The teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg sails past the Statue of Liberty on the Malizia II racing yacht in New York Harbor as she nears the completion of her trans-Atlantic crossing.

An exploration of the value of ocean crossings in small vessels in pondering the climate change challenge.

An exploration of the value of ocean crossings in small vessels in pondering the climate change challenge.

Credit Mike Segar/Reuters

From NYTimes by Andrew C. Revkin

A trans-Atlantic crossing by boat can teach us about confronting the global warming crisis.

Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist, represents many things to many factions in the fight to slow human-driven global warming.

Some see her as a manipulated totem.

Others, as a hero.

I’m among those who see great value in Thunberg’s sharp prod to the status quo, though I see the greatest value in climate strikes pressing for global action if they are coupled with local efforts for clean-energy progress.

(Why not, for instance, call attention to the mostly-fossil-fueled boiler rooms heating and cooling schools, homes and workplaces.)

But this week, perhaps it’s worth focusing on some lessons that might be learned from her choice of transportation.

Ms. Thunberg and her father arrived in Manhattan on Wednesday after a 15-day crossing of the Atlantic from Britain as passengers on a spartan, high-tech multi-million-dollar ocean-racing yacht.

She’s here to help lead climate strikes on Sept. 20 and 27 demanding an end to the use of fossil fuels and speak in between at the United Nations Climate Action Summit and other events.

Her decision to make the trip under sail has been both hailed for highlighting low-emissions lifestyle choices and derided as showmanship.

Indeed, the aviation emissions of an army of journalists flying to cover her arrival and the summit eclipsed any savings her crossing achieved.

But there are other lessons that can be learned in an ocean crossing like hers.

I’m sure Ms. Thunberg will be changed by the experience.

I wish everyone could watch terra firma disappear as they cross a big ocean in a small boat.

The earth, after all, is itself a very small boat in the boundless ocean of space.

In 1978, when I was 22, six years older than Greta is now, I serendipitously had the chance to sign on as a crew member on a 55-foot-long, partially home-built sailboat, the Wanderlust, that was circumnavigating the planet.

I was in the South Pacific, having won a modest post-college traveling fellowship to visit small islands and study, yes, “man’s relationship to the sea.”

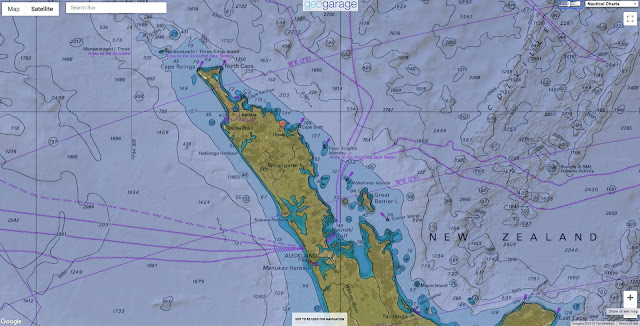

A “crew wanted” sign on a wharf along the harbor in Auckland, New Zealand, led me to the vessel, which hailed from Sacramento and consisted of an unusual ferrocement hull (cement smeared on a steel frame) and an equally odd assortment of fittings.

The mast was a surplus highway light pole.

The author on board the Wanderlust in the Red Sea in 1980.

I left the boat 17 months, 15,000 miles, 15 countries and several close calls later, in what was then Yugoslavia.

The intervening experiences shifted my career ambition from marine biology to environmental journalism.

Here’s a bit of what I learned, lessons that seem applicable to efforts to build wider momentum behind cutting greenhouse gas emissions and reducing climate risks.

Tight quarters require compromise.

Our first long crossing, from Auckland to Sydney, Australia, was the stormiest.

We spent eight out of 11 days on the Tasman Sea pounding into chaotic gale-driven seas.

Without GPS or an autopilot, we had taken on extra crew members to handle the night watches.

In cramped conditions day after day, everyone aboard felt unfairly overtaxed.

But you learn to smooth rough edges, tamp hard feelings and not hoard the Hershey bars.

Despite a no-smoking rule, the skipper, Lon Bubeck, even allowed the two chain smoking New Zealanders to light up — in the inflatable dinghy trailing behind.

This gets to my first point.

In hashing out climate policy, accommodation is vital among those who have the same goal but differ on how to reach it.

I’m thinking here, for instance, of clean energy advocates who disagree about the role of nuclear power in reducing emissions.

It’s vital to acknowledge the inevitability, even desirability, of having a diversity of climate solutions.

Panic doesn’t help.

When a rogue wave blew in a porthole crossing the Tasman, a piston-like column of green water blasted in every few seconds.

A similar porthole incident happened more than a year later in the Red Sea.

Each time, the skipper, who had spent years as a handyman in Santa Cruz, Calif., had an astonishing ability to assess the situation, identify a fix and hand out orders.

When his calm demeanor caught my attention, I stopped flailing around and focused on my task.

Which gets to my second point.

Many pressing for a Green New Deal of any sort have tried changing the global warming hashtag from #climatechange to #climateemergency.

Whatever you call this moment, it took more than a century for the world to become dependent on fossil fuels and, as the Paris Agreement on climate change recognized and Axios just reported, it will take decades to move the global economy to clean energy and cut or collect tens of billions of tons of annual emissions of carbon dioxide.

Urgency has to be blended with patience.

Vastness has limits.

I still meet people who insist that the human influence on the vastness of the atmosphere and oceans is inconsequential.

At sea, I experienced the full sense of the size and depth of the oceans when we were becalmed for several days halfway across the western Indian Ocean.

To cool off, wash and pass the time we went swimming — in water 14,300 feet deep.

I still get a cold chill when I recall looking down through my face mask at the vanishing points of my shadow and the Wanderlust’s bobbing a few hundred feet away.

But vastness has limits.

Long before today’s “planet or plastic” campaigns, we encountered jarring evidence of the activities of man even on isolated island beaches that rarely saw a footprint.

Anchoring off a remote beach on Mount Adolphus Island in the Torres Strait between Australia’s Cape York and Papua New Guinea, we collected a dizzying array of plastic flotsam — mostly lost or tossed fishing gear.

In 1980, transiting the Red Sea, we sheltered from gale winds in the lee of an uninhabited island off the coast of Yemen.

I hiked to the windblown southern shore and stumbled into tide-tossed heaps of light bulbs of all sorts.

With the atmosphere, humans could be perceived as a minuscule influence, having raised levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide from only 280 to 410 parts per million since the Industrial Revolution.

But that increase has had an outsize influence on the global thermostat.

It’s been three million years since the planet last hit that concentration and we’re on the path toward doubling preindustrial carbon dioxide within decades.

Vastness can deceive.

You can’t run away.

On a fateful night heading through the Gulf of Patras in Greece toward the Adriatic, I was alone at the wheel, with everyone else asleep below, as a violent gale built behind us.

I was unsure whether to keep the lighted buoy ahead to port or starboard.

I guessed wrong and we ended up aground on a sandbar, pounded by ferocious waves.

The Wanderlust being repaired in Patras, Greece, in 1980.

Credit Andrew Revkin

We were towed to safety, spent a month repairing the cracked cement hull, nervously relaunched and sailed on.

The cracks did not re-form.

But I was slowly realizing that I needed to get home to build a career.

Decades later, those powerful memories and lessons from life at sea still shape my life and how I view the path ahead.

Greta Thunberg’s journey so far has had a rocket-like trajectory.

Her voice and those of other young climate activists deserve amplification.

They represent generations who will inherit the climate we’re shaping today.

But the task of building a sustainable relationship with the climate requires all of us to push off from comfortable shores, respect (if not embrace) the diversity of views of fellow passengers, share our vessel’s finite resources and — most important — avoid panic and get down to work.

Links :

- The Conversation : Greta Thunberg made it to New York emissions-free – but the ocean doesn’t yet hold the key to low-carbon travel

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/KWBWAVGQQBH3VLHVPM7CR5MN3M.jpg)