverse colonisation that would send titillating shudders through Victorian England.All the above titles were read voraciously by the reading public, arguably satisfying a hunger fanned by Conan Doyle with his popularisation of the Celeste story years before.

Worth noting, however, is that the impact of Conan Doyle’s story belies the fact that he lived in an age where the day’s biggest authors – HG Wells, Zweig, Robert Louis Stevenson – enjoyed the sort of mass readership that enabled them to shape public belief.

The Celeste myth was a product of a time when literary fiction was at its most powerful: it’s a matter of debate as to whether Conan Doyle’s modern day contemporaries could exert the same influence.

Worth noting, however, is that the impact of Conan Doyle’s story belies the fact that he lived in an age where the day’s biggest authors – HG Wells, Zweig, Robert Louis Stevenson – enjoyed the sort of mass readership that enabled them to shape public belief.

The Celeste myth was a product of a time when literary fiction was at its most powerful: it’s a matter of debate as to whether Conan Doyle’s modern day contemporaries could exert the same influence.

Links :

- Smithsonian Mag : Abandoned Ship: The Mary Celeste

- CBC : A N.S. ghost ship is fading from memory — 150 years after its crew disappeared

- AccuWeather : Could weather hold the secret to history's greatest ghost ship mystery?

- The Mary Celeste website

- The Telegraph : On this day in 1872: the Mary Celeste was found adrift in the Atlantic, inexplicably deserted

- The Guardian : The Ghost of the Mary Celeste by Valerie Martin – review

- NYT : The Ghost of the Mary Celeste by Valerie Martin – review

- WP : ‘The Ghost of the Mary Celeste,’ by Valerie Martin

No comments:

Post a Comment