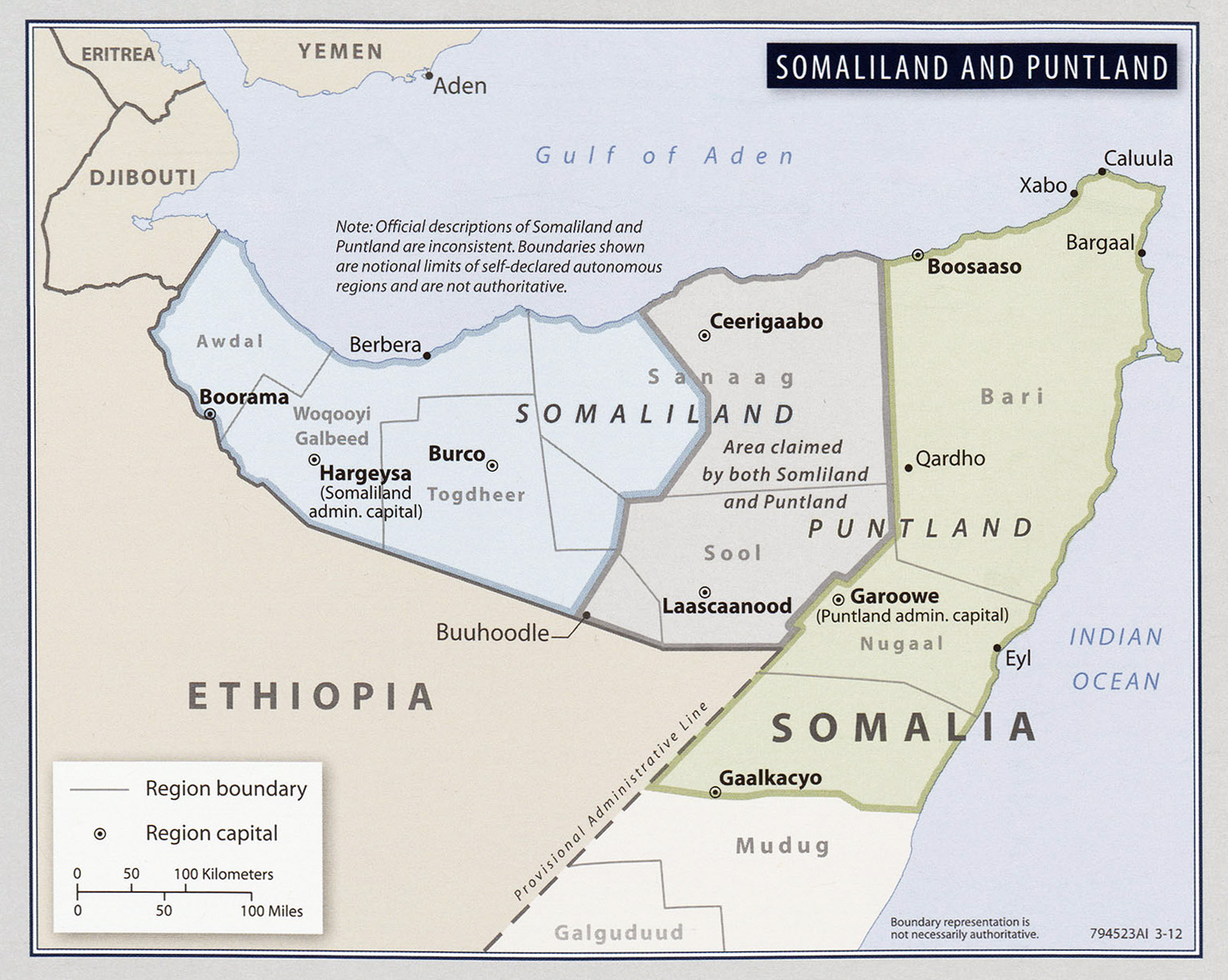

Illustration of the trajectory of all hurricanes since 1851, with emphasis on the trajectory of Hurricane Larry, on the large "garbage stain" of the North Atlantic, with high concentrations of microplastic. Image taken from Ryan et al (2023).

When Hurricane Larry made landfall two years ago, it dropped over 100,000 microplastics per square meter of land per day.

It’s another ominous sign of how plasticized the environment has become.As Hurricane Larry curved north in the Atlantic in 2021, sparing the eastern seaboard of the United States, a special instrument was waiting for it on the coast of Newfoundland.

Because

hurricanes feed on warm ocean water, scientists wondered whether such a storm could pick up

microplastics from the sea surface and deposit them when it made landfall.

Larry was literally a perfect storm: Because it hadn’t touched land before reaching the island, anything it dropped would have been scavenged from the water or air, as opposed to, say, a highly populated city, where you’d expect to find

lots of microplastics.

Anna Ryan collected samples of microplastics near Saint Michaels, N.L., a sparsely populated location with no major industry or other obvious sources of microplastics.

She says even the most pristine places now have plastics in the air.

(Submitted by Anna Ryan.)

As Larry passed over Newfoundland, the instrument gobbled up what fell from the sky.

That included rain, of course, but also gobs of microplastics, defined as bits smaller than 5 millimeters, or about the width of a pencil eraser.

At its peak, Larry was depositing over 100,000 microplastics per square meter of land per day, the researchers found in a recent

paper published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

Add hurricanes, then, to the growing list of ways that tiny plastic particles are not only infiltrating every corner of the environment, but readily moving between land, sea, and air.

As humanity churns out exponentially more plastic in general, so does the environment get contaminated with

exponentially more microplastics.

The predominant thinking used to be that microplastics would flush into the ocean and stay there:

Washing synthetic clothing like polyester, for instance, releases millions of microfibers per load of laundry, which then flow out to sea in wastewater.

But recent research has found that the seas are in fact

burping the particles into the atmosphere to blow back onto land, both when waves break and when bubbles rise to the surface, flinging microplastics into sea breezes.

Amber LeBlanc, a Dalhousie student who helped Ryan collect samples, checks a large glass cylinder set up near Saint Michaels, N.L., during Hurricane Larry.

(Submitted by Anna Ryan )

The instrument in a clearing on Newfoundland was quite simple: a glass cylinder, holding a little bit of ultrapure water, securely attached to the ground with wooden stakes.

Every six hours before, during, and after the hurricane, the researchers would come and empty out the water, which would have collected any particles falling—both with and without rain—on Newfoundland.

“It’s just a place that experiences a lot of extreme weather events,” says Earth scientist Anna Ryan of Dalhousie University, lead author of the paper.

“Also, it’s fairly remote, and it’s got a pretty low population density. So you don’t have a bunch of nearby sources of microplastics.”

A sample of the microplastics collected by Dalhousie students durring Hurricane Larry, as seen through a microscope.

(Submitted by Anna Ryan)

The team found that even before and after Larry, tens of thousands of microplastics fell per square meter of land per day.

But when the hurricane hit, that figure spiked up to 113,000.

“We found a lot of microplastics deposited during the peak of the hurricane,” says Ryan, “but also, overall deposition was relatively high compared to previous studies.” These studies were done during normal conditions, but in more remote locations, she says.

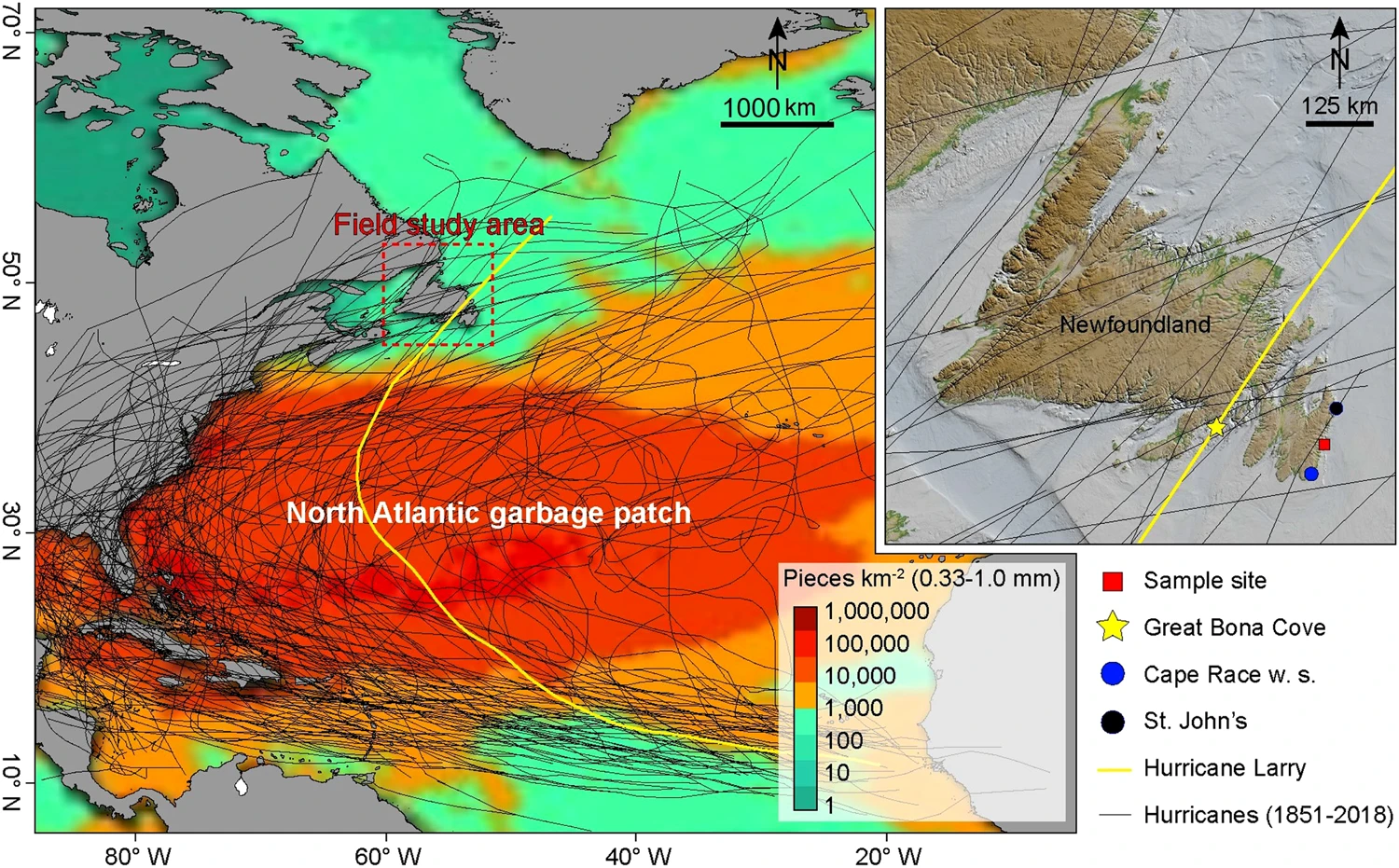

The researchers also used a technique known as back trajectory modeling—basically simulating where the air that arrived at the instrument had been previously.

That confirmed that Larry had picked up the microplastics at sea, lofted them into the air, and dumped them on Newfoundland.

Indeed,

previous research has estimated that somewhere between 12 and 21 million metric tons of microplastic swirl in just the top 200 meters of the Atlantic, and that was a significant underestimate because it didn’t count microfibers.

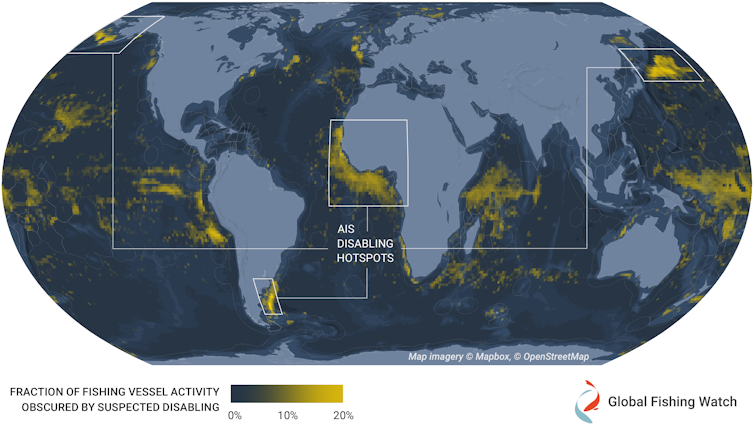

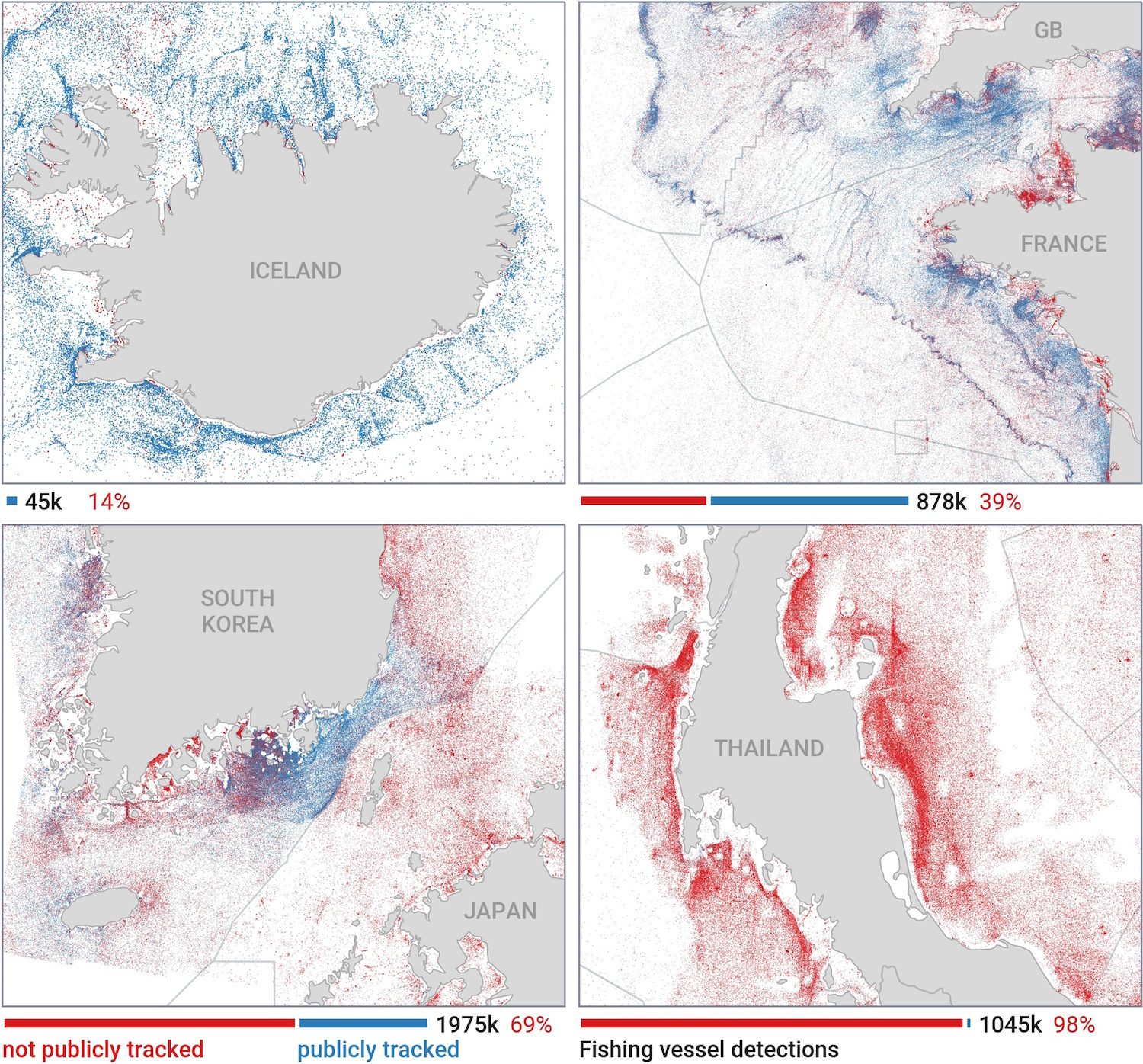

The Newfoundland study notes that Larry happened to pass over the garbage patch of the North Atlantic Gyre, where currents accumulate floating plastic.

These new figures from Newfoundland are also likely to be significant underestimates—and necessarily so.

It remains difficult and expensive to look for the smallest of plastic particles: This research searched for bits as small as 1.2 microns (1.2 millionths of a meter), but there were likely way, way more pieces of plastic smaller than that falling into the instrument.

“From previous studies, we know that there’s an exponential curve for particle numbers as you go smaller,” says University of Birmingham microplastic researcher Steve Allen, coauthor of the new paper.

“So we’ve been talking about 113,000 particles per square meter a day of big stuff.

It just must be staggering, what is smaller.”

The researchers could also determine what kinds of plastic had fallen out of the sky.

“We saw not an overwhelming amount of one certain polymer—there’s a real variety,” says Ryan.

“In the ocean, there’s such a mix of particles that you have a little bit of everything.

And also because the hurricane came from so far away: It formed off the west coast of Africa, and you could potentially have particles picked up from all the way back there.”

This echoes what other scientists have been finding with microplastics in the environment.

Microplastic pollution comes from so many sources—our clothing, car tires,

paint chips, broken-down bottles and bags—that it’s all mixed into a kind of multi-polymer soup out there.

That’s true both in the oceans and in the sky: In remote stretches of the American West, microplastic-sampling instruments similar to the one in Newfoundland have been gathering huge numbers of particles falling as

plastic rain.

Microplastics haven’t just gone airborne, but have become

a fundamental component of Earth’s atmosphere.

So microplastics don’t just flush into the sea and stay there—they blow into the atmosphere and back onto land, only to get picked back up again by winds and blown out to sea.

Back and forth, back and forth.

“It’s becoming quite clear that the ocean-to-atmosphere exchange is a very real thing,” says Allen.

“And the numbers in this paper here are just staggering.

It’s arriving in Newfoundland at just the time of year when all the biota—in the ponds and things—are all just trying to fatten up and breed for winter.”

Because microplastics travel so readily on winds and ocean currents, what were once considered pristine environments are now anything but.

Scientists are racing to figure out how the particles are affecting the organisms there.

Microplastics from Europe, for instance, have

polluted the Arctic, in turn

contaminating the algae Melosira arctica, which grows on the underside of sea ice.

The algae are the very base of the Arctic food chain, meaning all sorts of organisms are consuming them plus their accumulated microplastic.

As if hurricanes couldn’t get

any worse, they’re yet another way for plastic particles to spread where they don’t belong.

Activists gathered outside Norway’s parliament, protesting the country’s plans for deep-sea mining.

Activists gathered outside Norway’s parliament, protesting the country’s plans for deep-sea mining. Deep-sea coral off the East coast of the U.S.

Deep-sea coral off the East coast of the U.S.