"A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at,

for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing."

(Oscar Wilde)

From Gregory C. McIntosh book

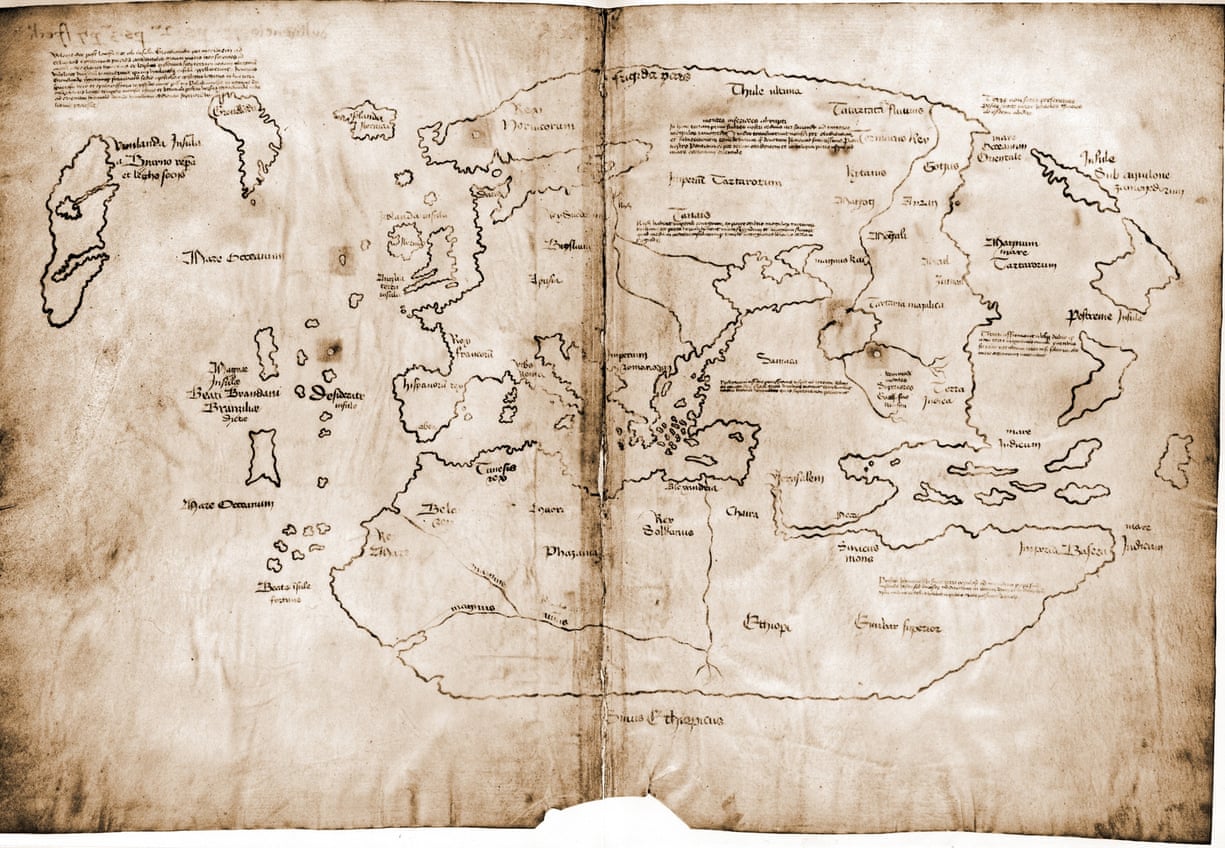

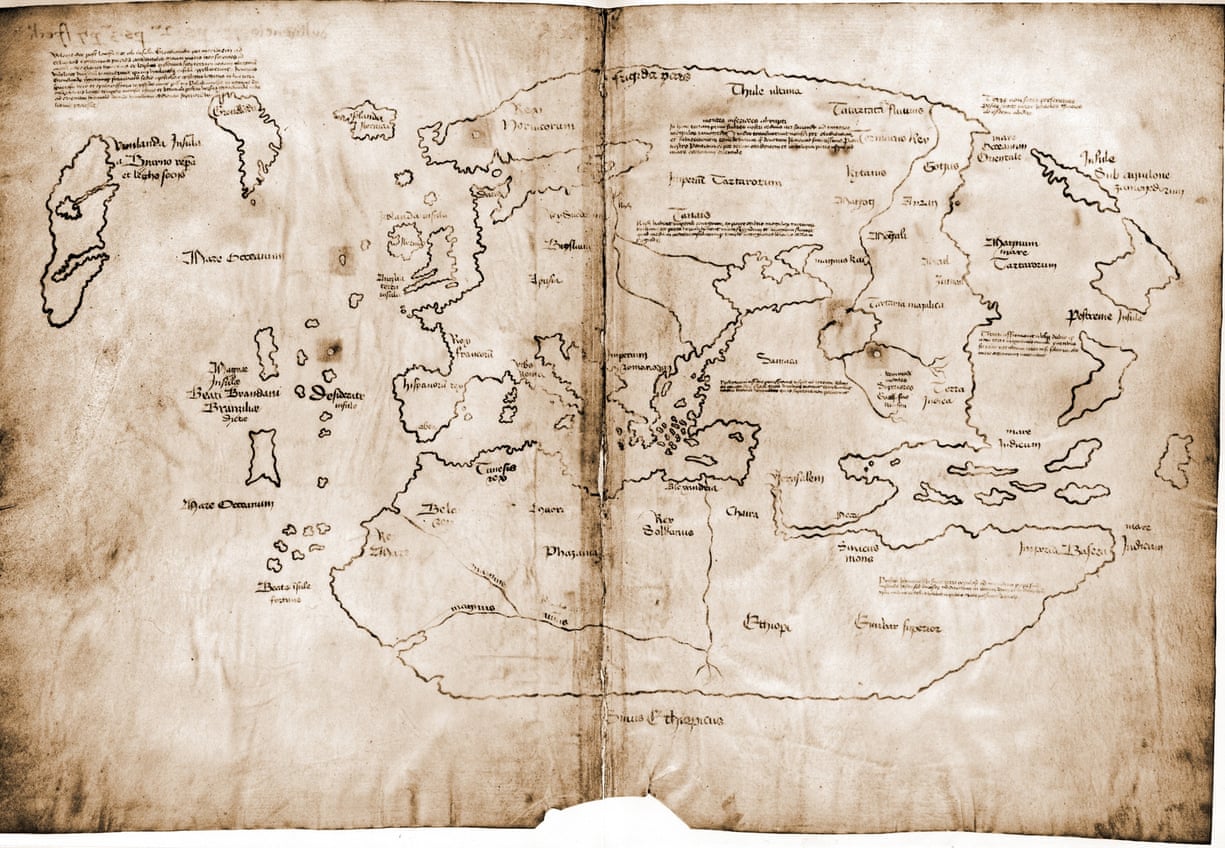

The Piri Reis map of 1513, the surviving left-hand portion of a larger world map, is one of the most beautiful, interesting, important, and mysterious maps to have survived from the Age of Discovery.

Yet for all its importance, it is one of the least understood maps of this momentous and remarkable period in the history of cartography.

It is fortunate that the surviving portion is of the newly discovered regions in the Western Hemisphere, not only because it contains a copy of a map of Christopher Columbus, but also because it documents some of the era’s evolving geographical conceptions of the New World.

The Piri Resi map is unusual for the number of inscriptions on the map giving information about people and animals of the New World, the voyages of Europeans, and the sources used by Piri Reis for his depiction.

An analysis of the map reveals some of the likely sources used by Piri and how he went about reconciling and blending together these several source maps into a world map.

From the map inscriptions we learn that Piri used a map by Christopher Columbus for his depiction of the West Indies.

An examination of the map confirms this fact.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the map is its connection to Christopher Columbus.

The Piri Reis Map exhibits many features in common with other surviving portolan charts and portolan-style maps of the fifteenth and Sixteenth centuries and fits well into the evolution of mapmaking from the late Middle Ages to the early Renaissance.

Many features of the map show close affinities to contemporary Portuguese maps confirming Piri’s own statements that he used Portuguese maps as sources for making his world map.

The Piri Reis Map displays the earliest, most primitive, and most rudimentary cartography of these islands, a primitiveness that indicates that the earliest of all cartographic records of the discoveries in the New World — a map made by Columbus, or made under his supervision, around 1495 or 1496 — is preserved in the Piri Reis Map.

The Piri Reis Map of 1513 is one of the most beautiful, interesting, important, and mysterious maps to have survived from the Age of Discovery.

Yet for all its importance, it is one of the least understood maps of this momentous and remarkable period in the history of cartography.

The map is the surviving left-hand portion of a larger world map.

The top edge displays evidence of another section of parchment above, which would have depicted Great Britain, Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland.

The extant fragment measures about 89 centimeters high by 64 centimeters wide.

The central section and right–hand (or eastern) portion of the world map are missing.

Piri tells us in his map inscriptions that among the maps he used to construct his world map there were Portuguese maps.

Several contemporary Portuguese maps have been used to reconstruct a suggestion of what the whole Piri Reis map looked like.

The complete world map probably measured about 140 centimeters high by 165 centimeters wide. It is fortunate that the surviving portion is of the newly discovered regions in the Western Hemisphere, not only because it contains a copy of a map by Christopher Columbus, but also because it documents some of the era’s evolving geographical conceptions of America.

The map follows in the tradition of portolan charts, mariners’s sea charts of the Black, Aegean, and Mediterranean Seas and the Atlantic coasts of Europe.

In response to European geographical expansion, portolan – style maps were expanded beyond the traditional European regions to include depictions of the entire world.

The graphical symbols, colors, and illustrations of Piri’s map are typical of portolan – style charts.

Like other portolan charts of the time, the Piri Reis map exhibits a network of rhumb lines radiating from a circular pattern of wind roses or compass roses, five of which can be seen on the extant fragment.

The central rose was in northeast Africa, a common motif.

The map includes 117 place – names.

Most are typical of portolan charts and easily identifiable, particularly those found in Europe, Africa, South America, and the Atlantic Islands (both real and imaginary).

The map also includes thirty descriptive inscriptions.

All but one is in the Ottoman – Turkish language.

The exception is in Arabic and identifies the mapmaker as Piri Reis and dates the map to the spring of 1513.

Other inscriptions give information about the people, animals, mineral wealth, and curiosities of the New World.

One of the inscriptions identifies the sources used by Piri Reis: eight maps of Ptolemy, four contemporary Portuguese maps, an Arabic map of Southern Asia, and a map by Columbus for parts of the New World.

The depiction of the New World, based upon a Columbus Map, and the depiction of land at the south of the Atlantic Ocean, have elicited the most interest.

Piri’s map appears to include in his depiction of a southern land the commonly held belief in a southern continent, accepted by geographers since the time of the ancient Greeks.

A southern continent had to exist in order to balance the globe with the other landmasses in the Northern Hemisphere Piri’s inscriptions on his southern land indicate that his compilation included reports from Portuguese voyaging along the east coast of South America.

The Piri Reis map is typical of most other world maps of the Sixteenth Century, which depict a southern continent with inscriptions describing South America.

The depiction of South America is rather typical for its time as seen in the delineation of the east coast, the northeast coast, and the mouth of the Amazon. The place-names along the east coast of South America are typical of all maps since the Portuguese first explored the coast after its discovery in 1500.

The place-names along the east coast of South America are typical of all maps since the Portuguese first explored the coast after its discovery in 1500.

Now, we do not have any difficulty seeing the outline of Europe, Africa, and the coast of South America on this surviving portion of the map.

But, what is this jumbled bunch of lands and islands up here in the northwest corner?

Let’s see if we can sort this out and figure out what was being represented here.

The islands of Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles are fairly easily discernible on the Piri Reis Map when we compare the delineation with other contemporary maps.

The name inscribed on Puerto Rico – Sanjuwano bastido – is San Juan Bautista, the name Columbus bestowed upon the island when he discovered it during his Second Voyage.

Stretching eastward from the northeast corner of Puerto Rico on the Piri Reis Map is a string of small, unnamed islands that are identified from their shape, size, location, configuration, and orientation as the present-day Virgin Islands.

There is also, however, a cluster of twelve islands located immediately to the northeast of the unnamed Virgin Islands, which, according to the inscription next to them, are called Undiziverjine, which is Italian for "Eleven Virgins,” derived, no doubt, from Columbus’s name for these islands, which was “Eleven – Thousand Virgins.”

The duplication of the Virgin Islands, once in their correct form and location, but unnamed, and again immediately to their northeast as a conventionally drawn cluster of islands, provides an important clue as to how Piri Reis extracted and reconciled the information from the two – dozen source maps he used.

We will look at this compilation process a little later.

The Lesser Antilles on the Piri Reis map are easily identified by the shapes, orientations, and place names of the islands. Some of these island place names preserve native Carib island names recorded in early Sixteenth Century documents.

According to Piri Reis, he used a map by Columbus for part of the depiction of the western regions or the New World.

An analysis of the depiction of Hispaniola, the Bahamas, and Cuba indicates that this is probably correct.

The depiction of Hispaniola on the map does not at first glance appear to resemble the true shape of Hispaniola.

It can be identified, however, by the place names inscribed upon it: Espanya, Navidad, and the little island of Alto Vela; by the delineation of its coast; and by an understanding of what Columbus believed about Hispaniola.

One inscription, is Elcezire Izle despanya.

This is a combination of the Arabic word for “island” and the Spanish “isla de españia,” that is, "Spanish Island".

When Columbus discovered this island on the First Voyage he gave it the name “La Isla Española,” meaning "the Spanish Island," subsequently Latinized to “Hispaniola.”

The other name inscribed on the island is Paksin Vidad.

This name is undoubtedly Navidad, the name of the first settlement founded in the New World by Columbus on the north coast of Hispaniola and which occurs on only a few other maps.

The shape and orientation of Hispaniola on the Piri Reis map is strikingly similar to the depiction of the island of Cipango on maps of the fifteenth and Sixteenth centuries.

Cipango was Marco Polo’s name for the islands of Japan, and it was one of the goals sought by Columbus on his first voyage.

Columbus and his contemporaries believed that Cipango was rectangular, with its main axis oriented north to south.

Many maps contemporary with Columbus and Piri Reis show Cipango with this shape and orientation.

Columbus states that when he discovered the island of Hispaniola during his first voyage, he thought he had found Cipango.

Here's a map of what Columbus expected the world to look like.

This is a reconstructed world map from the school of cartography that launched his infamous voyage

The belief regarding the identity of Hispaniola as Cipango persisted into the Sixteenth Century. A note on the Johann Ruysch map of 1508, for instance, states: "....that what the Spaniards call Spagnola is really Cipango ..."

Oronce Fine, on his printed cordiform world map of 1534, labeled Hispaniola as Zipango, i.e., Japan, as did other cartographers who followed him.

By turning the island of Hispaniola on the Piri Reis Map 90 degrees counter–clockwise so that its orientation matches the island in reality rather than Columbus’s conception of Cipango, we can see the coastlines visited and mapped by Columbus.

This is most apparent in the matching coastlines from Bahía de Samaná to Cabo Falso.

The distinctive large bight on the south coast that includes Bahía de Ocoa is well defined.

Notice that the west coast of Hispaniola and the Gulf of Gonave are missing from the Piri Reis depiction of Hispaniola.

This may support Piri Reis's assertion of the Columbian origin of the source map for this region because these western shores of Hispaniola were the only ones never seen by Columbus.

The various inlets, bays, capes, and promontories of the northern, eastern, and southern coastlines of Hispaniola, as seen by Columbus on his first and second voyages, are preserved in the depiction of Hispaniola on the Piri Reis Map.

More than merely a depiction of Cipango, this island on the Piri Reis Map is actually “Hispaniola–as–Cipango” copied from Columbus's map of his voyages and discoveries in the West Indies.

The delineation of Hispaniola on the Piri Reis Map is Columbus's delineation.

Surrounding Hispaniola on the Piri Reis Map are several named islands, some of which can be identified with Columbus.

Birbinish, the name of an island off the south coast of Hispaniola on the Piri Reis Map, is obviously bir binish, Turkish for "long cloak," a translation apparently made by Piri Reis of the island name Alto Velo, Spanish for "high cloak," "high veil,” or "high sail.”

Alto Velo, the sail–like rock island off the southernmost point of Hispaniola, was discovered and named by Columbus during his Second Voyage.

Barbura was one of the names used by the Spanish for the islands and shoals of the Turks Bank immediately north of Hispaniola and this place–name is recorded on the Piri Reis Map.

The Island of Cuba is depicted as part of the mainland on the Piri Reis Map, in accordance with the opinion of Columbus, who believed that Cuba was a great cape of Asia. During the First Voyage he identified Cuba as the mainland of China, even sending an emissary into the interior with a letter from Ferdinand and Isabela to the Grand Khan.

Columbus’s contemporaries — Paolo Toscanelli, Henricus Martellus, Francesco Rosselli, and Martin Behaim — depicted the same view of the Asian mainland on their maps, made between 1474 and 1492.

The Piri Reis Map follows the ideas of Columbus in depicting Cuba as a great cape of the mainland with a coastline that trends north and south.

During his Second and Fourth Voyages Columbus continued to identify Cuba as the mainland of Asia.

Piri’s place-names on the mainland and on the islands offshore all result from Columbus’s second voyage and clearly identify the land as Cuba.

Istonasia appears to be the Spanish "Esta en Asia" that is, "This is in Asia" appropriate words to be found on the map so near to Cuba, which Columbus believed to be the most eastern part of mainland Asia.

Porta Ghande is Puerto Grande, Columbus's name for modern Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, discovered on his Second Voyage.

The Piri Reis Map is the only map that has this Columbian place-name.

The name Kaw Punta Orofay, i.e., Cabo Punta Ornofay, or, "Cape Point Ornofay," is the region on the south coast of Cuba called Ornofay by the natives Columbus found there, also on his Second Voyage.

Or, perhaps, Kaw is Cuba.

This name, Ornofay, as with Puerta Grande, is a place-name linked directly to Columbus, and the Piri Reis Map is the only map to have it.

One of the islands on the map just off the coast of Cuba is named Santa Marya.

This must be the island on the south coast of Cuba named, Santa Maria by Columbus during the Second Voyage.

The prominent cape pointing towards Hispaniola undoubtedly is present-day Cabo Maisi at the eastern end of Cuba.

The region to the north of the cape is that coast on the north side of Cuba explored by Columbus on the First Voyage, and, the region to the south being the south coast of Cuba he explored on the Second Voyage.

Columbus described the north coast of Cuba as mainland extending northwards. He described the south coast of Cuba as extending first westward, from a great cape, and then southward.

The Piri Reis Map follows these descriptions, illustrating Cuba as a mainland with a coastline that tends north and south.

The Piri Reis Map, in the region of Central America or Panama, also has the name Antilia. Piri tells us in his inscriptions that Antilia is the name of the new lands found by Columbus to the west.

This is the origin of the Antilles name for the islands in the West Indies.

Here’s the Central American place-names.

On the section of this mainland to the south, which connects with South America, is a picture of a castle or fortress with an inscription beside it.

This inscription is the Arabic Qal'at feridat, which means "Castle Precious Pearl."

This is a translation by Piri Reis of “Castello Berrucca,” derived from the place-name Veragua and indicates that the source map used by Piri Reis for this section of the map is from after 1504 when Columbus sailed along Panama and picked up the native name Veragua.

Archaeologists know that Vikings reached North America centuries before Christopher Columbus.

And in the top right hand corner of this 15th century chart, said to have been copied from a 13th century original, are the words: “By God’s will, after a long voyage from the island of Greenland to the south toward the most distant remaining parts of the western ocean sea, sailing southward amidst the ice, the companions Bjarni and Leif Eriksson discovered a new land, extremely fertile and even having vines … which island they named Vinland.”

It might fit with our understanding of history, but many believe the Vinland map is simply a 20th-century fake.

The double Virgin Islands (indicating two different source maps were used by Piri Reis in this region) and Qal'at feridat (copied by Piri Reis from a map made after 1504, maybe of Italianorigin) form the two ends of a boundary.

This boundary is between the regions to the south (Puerto Rico, the Lesser Antilles, Central America, and South America), copied by Piri Reis from one or more maps of between 1504 and 1513 that probably included Portuguese maps (as Piri Reis indicates in one of his inscriptions) and possibly Italian copies of Portuguese maps and the regions to the north (the Bahamas, Hispaniola, and Cuba), copied by Piri Reis from a map likely to be the one he claimed was made by Columbus.

Veragua would not be on any map, Columbian or otherwise, anytime before 1504.

And it is unlikely that the double Virgin Islands would be on a map made by Columbus.

The indication is that the region north of the Veragua–Virgin Island boundary line is from the Columbian source map, possibly made in 1495 or 1496 by Columbus or under his direction.

It appears that in his map compilation process in the Caribbean region Piri Reis grafted the Columbian source map of about 1495 or 1496 onto a Portuguese or Italian base map.

The Columbian conception of the transatlantic lands and the Toscanelli–Martellus–Behaim conception of the East Asian coast are combined with the geography of the West Indies and the Caribbean to produce the configurations of the Piri Reis Map configurations that are copied from Columbus's map.

The Piri Reis Map of 1513 and most other maps of the first two decades of the Sixteenth Century depict the results of the attempts at combining the reported geography of the new lands with the differing conceptions of East Asia envisioned by Ptolemy, Marco Polo, Toscanelli, Martellus, Columbus, and the Portuguese. Many of the map’s unique features support statements by Piri Reis that he copied a map by Columbus.

I suggest the Columbian source map used by Piri Reis for his depiction of the Caribbean might have looked something like this.

What appears to be a confused jumble in the northwest section of the map conforms to Columbus’s geographical ideas, particularly those of Hispaniola shaped like Cipango and Cuba shaped as the Asian mainland.

If one reads the writings of Columbus and constructs a map of the lands and islands he discovered based upon the ideas of Columbus that is, that these lands and islands were the Asian mainland and offshore islands and Cipango, as envisioned by Columbus and his contemporaries then one constructs a map of this general configuration.

The most significant aspect of the map is its connection to Christopher Columbus.

The Piri Reis map displays the earliest, most primitive, and most rudimentary cartography of the West Indies, particularly of Hispaniola and Cuba, a primitiveness that indicates that the earliest of all cartographic records of the discoveries in the New World — a map made by Columbus, or made under his supervision, around 1495 or 1496 — is preserved in the Piri Reis map.Links :