Saturday, January 4, 2025

Jules Verne trophee : Sodebo Ultim in the Indian Ocean

Friday, January 3, 2025

Arcona yacht sinking: couple share how they tried to save their boat after the rudder stock broke

“I was down below and I didn’t hear the sound. People have asked us

if we hit something but I heard no sound at all inside the boat. Ingmar

heard a short, sharp sound underneath where he was standing. He called

me and said “Look at this, I have no rudder” and he could turn the wheel

with a finger.

My first thought was the chain had snapped so I opened up the hatch and

the rudder stock was broken immediately below the steering quadrant

inside the lazarette. That was not what I expected to see,” explained

Katarina.

According to the Arcona website, the Arcona 460 rudder is made of glass fibre with multiaxial roving, and filled with polyurethane foam.

Initially, they tried to use an inflatable repair kit to plug the hole, but the part in the valve to blow it up was missing. Instead, they used a diver’s surface marker buoy, but sharp plastic punctured it.

However, the water pressure caused the disc to leak when the stern pumped in the waves,” said Ingmar.

Thursday, January 2, 2025

Year in review: the impact of geopolitical conflicts on maritime trade in 2024

The year 2024 is likely to be remembered for significant geopolitical conflict and rising tensions between several nations.

Recent disruptions in global maritime trade have significantly affected key routes such as the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

Seafarers on the front lines

The escalating geopolitical tensions and maritime conflicts of 2024 have placed seafarers at significant risk, transforming critical waterways into active danger zones.

These threats not only endanger lives but also create immense psychological stress for crew members, who must navigate volatile waters while fearing for their safety.

Beyond physical harm, seafarers have also faced prolonged detentions, such as the crew of the MV Galaxy Leader, and the constant anxiety of operating in regions prone to hostilities.

To put the numbers into perspective, the Philippines’ Department of Migrant Workers (DMW) reported that 740 Filipino seafarers had been victims of attacks while navigating the volatile waters of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden up to November 2024.

As these dangers persist, protecting seafarers and ensuring their welfare must become a global priority. Stronger security measures, enhanced mental health support, and robust diplomatic efforts are essential to mitigate risks in high-conflict zones.

The geopolitical instability in the Middle East has been significantly heightened since October 7, 2023, when Hamas launched a terrorist attack in Israel, setting off a chain of regional conflicts.

Since November 2023, the Houthis have aligned with Hamas, targeting vessels in the Red Sea with ballistic missiles and explosives, resulting in approximately 90 reported attacks.

In response, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2722 in January 2024, condemning these attacks and calling for an immediate cessation.

Beyond the security threat, the conflict has also presented significant environmental risks.

Furthermore, the ongoing hostilities in the Red Sea have led to increased carbon emissions from ocean freight shipping, as vessels are forced to avoid the region and reroute through the Cape of Good Hope. According to the Xeneta and Marine Benchmark Carbon Emissions Index (CEI), emissions reached a record high of 107.4 points in Q1 2024, driven by a 63% rise in emissions for shipments from the Far East to the Mediterranean, and a 23% increase for shipments to Northern Europe.

In addition to the Red Sea, the Black Sea has also seen considerable disruption due to missile attacks on Ukraine’s southern port infrastructure.

Furthermore, 2024 witnessed a significant rise in shadow fleet activity, driven largely by sanctions imposed by the EU and other nations.

According to Gibson, nearly 63% of tankers built in 2009 or earlier are now engaged in grey fleet activity, often trading sanctioned goods from countries like Iran, Venezuela, and Russia.

Additionally, shadow fleet activity has expanded to LNG vessels.

The economic impact on global supply chains

According to UNCTAD’s Review of Maritime Transport 2024, freight rates surged in 2024 due to rerouted vessels, port congestion, and rising operational costs.

The impact is especially severe for vulnerable economies that rely heavily on maritime transport.

Furthermore, Lloyd’s of London highlighted that with more than 80% of the world’s imports and exports – around 11 billion tons of goods – at sea at any given time, the closure of major trade routes due to a geopolitical conflict is one of the greatest threats to the resources needed for a resilient economy.

Looking Forward

From the escalating threats in the Middle East to the rise of shadow fleet activity, the maritime industry is confronting a series of unprecedented challenges.

Wednesday, January 1, 2025

Reading the seas: our top ocean books of 2024

Dialogue Earth’s team have been reading up on ancient monsters, rising waters, murky depths and more – here are a few of their choice picks

Wild seas, high seas, mapping the bottom and determining where the top really is – ocean-focused books published this year cover an incredible range, both literally and metaphorically.

Here are some of our favourite ocean reads from 2024.

What the Wild Sea Can Be – Helen Scales

A sea change has unfolded beneath the vast surface of the ocean over the last few hundred million years.

In her latest book, marine biologist Helen Scales rewinds the clock to sketch out this shift, starting with the trilobites that swam, crawled and drifted in ancient seas.

Swimming reptiles – including sea-monster-like ichthyosaurs – claimed marine dominance until the Permian extinction, which also led to the overthrow of the dinosaurs, hit some 250 million years ago.

Scales dusts off this tumultuous, pre-human past to offer a sobering lesson about the current state of our ocean, and its potential future.

A mass extinction is currently underway.

“Whichever way you slice the data, the rate of extinction is now far higher” than the normal rate shown in the fossil record, she writes.

In today’s climate and biodiversity crisis, some species will win, and others will lose.

The rapidly spreading, adaptive lionfish remains strong in the changing ocean, boldly cruising in non-native waters.

On the other hand, emperor penguins frown at Antarctica’s disappearing sea ice, which is critical to raising their offspring.

Responding to the unfolding calamity, humans, again, endeavour to “invent their way out of trouble”, Scales notes.

They advance innovative plans such as floating cities and mining the deep sea.

But Scales prefers to let the ocean do its thing – to regenerate and recover on its own.

To allow that, humanity has to restrain itself and occasionally offer it a helping hand.

This includes by reintroducing species, curbing industrial fisheries and no longer treating the ocean as a forgiving dumping ground for plastics and sewage, she suggests.

Zestful and imaginative, the book shines a much-needed light on the hope for our ocean, alerting us that the wheel steering its course is in our hands.

– Regina Lam

The High Seas – Olive Heffernan

Like many who write about the ocean, Olive Heffernan starts by describing a childhood within reach of the sea.

But her journey has taken her far offshore: this book explores the “unclaimed ocean” that lies beyond the control of individual nations.

Heffernan, a journalist who founded the Nature Climate Change journal and has contributed to Dialogue Earth among other outlets, first headed to the high seas in 2001.

In this deeply readable book, she takes us on a voyage with a motley collection of people, ships and creatures in a place that, as she says, most people will only see from aeroplane windows.

Her book details how this zone is not the lawless space of popular imagination, but a realm overseen by a “mish-mash of organisations and bodies”, many of which “wilfully ignore science and disregard expert advice”.

This has left much of the high seas under-protected in a time of widespread overfishing, seabed mining attempts and huge ecosystem changes brought on by climate change.

Heffernan’s book arrives at an apposite time – the year before it was published, governments agreed a treaty on conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction, called the BBNJ or High Seas Treaty.

Although it needs to be ratified by many more countries before it comes into force, Heffernan calls the deal “a major win for conservation”.

But she notes that while she hoped to produce an uplifting vision of the future to end her book, pessimism set in.

In the end, she returns to the shoreline with a plea to not see the high seas as an “other”, but as a place connected to more familiar territories closer to home, and to us.

– Daniel Cressey

Mapping the Deep – Dawn Wright

This inspiring read follows the first Black person to go to the deepest place on Earth, the Challenger Deep trench in the western Pacific Ocean.

Its hero is the oceanographer Dawn Wright, chief scientist at geographic information company Esri (formerly the Environmental Systems Research Institute).

She made the voyage in 2022 with her compatriot, financier-turned-explorer Victor Vescovo.

The book charts Wright’s personal journey from a childhood spent living next to the beach in Maui, to a career mapping the ocean floor.

Like a winding conversation with a group of people who love the subject of deep-sea exploration, it then widens out to touch upon oceanography’s women trailblazers, the current deep-sea mining debate, the history of humans in submersibles, Earth’s deepest shipwrecks and lots more.

In recent years – particularly since the Black Lives Matter movement wrestled its way into mainstream consciousness in 2020 – the climate action movement has been at pains to map out its symbiosis with ongoing struggles for equality around the world.

But that is not an easy relationship to distil into a catchy placard or a pithy media soundbite.

Mapping the Deep takes the time to present Wright’s very specific example and carefully lay it all out for the reader.

It also contains insightful quotes from many others, including the first person to complete both a spacewalk and a trip to Challenger Deep, Kathy Sullivan (the “most vertical person in the world”), and the film director and ocean enthusiast, James Cameron.

This cast of extras reflects Wright’s repeated assertion that having a supportive community of family, friends and colleagues enabled her achievements.

Written lucidly and accompanied by an engaging collection of photographs, diagrams, explanatory asides and illuminating personal anecdotes, Mapping the Deep is perfect for anybody with a thirst for exploration – especially young adults looking for inspiring role models.

– Neil Simpson

Sea Level – Wilko Graf von Hardenberg

The ocean is rising, and faster now than ever before.

The rate of “global mean sea level” rise is up from 1.4mm per year for most of the 1900s to over 3mm annually since the turn of the millennium, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

By the end of the century, the level could be over half a metre higher than at the end of the 1900s, even if the greenhouse gas emissions that are melting glaciers and sea ice, and expanding the ocean by making it warmer, are largely curtailed.

But what do such measurements actually mean, when the difference between high and low tide can reach over 10 metres in some extreme locations?

Historian Wilko Graf von Hardenberg examines how “sea level” is a baseline that’s often taken as a certainty when it is actually “far from a natural index – a product of technically and culturally determined assumptions”.

From examining how it was produced, he goes on to chart how sea level was then re-imagined as an exemplar of change brought about by anthropogenic warming.

The “global mean sea level” familiar from climate change warnings turns out to actually be just one possible way of looking at the height of the ocean – just as the Greenwich meridian is only one possible baseline for longitude.

Von Hardenberg notes that between his first thoughts on this book in 2011 and its completion in 2022, global sea levels rose by 5cm.

They are not done rising yet, and this book offers a fine explanation of why these apparently small and certain measurements are worth thinking more carefully about.

– Daniel Cressey

Tracks on the Ocean – Sara Caputo

Lines on maps have real power to influence the world, defining claims of ownership and entitlement.

In Tracks on the Ocean, maritime historian Sara Caputo looks at the inky threads made on sea charts to showcase examples of navigational prowess, or sometimes, how they inadvertently record a lack thereof.

Caputo reveals that, while there has been a long history of outlining routes, tracing individual journeys via such lines appears to have only started in the 16th century.

The revolutionary idea that a journey is noteworthy enough to leave a permanent mark, too, has a “fundamentally watery” origin, she notes.

(Image: Profile Books)

“It is also inextricable from the development of European sea-bound empires,” she writes, as she retraces the traces of voyages; some famous, some fictional, some largely forgotten.

These lines are for gathering knowledge, but also for making claims: “a storytelling tool”, she observes.

Caputo’s approach is scholarly and occasionally more academic than a beach read, with philosophy and historiography on full display.

But through this, she makes the creation of ocean tracks come to life.

Crucially, Caputo acknowledges that most of the tracks she applies her gaze to represent the workings of powerful, white men acting out colonialism and environmental conquests.

This raises the question of who has not left such traces, or not been allowed to leave them.

Caputo’s book notes some of their stories: the lowly sailors on epic voyages, who did the hard work.

Women like Mina Benson Hubbard, who journeyed into Labrador by canoe, accompanied by four (unnamed) Indigenous men, and had her exploration characterised in media reports at the time as a sentimental jaunt.

And, of course, all those Indigenous people who made vast ocean journeys long before captains of famous European ships, but perhaps preferred to record them in chants rather than on charts.

As humanity seeks increasingly to delineate the oceans, both for exploitation and for protection, it is well worth considering the origins of how lines on maps are made, and why.

– Daniel Cressey

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

How 4 guys over 50 are training to row across the Atlantic

Three years ago, four friends committed to a lofty goal: row a boat 3,000 miles from the Canary Islands just off the coast of Africa, all the way across the Atlantic Ocean to Antigua.

The UK-based team are all water sport and adventure enthusiasts, each with his own niche.

Dan Dicker (52) is the group's techie, Jon Wilburn (52) is the ocean navigation specialist, Jason Howard (59) is the medical and physical support, and Steve Potter (62) is the "oldie with muscles of steel and unflappable constitution."

The men will be at sea for what could be over 50 days.

They'll spend those 50 days alternating two hours of rowing, two hours of rest, day and night.

While they're excited for their grueling endeavor, their goals for the undertaking extend beyond that.

There's the change they've worked to inspire in their communities.

The awareness and support they've worked to raise for causes they care deeply about.

Diabetes awareness, cancer research, and efforts to curb ocean pollution are all top of mind.

The team embarks on their journey on December 12th.

In early November, Men's Health got a chance to sit down with teammates Jason and Steve to discuss how they're preparing for the journey physically, emotionally, and mentally.

MEN'S HEALTH: How did the idea of participating in the World's Toughest Row come about?

STEVE POTTER: John and I have been thinking about it for about 20 years, and then about three years ago, he said, "if we're going to do it, we need to do it now." And Jason and I completed a course out in the Mediterranean about three years ago, and Jason was very keen on getting on board.

And then John rang up a friend from university, Dan, and he immediately said yes.

We've been campaigning since.

JASON HOWARD: It's amazing how much goes into all the preparation.

There's so much that goes into it, in terms of sponsorship, preparing everything, getting the boat, getting all our kits ready, and doing all the competencies that we have to do.

It's a tremendous amount of work, and it's taken us three years to pack all that in.

SP: One thing we decided quite early on was we wanted this to have bigger impact.

There are three elements to it.

There's the the selfish element of, yeah, we want to row across the Atlantic, but we also want to use the opportunity to reach out to youngsters in our community.

We've been to about 45 to 50 schools in our area, and we talked to them about the benefits of getting out of your comfort zone and getting out there and going for a walk on the beach or playing in the woods—getting away from all these devices.

It's about making sure you get outside, appreciate the big outdoors, and personally speaking, I've really enjoyed that element of it.

The third bit is we want to raise money for our three charities: diabetes, cancer research and a little local one called the Final Straw, which looks at reducing plastic waste out at sea.

MH: What all does your physical training entail?

JH: We've had quite a number of weekends on the water.

We all live in slightly different areas of the UK.

And we'd meet at our our boat, which is now on its way over to the Canary Islands in a shipment container.

We've had our boat on the south coast, so we all meet there, train all weekend, and go back to work the next week.

So we sort of fit many weekends in like that, which has been great to be able to get on the water.

We've done that for about 18 months now.

We each have a specific training program which has been building up, really, since January this year.

They're designed for flexibility, strength, and endurance.

Some of it is pretty tough.

When you have to fit in a two and a half hour row as well as a day's work, it's quite a lot to fit in.

That's part of the challenge in testing our bodies.

It's been great to be able to push ourselves and to know that anything is still possible.

We've been fortunate enough to have had our boat for 18 months to train on it.

There's some very tiny little cabins at either end, and all navigation and electronics [equipment] is in one of those cabins.

When the weather's really, really bad, we put out something called a power anchor, which is basically like a big parachute to stabilize the boat.

And we literally just have to get in our cabins, close the doors, and ride it out.

We expect to hit those sort of storms at certain times.

We've all had to do competencies in navigation, sea survival, that sort of stuff.

MH: Has your diet changed at all?

JH: We've been wearing Lingo [continuous glucose monitor] biosensors since January, so 11 months.

They're one of our sponsors.

Part of that is to help steer us and guide us with our performance and nutrition.

It's helped in terms of timing what to eat and when, to support our training.

We're going to be wearing the sensors for the duration of the event, too, and it'll be really interesting to see the data that comes back from that.

We'll need to eat about 5,500 calories a day, and we're going to certainly be eating a lot more in the way of carbohydrates than we are now.

If we're doing two hours [rowing] two hours [rest] for those 50 days, it's going to be an interesting thing to have a look at the pattern that develops.

Obviously, our food while we're away is very different.

It's all expedition rations, you know.

We've got a jet boiler, which boils us up some hot water on the boat, which we add to the rations.

And that's it, really.

MH: What are you doing to prepare mentally?

SP: We've all talked about things that we're most worried about, risk, etc.

But we are also working with a university sport science department, so we've got four sessions coming up with a sports psychologist, which will help.

JH: We've decided that we want to enjoy this event.

We also realize we're going to hit some dark spots, and that's part of it.

It's 50 days where we don't see anything but sea and we're going to have our highs and lows.

If we hit a storm, if we hit 60 foot waves—which we will—we [might] get thrown out of the boat repeatedly.

And I'm sure we're going to deal with fatigue and sleep deprivation, and we're gonna find it very hard mentally.

Even the smallest things will start to annoy us.

But we're all good friends, and we know each other well.

We're all sensible, and we don't panic too much.

I think we're all fairly level headed.

We've planned to have a 10 to 15 minute break every day to actually sit down and just chat amongst ourselves about what our concerns are, what's pissing us off.

We have to clear the air, no matter how big or small it is.

Part of the the learning and part of the event is actually supporting each other.

We've got to be able to perform.

We've got to keep the boat moving.

And we're not the oldest crew, potentially.

But, I think our combined ages are certainly over 220 years.

So we're getting on a bit.

There are some young guns out there, and we hope to be able to put a good performance in.

SH: I think mentally, Jason, we're going to be far better prepared than the youngsters.

JH: [Laughs]

MH: What are you most nervous for? Most excited for?

JH: One of the things is the weather.

I think the daunting thing is, when you first get hit by a big storm, figuring out what it's going to feel like.

We know the boat can survive.

Our boat has done three trips already.

It's a good, robust boat in the big waves.

I think that'll be exciting once we get used to it.

But the big waves will be quite terrifying, I'm sure, to start with.

From a fitness perspective, I think we're ready.

I think we'll cope, you know.

Our bodies will cope.

I think we're most excited to start, really.

I think we're all ready.

The [island] where we set sail from is the hub of the World's Toughest Row.

It's a really exciting place.

There's a good vibe.

It's a nice atmosphere.

All the crews really sort of gel together so that'll be fun.

That's something we look forward to.

And of course, all of us have been quite careful with our diet and our training, so I think that first beer when we get to Antigua will certainly be high on the agenda.

The message for us is the thing.

All the sponsorship has been a big thing for us to be able to get everything together, all the equipment costs, everything that's that's needed for the event.

Now for us, it's basically creating much as much awareness as we possibly can for our charities.

Diabetes is a personal one for me, because my son's Type 1 diabetic, and he's really been helped with sensor technology.

And, obviously that's not available to everybody.

We've all been touched by friends and family with cancer.

We want to see a legacy with our event.

Monday, December 30, 2024

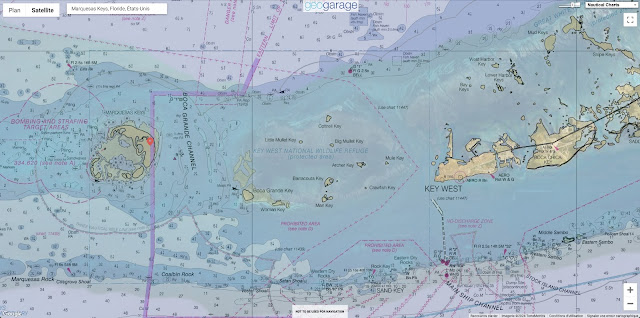

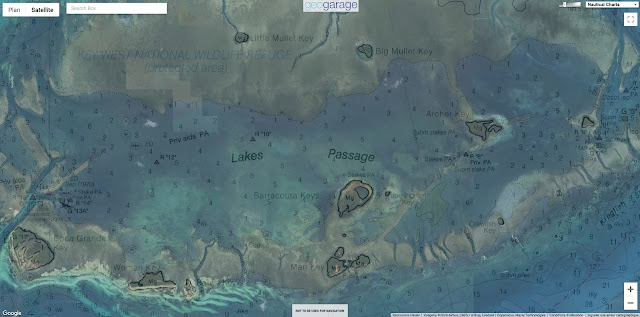

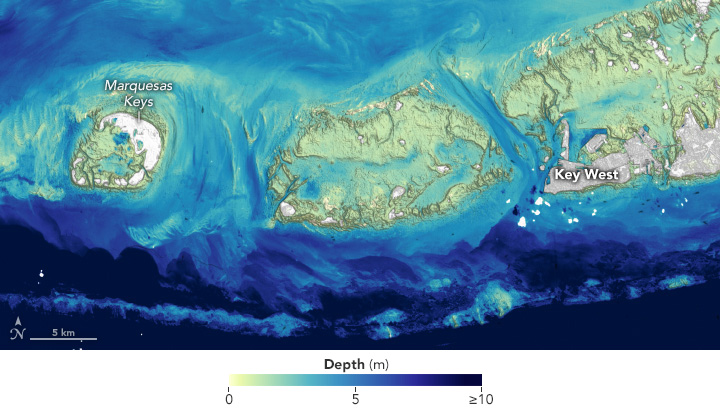

Landsat plumbs the (shallow) depths

As the workhorses for Earth science from space, Landsat satellites have imaged Earth’s land surfaces uninterrupted for over 50 years.

Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey have developed a new way to measure ocean depth, or bathymetry, in shallow nearshore environments using Landsat data.

The new method, described in a 2024 paper in the journal Remote Sensing, relies upon visible-light observations by the OLI (Operational Land Imager) and OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) sensors on the Landsat 8 and 9 satellites, coupled with a heavy dose of physics calculations.

The calculation is relatively straightforward in clear water with a bright bottom.

This algorithm was applied to several coastal areas containing coral reefs, including the Florida Keys, shown here.

In clear water, it is possible to map depths greater than 20 meters (65 feet), much deeper than expected, said Minsu Kim, the remote sensing and ocean optics expert who led the method’s development. Crucially, the method works without external calibration, although it can be refined by incorporating bathymetry measurements from other sources.

Coral reef zones were good candidates for piloting this method because they influence sediment transport, affect coastal erosion, and provide critical habitat to much of the world’s marine life, said physical geographer Jeff Danielson, co-author of the paper and leader of the USGS Coastal National Elevation Database (CoNED) Applications Project.

Despite the need for refined shallow-water maps, however, producing them has remained a practical and technical challenge.

The quest to outsource this onus to satellites includes a pioneering effort by oceanographer Jacques Cousteau.

The cross-purposing of remote sensing instruments for bathymetry has continued from there. Subsequent techniques have included using turbidity as imaged by Landsat as a proxy for depth; combining altimetry measurements from NASA’s ICESat-2 (Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2) with ship-based sonar; deriving depth from stereo imagery; and applying an algorithm to digital photography from the International Space Station.

With the new satellite-based method in hand, Kim, Danielson, and colleagues are looking to scale up nearshore measurements.

In the United States alone, coastal waters are currently only 52 percent mapped, Danielson noted. Initiatives such as the National Ocean Mapping, Exploration, and Characterization (NOMEC) and the global Seabed 2030 project are working to increase mapping coverage, alongside the USGS’s CoNED pursuit to assimilate data that now includes Landsat-derived water depth.

Sunday, December 29, 2024

Trawler towed by SNSM lifeboat

Trawler towed by SNSM lifeboat.

Volunteers from the Calais and Dunkirk stations assisted the French trawler in heavy seas. SNSM Calais

Winds gusted to over 100 km/h, causing waves of up to four meters.

The Centre régional opérationnel de surveillance et de sauvetage (CROSS) Gris-Nez immediately engaged the intervention, assistance and salvage tug (RIAS) Abeille Normandie to carry out the tow, as well as the SNS 077 Notre Dame du Risban from the Calais station (Pas-de-Calais) to secure the operation.

Arriving on site, the Abeille Normandie managed to pass a trailer to tow the trawler. However, it soon gave way under the force of the elements.

The three vessels arrived at the entrance to the Dunkirk harbor channel during the night.