South: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Glorious Epic of the Antarctic (1919)

From BFI by Bryony Dixon

Few reels of film can boast an adventure to compare with what happened to the footage from Shackleton’s fateful Antarctic expedition in the 1910s.

It’s been a hundred years since the death of Sir Ernest Shackleton, Britain’s great Antarctic explorer, at the relatively young age of 42.

It’s also over a century since the precious film reels of the 1914 to 1916 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were brought to London by photographer-filmmaker Frank Hurley.

The young Australian survived – thanks largely to Shackleton’s extraordinary determination and leadership skills – and the pictures and films along with him.

The survival of the images is as dramatic a story as the survival of the men.

The Endurance at night, as seen in South:

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Glorious Epic of the Antarctic (1919)

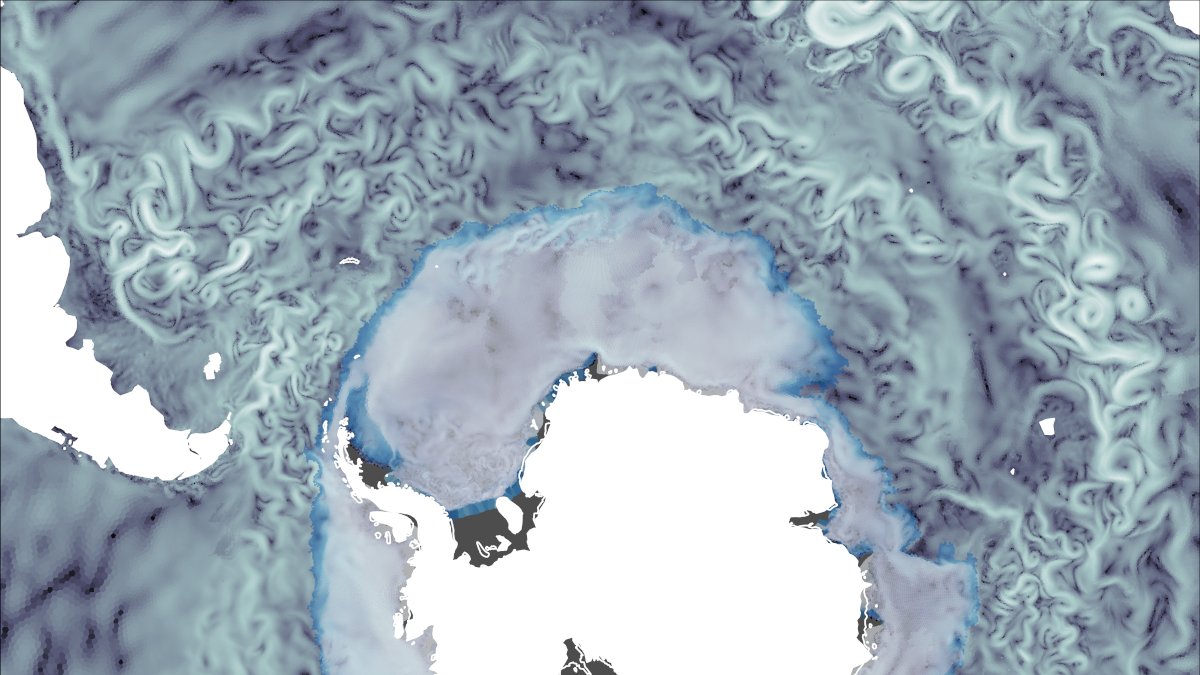

Hurley merrily filmed away as the expedition advanced, with beautiful shots taken at sea, of the pack ice and of the Endurance trying to force passage through the leads.

As the ship became frozen in, he continued to film the work to free her, as well as the setting up of camp on the floating pack ice.

He created extraordinarily inventive shots like one of the rigging lit up at night by magnesium flash.

He captured the gradual destruction and the ship’s final moments as the ice crushed her.

Then the filming stopped as the decision was made to drag the small boats to open water to try to get to land.

There would be no room for heavy cameras, only a couple of pounds per man of personal possessions. The food could be man-hauled across the rough pack ice.

SHIPWRECK HUNT TIME! The @Endurance22 team is trying to find Shackleton’s lost ship the Endurance. Watch this AMAZING 100 yr old expedition footage - courtesy of @BFI who’ve restored & released it as South (1919) - and hear from Mensun Bound on the challenges that lie ahead (1/6) pic.twitter.com/jqwfpZa4wS

— Rebecca Morelle (@BBCMorelle) February 4, 2022

Hurley broke the rules to go aboard the ship and rescue the reels of film and glass slides. It was perilous and nearly got him in trouble with ‘the boss’

He describes the scene:

Early next morning, before the others were astir, Wild and I rejoined him and together we went aboard the Endurance. Poor old ship, what a battered wreck she was! All the cabins along the starboard side had closed up like the bellows of a folding camera. The alleyways were under water and blocked with debris and ice, while the wardroom was crammed to the ceiling with ice blocks and splinters… The refrigerating chamber, which once served as my darkroom, was a wreck of timbers filled with mushy ice. Somewhere in the icy waters lay submerged the hermetically-sealed cases containing my films and negatives. I had been warned not to remove them from the ship owing to the desperate struggle which now lay before us in a march to the land – a march on which food alone could be carried.

He continues:

We hacked our way through the splintered timbers and after vainly fishing in the ice-laden waters with boathooks, I made up my mind to dive in after them. It was mighty cold work groping about in the mushy ice.

But Shackleton, well aware of the paramount importance of returning with images, allowed Hurley to take the film reels and 120 of the glass slides.

As an archivist I can’t help but be impressed by his packing skills.

The fact that exposed negatives survived underwater and produced the beautifully sharp images we see today is extraordinary.

Hurley describes the painful process of selecting which images to keep:

Sir Ernest and I went over the plates together, and as a negative was rejected, I would smash it on the ice to obviate all temptation to change my mind.

Finally, the choice was made, and the films and plates that I considered indispensable were stowed away in one of the boats, having first been placed in double tins hermetically sealed.

About 400 plates were jettisoned and 120 retained.

Later I had to preserve them almost with my life; for a time came when we had to choose between heaving them overboard or throwing away our surplus food—and the food went over!

All my photographic gear was compulsorily abandoned, except one small pocket camera and three spools of unexposed film.

I wonder if three spools of film ever went through more exacting experiences before they were developed.

The same could be said for the three reels of cine film.

And it didn’t stop there – the films and photos with the tiny pocket camera with three unexposed rolls of film made it across the ice to the sea, and through six days and nights in a small cramped boat.

When they reached Elephant Island, the cans were buried in permafrost (they couldn’t have known it, but this was more or less the correct archival thing to do) for four months as they survived, in an upturned boat, burning seal blubber for warmth.

They could have starved or frozen – unable to communicate and on no shipping route, with no knowledge of whether Shackleton and his companions had made it back to civilisation.

Then the miracle happened: Shackleton returned after several unsuccessful attempts to find a ship that could make landfall and bring them off.

It was a great moment as Hurley recalls but even then, the films were on his mind:

Cheer followed cheer, the mountains cheered back, the sun even burst momentarily through the clouds. It was not only the sight of relief that warmed our hearts, for as the little boat drew near, we recognised our long-lost and heroic comrades, Shackleton, Crean, and Worsley!

But there was no time to be lost in greetings, rejoicings and salutations; they could come later when we were safe on board. Our relentless gaolers the icefields were hurrying to close the portals.

Scurrying clouds were drifting over the mountains and obscuring the sun; the wind began to pipe, bleak and gusty. A blizzard was coming; there was not a moment to lose.

Our few scientific specimens and records were gathered, the boxes of negatives and cinematograph films were hastily loaded into a boat, all were to be saved at last.

Even after their rescue, the films could have been lost, as so many silent films were, when their initial distribution period was over.

But there was value in the reels for lecturing by Shackleton and other explorers, including Hurley himself, and the negatives were reused multiple times to tell the story in different ways.

Frank Hurley and Ernest Shackleton

Sir William Jury, a film magnate, bought the footage and rights in 1926, when the ITA expedition went into voluntary liquidation.

He saved the assorted bits of negative and positive, and later reissued it as a sound film, Endurance (1933), with a commentary by Frank Worsley.

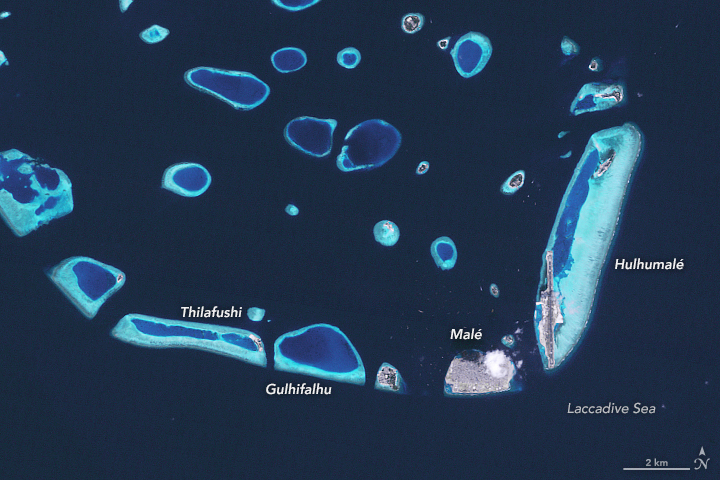

Worsley was the captain of the Endurance and a navigational genius who sailed the Dudley Docker across 800 miles of open sea to south Georgia.

In some ways, probably the greatest risk to the material was the making of the sound version, when the negatives seem to have been re-cut and reframed.

But Jury left them in trust to make sure they were preserved, and they have been held at the BFI since 1955.

In 1996 the silent version was restored as the standalone film we know as South: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Glorious Epic of the Antarctic.

Other vintage prints from around the world were used as a guide for the restoration, while the original reels have returned to sub-zero temperatures in the BFI’s master film store.

With all the bad things that can happen to film stock and the mechanics of cameras in the extremely low temperatures of Antarctica – where the oil freezes jamming the mechanisms and can tear the fragile film – the celluloid seems to have returned in astonishingly good order.

Of course, Hurley only had half a film as the camera was left behind, missing all that drama, and is still presumably home to brittle stars at the bottom of the South Atlantic.

He returned to south Georgia almost immediately in 1916 to take wildlife footage that the newspaper editor Ernest Perris, who sponsored the film, was convinced was needed to make the film interesting to the public (he was not wrong: people were obsessed with penguins).

The story of the escape had to be filled in with titles, drawings and paintings.

South is best thought of as that multi-media documentary lecture that Shackleton would have presented with stills, paintings, film and music woven together to spin the yarn, and for Hurley’s exquisite photography that keeps alive the story of that group of extraordinary men.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Extraordinary 1915 photos from Ernest Shackleton's ... / Antarctic expedition to renew search for Shackleton's ship ... / Will anyone ever find Shackleton's lost ship? / Antarctic Weddell expedition targets Shackleton's lost ship / British scientists in race to find lost shipwreck of Ernest ... / Shackleton's icebound survival story, up close / Shackleton Death or Glory - Rough Seas / Ernest Shackleton voyage to be retraced by modern-day ... / Scott and Shackleton logbooks prove Antarctic sea ice is not ...

Tyler Quales monitoring grow lines in Prince William Sound, Alaska.

Tyler Quales monitoring grow lines in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Limu Hui coordinator Wally Ito shows some limu to participants of the organization’s regular limu walks in Hawai‘i, which help locals connect with local seaweed species.

Limu Hui coordinator Wally Ito shows some limu to participants of the organization’s regular limu walks in Hawai‘i, which help locals connect with local seaweed species.