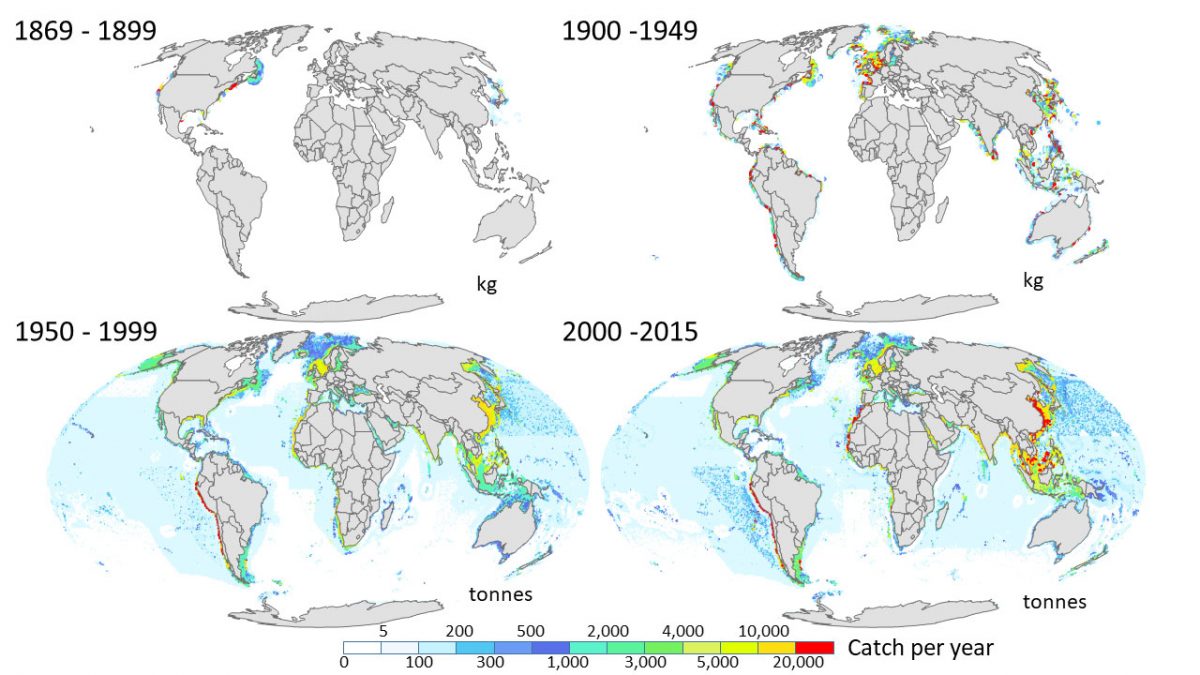

Prior to major advances in fisheries technologies, such as trawl nets,

steamships, and radar, annual catches of fish were measured in

kilograms.

Today, regional catches can number in the tens of thousands

of tonnes per year

picture : Mevagissey Luggers heading out to sea from an old post card

From Hakai Magazine by Gemma Conroy

A new data set shows how marine fishing has changed over time.

For thousands of years, seafood has sustained communities, livelihoods, and economies across the world.

In ancient Rome, wealthy entrepreneurs snapped up beachfront property and built elaborate fish farms.

In

15th-century Chile, coastal people bartered shellfish for inland resources.

The Vikings living on Norway’s Lofoten Islands were fierce and powerful raiders, but

they were also prodigious fishers of Atlantic cod.

Over millennia, shifts in politics and changing technology have drastically altered when and where people go to fish.

But accurate scientific records of this vast history of fishing activity capture, at best, a tiny sliver of the whole.

Most scientific studies of global fishing patterns only extend back to the 1950s, when groups such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization began keeping detailed records.

Today, these mid-century records are used as the baseline against which modern fisheries data is compared when making decisions about fisheries management and marine conservation.

But Reg Watson, a fisheries ecologist at the University of Tasmania, was unsatisfied with this truncated view of history.

Over the past 150 years, global fishing activity has been concentrated in hotspots.

Advances

in navigational, shipping, and storage technologies have enabled

fishing vessels to spread out around the globe, while changes in

politics and economics have shifted the locations of peak fishing

activity.

Illustration by Watson and Tidd

In a new research effort, Watson and his colleague Alex Tidd, a fisheries scientist at the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology in Ireland, scoured online databases, regional management records, vessel-tracking satellites, and historical records dating back to 1869 to produce

the first comprehensive maps of global marine fishing over the past 150 years.

The study doesn’t account for the full history of fishing, of course, but it does reveal detailed patterns of fishing across countries, including differences in catch composition and fishing gear, for a much bigger period of history than previous records.

Watson and Tidd’s reconstructed records also estimated the rates of illegal, unreported, and discarded catch.

Watson says examining fishing trends over such a long period offers a glimpse of how fishing has changed marine biodiversity.

Looking back in time gives researchers a clearer idea of historical fish populations before they were heavily exploited by modern industrial fishing.

This information can be used to assess the sustainability of modern fishing activity.

“It’s like playing a detective game,” says Watson.

“There’s a lot you can do with these maps, from figuring out greenhouse gas emissions produced by fleets to seeing how fishing impacts wildlife.”

Fisheries ecologist Chris Wilcox was not involved in the research effort but is already putting Watson’s findings to use.

Wilcox’s team at the Australian government’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation is using the data to investigate the link between fishing activity and seal entanglement.

By examining fishing levels in regions where there are seal colonies, the researchers will be able to gauge whether discarded fishing gear is the main cause of seal entanglement.

Many organizations, such as Global Fishing Watch, keep an eye on large-scale commercial fishing.

But Wilcox says Watson’s maps reconstruct the difficult aspects, such as how much smaller vessels caught or the amount of illegal catch.

“It has a lot of value for people who are trying to understand how fisheries are depleting ecosystems,” explains Wilcox.

Overfishing

Overfishing

The findings show that before 1900, the United States, Canada, and Japan had the most active fisheries.

Even still, landings were recorded in kilograms, not tonnes, and the majority of fish were bottom-dwellers and small pelagic species.

After the turn of the century, the United Kingdom caught up, with recorded landings peaking in the 1930s and 1940s.

Technological change spurred a new era of offshore fishing in the first half of the 20th century as sails and oars were replaced with diesel and steam, enabling vessels to travel farther and withstand stormy seas.

While the Second World War slowed fisheries expansion, the industry rebounded to full force during the 1950s economic boom.

The world’s first freezer trawler, the Fair Try,

was launched in 1953 and paved the way for more distant voyages and global trading.

Fleets began to trawl the seafloor and undertook long voyages to catch tuna, squid, and shrimp.

Some poorer countries reduced their own commercial fishing and allowed foreign fleets into their waters.

Japan, Peru, and Russia crept to the top of the list for global fisheries landings.

From Africa to South America, China’s fishing fleet outstrips the competition

Survey – said to be the most comprehensive of its kind – says China’s fishing fleet operated more hours in 2016 than the next 10 biggest nations combined

Today, China dominates.

The country ramped up its global fleet in the early 2000s,

its vessels roaming foreign waters more than its own.

Technological advancements, such as sonar and radar, have enabled fishing vessels to track sea conditions and work through the night.

While industrial fleets are traveling farther and fishing deeper than a century ago, the number of fish caught has actually been falling since the 1990s.

Watson says the reasons differ across the world.

In some areas, fishing has been curtailed in the interest of sustainable management.

In others, the sea has simply been overfished.

Far from home: Distance patterns of global fishing fleets

Global fisheries have evolved greatly over the past 150 years.

According to Watson, the next 150 could see important changes, too.

In particular, he sees a number of challenges.

Demand for seafood may rise even further as food systems on land falter under climate change, he says.

But if fuel becomes a more limited resource, fleets may not be able to travel as far offshore as they currently do.

This may result in an expansion of aquaculture, which could place even more pressure on coastlines.

“We’re beginning to see how everything is connected,” says Watson.

“It’s not just about looking at where catch comes from, but the bigger picture of fishing and our dependency on it.”

Links :

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/5TK2DULO3NA2XKIWMKRMCMQDKU.jpg)