Saturday, January 15, 2022

Lofoten

Friday, January 14, 2022

Shipping containers overboard

From Clear Seas Center

Why are shipping containers lost at sea and where do they end up?

There was a brisk wind blowing off Canada’s Pacific coast as the small boat approached the beach on its perilous mission.

Cold, salty sea-spray was blowing back, stinging the faces of the volunteers as they were trying to steady themselves along with their burlap bags and equipment, all while the boat was being tossed around in the choppy seas.

One misstep by either the skipper trying to steady the boat or the volunteers getting ready to jump into the water and clamber up the rocky beaches that dot the gnarly, rocky coastline could be catastrophic.

The waters funnelled into narrow channels making it even more difficult to navigate and land, as each cycle of waves ebbed and flowed.

For Lilly Woodbury, the regional manager of the Surfrider Foundation, an organization dedicated to cleaning up the oceans, the scale of the destruction ashore was immediate.

She was overwhelmed by the devastation and the sheer jumble of debris that was strewn in this once natural environment.

“It was the ghastly yellow polyurethane foam and Styrofoam, which ended up washing and blowing up literally like polyurethane bombs,” she said.

“It was very visible, very tangible.”

As she was picking up the waste her eyes caught a small creature wedged in between some foam – it was a tiny salamander and she realized just how distressing and upsetting the scene was.

“It really broke my heart to see all this foam on the beach, blowing into the forest, and little creatures like salamanders sandwiched between this ghastly toxic waste,” she said.

The plastic breaks down and floats, creating the likelihood that marine animals and fish will eat it.

Woodbury continued: “These little balls of yellow and white foam look like food, so it’s hard to track evidence of them eating it.

On the shoreline, you do find plastic foam bitten into by wolves and bears and other animals.

You see bitemarks, so you know they are trying to eat it.”

Woodbury and the other volunteers were now faced with a Herculean, almost impossible, task: to clean up the twisted metal and insulation from what was left of 35 empty shipping containers that had previously spilled from the Hanjin Seattle container ship and were relentlessly pounded by the unforgiving waves and tides of the Pacific Ocean.

Just a few months earlier Woodbury was at the other end of the Pacific when this barrage of wreckage fell into the ocean.

It was Nov. 3, 2016.

The container ship Hanjin Seattle was finishing a journey to drop off a number of full shipping containers – known as sea cans in maritime parlance – in Seattle, WA, and Vancouver, BC, and then home to South Korea.

The company was in the midst of bankruptcy and financial resources were scarce.

It should have been a routine voyage, but the Pacific Ocean is well known by mariners for its strong winds, rough seas and powerful storms.

Just west of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the vessel hit heavy seas and, in a few short minutes, its empty containers were lost overboard.

After reporting the incident, the ship continued its journey to Seattle to drop off some damaged containers and to have the remaining containers rearranged and secured for safe travel.

Upon hearing the news, the Canadian and US Coast Guard issued warnings to shipping that there were containers floating in the busy channel, some of which could have sunk, while others might still be floating just under the waterline.

Beyond those initial reports little was known about what happened to the containers and where their final resting place might be.

That situation was soon to change.

Reports started coming in that some of them were washing ashore intact while others were in fragments across 60 kilometres of the shores and archipelago that is Canada’s Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

Why do containers fall off ships?

The World Shipping Council (WSC) reported that an average 1,382 containers were lost at sea between 2018 and 2019.

The worst year occurred in 2013, when the MOL Comfort sank in the Indian Ocean with a loss of 4,293 containers.

Another spike happened between Nov.

2020 and April 2021, when it is estimated that nearly 3,000 containers were lost in the North Pacific in five separate incidents.

That’s double the annual average in a matter of weeks.

So, what’s going on?

There is a range of explanations of why containers fall off ships.

Prior to the losses of 2020/21 the WSC issued a report that reviewed the scope of the problem.

In the more recent losses, the WSC, International Chamber of Shipping and the Baltic and International Maritime Council told the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Maritime Safety Committee (MSC 103) that it believed no single factor caused the incidents but rather that there might have been several causes.

This included stormy weather, ship design, propulsion issues and how containers are lashed together including varying regulations around the latter.

The degradation of containers and resulting metal fatigue could also be considerations.

In some instances, containers may not be loaded correctly and inadequately secured for rough seas.

Container ships are also getting larger and stacked to the equivalent height of a medium-sized building.

There are also more of these ships at sea as global trade expands.

Climate change induced storms, especially in the North Pacific could be another culprit.

In an article in Insurance Journal, Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty notes that most of the recent incidents involving containers have occurred in the Pacific Ocean, a region with the busiest marine traffic and some of the heaviest weather in the world.

According to their analysis, there are a number of reasons for the losses, but climate change plays a role: “The journey has always been rough, but it’s become more perilous due to changing weather patterns.

The rise in traffic from China to the U.S.

this past winter coincided with the strongest winds over the Northern Pacific since 1948, increasing the likelihood of rougher seas and bigger waves, said Todd Crawford, chief meteorologist at The Weather Company.1”

But as these ships and their loads become larger and higher, their very stability is at risk.

A phenomenon called parametric rolling can happen when waves hit the front of the ship at an angle, rather than head-on.

As a result, the ship could go into a rolling motion synchronized with the waves which, combined with the ship’s normal pitching as it moves forward, can cause containers to break free from their lashings and tossed overboard.

Maritime officials say ship operators are looking at installing sensors that could issue warnings on sea conditions to avoid it.

“The higher you stack the boxes on deck, the larger the forces they are subjected to when the vessel moves in waves, and this could be a contributing factor, especially as the recent demand boom has meant filling all ships to the brim,” Lars Jensen, chief executive of Denmark-based Sea Intelligence Consulting, explained to the Wall Street Journal.

Anna Larsson, Communications Director for the World Shipping Council, says that every container overboard incident is thoroughly investigated to find and learn from the causes behind it.

The final reports of the incidents at the end of 2020/21 are still pending, but it is clear that extreme weather and winds are a common denominator in these incidents.

Pinning this series of incidents on a specific cause is difficult, Larsson says: “The International Panel on Climate Change now make a clear connection between climate change and recent extreme weather events.

However, which factor to attribute to climate change when it comes to these specific events, we do not know.”

Opinions on the severity of the problem vary.

In the view of Lars Jensen, he does not believe that there is a major increase in container losses at sea.

The World Shipping Council found a tiny fraction, about .0006%, of the total containers shipped on the world’s oceans each year were lost.

“However, the number of containers lost increased sharply in 2020/21 driven by a couple of major events.

But, statistically speaking, I find it hard to see that as a pattern, it could equally well be a fluke,” Jensen said in an emailed response to a question from Clear Seas.

With that jump in losses in 2020/21, the Baltic and International Maritime Council and World Shipping Council are working in conjunction with the IMO and taking a number of actions such as mandatory container inspections and a code of practice for loss reduction.

In May 2021, the IMO’s Marine Safety Committee agreed to establish a compulsory system to declare the loss of containers and set up means to easily identify the exact number of losses which will help in tracking and recovery.

Still, this will not come into effect for at least 2023.

In Canada, there are no specific programs to fund container wreckage removal under the Oceans Protections Plan or provincial programs.

And as the case of the Hanjin Seattle illustrated, the chain of command for recovery and who would pay is not clear.

Zim Kingston incident: Containers topple off ship during stormy weather

Attention was again focused on container shipping safety on Canada’s West Coast when more than a hundred containers fell overboard from the M/V Zim Kingston during rough seas in October 2021 at the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Some of the shipping containers were carrying hazardous materials and ignited, causing a ship-board fire that lasted for several days.

Many of the containers sank; most remain unaccounted for.

Four containers were known to wash ashore along the coast of northern Vancouver Island.

Debris included Styrofoam, refrigerators, consumer products and packaging materials.

Clean-up crews were contracted and dispatched by the company that manages the ship.

The Canadian Coast Guard actively monitored the situation and provided regular updates on the status of the ship and the lost containers.

#CCGLive: The owner of the #ZimKingston has hired a contractor to remove debris from the beach as well as recover the containers. As of this update, no other containers have been found on shore. pic.twitter.com/BaSO6fQsr6

— Canadian Coast Guard (@CoastGuardCAN) October 29, 2021

Who’s responsible for retrieving containers?

Despite the recent incident involving the Zim Kingston, container loss isn’t a common occurrence in Canada.

But, when it does happen, it is the shipping company’s responsibility and not the Canadian Coast Guard’s to recover lost containers.

In the case of the Hanjin Seattle, the federal government could have forced Hanjin to remove the debris right away, but didn’t because it was not believed that by that time pieces of the containers posed any immediate environmental or navigational hazards.2

Still, there are no international conventions specifically covering the loss of shipping containers.

If contents contain dangerous materials their loss must be reported.

But if there is nothing harmful in the container, there is no obligation to report its loss.

In a recent interview with Ship Technology, Antidia Citores, international spokesperson for Surfrider Foundation, a Non-Governmental Organization dedicated to ocean and coastal protection, which has studied the issue, noted that: “We’ve found that on some occasions, the team on the boat said they only realized containers had been lost at sea once they had reached the port and had to make the inventory.”

There are international treaties and regulations which, in the words of the IMO “may be relevant in the cases of claims related to containers.” The Nairobi International Convention of the Removal of Wrecks has provisions that cover “hazards created by any object lost at sea from a ship,” which makes shipowners liable for damages and provides for direct action and claims against insurers.

But until clearer policies and regulations are in place, as the Hanjin Seattle incident illustrates, it often becomes the responsibility of volunteers and non-governmental organizations in coastal and First Nations communities to do the heavy lifting of cleaning up the mess.

Recovering lost containers: Anatomy of a clean-up

Back on Canada’s West Coast, although the Hanjin Seattle’s empty containers were largely forgotten and written off as losses by the end of 2016, for the residents of western Vancouver Island they were becoming a very real, and a much bigger problem.

Cleaning up this wreckage was now of paramount concern and the responsibility of hundreds of volunteers, led by Surfrider, as well as members of the Ahousaht First Nation, and Parks Canada staff, in whose jurisdiction most of the broken pieces were resting.

Many other locals acted independently collecting waste as they found it.

By April 2017, the clean-up crews started working in full force at 17 different sites around the Park Reserve, which had been heavily hit by these containers.

“So, we made a remote shoreline clean-up plan where they would go in doing the heavy duty work of cutting up the containers, doing the helicopter work, doing that really industrialized expertise work with contractors,” Woodbury explains.

“We got to the most seriously hit sites but foam is so insidious.

It breaks down into these tiny one millimetre balls and there’s millions of pieces.

You can’t pick it up, it’s too hard.

The sheer volume that’s mixed in the soil and the sand is way too much.

You do your best to pick up the big pieces before it breaks down,” says Woodbury.

“It almost becomes a lost cause requiring some heavy industrial systems to take out the sand and filter it to get out.

We collected large pieces but there are still remnants out there.”

As time ticked by later, the problem got worse.

“The containers were further encased in the sand and rock along the beaches.

The foam had already broken up into smaller pieces.

It’s very distinct foam.

We’re still finding foam along the coast; we still find it in 2021.”

In addition to removing Hanjin Seattle’s container wreckage, it was an opportunity to clean up tons of other marine debris.

“It really exposed the scale of how much other plastic pollution there was.

We were collecting from the Hanjin Seattle but also collecting tons of consumer plastic and fishing and aquaculture debris.

So, we were getting data not just on the container ship, but also the composition of consumer and industrial plastic which elucidate the policies need to address the real issue.”

As time went by, the volume of wreckage and plastic continued to climb.

They filled one ton super sacks which measure five foot by 35 inches by 50 inches.

“They are the size of a person and we filled up hundreds of them,” she said.

That was over and above the containers themselves that needed to be cut up by professional salvage crews and hauled out by helicopter.

Woodbury and her volunteers collected between 20 to 30 tons in total.

“And keeping in mind most of that was foam and plastic which on its own doesn’t weigh a lot.”

The clean-up crews worked closely with First Nations as the wreckage and pollution was largely on Indigenous lands and waters.

“All of our clean-ups are in partnership with First Nations.

Before we start, the very first thing we do is work with the Nation, get approvals, and see how we can work together.

We contract with people from the Nation, so it provides employment and respects their laws in their territories.

Their Elders and Chiefs come and do openings and blessings.

We collaborate as much as possible.”

Woodbury says that she feels that the shipping industry is disconnected from the repercussions of lost containers and doesn’t see the end result.

“If they’d been here on the ground they would have seen how disastrous it was for the coastline and how much that hurt the people who live here.

Honestly, it’s a form of ‘waste’ colonialism for the Indigenous People, the First Nation.

Were they compensated for the disaster that happened on their land? No.

But that waste material was just shipped off on to their territory without a thought.”

The loss of shipping containers at sea is a concern for the marine shipping industry.

While the numbers that fall into the ocean and wash ashore are still relatively small, it is clear that in the case of Canada’s West Coast the impact of lost shipping containers – even empty ones – can be devastating to local coastal communities as well as marine and land animals.

Although the Hanjin Seattle lost empty containers, the MSC Zoe, which lost 342 containers full of household products on New Year’s Day 2019 off the coast of the Netherlands illustrates the environmental issues associated with the waste from full containers.

Another serious incident occurred when 54 tons of nurdles, the pre-production elements of plastic, were lost off the coast of South Africa in 2017.

New regulations, stronger enforcement and improved safety should prevent many of these incidents from happening.

But even then, the legacy of a few broken shipping containers can be destructive and costly, and the salvage bogged down by confusion within different jurisdictions as to who’s actually responsible for cleaning it up.

Containers 101: A short history of the sea can

There are roughly 226 million container boxes shipped annually with some 6,000 container ships at sea at any point in time as part of the global supply chain.

They ship approximately US$4 trillion of commercial goods annually and have completely revolutionized global trade.

The concept of the container was conceived of by Malcom McLean, a former North Carolina truck driver in 1937 while he waited most of the day to deliver cotton bales on his truck to a pier in New Jersey.

“Suddenly it occurred to me: Would it not be great if my trailer could simply be lifted up and placed on the ship without its contents being touched?”

He put his idea into action as he converted the World War II tanker Potrero Hills to a ship capable of carrying containers and rechristened her the Ideal X.

She made her maiden journey on April 26, 1956, sailing from Newark, NJ, to Houston, TX, carrying 58 metal containers and 15,000 tons of petroleum.

McLean moved into ship owning with his company Sea-Land.

Initially the containers were loaded on their chassis, but later the chassis was left behind, enabling containers to be stacked.

The first vessel to carry containers only was Sea-Land’s Gateway City which made her maiden voyage on Oct. 4, 1957.

Shipping containers are mostly made from steel and come in two principal sizes (20 or 40 foot lengths conforming to twenty foot equivalent units or TEUs) for ease of fitting on ships, trains and trucks for intermodal transportation.

There are 11 types of containers and dimensions can vary slightly.

While some are a basic box, others called reefers can be insulated and contain refrigeration units for the shipment of frozen foods, vegetables, pharmaceutical and medical products, and other perishable items.

Others can be adapted to fit tanks for the shipment of liquids.

Sea cans carry building supplies, fertilizers, smart phones, furniture, appliances, pots and pans, just about anything you use in your daily life.

They can also contain hazardous materials, chemicals, and a range of what could be toxic products if spilled or leaked into the ocean.

Containers aren’t necessarily watertight, but may float in the event they go overboard.

Few are recovered: most sink or wash ashore.

Nearly seven decades later, the reality is that container ships have become a vital link in global trade and are being built to carry more containers than ever.

The Ever Ace, which is the world’s largest container ship, has a 23,992 TEU capacity, and is one of the most technologically advanced ships in the world.

And it’s that increase in size that could be leading to more mishaps.

- Insurance Journal. (2021). Shipping Containers Plunge Overboard as Supply Race Raises Risks.

- The Globe and Mail. (2017). How a bankrupt shipper’s blunder turned into a bureaucratic nightmare for Ottawa

- GeoGarage blog : The secret life of a container lost at sea / Ship loses more than 500 containers in heavy seas / The next global tech disruption will happen where few expect it

- Maritime Executive : Video: ONE Boxship Diverts After Container Loss in the Atlantic

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Indonesia’s land and maritime border disputes with Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam

Photo: Handout

From SCMP by Resty Woro Yuniar

Foreign minister Retno Marsudi says Indonesia will increase efforts to accelerate the demarcation of both land and sea boundaries

Boundary disputes must be resolved using international law, she says, echoing a stance Jakarta has taken on the South China Sea

When Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi announced her ministry’s targets for this year, she said the country would intensify negotiations to resolve border disputes with nations including Malaysia and the Philippines.

Indonesia, an archipelago of more than 17,000 islands, has decades-long land and maritime boundary disagreements with its neighbours.

Retno, who also highlighted her ministry’s achievements from last year, said boundary disputes needed to be resolved using international law.

This is a stance Southeast Asia’s largest economy, and founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, has also taken towards the South China Sea dispute.

Image: SCMP

Indonesia views itself as a non-claimant state in the dispute that Beijing, Taipei and four Southeast Asian states have over the resource-rich waters.

However, an area between peninsula Malaysia to the west and the island of Borneo to the east that Indonesia claims as part of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) does fall within Beijing’s nine-dash line.

Fishing vessels from both China and Vietnam frequently visit the waters around Indonesia’s Natuna islands.

Retno said 17 rounds of negotiations were conducted with the Philippines, Malaysia, Palau, and Vietnam last year.

“It is interesting to note that the total number of negotiation rounds conducted in pandemic times has [more than] doubled from 2020, [when there were] only seven rounds,” she said.

“In 2022, efforts to accelerate land boundaries demarcation and maritime boundary delimitation will be intensified,” she added, referring to the marking or describing of boundary limits.

What are Indonesia’s border negotiation targets this year?

In 2022, Indonesia will focus on four maritime boundary issues it has with neighbouring countries, Retno said.

Firstly, regarding Malaysia, she said Indonesia hopes “treaties on the delimitation of territorial waters in the Sulawesi Sea and in the southernmost part of the Strait of Malacca can be signed.”

Image: SCMP

Indonesia also hopes to begin negotiations “for the delimitation of the continental shelf at the technical level and to follow up on the agreement to delimit the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones with two separate lines” with the Philippines, Retno said, and resume negotiations with Vietnam to reach an agreement on the EEZ boundary line in waters near the South China Sea.

It also aims to reach a partial agreement on EEZ establishment with Palau, she said.

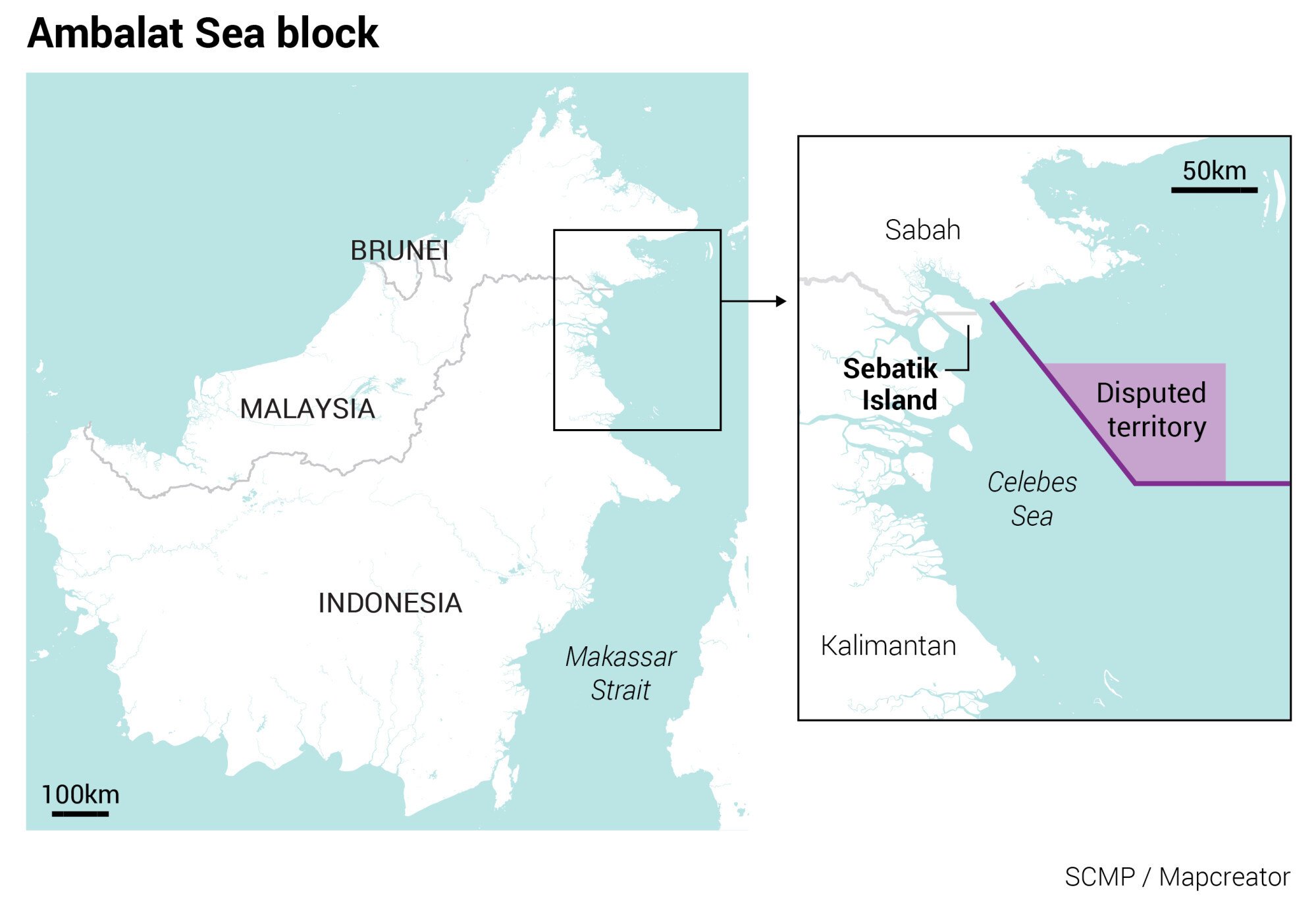

In relation to land boundaries, Jakarta also hopes to resolve demarcation issues related to outstanding boundary problems in the “eastern sector including Sebatik Island”, Retno said, referring to an outlying island off the eastern coast of Borneo.

The northern part of the island belongs to Malaysia and the southern part to Indonesia.

It also hopes to resolve disagreements over two sections of its border with East Timor, she said.

Indonesia controls West Timor, part of the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara, while East Timor – the east side of the island of Timor – is an independent nation.

What’s the Indonesia-Malaysia border dispute about?

In 1969, Indonesia and Malaysia agreed to a continental shelf boundary and a territorial sea boundary in the Malacca Strait and in the Natuna Sea portion of the South China Sea, on both the western side – off the coast of West Malaysia – and eastern side, off the coast of Sarawak.

But beyond that, the continental shelf and territorial sea boundaries in those waters have not been agreed on.

The 1969 treaty followed guidelines laid out by the 1958 Convention on The Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, which did not include guidelines on how to establish EEZs for coastal countries.

Indonesia ratified the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1985, which says a coastal country’s EEZ can extend up to 200 nautical miles offshore.

‘In the name of humanity’, Indonesia welcomes Rohingya refugees found adrift on broken boat

The agreement on the continental shelf and territorial sea boundaries that Indonesia and Malaysia signed in 1969 did not include details about Indonesia’s EEZ.

Malaysia views the treaty as the only one it has with Indonesia on maritime boundaries, as well as a tool that Indonesia can use to determine its EEZ.

According to Indonesia’s calculations, it is entitled to an extra 14,030 sq km of waters in the resource-rich area, if both countries agreed to the guidelines set out by UNCLOS.

“At stake are the abundant resources offered by these waters, but difference of perceptions between Indonesia and Malaysia have made it hard for them to discuss the maritime boundaries in the region,” said Fauzan, an international relations lecturer at Universitas Pembangunan Nasional in Yogyakarta focusing on border management and security.

Indonesia has underlined that it will strictly adhere to UNCLOS going into negotiations with Malaysia this year, with Retno saying Indonesia “will continue to reject any claims lacking an international legal basis”.

What about the Celebes Sea?

In this oil-rich region, Indonesia and Malaysia have no maritime boundary agreement.

In 1979, Malaysia unilaterally drew a map that depicted its territorial sea and continental shelf border, which included an area in the Celebes Sea, off the coast of Borneo.

Indonesia did not recognise this map and later said it owned the area of sea, calling it Ambalat.

Little did the two countries know that this dispute would blow up into one of their most thorny bilateral issues since Indonesia’s founding father Sukarno declared his anti-Malaysia stance in the early 1960s.

|

| Indonesia and Malaysia both claim an area, which Indonesia calls Ambalat, in the Celebes Sea. Their dispute over it has gone on for years. Image: SCMP |

In 2005, Indonesians took to the streets to protest Malaysia’s claims to Ambalat, after the latter’s state-owned oil and gas firm Petronas granted oil company Shell exploration rights in and around the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands, encroaching on the Ambalat area.

The dispute also led to a military stand-off, with Indonesia deploying four fighter jets to East Borneo after Malaysia sent patrol boats, warships, and air squadrons to the area.

The territorial dispute prompted Indonesia and Malaysia to deploy warships and fighter jets at the time.

Photo: AFP

In 2002, the International Court of Justice awarded the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands to Malaysia, but did not determine the maritime boundary in the surrounding waters.

The ownership of Ambalat, therefore, needs bilateral negotiations on the region’s maritime limits.

How about Indonesia and Malaysia’s land borders in Borneo?

The demarcation process so far has adhered to provisions in delimitation agreements agreed by British and Dutch colonial governments in 1891, 1915, and 1930.

Sebatik Island occupies around 452.2 square km and is located about 1km from mainland Borneo.

The northern part of the island belongs to Malaysia’s Sabah state, the southern part to Indonesia’s North Kalimantan province.

Indonesian Sebatik has 47,000 people, while Malaysian Sebatik has around 25,000.

A demarcated international border between the two countries has not been established in the eastern part of the island, including its maritime area.

The island reportedly has abundant – but untapped – oil deposits.

What about Indonesia’s demarcation efforts with the Philippines and Vietnam?

Indonesia and the Philippines have, since 2019, ratified EEZ boundary agreements that were initially signed in 2014, following a 10-year process.

The EEZ boundary is around 627 nautical miles long, taking in the Celebes Sea and the Philippine Sea, and is set out through eight geographic coordinate points.

In October last year, the Philippines and Indonesia held a preparatory meeting about the delimitation of the continental shelf boundary, in which both sides agreed to adhere to UNCLOS.

The two countries plan to hold an in-person meeting this year of their Joint Permanent Working Group on Maritime and Ocean Concerns on the Delimitation of Continental Shelf.

Indonesia agreed on a continental shelf boundary agreement with Vietnam in 2003, that produced a border around 250 nautical miles long.

However, both countries have yet to reach an agreement regarding EEZ delimitations in the South China Sea.

As a result, parts of Indonesia’s EEZ around the Natuna Islands is repeatedly encroached upon by Vietnamese fishermen, which sometimes leads to diplomatic protests by Jakarta and Hanoi.

These fishermen have been detained by Indonesian authorities in the past.

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Hottest ocean temperatures in history recorded last year

Air temperature at a height of two metres for 2021, shown relative to its 1991–2020 average. Source: ERA5. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service/ECMWF

From The Guardian by Oliver Milman

The world’s oceans have been set to simmer, and the heat is being cranked up.

Last year saw the hottest ocean temperatures in recorded history, the sixth consecutive year that this record has been broken, according to new research.

While the atmosphere’s temperature is also trending sharply upwards, individual years are less likely to be record-breakers compared with the warming of the oceans.

Last year saw a heat record for the top 2,000 meters of all oceans around the world, despite an ongoing La Niña event, a periodic climatic feature that cools waters in the Pacific.

The 2021 record tops a stretch of modern record-keeping that goes back to 1955.

The second hottest year for oceans was 2020, while the third hottest was 2019.

Source: Cheng, et al., “Another Record: Ocean Warming Continues through 2021 despite La Niña Conditions”, 2022.

Note: Average temperature of the top 2,000 meters of ocean water.

Zettajoules are a unit of energy equal to 10 to the power of 21 joules.

“The ocean heat content is relentlessly increasing, globally, and this is a primary indicator of human-induced climate change,” said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado and co-author of the research, published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

Warmer ocean waters are helping supercharge storms, hurricanes and extreme rainfall, the paper states, which is escalating the risks of severe flooding.

Heated ocean water expands and eats away at the vast Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, which are collectively shedding around 1tn tons of ice a year, with both of these processes fueling sea level rise.

This degrades coral reefs, home to a quarter of the world’s marine life and the provider of food for more than 500m people, and can prove harmful to individual species of fish.

As the world warms from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and other activities, the oceans have taken the brunt of the extra heat.

More than 90% of the heat generated over the past 50 years has been absorbed by the oceans, temporarily helping spare humanity, and other land-based species, from temperatures that would already be catastrophic.

The amount of heat soaked up by the oceans is enormous.

Last year, the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean, where most of the warming occurs, absorbed 14 more zettajoules (a unit of electrical energy equal to one sextillion joules) than it did in 2020.

This amount of extra energy is 145 times greater than the world’s entire electricity generation which, by comparison, is about half of a zettajoule.

Long-term ocean warming is strongest in the Atlantic and Southern oceans, the new research states, although the north Pacific has had a “dramatic” increase in heat since 1990 and the Mediterranean Sea posted a clear high temperature record last year.

The heating trend is so pronounced it’s clear to ascertain the fingerprint of human influence in just four years of records, according to John Abraham, another of the study’s co-authors.

“Ocean heat content is one of the best indicators of climate change,” added Abraham, an expert in thermal sciences at University of St Thomas.

“Until we reach net zero emissions, that heating will continue, and we’ll continue to break ocean heat content records, as we did this year,” said Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State University and another of the 23 researchers who worked on the paper.

“Better awareness and understanding of the oceans are a basis for the actions to combat climate change.”

- The Guardian : We study ocean temperatures. The Earth just broke a heat increase record

- CNN : Oceans were the warmest on record in 2021, for the 3rd year in a row

- Copenicus : Copernicus: Globally, the seven hottest years on record were the last seven; carbon dioxide and methane concentrations continue to rise

- NOAA : U.S. saw its 4th-warmest year on record, fueled by a record-warm December

- Springer : Another Record: Ocean Warming Continues through 2021 despite La Niña Conditions

- WP : Ocean warmth sets record high in 2021 due to greenhouse gas emission

- EcoWatch : Warmer Oceans May Lead to Smaller Fish, Study Finds

Tuesday, January 11, 2022

An 18-year-old woman is helping change the face — and speed — of sailing

The speed that hydrofoils add to boats transformed the world of competitive sailing, but it has nothing on the dizzying rate of CJ Perez’s ascent in the sport.

After starting to sail at 13, the Honolulu native turned 18 just in time to take her place aboard a state-of-the-art catamaran in October and compete in the world’s top sailing league.

Perez’s participation with the U.S. team at an event in Cadiz, Spain, made her the first American woman and the youngest person ever to race in SailGP.

18-year-old CJ Perez on racing aboard an F50 catamaran, importance of women competing

CJ Perez became the first American woman, first Latina and the youngest person ever to race in SailGP, the world's top sailing league. (The Washington Post)

Foiling refers to the use of watercraft with hydrofoils, winglike appendages that protrude from the bottoms of boats and boards.

“They are incredible and flat-out dangerous,” Nevin Sayre, who runs U.S. Sailing’s youth-oriented O’pen Skiff Class, said of the F50s.

Perez, however, is far from an average sailor. She began her career in 2016 on an O’pen Skiff (then called an O’pen Bic) and got so good so quickly that by March 2017 she finished fourth at the North American championships.

Perez then moved on to a 29er, another high-performance craft aimed at younger sailors, before starting to hone her foiling skills in 2020 on a WASZP, another one-person boat.

By then, Perez already had been selected for the SailGP team, and within days she was off to Cadiz for an F50 adventure that was, as she put it, “just the coolest thing ever.”

U.S. SailGP skipper Jimmy Spithill said that when he and other team officials first saw video of Perez foiling away in her WASZP, they were “not sure if she had done any racing at all or had been sort of sailing around on her own and learning it, [but] you could see that she had a lot of natural talent.”

“We just saw a huge amount of potential,” added Spithill, who led Oracle Team USA to America’s Cup victories in 2010 and 2013.

A native of Australia who resides in San Diego, Spithill has long been a prominent advocate for foiling, which dates back approximately a century in its earliest forms but didn’t make a major splash in competitive sailing until 2001, when a hydrofoil-equipped Moth boat won a world championship event in Australia.

The Ocean Race, sailing’s other traditional heavyweight crewed event, has since incorporated foiling, as have the Olympics.

“That’s the future,” Spithill said. “That’s what people want to do.”

His team’s emphasis on foiling skills over traditional sailing experience was underlined by the selection of 20-year-old Daniela Moroz, the five-time reigning women’s kitefoil world champion, who accompanied Perez in joining the SailGP squad in April after they were initially recruited as part of the Women’s Pathway Program.

“Daniela and CJ both bring to our team an impressive amount of foiling ability, which is paramount to racing at this level,” Spithill said then.

Moroz began learning how to sail a WASZP and develop some techniques that can translate to the F50, while Perez initially remained in Hawaii because of her youth.

“Kids four to five years older than her, none of them are going foiling at such an early age,” he said. “She’s at the cutting edge of a new generation, who are learning on both the O’pen Skiff and going right into foiling.”

Describing older sailboat models as “bathtubs with sails,” Sayre said they did not provide as appealing an entry into the sport.

“It’s like learning with a typewriter when these kids are used to iPhones,” he said.

Perez and Moroz also benefited from the Women’s Pathway Program, which Perez said was “really hopeful for the future of women in sailing.” Hannah Mills, a two-time Olympic gold medalist and three-time world champion who joined Britain’s SailGP team under the program, echoed Perez in hailing it as “a huge positive.”

“There is no hiding that right at the top of high-performance professional sailing it has been a male-dominated sport, but so have most sports,” Mills said via email.

Among the many unlikely aspects of Perez’s status in sailing is that before she took it up, she didn’t surf or engage in any of the aquatic sports readily available to Hawaiians.

“So I begged my parents to sign me up for spring break sailing camp,” Perez said, “and my passion for the sport really grew from there.”

Once she got into a skiff, Perez “fell in love with the ocean and all it has to offer,” and she has since taken up surfing and windsurfing, both with and without foils.

“These boats,” Spithill said of the F50s, “they’re aggressive, they’re fast and there’s risk there, so you need to have a roster with some depth.”

All that speed and danger, particularly as handled by eight boats stocked with top talent and packed into a tight course, are major selling points for SailGP, which announced recently that its third season will begin in May with teams from two additional nations to bring its total to 10.

What the U.S. team also does not have, according to the 42-year-old helmsman, is a regular supply of the kind of athletic sailors the new breed of foiling boats demand.

For Perez, who joined Spithill and other team members several weeks ago in a Foiling First camp in Chicago, the program is important because it could help “increase accessibility for communities less exposed to sailing.”

CJ Perez (foreground, second from left) helped show Chicago-area

junior sailors the ropes at a Foiling First camp in September

CJ Perez (foreground, second from left) helped show Chicago-area

junior sailors the ropes at a Foiling First camp in September“You didn’t see many people who came from communities of color; you didn’t see lots of females,” Perez said of the boat clubs where she began competing.

“Everyone should have the opportunity to experience this sport,” Perez added, “and have a shot at pursuing it to the highest level.”

In that light, Perez declared that foiling was not just an exciting version of sailing but “a rebirth.”

“We have this opportunity right now, with foiling,” she said.

Monday, January 10, 2022

Bordeaux - Tahiti : the transpacific crossing

Antarctica’s Doomsday glacier: how doomed are we?

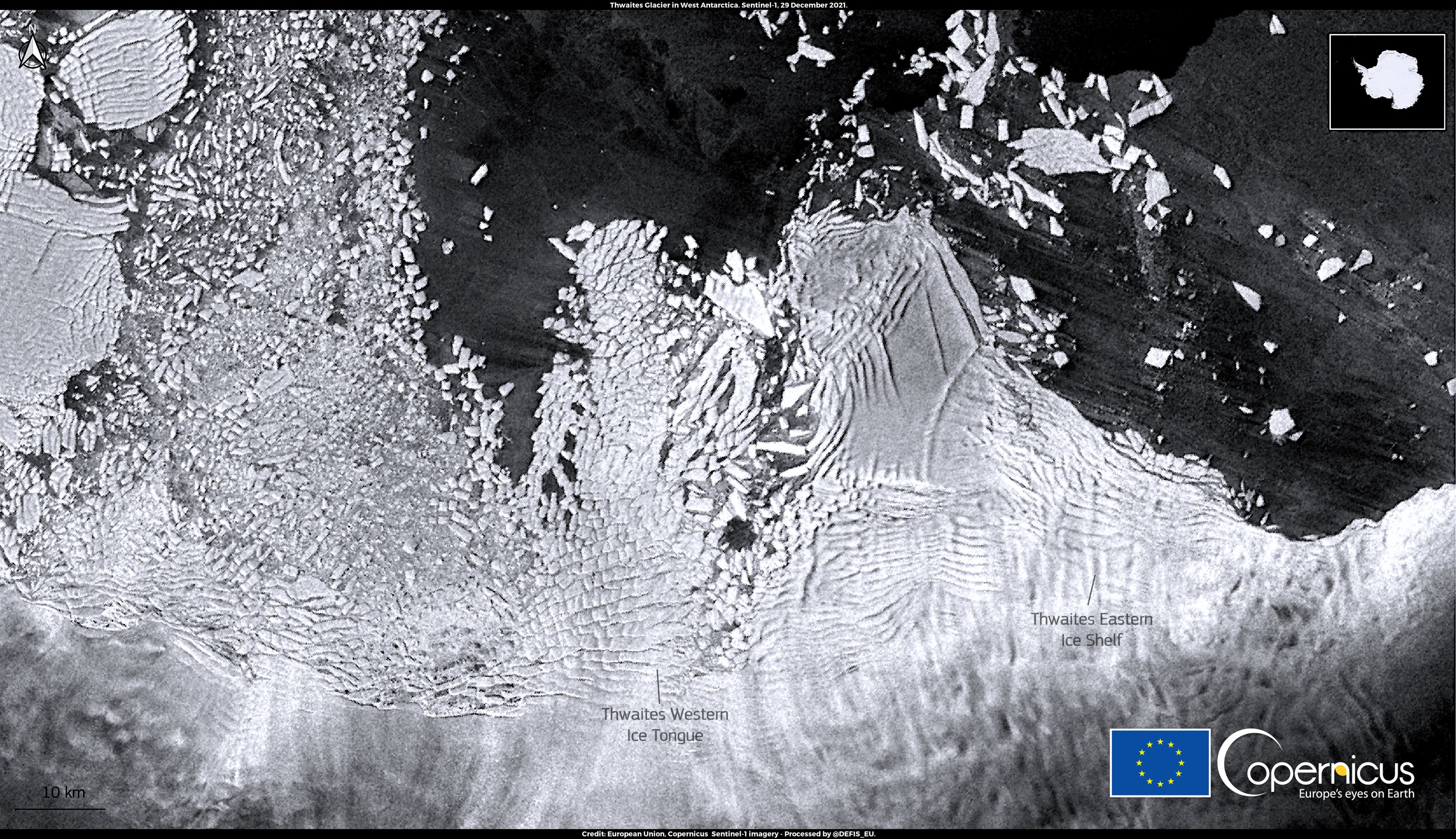

I came face to face with the Doomsday Glacier (a.k.a. Thwaites glacier) in 2019, on a trip to Antarctica aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer, a 308-foot-long icebreaker operated by the National Science Foundation.

I had dubbed the Florida-sized slab of ice its nickname in an article I’d written a few years earlier, and the name stuck.

Nevertheless, I was unprepared for how spooky it would be to actually confront the 100-foot-tall wall of ice from the deck of a ship.

Locked up here in the West Antarctic ice sheet was enough water to raise global sea levels nearly 10 feet.

As I wrote in a dispatch from Antarctica on the day we encountered Thwaites, it was both terrifying and thrilling to know that our future is written in this craggy, luminous continent of ice.

Our world is heating up fast.

And as every kid knows, on hot days, ice melts.

The question is how quickly.

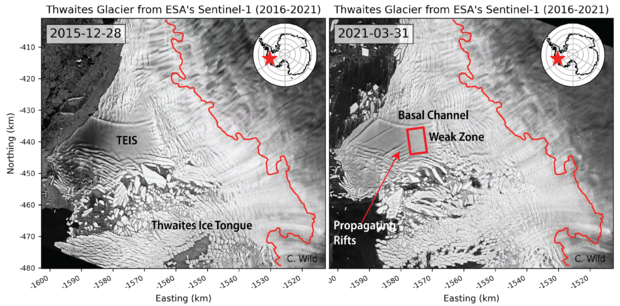

At Thwaites, the melting is mostly a result of warm ocean water attacking it from below, which is stressing and fracturing both the ice shelf that protects the glacier and the glacier itself.

Just how fast Thwaites and the other big glaciers that make up the West Antarctic ice sheet will all fall apart is one of the most important scientific questions of our time.

And it is a question upon which the future of virtually every coastal city in the world depends.

“We know there are tipping points in Antarctic ice sheets, and we also know that Antarctica is the biggest wildcard in the future sea level rise projections,” says Andrea Dutton, a professor of geology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a 2019 MacArthur Fellow.

“Basically, it all comes down to ‘when will we reach that tipping point?’ ”

Last week, two new papers were published simultaneously in the science journal Nature that offer radically different visions of the Doomsday glacier, as well as radically different visions of how climate models work and what they can tell us about the future.

But they agree on one thing: “Both papers make it very clear that human decisions are important, and that limiting warming can limit sea level rise,” says Richard Alley, a glaciologist at Penn State and one of the most respected ice scientists in the world.

But beyond that, the two papers may as well be describing life on different planets.

The first paper might be called the Holy Shit vision of Antarctica’s future.

In this scenario, led by Rob DeConto, a climate modeler at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst (Dutton and Alley and 10 other scientists are co-authors), the West Antarctic ice sheet remains fairly stable as long as warming stays below 2 C, which is the temperature threshold identified in the Paris climate agreement.

Beyond 2 C, however, all hell breaks loose.

Thwaites begins to fall into the sea like a line of dominoes pushed off a table and soon takes the rest of the West Antarctic ice sheet with it.

And once the collapse begins, it will be impossible to stop – at least on any human time scale.

In a century or so, global sea levels could rise 10 feet, which would swamp much of South Florida and Bangladesh and many other low-lying regions of the world.

In fact, it could happen even faster than that, says Alley: “We just don’t know what the upper boundary is for how fast this can happen.

We are dealing with an event that no human has ever witnessed before.

We have no analogue for this.” All in all, the paper makes a very strong argument that cutting emissions today may avert a centuries-long climate catastrophe.

DeConto’s paper also warns against betting on a quick techno-fix like CO2 removal.

Unless it is widely deployed by 2070, which, the way things are going, is highly unlikely given the cost and scale-up of the technology that is required, it will be too late.

The second paper might be called the What, Me Worry? vision of Antarctica’s future.

Unlike the DeConto study, which is based on a single model, the second paper, which was led by Tamsin Edwards, a climate scientist at King’s College London, involved 84 people working at 62 institutes in 15 countries.

Edwards and her co-authors use an “emulation” technique to compare the outcome of the different climate models, making the results less dependent on assumptions built into any one scenario, creating what amounts to a statistical average of climate-model outcomes.

In this study, the Doomsday glacier isn’t very doom-y at all.

There’s no collapse, no tipping point, no big jumps in sea level rise.

In fact, although the paper makes clear that the rate of CO2 emissions over the next few decades is clearly important, the difference in global sea level rise from the melting of all land glaciers, not just Thwaites, only differs by 4 ½ inches between a 1.5 C global temperature rise and a 3 C temperature rise (which is a little above where we are headed with current commitments under the Paris agreement).

And much of that comes from increased melt in Greenland and mountain glaciers.

As for Antarctica, the paper says explicitly: “No clear dependence on emissions scenario emerges for Antarctica.” Or as Alley put it to me, a tone of mild astonishment in his voice: “For Antarctica, the Edwards paper basically says, Antarctica doesn’t matter to us and our decisions don’t matter to Antarctica.”

So let me roughly sum up where we are with our scientific understanding of sea level rise risk from Antarctica after more than three decades of serious climate change research: One study tells us that if we don’t cut CO2 emissions fast we will condemn the world to a century of rising seas that will flood every major coastal city and reshape the global map.

The other study tells us that the likely difference between dramatically cutting CO2 emissions and cruising along on the current path is 4 ½ inches of water.

That means more coastal flooding, more erosion, more salt-water intrusion into drinking wells, but it’s a long way from Waterworld.

What to make of all this? Well, for one thing, the discrepancy between the papers demonstrates not only how little scientists really understand about what is going on in Antarctica, but also what a low priority our society has put on funding research to better understand it.

For another, modeling ice sheets is just plain hard, in part because it requires high-resolution models, and in part because a lot of the important events in the story of ice happened 20,000 years ago (or more), for which data is sparse.

Finally, there is a big difference in perspective between the two studies: The Edwards paper only looks at sea level rise out to 2100, whereas the DeConto paper stretches out to 2300.

Even in the DeConto paper, Antarctica doesn’t really start to fall apart until 2120 or so.

As always, what you see depends on the lens you look through.

There’s also the question of how additional snowfall from a warmer atmosphere may offset some or all of the melting from warmer ocean water.

(Warmer air holds more moisture, and thus can result in more snow.) As Edwards tells me via email, “We are not yet sure how much we have control over Antarctica, because snowfall has a counteracting effect that may also increase in future.”

The most important distinction, however, is that the DeConto paper includes a mechanism called Marine Ice Cliff Instability, or MICI (scientists pronounce it “Mickey,” like the mouse) and the Edwards paper doesn’t.

MICI is best understood as a hypothesis about how ice sheets behave in a rapidly warming world.

The gist of it is that, in some conditions, ice sheets don’t simply melt — they collapse.

Warm ocean water can get beneath the glaciers, causing them to fracture and destabilize.

When the ice shelves that keep the glaciers wedged in place break up, the glaciers themselves become vulnerable.

According to the MICI hypothesis, ice cliffs above about 100 meters high or so don’t have the structural integrity to stand on their own, and without ice shelves to buttress them, they will collapse, or calve, into the sea (there’s a more detailed explanation of MICI in my 2017 article on the Doomsday Glacier).

This is more or less what’s happening right now at a few glaciers in Greenland, including Jakobshaven, the fastest flowing glacier in the world.

A few years ago, I flew across the front of Jakobshaven in a helicopter and watched huge chunks of ice calve into the water, creating an army of icebergs that float out into Glacier Bay, where climate-catastrophe tourists take pictures of them and post them to their Instagram accounts.

The calving front at Thwaites is roughly 10 times bigger than Jakobshaven.

If Thwaites’ ice shelf breaks up and starts behaving like Jakobshaven, a whole lotta real estate is gonna get wet real fast.

MICI may be a radical idea, but it is not new.

It has been around since at least the 1960s, when climate scientist John Mercer first traveled to Antarctica and realized that the land beneath the ice in West Antarctica was shaped like a bowl, which means that if warm water got under the ice and began to destabilize the glacier, it could trigger a runaway retreat that could dump a lot of ice into the Southern Ocean very quickly.

Richard Alley took up the idea in the early 2000s, understanding it could be a mechanism to explain why sea levels were so high during the Pliocene era, 3 million years ago, when levels of CO2 in the atmosphere were about the same as they are today.

In 2016, DeConto co-authored a paper with Dave Pollard, a climate modeler at Penn State, that modeled the implications of MICI in Antarctica for the first time.

The paper added more than three feet to sea level rise projections and scared the bejesus out of climate scientists everywhere.

The MICI hypothesis also prompted the formation of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a five year-long, $50 million joint research effort between the U.S.

and the U.K., which began in 2018 (my trip to Thwaites in 2019 was with scientists participating in this joint research venture).

Among the key questions scientists are asking: How much warm water is getting under Thwaites ice shelf? (Quite a bit, according to a new paper by Swedish oceanographer Anna Wåhlin, which is based on measurements she made while we were in Antarctica together.) How quickly is the glacier losing its grip on the bedrock near the current ice front? How quickly is the ice shelf breaking up?

“In the last few years, we have seen a lot of dynamic change at Thwaites and other glaciers in the region,” says Robert Larter, a geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey who was the chief scientist on the Palmer on my trip to Antarctica.

According to one recent study, the net ice-mass loss from Thwaites and nearby glaciers is now more than six times what it was 30 years ago, which Larter calls “mind-boggling.”

None of this research is conclusive, and most of it is still too new in include in climate models.

For the moment, MICI remains an outlier idea, one that mainstream climate modelers have yet to fully embrace, despite the risks that civilization faces from it.

“If you want to be generous,” Alley tells me, “You could say that climate modelers really want to make their models carefully, make sure they are calibrated precisely, and they don’t know what to do with MICI.”

“The reason nobody is rushing off an unstable marine cliff in search of what DeConto and Pollard have done is because nobody thinks there is any good reason to single out MICI and make it the cause of instability in glaciers,” says Gavin Schmidt, a climate modeler and director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

“Is MICI a large part of why glaciers calve? It’s not inconceivable, but it’s also not inconceivable that it could be other factors.”

Finally, some of the resistance to MICI may simply be a failure of imagination.

No human has ever witnessed the rapid collapse of a glacier in Antarctica like Thwaites; ergo, it can’t happen.

Alley himself thinks about it simply in terms of risk.

“Maybe we’ll get lucky and the ice cliffs won’t disintegrate in Antarctica quite as fast as we predict,” he says.

“But if you are even a little bit worried that scientists might have made mistakes in their calculations about what is going on in Antarctica, then maybe we should pay attention to this.”

He compares Thwaites and other glaciers in West Antarctica with drunk drivers.

“They are out there, they are scary, and they don’t behave as you expect them to,” Alley says.

“That’s why it’s a good idea to have a seatbelt in your cars.”

In the end, climate modelers are a little like sci-fi writers.

They use facts and physics to spin out possible futures.

DeConto’s paper imagines we are moving into a new world that will behave very differently from the world we have lived in so far.

Edwards’ paper imagines that the rest of the 21st century will look pretty much like it does today, only hotter, and with a little less ice.

Both visions are based in science.

Both visions are plausible.

And both visions are fraught with deep uncertainty about where we are going.

I hope we live in Edwards’ world, but I fear we live in DeConto’s.

- Meteorological Tech Int. : Underwater robots to examine Thwaites Glacier’s impact on sea level rise

- Wired : How Explosives, a Robot, and a Sled Expose a Doomsday Glacier

- Gizmodo : Boaty McBoatface Prepares to Dive Under Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

- Rolling Stone : ‘The Fuse Has Been Blown,’ and the Doomsday Glacier Is Coming for Us All

- The Conversation : Antarctica’s ‘doomsday’ glacier: how its collapse could trigger global floods and swallow island

- GeoGarage blog : Thwaites: 'Doomsday Glacier' vulnerability seen in new maps / Unprecedented data confirms that Antarctica’s most dangerous glacier is melting from below