Legendary ocean researcher Sylvia Earle shares astonishing images of the ocean -- and shocking stats about its rapid decline -- as she makes her TED Prize wish: that we will join her in protecting the vital blue heart of the planet.

Saturday, August 2, 2014

Mission Blue - Official trailer

Legendary ocean researcher Sylvia Earle shares astonishing images of the ocean -- and shocking stats about its rapid decline -- as she makes her TED Prize wish: that we will join her in protecting the vital blue heart of the planet.

Friday, August 1, 2014

What I learned from sailing across the Atlantic

For more details and more adventures, check it out!

From Buffer by Rodolphe Dutel

Last year I decided to sail across the Atlantic.

I previously had spent 3 months learning how to sail in South Africa and figured that learning should be put to good use–otherwise there’s no point, is there?

After some quick research, I decided to join the 270 boats crossing the Atlantic with the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) in November 2013:

“Every November since 1986 the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) has set sail from Las Palmas, bound 2,700 nautical miles westward across the Atlantic to the Caribbean.”

Nearly a year later, I can say this trip exceeded my expectations by far.

It taught me a lot about resilience, dedication, practical thinking and creativity.

Sailing is exhilarating.

Sailing with great and passionate people is paradise.

Here’s a recap of my experience and what I learned.

How to find a boat: Persistence pays off

Finding a boat was a tricky part.

Competition is fierce: There’s at least a 3:1 ratio between folks looking for a crossing and yachts offerings spots.

Most skippers start gathering crews up to one year prior to departure.

So, what’s the best way to convince people that you are the best possible crew to cross the Atlantic when you don’t know anyone?

Let’s email people! Exactly one month prior to ARC’s start, I started contacting people.

Of 27 emails sent, I got 19 replies: a 70% ratio is quite nice.

17 didn’t have any spot but agreed to keep an eye out, another 2 boats agreed to meet me for an interview in Gran Canaria.

I booked a one-way ticket to Grand Canaria, packed my stuff and printed business cards.

If all else failed, they would come in handy when I walk the docks.

After two interviews, I got accepted onboard Dory.

She’s a Bavaria 47 skipped by Jon and Trude, a very nice couple from Norway.

They welcomed me on their boat and made us feel like a big family.

We would be a total of 4 people on the water for about 3 weeks.

What to pack ?

Crossing involved going through cold temperatures in the middle of the Atlantic at night to extremely warm in the Caribbean. Humidity was the only constant here.

What to bring: I made a list of everything I took with me.

I immediately lost a few items, the usual. Dory had a water maker (making sea water drinkable!), 3 solar panels, 1 wind mill, 1 electrical generator (gasoline) and about 300L of diesel in total, that was enough to make us energy sufficient for a month or more (electricity, water and fuel). We left shore with great quantities of fruits, vegetables, and deep-frozen vacuum-packed meat (chicken/beef/pork/bacon).

Usual snacks include peanuts, chocolate and fruits (limited supply!). Pictured here is about half of our food (and Trude looking delighted), including large amounts of Nutella.

Setting sail

It’s a strange feeling to go out knowing that you won’t be back on land for about a month.

(My longest previous sailing trip was 4 or 5 days away at sea in South Africa.)

It feels just like going out sailing for a day, but with a more adventurous taste to it.

We left Gran Canaria on Nov. 24, with an estimated arrival time of Dec. 15, give or take 5 days.

Our departure day was incredible.

About 10 friends and family members came around to the marina to wish us farewell on our journey.

The ARC s a big deal for the city of Las Palmas in Gran Canaria.

It’s the world’s largest transatlantic cruising rally; about 200 boats leave the island on the same day.

They treated us very well: fireworks the night before launch, a marching band and hundreds of locals and tourists watching us cast off on that Sunday afternoon.

Living on board: Finding a new rhythm

Our first day was filled with excitement.

Our second and third days required some adjustments, we all felt the transition from the usual rhythm to the cruising life, slight dizziness and and feeling tired.

All your daily activities (especially eating & sleeping) are heavily affected by the weather.

Small details like humidity have big impact on how you live aboard.

When my cabin’s hatch was leaking, it took me about 3 days to find a weather window to empty my cabin and dry it all, including clothing, papers, electronics and bank notes.

Another time, while lying down in my cabin, the boat took a strange turn and I ended up upside down: As I stretched my legs, they found the roof/ceiling.

Every day, we take a daily turn for cooking and galley cleaning.

I got to serve my almost famous “Cape Town curry” more than once, and Trude and Jon baked fresh bread every week!

Cooking was quite a performance: Dory was often hit by waves, and heeling over quite a bit.

I have no memory of cooking without holding on to something.

Some days, it was almost impossible to cook: Knives flew, boiling water was spilled and tomato sauce had an ongoing affair with the white couch.

Challenging conditions and general state of exhaustion made us truly appreciate each and every meal, we all worked hard to have a happy and well-fed crew.

We all very much looked forward to dinner every night.

On a 16-meter long boat, it’s priceless to have your own space.

Luckily, onboard Dory I had my own cabin and own bathroom: fantastic!

One day, in the middle of the Atlantic, we met a German boat that came close enough from Dory to say hi.

They had a crew of… 10 people!

Even on a slightly larger boat, that’s a lot!

Working on board: A 24/7 routine

As a group of four, we worked in pairs on “watches”: In fair weather, we were on watch for 4 hours, then 4 hours off. In rough weather, we either had rolling watches (three people on deck with two hours on, one hour off) or shorter watches (3 hours on, 3 hours off).

Obviously, all those routines apply 24/7.

Here’s a typical schedule” on from 8pm-midnight, off til 4am, back at it from 4-8am, nap until lunch and get back at it after 12, and so on and so forth.

When you are on watch, you trim the sails, operate the radar if needs be, fix minor things and talk to the stars (optional).

Dory was a well-equiped boat with two autopilots: an electrical one, and a Hydrovane (a beautiful wind-based auto-steering mechanism), both were extremely useful.

We sometime got smooth, sunny sailing, yet there was no norm.

Weather changes fast, and local anomalies happen.

Another world

Spending about a month with no email/phone communication was quite refreshing

(our trip was GPS tracked through Google Maps Yellow brick for friends and family).

- I saw 0 ads/commercials (others than branded items on the boat)

- My phone was in airplane mode at all times (only used as a MP3 player)

- I watched less than 2 movies (although we had 100s on board and many devices)

- I wrote more than I had in years, I read 14 books

Would I enjoy living my life this way on the long run?

I don’t think so, but it was well worth trying.

Our sleeping and eating patterns revolved around what the weather was doing.

We kept all our watches on UTC time for the entire trip, it was quite odd readjusting the time once we got to Saint Lucia (4 hours time difference).

On shore, I usually get 8-9 hours sleep a night, onboard it takes some time to practice resting by 1, 2 or 4 hours break.

After some time, just like in most situations: If you are tired enough, sleep will find you.

A little bit of magic

Sailing helps you discover a new kind of magic.

Not all of it can be written down, I’ll try my best to explain it:

We sat in the cockpit at all possible hours of the day, it was fantastic.

You get to see the stars, the Milky Way, the moon and dozens of shooting stars for hours.

Below your feet, many thousands of meters of depth with strange and unknown creatures.

Nothing around you, yet your tiny yacht is making way on a huge ocean.

It’s a unique and privilege feeling to simultaneously have a huge and tiny space for yourself.

We spotted dolphin pods, swimming around Dory’s bow at dusk, being their playful selves.

We saw wild birds, hundred of miles offshore, and wondered how they got there.

At night, Dory would often have fluorescent plankton in its wake, a beautiful bright green flow of light.

We also got many fly fish around us—one of them decided to fly straight for me and landed on my shoulder.

Very surprising to be hit by something in the middle of a conversation during a dark night!

You and your crew are on your own.

About halfway through the trip, we took a swim on a quiet day.

It’s a strange feeling to bathe and dip in those waters, when the closest land was over a week of sailing in any direction.

ARC is one of the safest way to go across, since 200 boats leave on the same day towards the same island.

In theory, you’re never far from the others, but “not far” can be a few days away.

Sailing is like mountaineering—when you start your trip there’s no “pause button;” you need to make it to destination safely, and almost always without assistance.

Cars can break and stop, planes can land, divers can go back to the surface.

Sail boats must keep moving, from the moment they cast off until they are moored/secured.

Sailing is a truly immersive experience in the long run; constant motion for almost a month is a unique feeling.

Back to life on land

On the morning of the last day, our 23rd day, we were closing in on Rodney Bay, St Lucia, about to finish a long and great trip.

It’s hard to describe how much exitement and exhaustion affected us.

The ARC team welcomed us on deck with a glass of Rhum and a fruit basket!

Here are some of the weird things that happen when you reach land after 3+ weeks at sea:

- Urge to eat a burger. “Yes ma’am, I’ll take extra bacon!”

- Walking for more than 5 meters is strange, and going for a long walk is exhausting

- You can’t help holding on to something when cooking/going to the bathroom

- Feeling slightly off balance for the first days

- Getting ridiculously exciting about good coffee and fresh laundry

- Developing a suspicious attitude towards any sailing-related sound (must keep an eye out!)

- Talking to new people is such a novelty

- Opening your emails will be overwhelming

Closing thoughts

In 2009, finishing the Paris Marathon felt like a long-term project and effort, with weeks of preparation and a tough sustained effort on the day.

Sailing redefines “long term”—you live around sailing instead of running around your routine.

Both are extremely rewarding and quite humbling.

70% of the world is covered by water: make sure you get to experience life afloat.

It’s an uppercut outside of your comfort zone, feeling amazed and humbled at the same time.

We saw dead-flat water and 14+ meters high waves on the same trip.

Together we managed to get a 16-meter long toy across one of the largest oceans.

These days, most of my time and activities are on land.

But I still look forward to setting aside weeks and months in the years to come for sailing trips.

Have you ever embarked on a long-term adventure?

I’d love to hear your tales in the comments!

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Canada CHS update in the Marine GeoGarage

(currently under construction, upgrading to Google Maps API v3 as v2 is officially no more supported),

this info is primarily intended to our B2B customers which use our nautical charts layers

in their own webmapping applications through our GeoGarage API.

CHS raster charts coverage

47 charts have been updated (July 25, 2014)

1 chart has been withdrawn (1209 SAINT FULGENCE TO RIVIERE SHIPSHAW)

and 3 charts have been added (1201, 1360, 7950)

- 1201 SAINT-FULGENCE À / TO SAGUENAY NEW

- 1220 BAIE DES SEPT ÎLES

- 1234 CAP DE LA TÊTE AU CHIEN AU/TO CAP AUX OIES

- 1236 POINTE DES MONTS AUX/TO ESCOUMINS

- 1310 PORT DE MONTRÉAL

- 1311 SOREL-TRACY À / TO VARENNES

- 1312 LAC SAINT-PIERRE

- 1314 DONNACONA À/TO BATISCAN

- 1350A SOREL - TRACY AU/TO RUISSEAU LAHAISE

- 1350B RUISSEAU LAHAISE À/TO SAINT-ANTOINE-SUR-RICHELIEU

- 1350C SAINT-ANTOINE-SUR-RICHELIEU À/TO ÎLE AUX CERFS

- 1350D ÎLE AUX CERFS À/TO OTTERBURN PARK

- 1360 LAC MEMPHRÉMAGOG NEW

- 2006 UPPER GAP TO/À TELEGRAPH NARROWS

- 2018 LOWER GAP TO/À ADOLPHUS REACH

- 2028A LAKE SIMCOE

- 2028B LAKE COUCHICHING - LAKE SIMCOE TO/À COUCHICHING LOCK/L'ÉCLUSE DE COUCHICHING

- 2028C COOK'S BAY AND/ET HOLLAND RIVER

- 2064 KINGSTON TO/À FALSE DUCKS ISLANDS

- 2100 LAKE ERIE / LAC ÉRIÉ

- 2120 NIAGARA RIVER TO/À LONG POINT

- 2123 PELEE PASSAGE TO/À LA DETROIT RIVER

- 2250 BRUCE MINES TO/À SUGAR ISLAND

- 3050A KOOTENAY RIVER MILE 0 TO MILE 8.7

- 3050B SHEET 2 KOOTENAY RIVER MILE 8.3 TO MILE 16.5

- 3050C KOOTENAY RIVER MILE 15.8 TO 24.9

- 3050D KOOTENAY RIVER MILE 24.2 TO 29

- 3050E SHEET 5 KOOTENAY LAKE KUSKONOOK TO BOSWELL

- 3050F KOOTENAY LAKE RHINOCEROS POINT TO RIONDEL

- 3050G KOOTENAY LAKE RIONDEL TO KASLO

- 3050H KOOTENAY LAKE KASLO TO LARDEAU

- 3050I WEST ARM KOOTENAY LAKE PROCTOR LIGHT TO HARROP NARROWS

- 3050J WEST ARM KOOTENAY LAKE HARROP NARROWS TO NINE MILE NARROWS

- 3050K WEST ARM KOOTENAY LAKE NINE MILE NARROWS TO FIVE MILE POINT

- 3050L WEST ARM KOOTENAY LAKE FIVE MILE POINT TO NELSON

- 3050M WEST ARM KOOTENAY LAKE NELSON TO TAGHUM

- 3050N KOOTENAY RIVER TAGHUM TO CORRA LINN DAM

- 3441 HARO STRAIT BOUNDARY PASS AND/ET SATELLITE CHANNEL

- 3462 JUAN DE FUCA STRAIT TO/À STRAIT OF GEORGIA

- 3478 SANSUM NARROWS

- 3479 APPROACHES TO/APPROCHES À SIDNEY

- 3490 FRASER RIVER/FLEUVE FRASER - SAND HEADS TO/À DOUGLAS ISLANDS BC

- 3491 FRASER RIVER/FLEUVE FRASER - NORTH ARM AB

- 3526 HOWE SOUND

- 3536 PLANS STRAIGHT OF GEORGIA

- 3675 NOOTKA SOUND

- 3936 FITZ HUGH SOUND TO / À LAMA PASSAGE

- 4015 SYDNEY TO/À SAINT-PIERRE

- 4016 SAINT-PIERRE TO/À ST JOHN'S

- 4025 CAP WHITTLE À/TO HAVRE SAINT PIERRE ET/AND ÎLE D'ANTICOSTI

- 4047 ST PIERRE BANK BANC DE SAINT-PIERRE TO/AU WHALE BANK BANC DE LA BALEINE

- 4141A SAINT JOHN TO/À EVANDALE

- 4141B GRAND BAY TO/À EVANDALE INCLUDING/Y COMPRIS BELLEISLE BAY

- 4266 SYDNEY HARBOUR

- 4275 ST PETERS BAY

- 4335 STRAIT OF CANSO AND APPROACHES/ET LES APPROCHES

- 4379 LIVERPOOL HARBOUR

- 4404 CAPE GEORGE TO \ À PICTOU

- 4467 RUSTICO BAY

- 4625 BURIN PENINSULA TO/À SAINT-PIERRE

- 4626 SAINT-PIERRE AND/ET MIQUELON (FRANCE)

- 4643 ÎLE SAINT-PIERRE

- 4846 MOTION BAY TO/À CAPE ST FRANCIS

- 4847 CONCEPTION BAY

- 5024 NUNAKSALUK ISLAND TO / À CAPE KIGLAPAIT

- 5051 NUNAKSUK ISLAND TO/AUX CALF COW AND/ET BULL ISLANDS

- 6217A PTARMIGAN BAY AND/ET SHOAL LAKE

- 6217B PTARMIGAN BAY AND/ET SHOAL LAKE

- 6286A WHITEDOG DAM TO/À MINAKI - 1

- 6286B WHITEDOG DAM TO/À MINAKI - 2

- 7950 JONES SOUND NORWEGIAN BAY AND / ET QUEENS CHANNEL NEW

Note : don't forget to visit 'Notices to Mariners' published monthly and available from the Canadian Coast Guard both online or through a free hardcopy subscription service.

This essential publication provides the latest information on changes to the aids to navigation system, as well as updates from CHS regarding CHS charts and publications.

See also written Notices to Shipping and Navarea warnings : NOTSHIP

A tentacled, flexible breakthrough

From NYTimes by Katherine Harmon Courage

For years, roboticists have yearned to develop a flexible machine that can explore tight spaces, repair dangerous equipment and potentially even conform to the human body.

Yes, it is an octopus.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Satellites and seafood: China keeps fishing fleet connected in disputed waters

From Reuters by John Ruwitch

On China's southern Hainan island, a fishing boat captain shows a Reuters reporter around his aging vessel.

He has one high-tech piece of kit, however: a satellite navigation system that gives him a direct link to the Chinese coastguard should he run into bad weather or a Philippine or Vietnamese patrol ship when he's fishing in the disputed South China Sea.

By the end of last year, China's homegrown Beidou satellite system had been installed on more than 50,000 Chinese fishing boats, according to official media.

On Hainan, China's gateway to the South China Sea, boat captains have paid no more than 10 percent of the cost.

The government has paid the rest.

It's a sign of China's growing financial support for its fishermen as they head deeper into Southeast Asian waters in search of new fishing grounds as stocks thin out closer to home.

Government fuel subsidies make the trips possible, they added.

That has put Chinese fishing boats - from privately owned craft to commercial trawlers belonging to publicly listed companies - on the frontlines of one of Asia's flashpoints.

Most recently, they were a fixture around a Chinese oil rig positioned in disputed waters off Vietnam, where they jostled and collided with Vietnamese fishing boats for more than two months until China withdrew the drilling platform in mid-July.

Explanations for China's assertiveness in the South China Sea usually focus on the strategic significance of the waterway, through which $5 trillion in ship-borne trade passes each year, or Beijing's goal to increase its offshore oil and gas output.

Rarely mentioned is the importance of seafood to the Chinese diet, several experts said. A 2014 report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), for example, said China's per-capita fish consumption was 35.1 kg in 2010, nearly double the global average of 18.9 kg.

"Fish products are just so critical to China's way of life. I think this is something most people haven't factored into the equation when they've looked at these conflicts and disputes," said Alan Dupont, a professor of international security at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

"It's pretty clear that the Chinese fishing fleet is being encouraged to fish in disputed waters. I think that's now become policy as distinct from an opportunistic thing, and that the government is encouraging its fishing fleet to do this for geopolitical as well as economic and commercial reasons."

Distress signal

With 16 Chinese satellites in orbit above the Asia-Pacific at the end of 2012 and more planned, the 19-month-old Beidou system is a rival to the dominant U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS) and Russia's GLONASS. China's military is already a big user of Beidou, or Big Dipper.

It's unclear how often Chinese fishermen use Beidou to seek help. None of the fishermen Reuters interviewed in Tanmen said they had sent a distress call.

But fishermen could use the system to alert authorities if they had mechanical trouble or had a run-in with foreign maritime agencies, Chinese official media has said.

The push of an emergency button sends a message straight to the Chinese authorities, which because Beidou actively transmits location data, could pinpoint the exact whereabouts of a vessel.

Beidou's unique short messaging system also allows users to communicate with other fishermen, family or friends.

When Philippine authorities boarded a Chinese fishing vessel in May in a contested reef in the Spratlys, one of the region's main island chains, they quickly turned off the Beidou system, China's official Xinhua news agency said at the time.

A senior Philippine police official disputed that report, saying the boat had no satellite tracking device. Nine Chinese fishermen from the boat are awaiting trial in the Philippines for catching endangered turtles.

Zhang Jie, deputy director of the Hainan Maritime Safety Administration, a government agency, said he did not have accurate information on Beidou usage but added that fishermen were encouraged to fish in any waters that belonged to China.

At the same time, Zhang told Reuters he did not believe the government wanted them to seek conflict with other countries.

Other authorities in Hainan, such as the provincial fisheries office and the bureau which enforces fishing regulations, did not respond to requests for comment. Nor did the China Satellite Navigation Office, which runs Beidou.

The Foreign Ministry along with the State Oceanic Administration, which has overall civilian responsibility for maritime affairs including the coastguard and fishing vessels, also did not respond to requests for comment.

Xi backs fishermen

Since President Xi Jinping took power in March last year, Beijing has increasingly flexed its muscles in the South China Sea.

China claims 90 percent of the 3.5 million sq km (1.35 million sq mile) waterway, with the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan also claiming parts of the ocean.

China sent its sole aircraft carrier through the South China Sea for the first time in late 2013 while its coastguard has sought to block the Philippine navy from re-supplying a military outpost on a reef claimed by Manila in the Spratlys.

While some of China's actions have alarmed other claimants and drawn criticism from Washington, such as the placement of the oil rig off Vietnam, China says it has every right to conduct what it calls normal operations in its waters.

Only weeks after becoming president, Xi made what state media called a surprise visit to Tanmen, where he told fishermen the government would do more to protect them when they were in disputed waters.

Xi never elaborated, but a huge billboard near the port commemorates his visit, showing a picture of the president flanked by grinning fishermen with trawlers in the background.

Several fishermen from separate boats said the Hainan authorities encouraged fishing as far away as the Spratlys, roughly 1,100 km (670 miles) to the south.

The boat captain said he would head there as soon as his vessel underwent routine repairs.

"I've been there many times," said the captain, who like the other fishermen declined to be identified because he was worried about repercussions for discussing sensitive maritime issues with a foreign journalist.

Another fisherman, relaxing in a hammock on a boat loaded with giant clam shells from the Spratlys, said captains received fuel subsidies for each journey.

For a 500 horsepower engine, a captain could get 2,000-3,000 yuan ($320-$480) a day, he said.

"The government tells us where to go and they pay fuel subsidies based on the engine size," said the fisherman.

Added one weather-beaten captain: "The authorities support fishing in the South China Sea to protect China's sovereignty."

To be sure, they have other reasons to make the journey.

A study by the State Oceanic Administration said in October 2012 that fish stocks along the Chinese coast were in decline.

"Right now I would say competition for fishing resources is the main cause of tensions between China and regional countries," said Zhang Hongzhou, associate research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

David versus Goliath

At least one big Chinese fishing company is also flying the flag in disputed waters and benefiting from government assistance.

In late February, Shanghai-listed Shandong Homey Aquatic Development Co Ltd, which has annual seafood sales of $150 million, announced the launch of eight new 55-metre long (180-ft) trawlers from the port city of Dongfang on Hainan.

On its website, it said the move was a "response to the government's call to develop the South China Sea and safeguard national sovereignty".

Six weeks later, the Dongfang city government said Shandong Homey would get 2 million yuan ($322,500) for each boat in "renovation" grants, according to its website. Dongfang officials declined to comment.

Shandong Homey might need the money for repairs.

In late May, Vietnam's government accused a Chinese trawler of ramming and sinking a small Vietnamese wooden fishing boat near the Chinese oil rig in an incident captured on video.

China said the Vietnamese boat was being aggressive.

While footage of the May 26 incident is too blurry for the naked eye to determine the number on the Chinese ship's hull, Vietnam's coastguard said it was #11209.

Dang Van Nhan, 42, the captain of the sunken boat and who was rescued along with nine crew, told Reuters during an interview in the coastal Vietnamese city of Danang that it was #11202, saying he got a clear look.

The Dongfang city government website lists vessels #11209 and #11202 and six others as Shandong Homey's eight new boats.

In the Dongfang harbor, several Shandong Homey boats lay anchored including vessels #11209 and #11202. Both have the same features as the trawler in the video.

Shandong Homey declined telephone and email requests to comment.

One crew member at the port said the fleet returned to Dongfang in early June but then refused to say anything more.

Several Shandong Homey employees later surrounded a Reuters reporter and demanded to know why he was asking about the boats.

They then turned him over to police, who briefly detained him.

($1 = 6.2025 Chinese Yuan)

Links :

- National Interest : China’s 50,000 Secret Weapons in the South China Sea

- Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific (book by Robert D. Kaplan)

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

How Lego figures and rubber ducks reveal ocean secrets

From BBC by Richard Fisher

Weird and wonderful objects washed up on the world's beaches shed more light on the workings of the ocean currents than you might think.

Marooned on an island, if you threw a message-in-a-bottle into the ocean, would you be saved?

The answer, according to researchers, depends on where you are.

An interactive map shows how floating objects dropped into the ocean travel over the years.

So drop a bottle off the east coast of the US, for example, and if you’re lucky, it may have reached France, Spain or North Africa after a couple of years – but equally it could have turned around and been trapped in an ocean gyre circling around the centre of the Atlantic.

Objects can flow around the ocean for years or even decades before they reach shore.

In April, a message-in-a-bottle turned up off the coast of Norway after a staggering 101 years at sea.

Decade-plus journeys aren’t unusual.

On New York beaches, for instance, passers-by have reported finding treasure that appears to have been away from land for years, including unusual animal bones, dentures and even a robot hand.

And this week BBC Magazine reported on how tiny pieces of Lego have been continually washing up on the shores of Cornwall in the UK since 1997.

These strange objects enter the sea via beach litter, rivers and

shipping containers lost overboard.

Not only do they provide a curious

and occasionally disturbing record of humanity’s effects in this era,

they can also provide researchers with surprising insights into the vast

ocean currents that sweep the globe.

A 2014 survey by the World Shipping Council suggests around 2,683 containers were lost at sea per year between 2011 and 2013.

The real figure could well be more, as many go unreported and no single database keeps track.

Perhaps

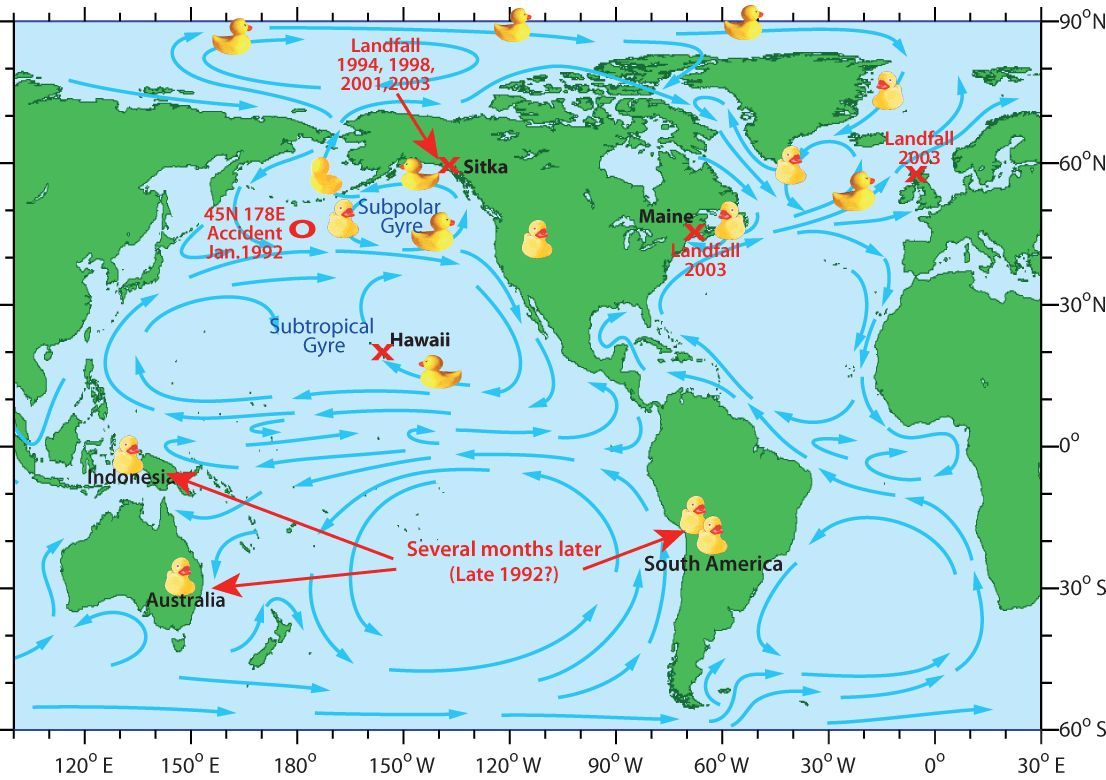

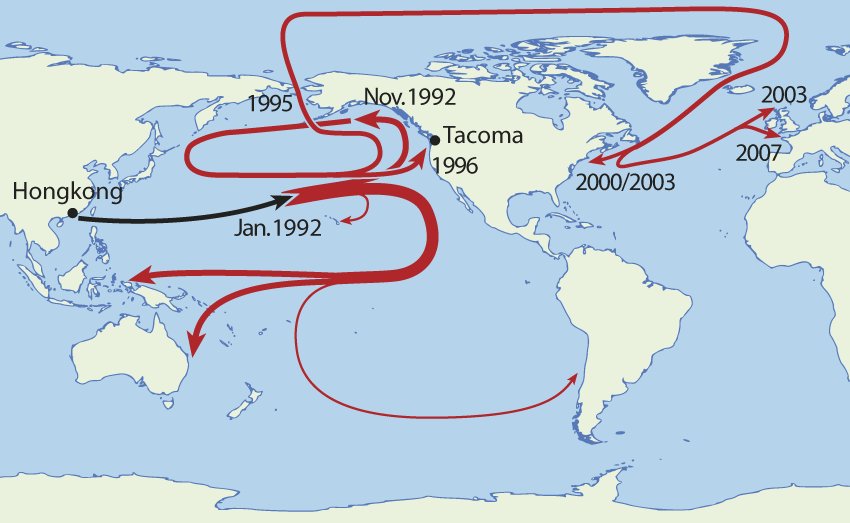

the most famous case of drifting ephemera was a fleet of more than

28,000 rubber ducks and other bath toys, known as the Friendly Floatees.

The ducks accidentally fell into the Pacific from a container ship en

route from China to Seattle in 1992, and were tracked by the

oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmayer, who called on beachcombers to report sightings.

The Floatees spent over a decade circling on the sea.

What was perhaps

most striking was just how far the ducks travelled, with some ending up

in Europe and Hawaii, and confirmed sightings continued until at least

the mid-2000s.

(See the path the rubber ducks took here.)

This hinted that floating objects take a much longer journey between oceans than previously realized.

In 1992, around 29000 rubber ducks fell off a cargo ship in the Pacific Ocean.

This is where they made landfall.

In 2012, Erik van Sebille of the University of New South Wales in Australia and colleagues confirmed this suspicion by using a network of around 20,000 satellite-tracked ‘drifter’ buoys.

They found that there are six major patches of plastic garbage in the oceans: five in the subtropical seas, and one more high up in the Arctic Barents Sea that was previously unknown.

And crucially, this work revealed how the plastic migrates between the patches over long timescales.

“They are much more connected than ever envisioned,” he says.

“They leak.”

This research inspired them to create their interactive map.

According to van Sebille, in some regions of the North Pacific there's potentially more weight in plastic than there is in life.

A lot is too buoyant to sink. “It’s almost like the turd that won’t flush,” he laughs.

Contrary to popular belief, however, the stuff does not exist as giant islands.

It is dispersed and much of it is ‘microplastic’ – tiny, eroded fragments – and so it’d be near-impossible to go out there and sweep it up.

The danger to wildlife is clear.

Since most of this circulating material does not decompose easily, eventually it may even wind up in the rock record, deposited on beaches or in the deep ocean inside fish poo after they have digested it.

Indeed, US researchers recently described a new type of solid rock found in Hawaii containing plastic bags, rope and bottle tops.

They called it “plastiglomerate”.

Peer closer, and they might even get lucky and find whole objects, such a Barbie arm, a pair of dentures – or even a message-in-a-bottle.

Links :

- io9 : Track the path of any object drifting on the ocean

- BBC : The Cornish beaches where Lego keeps washing up

- The Telegraph : Millions of tiny Lego pieces lost at sea more than 17 years ago are still washing up on Cornish beaches

- GeoGarage blog : It's amazing what a duck can teach you

Monday, July 28, 2014

Boom! There goes the neighborhood

This is a terrible idea.

Suppose someone was detonating a stick of dynamite in your neighborhood.

Acoustic noise, whether it’s seismic testing for oil and gas or sonar exercises conducted by the Navy, creates what some biologists call an “acoustic smog.”

This smog interferes with the way marine mammals perceive the world. In a way, it’s like they go blind.

Whales use sound to eat, hunt, find mates, navigate, and communicate with their young and the rest of their pod.

Sonic booms jeopardize all of those activities.

National Geographic reports that the government's own estimates have the noise pollution injuring (potentially killing) more than 138,000 marine mammals, and disrupting the migration, feeding, and reproductive behaviors for 13.6 million others.

Seismic testing produces a cacophony nearly on par with exploding dynamite.

In fact, the industry actually used to employ dynamite in its search for undersea oil and gas deposits before airguns became a safer alternative.

(Safer for workers, that is. Not whales.)

“Whales use sound for virtually everything they do to survive and reproduce in the wild,” says Michael Jasny, a marine mammal expert with NRDC (which publishes OnEarth), “and when we make sounds on the order of an industrial seismic survey, we are fundamentally compromising the foundation on which marine life depends.”

And it’s not just about the nearby booms.

Sonic waves pervade through entire ocean basins.

In one study, scientists found that a single seismic test can drown out the low-frequency calls of endangered baleen whales for 10,000 square nautical miles—that’s larger than the state of West Virginia.

Worse still, airguns can make endangered fin and humpback whales fall silent over areas of the ocean 10 times larger than that.

OK, so a whale’s survival and sense of serenity doesn’t tug at your heartstrings, but you should know that opening up the East Coast to offshore drilling would hit you in your stomach, too.

Seismic surveys, studies show, negatively affect the fishing industry, reducing catch rates for cod, haddock, and rockfish.

And I don’t need to remind you that the fossil fuels we haul out of the ocean exacerbate climate change, right?

Offshore drilling, lest we forget, also risks oil spills that devastate whale, fish, and human communities.

"The use of seismic airguns is [the] first step to expanding dirty and dangerous offshore drilling to the Atlantic Ocean, bringing us one step closer to another disaster like the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill," Claire Douglass of Oceana told the Balitimore Sun.

Now that the path to drilling in the Atlantic is open, the fight to save marine life would require stopping oil and gas companies from getting permits for seismic testing and eventually, drilling.

And if that doesn’t work, environmentalists might have to appeal to the courts.

Remember, the oil and gas industry isn’t the only one who knows how to bring the noise.

BOOM go lawsuits, too.

- The Guardian : Whales under threat as US approves seismic oil prospecting in Atlantic

- Southern Studies : The money behind Big Oil's win on Atlantic drilling

- Huffington Post : Obama Administration to Whales, Dolphins: You Go Deaf, We'll Get Oil

- Newsweek : Whales are being killed by noise pollution

- Scientific America : Does military sonar kill marine wildlife?

- OceanLeadership : Research into marine mammals’ responses to sound