- YouTube : Watch Part 2 - Islands

Saturday, March 26, 2022

The hidden world of seamounts

Friday, March 25, 2022

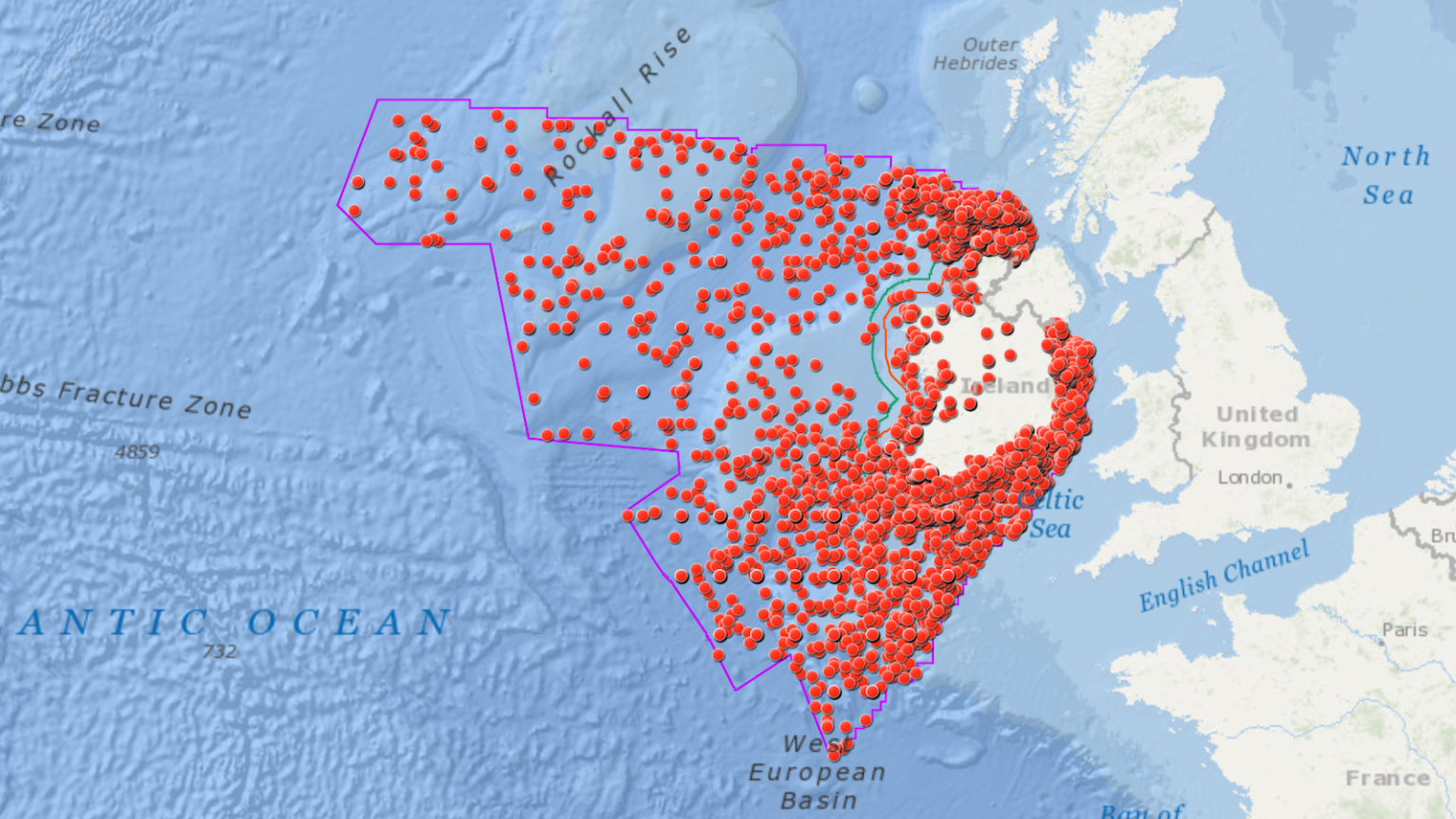

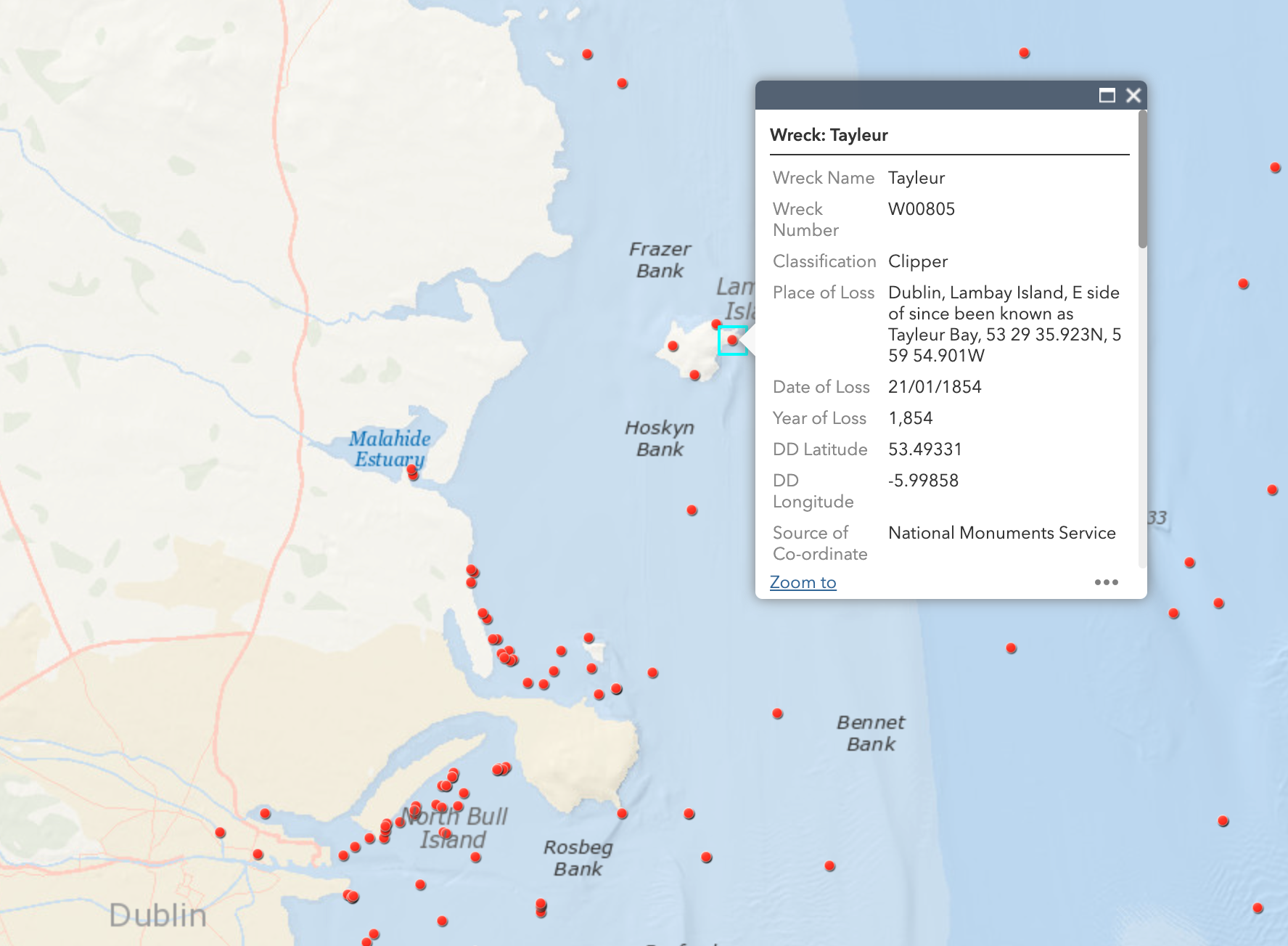

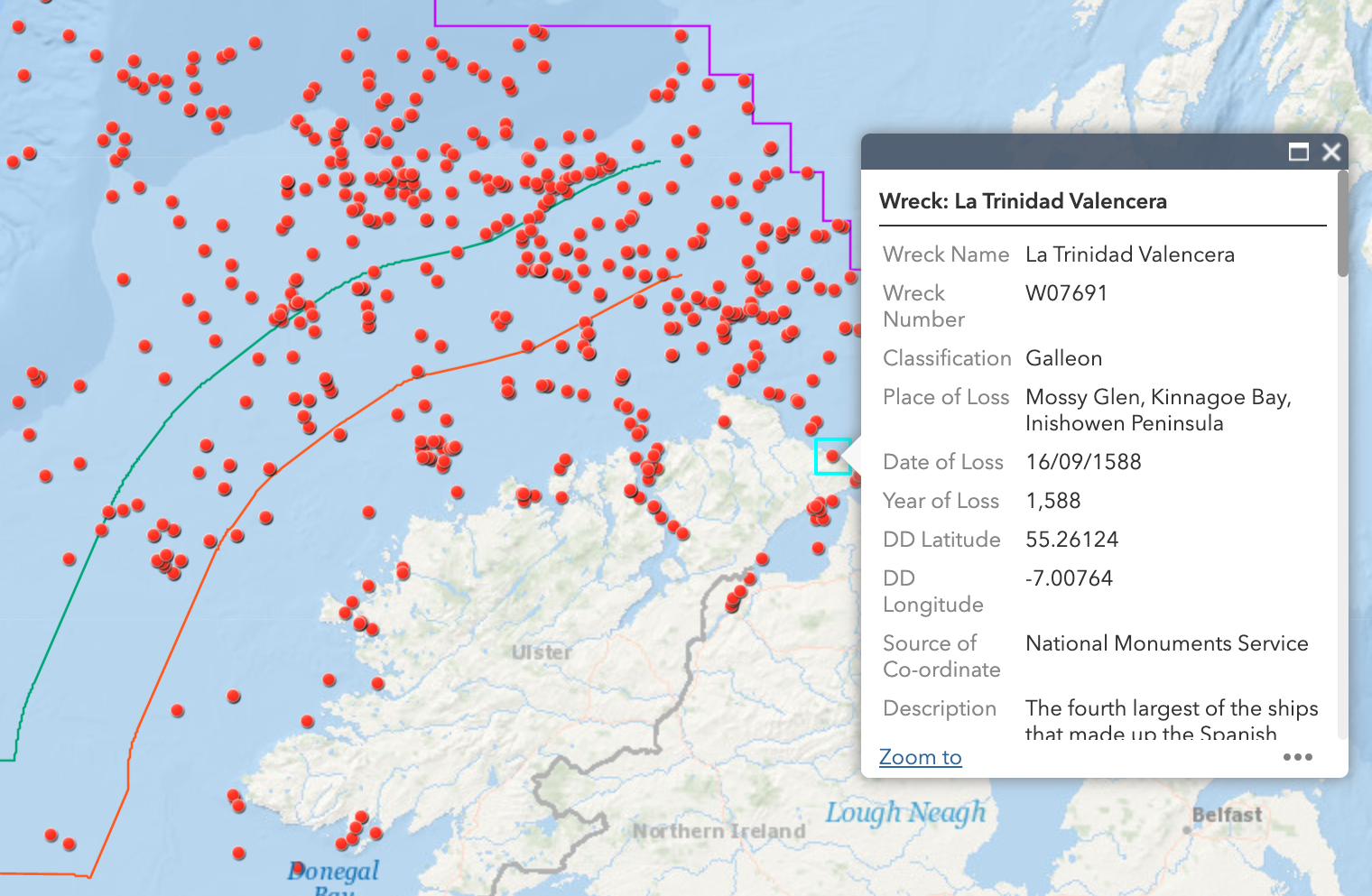

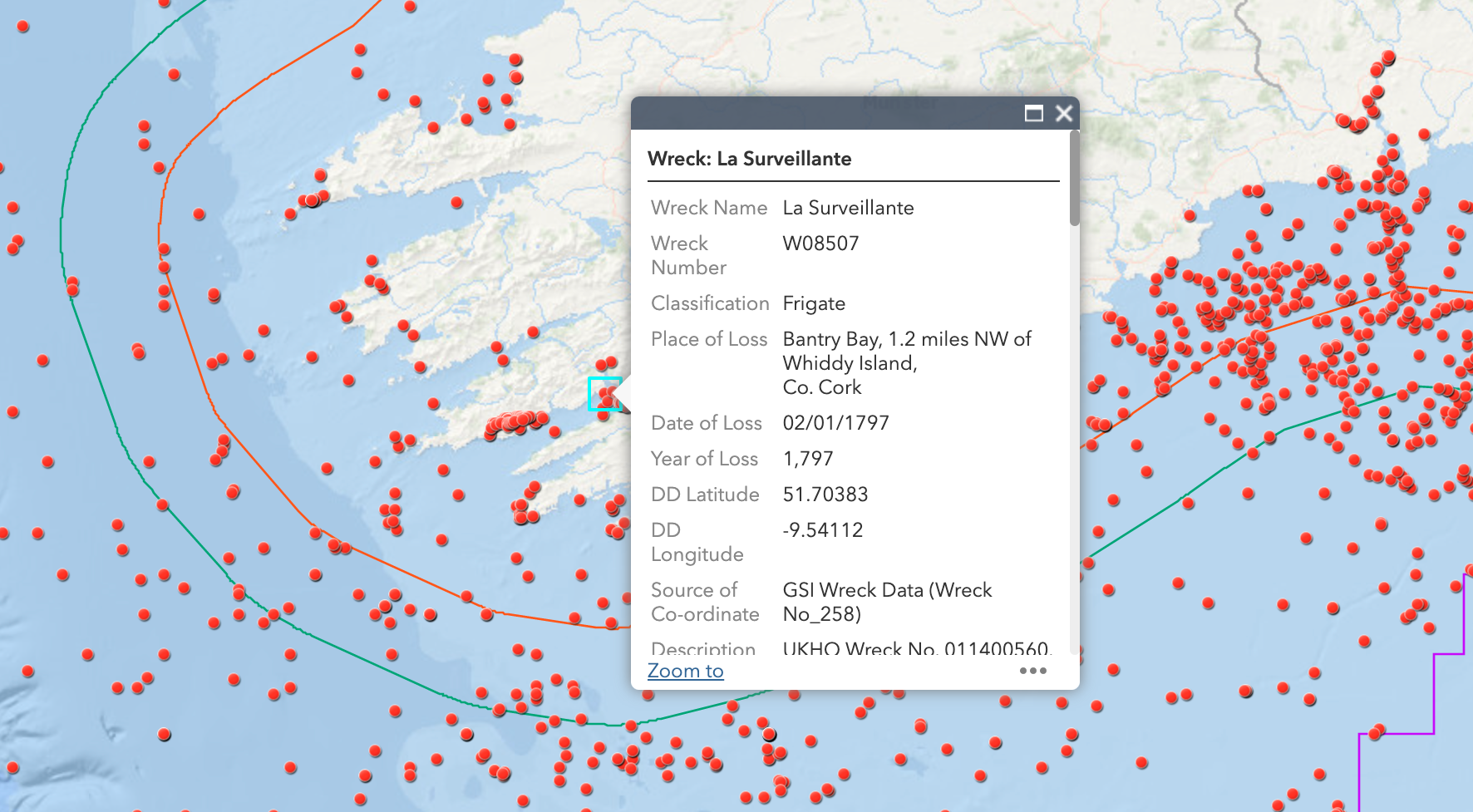

An interactive map of Irish shipwrecks, littered with thousands of stories

After more than a century in cold and dark Antarctic waters, a legendary ship was rediscovered last month. Ten thousand feet below the frozen surface of the Weddell Sea, an underwater drone lit up the wreck of the three-master that had brought Sir Ernest Shackleton to the South Pole.

Trapped and crushed

Shackleton had wanted his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-17) to be the first to cross the icy continent over land. Instead, his ship got trapped and then crushed by pack ice.

Because of their undaunted perseverance, Shackleton’s expedition is considered the last of the “heroic” explorations of the South Pole — a quality quite literally highlighted by the search team’s sub as it illuminated the ship’s name, still perfectly legible on its stern: ENDURANCE.

Shipwrecks are stories without happy endings.

Three million shipwrecks

In total, the NMS’s underwater archaeological unit has documented almost 18,000 wrecks — and not just ships, nor only at sea.

Ireland’s shipwreck register spans the entire maritime history of Ireland, from the aforementioned prehistoric logboat and medieval trading vessels to warships, ocean liners, and even humble fishing boats, such as the one that went down in January 2017 — fortunately without loss of life.

Armada adventure ends in Ireland

As the map shows, a remarkable portion of those wrecks is unknown — that is, the NMS knows of the wreck but knows little or nothing about it.

By volume — and undoubtedly by a few other measures too — World War I was the most eventful period in Irish marine history.

War is not a precondition for disaster, though.

Not all shipwrecks stay shipwrecked

Not all shipwrecks stay that way.

For more shipwreck stories, go visit Ireland’s “Wreck Viewer”.

- National Monuments Service : Wreck viewer

Thursday, March 24, 2022

11 of History’s most famous sea voyages

/ Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images

From Mental Floss by Julie Fogerson

Throughout history, sea travel in the name of exploration, trade, and research has provided a watery road to modern globalism.

We have always wondered at the waves, finding ways to wade deeper and wander further: The world’s oldest known boat, the Pesse canoe, dates to around 8000 BCE; there is evidence Egyptians began sailing around 4000 BCE; and the Phoenicians are credited with ship-building expertise that allowed them to circumnavigate Africa in 600 BCE.

Here are 11 incredible sea voyages and voyagers that helped advance our understanding of the world.

1. Leif Erikson’s Voyage to North America // c. 1000

Born in 970, Norse explorer Leif Erikson was the second son of Erik the Red, a native of Iceland who colonized Greenland around 980.

According to Viking sagas written a few centuries after the events, Erikson heard about an unfamiliar land to the west of Greenland and went to investigate it, eventually landing with a small crew on the northern peninsula of Newfoundland.

Though the settlement didn't last long, archaeological evidence and the sagas suggest that Erikson’s Vikings were the first Europeans to set foot in North America.

2. Zheng He’s Seven Diplomatic Voyages // 1405-1433

Beginning life as Ma Sanbao in 1371, Zheng He grew up in a prosperous Muslim family in China.

When he was about 10, he was captured during Emperor Hong Wu’s attack on his city and made to serve as a court eunuch.

He eventually rose up the ranks, becoming a valued diplomat and commander of the Ming Dynasty’s navy.

He embarked on his first voyage in 1405, commanding the emperor’s enormous fleet of “treasure ships.” Some of the hundreds of vessels were 400 feet in length, and the whole armada was crewed by 28,000 sailors.

During his seven expeditions to lands surrounding the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, Zheng He helped spread China’s culture and political influence.

Chinese emigration increased, as did tributes to Chinese leaders.

Upon Zheng He’s death in 1433, and the establishment of a new emperor, the expeditions’ ships and logs were destroyed.

This ended the “golden era” of Chinese sea exploration, making room for Europeans.

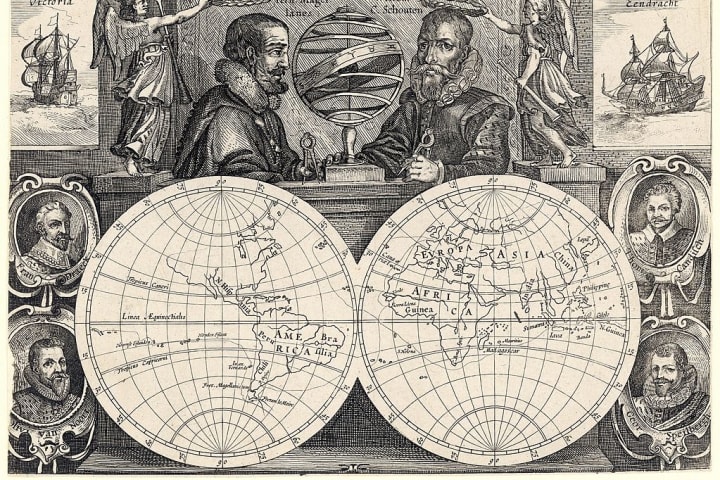

Schouten are both holding protractors above the maps.

Portuguese sailor Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage is credited with being first to circumnavigate the globe.

In 1519, approximately 260 men and five shipsset sail from Spain, searching for a western route to the Spice Islands (in modern-day Indonesia).

Magellan named the Pacific Ocean (Pacific means “peaceful”) and discovered the Strait of Magellan at the bottom of South America by accident (it's still used to this day for navigation between the Atlantic and Pacific).

While Magellan deserves his due for masterminding the voyage, a poison arrow ended him in 1521 upon his arrival in the Philippines.

According to some historians, Enrique, an enslaved Malay man in Magellan’s crew, completed the circumnavigation first, albeit over more than one voyage, before Magellan’s remaining 18 crewmembers made it back to Spain in 1522.

4. “Pirate Queen” Grace O’Malley’s Defense of Ireland // c. 1546-1586

Irish seafarer Gráinne Ní Mháille, a.k.a. Grace O’Malley, a.k.a. Ireland’s pirate queen, is considered one of the last Irish clan rulers to fight against English domination in Ireland.

Born in 1530, Grace began her high-stakes, high seas career at age 11, when Ireland was ruled by about 40 Gaelic clans (the O’Malley clan motto was “powerful by land and by sea”).

When her father died, it was Grace and not her elder brother who became clan leader, managing two galleys, 20 ships, and more than 200 men to plunder coastal strongholds and defend against English encroachment.

When Grace negotiated the release of prisoners and seized land with Queen Elizabeth I, she demanded an audience as an equal.

A respected matriarch in her time, she was omitted from history for centuries.

Today, she is celebrated for her leadership at sea.

5. The Sea Venture’s Adventure // 1609-1610

The Sea Venture has been dubbed “the shipwreck that saved Jamestown” and inspired William Shakespeare while he wrote The Tempest. The ship, part of a convoy sent from England in 1609, was supposed to resupply the desperate Virginia colony.

But when it sailed straight into a hurricane and rammed a reef around then-uninhabited Bermuda, the Sea Venture’s adventure appeared to be over.

However, all 150 souls aboard survived by swimming to shore and set about building two new ships to take them the rest of the way.

The castaways arrived in Jamestown about 10 months later.

Their story of survival not only restored England’s desire to make its American colony a success; it also led to the second English colonyestablished in the Americas—not in New England, but in Bermuda.

6. The Mayflower’s Arrival in North America // 1620

The Mayflower, a second-hand merchant ship carrying 102 passengers, left Plymouth, England, for North America in 1620.

Forty of the passengers were Protestant separatists (later known as Pilgrims) who sought to establish a colony in America where they could practice their religion freely.

They had permission to settle anywhere on the coast between the Chesapeake Bay and New York Harbor.

But two miserable months after launch, the Mayflower landed in New England, about one degree of latitude north of where it was meant to be.

The colonists named the new settlement Plymouth, drafted a document to set guidelines for self-governance, and launched a historic experiment in democracy and religious freedom.

7. The Three Voyages of James Cook // 1768-1780

James Cook vowed to sail “as far as I think it possible for man to go” and ended up mapping more territory than any other mariner of his era.

He joined the British Royal Navy in his twenties, and in 1767 produced a chart of Newfoundland that was so accurate it was still being used in the 20th century.

Cook led his first exploratory expedition in 1768, destined for the South Pacific to observe the transit of Venus and to chart New Zealand, Tasmania, and parts of Australia.

He came quite close to spotting Antarctica during a second circumnavigation to explore and map several South Pacific islands.

In 1776, on his third and last epic voyage, Cook came within 50 miles of the western entrance to the Northwest Passage in the Bering Strait.

He was the first European commander to visit Hawaii, where friction increased between his crew and the local people; Cook was killed by Native Hawaiians in 1779 and the expedition concluded without him the following year.

Among his countless observations and discoveries, Cook found that fresh fruits seemed to prevent scurvy, without knowing just how the remedy worked.

8. The Wreck of the Whaler Essex // 1820

Another voyage serving up literary inspiration is the tale of the Essex.

An 87-foot whaling ship, the Essex was built of incredibly strong white oak and fitted for a 2.5-year voyage.

It left Nantucket in 1819, made its way around Cape Horn, and headed into the South Pacific.

On November 20, 1820, an 85-foot sperm whale rammed the ship twice and caused it to sink, serving some small measure of justice on behalf of his species (numbering 300,000 today from an estimated 1.1 million prior to whaling).

While the 20 crewmembers initially survived, they drifted in boats across the open ocean for three months and eventually resorted to cannibalism.

Only eight made it home.

Herman Melville based the climactic scene in Moby-Dick on the Essex tragedy.

9. Charles Darwin’s Voyage on the HMS Beagle // 1831-1836

/ The Print Collector/Getty Images

Charles Darwin said his education “really began aboard the Beagle.” A fresh university graduate at age 22, Darwin paused his planned career as a clergyman and joined the Beagle as its naturalist.

Setting sail in 1831, the ship’s mission was to journey around the world, surveying the South American coast and conducting chronometric studies.

Time spent in the Galápagos truly informed Darwin’s theories on evolution, providing an opportunity to observe species development in an isolated environment.

Darwin also considered coral, recording geological observations about islands and coastlines.

And the Beagle, commanded by Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy, achieved its goal of accurately charting the coast of South America, including the Strait of Magellan's dangerous shoals.

10. Ernest Shackleton’s Miraculous Endurance // 1914-1916

Anglo-Irish mariner Ernest Shackleton first sailed to Antarctica in 1901 on a mission to reach the South Pole, which ended with a bad case of scurvy.

He would come within 97 nautical miles of the pole on his second expedition.

But it was his third venture aboard the Endurance for which he is most famous.

In 1914, he led a crew of 28 men intending to be the first to cross Antarctica by land, but the ship became trapped in pack ice for 10 months and sank on November 21, 1915.

The crew set up camp on ice floes, drifted on treacherous seas, and washed up on an uninhabited polar island.

Shackleton and five men then sailed 800 miles across the planet’s most rambunctious seas for rescue.

All hands succeeded in their revised mission: survival.

Shackleton’s story serves as a lesson in leadership against all odds and overcoming outrageous obstacles.

11. Thor Heyerdahl’s Maritime Experiment in the Kon-Tiki and More // 1947-1978

Thor Heyerdahl, a Norwegian ethnologist, mounted several transoceanic scientific expeditions.

His expeditions on the Kon-Tiki, a balsa-wood raft launched in 1947, and Ra, a copy of an Egyptian reed boat crewed in 1969, proved the possibility of ancient contact between distant civilizations.

Leaving from Peru, Kon-Tiki reached the South Pacific three and a half months later, lending evidence to the theory that pre-Columbian sailors could have navigated across the Pacific.

Ra sailed from Morocco to within 600 miles of Central America and hinted at the possibility that Egyptian mariners could have influenced pre-contact cultures.

And in 1977-1978, sailing a reed boat named the Tigris, Heyerdahl suggested that ancient Sumerians could well have reached southwest Asia.

His thought-provoking theories are still being debated.

- GeoGarage blog : How Magellan circumnavigated the globe / Embarking on Magellan and Elcano's first journey around the ... / Mystery of island visited by 15th Century Chinese explorer ... / 400 years on, the Pilgrims get a reality check / James Cook: The Voyages /

Capt. James Cook raised an ocean of knowledge / The story of a ship that changed the world/ The Whale: the terrifying real voyage that inspired Moby-Dick / Sunken whaling ship of 'Moby Dick' captain found / Book review : Melville's whale was a warning we failed to heed / Shackleton's Endurance: Modern star maps hint at famous ... / New proof for Kon-Tiki theory – archive, 1953 / The Tangaroa Expedition (The Kon-Tiki ...

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

Ancient documents suggest Italian sailors knew of America 150 years before Christopher Columbus

Transcribing and detailing a, circa, 1345 document by a Milanese friar, Galvaneus Flamma, Medieval Latin literature expert Professor Paolo Chiesa has made an “astonishing” discovery of an “exceptional” passage referring to an area we know today as North America.

According to Chiesa, the ancient essay – first discovered in 2013 – suggests that sailors from Genoa were already aware of this land, recognizable as ‘Markland’/ ‘Marckalada’ – mentioned by some Icelandic sources and identified by scholars as part of the Atlantic coast of North America (usually assumed to be Labrador or Newfoundland).

“We are in the presence of the first reference to the American continent, albeit in an embryonic form, in the Mediterranean area,” states Professor Chiesa, from the Department of Literary Studies, Philology and Linguistics at the University of Milan.

Galvaneus was a Dominican friar who lived in Milan and was connected to a family which held at the lordship of the city.

“These rumors were too vague to find consistency in cartographic or scholarly representations,” the professor states, as he explains why Marckalada wasn’t classified as a new land at the time.

He adds: “What makes the passage (about Marckalada) exceptional is its geographical provenance: not the Nordic area, as in the case of the other mentions, but northern Italy.

“The Marckalada described by Galvaneus is ‘rich in trees’, not unlike the wooded Markland of the Grœnlendinga Saga, and animals live there.

“These details could be standard, as distinctive of any good land; but they are not trivial, because the common feature of northern regions is to be bleak and barren, as actually Greenland is in Galvaneus’s account, or as Iceland is described by Adam of Bremen.”

“I do not see any reason to disbelieve him,” states Professor Chiesa, who adds, “it has long been noticed that the fourteenth-century portolan (nautical) charts drawn in Genoa and in Catalonia offer a more advanced geographical representation of the north, which could be achieved through direct contacts with those regions.

Cronica universalis, written in Latin, is still unpublished; however, an edition is planned, in the context of a scholarly and educational program promoted by the University of Milan.

- Phys : Italian sailors knew of America 150 years before Christopher Columbus, new analysis of ancient documents suggests

- The Economist : A monk in 14th-century Italy wrote about the Americas

- QS Studt :Word of Viking Settlements in North America Reached Italy 150 Years before Columbus

- Medievalists : Italians knew about North America in the 14th century, historian finds

- Modern Science : A Friar Wrote About North America 150 Years Before Columbus Got Ther

- Reference: “Marckalada: The First Mention of America in the Mediterranean Area (c. 1340)” by Paolo Chiesa, 16 July 2021, Terrae Incognitae. DOI: 10.1080/00822884.2021.1943792

- DailyMail : Italian sailors knew about North America 150 years BEFORE Christopher Columbus discovered the continent, researchers claim

- GeoGarage blog : How a faulty map led to the discovery of America / Martin Behaim's Erdapfel, 1492 / A map that may have led Columbus to America is finally being ... / Map Lab uncovering hidden text on a 500-year-old map that ... / Did Marco Polo "discover" America?

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

Everything you ever wanted to know about SAR satellite data and the ecosystem but were afraid to ask

The adoption of Earth Observation satellite technologies is accelerating.

More and more companies and institutions are using satellite imagery to better understand the world and more closely observe relevant changes.

However, those actors are also coming to the realization that optical satellite systems have their limitations.

The biggest barriers to the use of satellite imagery are cloud cover and limited usability of the data at night—of course, earthquakes or floods can happen at any time, regardless of the weather or time of the day.

Fortunately, optical images are not the only way to visualize the earth’s surface from a satellite. Synthetic Aperture Radar, or SAR, is a completely different way of generating a picture, actively ‘illuminating’ the ground rather than utilizing the light from the sun (as with optical images).

SAR satellites beam radar waves to the surface of the earth and map the reflected signal.

The system can penetrate clouds, see beneath tree canopies, and work in all weather conditions.

SAR market and demand

In recent years, SAR images have played an increasingly important role in international emergency events, such as the drone attacks against Saudi oil installations in 2019 and the Ever Given ship blocking the Suez Canal in 2021.

According to the market report from Mordor Intelligence, the Global SAR Market was valued at $3,3 billion in 2020, and it is expected to reach $6,5 billion by 2026—representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.6% during the period of 2021–2026.

The 11th Edition of NSR’s Satellite-Based Earth Observation reports that the sale of SAR data and derived products is going to see significant growth in annual global revenues, from $700M in 2018 to over $1.7B by 2028.

Imagery sales and information products are predicted to dominate, responsible for 63% of SAR revenues in this timeframe.

Very-high-resolution imagery (<0.5m) has become the fastest developing market, while high-resolution (0.5-1m) occupies the biggest part of the current market.

However, not all the SAR satellites are able to follow this wave of growth.

According to NSR’s report, medium resolution (1-5m) market share began to decrease after 2017.

Low resolution, meanwhile, presents limited commercial value.

It seems that the providers of low-resolution SAR data will need to adapt as high-resolution commercial data brings much more value to clients.

The largest demand for SAR satellite images comes from the Military and Defense Sector.

The biggest individual buyer of SAR satellite image also comes from the Military and Defense Sector: the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA).

Besides the Military and Defense Sector, the Financial and Insurance Sectors are also rapidly growing markets, with a CAGR of 14%.

Traditionally, SAR satellite constellations are based on government programs building large, heavy, and costly satellite units and sensors, offering fairly low revisit rates and requiring significant investment—such as the Sentinel-1 mission.

The history and development of SAR

SAR is not a new technology; it started in the US nearly 70 years ago. However, the application of SAR has only become popular over the past decade.

1951–2000: Limited technology in Defense sector

Radar has a history stretching back nearly 100 years.

Imaging radar, meanwhile, attempts to form an image of such an object.

In 1960, the first SAR experiment was successfully completed in Washington, and in 1978, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched the first SAR satellite (SEASAT-1).

However, from 1990 to 2000, SAR technology started to come out from the laboratory, and Europe, Canada, Russia, Japan, and many other countries started to build SAR satellites.

1995–2013: Rapid development of technology and the beginning of commercial applications

For years, SAR technology has been limited to military and research domains, but the first country to commercialize SAR satellite imagery was Canada.

The first sub-meter radar imagery for commercial applications was launched in 2007.

While the commercialization of SAR satellites developed slowly, a breakthrough occurred in 2014, when the European Space Agency launched the first of its Sentinel-1 satellites, as the first part of the Copernicus satellite constellation.

At the same time, the ESA Technology Transfer and Business Incubation Office initiated its ESA Business Incubation Centres (ESA BICs) to turn space-connected business ideas into startups.

With the policy of free data and support, many SAR startups grew rapidly in this period, especially those using InSAR technology.

Sentinel-1’s freely available 10m imagery, with its 6–12-day revisit, proved quite satisfactory for the existing ecosystem of SAR data users.

Around 2015, the new era of the space sector started to emerge with the development of microsatellite constellations.

Traditionally, the building costs of large satellites could easily reach hundreds of millions of dollars to ensure component stability.

In 2014, ICEYE was founded in Aalto University, Finland, and in 2018, the 70kg ICEYE-X1 was launched as the first satellite under 100 kg to carry a SAR sensor—as well as the first Finnish commercial satellite.

In the US, the SAR startup Capella Space was founded in 2016.

SAR has been used in a wide range of applications, from studying Antarctic icebergs and detecting changes in habitat, to mapping the effects of natural or human disturbance.

1. Emergencies:

On August 5th, 2020, a large explosion occurred in the Port of Beirut, equivalent to 100 tons of TNT.

2. Maritime and coastal zone monitoring:

On July 25th, 2020, a ship ran aground south of Mauritius, and spilled at least 1,000 tons of oil into the Indian Ocean.

3. Land monitoring:

A ground deformation analysis was conducted for approximately three years (July 2018 to June 2021) in Guatemala City and its suburbs by SAR startupSynspective.

4. Agriculture and vegetation:

In Peru, canopy formation, density, and the growth rate of asparagus crops have been monitored by Sentinel-1 satellite since 2019.

There are two groups of key players in the SAR satellite industry: Governments and startups. However, they are playing different games.

Government groups tend to focus on large satellites.

The United States, the traditional top player in the aerospace industry, had a big advantage in SAR technology—until European players joined the game.

Since Sentinel-1B stopped working at the end of 2021, faith in large satellites has also been lost to an extent. Pressure is also coming from the small satellite startups—ICEYE from Finland and Capella Space from the US are becoming the main players in this game.

Compared to the wide range of uses for optical data, there are still only a few applications of SAR data in the commercial space.

For the industry, emergency response offers big opportunities for new startups.

At the same time, the international political atmosphere hasn’t been this tense for a long time.

However, the opportunities for new entrants in the space are decreasing.

- Smaller and lighter: The R&D and investment costs of large and medium-sized satellites are prohibitive for a startup. Therefore, the only opportunities left for startups are small satellites (under 200kg).

- Constellations: Every startup has a plan to build a large satellite constellation. But the one who makes it will be the final winner. Talk is cheap; show me the satellite!

- Easier analysis, simpler processing: Analysis of SAR data requires a lot of time, expertise, and computational tools. Industrial image organizing and processing software was originally developed for the human eye—for optical not radar—leaving SAR lagging behind and more expensive. Making analysis easier and simplifying the processing chain will attract more students and players to the SAR industry.

- From upstream to downstream: Increasingly, satellite manufacturers hope to do more in downstream applications—and vice versa.

“A picture is worth a thousand words”, and it is certainly the case for satellite data.

- BAIR : Accelerating Ukraine Intelligence Analysis with Computer Vision on Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery

- Reuters : Canada's MDA providing Ukraine with satellite imagery to fight Russia

- GeoGarage blog : maritime activity from Sentinel-1 SAR instrument / This radar image highlights the growth of the small satellite ... / Iceye releases dark vessel detection product / Visualizing shipping lanes from Sentinel-1 / Iceye releases dark vessel detection product

Monday, March 21, 2022

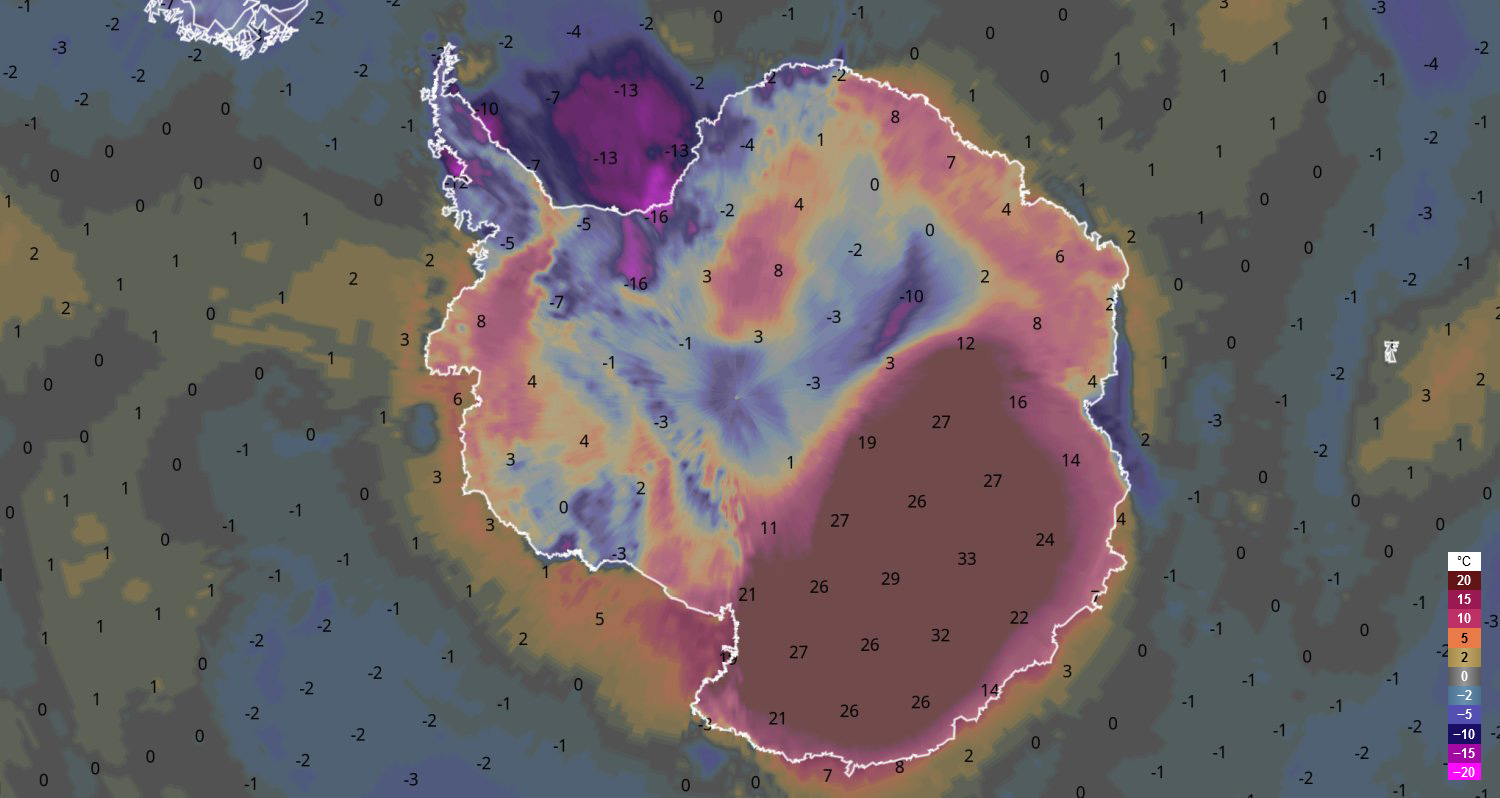

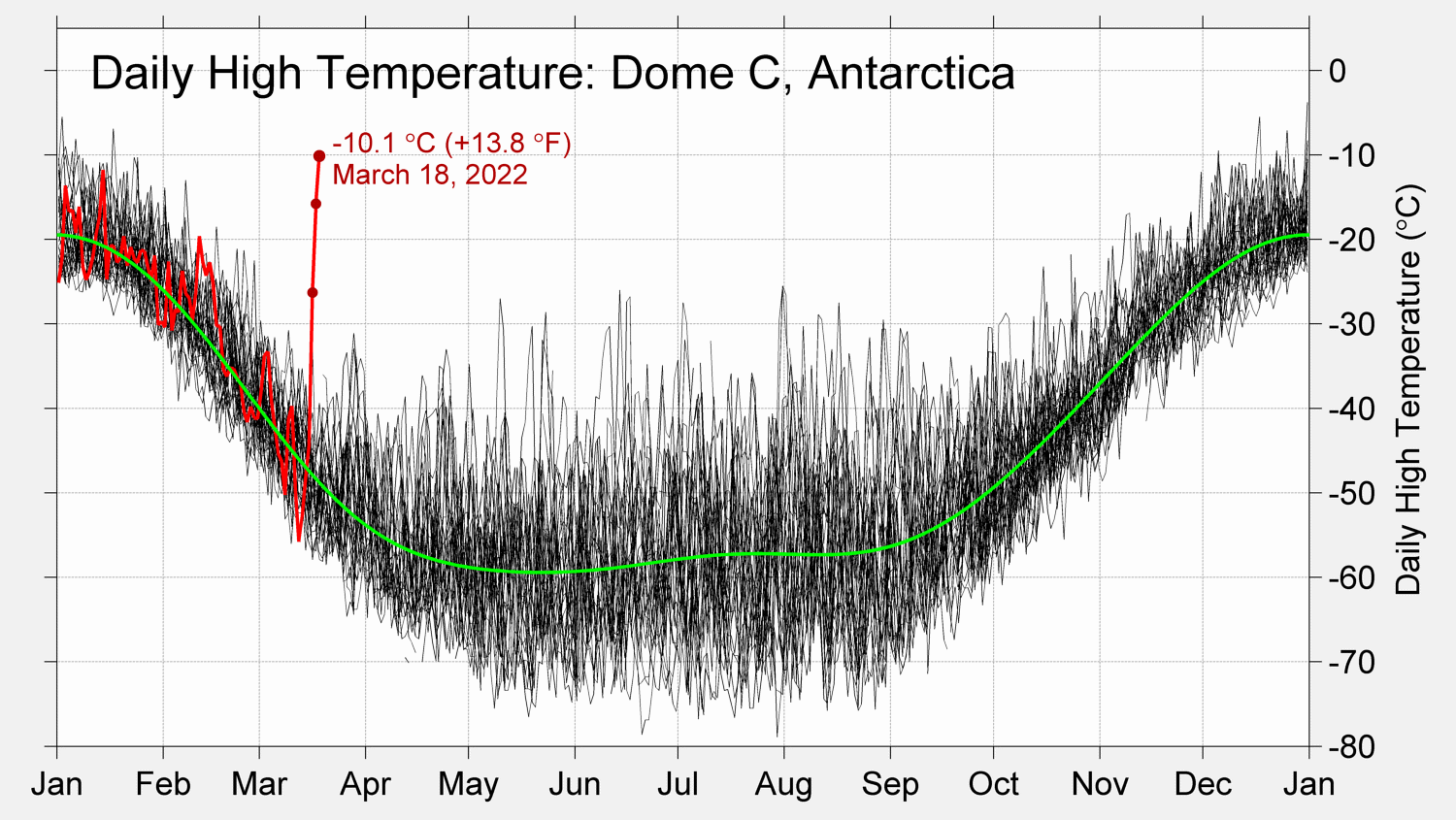

It’s 70 degrees warmer than normal in eastern Antarctica. Scientists are flabbergasted.

The coldest location on the planet has experienced an episode of warm weather this week unlike any ever observed, with temperatures over the eastern Antarctic ice sheet soaring 50 to 90 degrees above normal.

“This event is completely unprecedented and upended our expectations about the Antarctic climate system,” said Jonathan Wille, a researcher studying polar meteorology at Université Grenoble Alpes in France, in an email.

“Antarctic climatology has been rewritten,” tweeted Stefano Di Battista, a researcher who has published studies on Antarctic temperatures. He added that such temperature anomalies would have been considered “impossible” and “unthinkable” before they actually occurred.

Parts of eastern Antarctica have seen temperatures hover 70 degrees (40 Celsius) above normal for three days and counting, Wille said.

What is considered “warm” over the frozen, barren confines of eastern Antarctica is, of course, relative. Instead of temperatures being minus-50 or minus-60 degrees (minus-45 or minus-51 Celsius), they’ve been closer to zero or 10 degrees (minus-18 Celsius or minus-12 Celsius) — but that’s a massive heat wave by Antarctic standards.

The average high temperature in Vostok — at the center of the eastern ice sheet — is around minus-63 (minus-53 Celsius) in March. But on Friday, the temperature leaped to zero (minus-17.7 Celsius), the warmest it’s been there during March since record keeping began 65 years ago. It broke the previous monthly record by a staggering 27 degrees (15 Celsius).

“In about 65 record years in Vostok, between March and October, values above -30°C were never observed,” wrote Di Battista in an email.

Vostok, a Russian meteorological observatory, is about 808 miles from the South Pole and sits 11,444 feet above sea level. It’s famous for holding the lowest temperature ever observed on Earth: minus-128.6 degrees (minus-89.2 Celsius), set on July 21, 1983.

Temperatures running at least 50 degrees (32 Celsius) above normal have expanded over vast portions of eastern Antarctica from the Adélie Coast through much of the eastern ice sheet’s interior.

Extraordinary anomalies in #Antarctica lead to historic records today:

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) March 18, 2022

-Vostok 3489m -17.7C,monthly record beaten by nearly 15C !

-Concordia 3234m -12.2C,highest Temp. on records and about 40C above average !

-Dome C II 3250m -10.1C

-D-47 1560m -3.3C

-Terra Nova Base 74S +7.0C pic.twitter.com/w6Ry4Dy4wz

Eastern Antarctica’s Concordia research station, operated by France and Italy and about 350 miles from Vostok, climbed to 10 degrees (minus-12.2 Celsius), its highest temperature on record for any month of the year. Average high temperatures in March are around minus-56 (minus-48.7 Celsius).

At a nearby weather station, the temperature reached 13.6 degrees (minus-10.2 Celsius) about 67 degrees (37 Celsius) above average, according to University of Wisconsin Antarctic researchers Linda Keller and Matt Lazzara.

Keller and Lazzara said in an email that such a high temperature is particularly noteworthy since March marks the beginning of autumn in Antarctica, rather than January, when there is more sunlight. At this time of year, Antarctica is losing about 25 minutes of sunlight each day.

Wille said the warm conditions over Antarctica were spurred by an extreme atmospheric river, or a narrow corridor of water vapor in the sky, on its east coast. According to computer models, the atmospheric river made landfall on Tuesday between the Dumont d’Urville and Casey Stations and dropped an intense amount of rainfall, potentially causing a significant melt event in the area.

And just to leave this satellite image from today of the atmospheric river spreading clouds over East Antarctica pic.twitter.com/OdAy1Li6sS

— Dr. Jonathan Wille (@JonathanWille) March 17, 2022

The excessive moisture from the atmospheric river was able to retain large amounts of heat, while the liquid-rich clouds radiated the heat down to the surface — known as downward long-wave radiation.

Wille explained warm air is often transported over the Antarctic interior this way but not to this extent or intensity.

Models show the atmospheric river will exit the continent around Saturday, but the moisture will take longer to dissipate.

The abnormally high temperatures have caused some melting in the region according to models, which is unusual as this part of Antarctica doesn’t experience much melt often.

“This event happened in a location that doesn’t often have melt. Obviously, this doesn’t mean that from now on we’re worried that melting will happen,” Wille said.

Wille said it’s difficult to attribute this one event to climate change at the moment, but he does think rising temperatures helped prime conditions for such an event.

Wille and his colleagues are studying how climate change will affect the circulation patterns around Antarctica and whether atmospheric rivers will become more common or more intense.

“We do believe they will become more intense because it just simple physics … but the details, we’re still trying to figure that out. It would be very difficult to say that there’s not a climate change fingerprint on an event like this,” he said.

Keller and Lazzara suggested more study is needed on the climate change connection.

“[W]e can’t tell whether this is going to be a new trend or is just an oddity that occurs occasionally on a most fascinating continent,” they wrote.

Temperatures are known to vary wildly over Antarctica, and massive swings are common.

But shortly after that historic bout of cold, the sea ice extent surrounding the continent shrunk to its smallest extent just last month.

Amid all of the variability in Antarctica, fingerprints of human-caused climate change are still evident. Its western ice sheet is losing mass while western parts of the continent and the peninsula are among the fastest-warming regions on Earth.

Warm ocean temperatures threaten to destabilize Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, a slab the size of Florida that contributes about 4 percent of annual global sea level rise.

The historically high temperatures in Antarctica follow a pulse of exceptional warmth on the planet’s opposite end.

Links :