From Jurist

Edsel Tupaz of Tupaz & Associates says that the dispute over the Spratly Islands highlights several areas of the international law of the seas and complex issues of multilateral diplomacy that must be dealt with in order to resolve the dispute...

Last week, Congressman Eni Faleomavaega of American Samoa introduced

House Resolution 352, which calls for "a peaceful and collaborative resolution to maritime territorial disputes in the South China Sea and other maritime areas adjacent to the East Asian mainland."

On July 8, rallies led by Filipino-Americans were held before key Chinese consulates across the US to protest Beijing's military actions in the

Spratly Islands, which the Philippines considers to be its territory under the

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

Spratly Islands military settlements

picture : Spiridon Manoliu

The July 8 rallies followed the recent

Senate Resolution 217, which unanimously "deplores" China's use of force in South China Sea.

The resolution itemized key flash points relating to disputed maritime territories of the South China Sea.

It listed instances of what the Senate deemed unlawful or illegitimate use of force by the Chinese, and affirmed the US government's commitment to multilateral processes, even as it recognizes that the US is "not a party to these disputes."

Just a few days preceding the resolution, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Philippine Foreign Minister Albert Del Rosario held a

joint press conference affirming the 1951 US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty.

Clinton announced that the US "stands ready to support its ally, the Philippines," amidst escalating tensions over the Spratlys, and proposed a "rules-based regime" under the parameters of UNCLOS.

Clinton added that the US government was keen in "finding ways of providing affordable material and equipment that will assist the Philippine military to take the steps necessary to defend itself.

Following this, the US Navy, jointly with its Philippine counterpart, held a send-off in San Francisco of the BRP Gregorio del Pilar, a 378-foot Hamilton-class cutter, a frigate-class "surface combatant warship" intended to replace the BRP Rajah Humabon, the flagship of the Philippine navy now being decommissioned, which was a US-built World War II Cannon-class destroyer.

According to reports, the Gregorio del Pilar was acquired specifically to patrol the Spratly areas closest to Palawan, a major province of the Philippines, as well as to provide maritime security for ongoing Philippine oil and gas exploration and extraction activities.

The foregoing events constitute the US response to the escalating tensions between China, the Philippines and Vietnam over the Spratlys.

The Spratly Islands have long been a source of conflict between Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.

These islands lie at the heart of one of the world's busiest sea lanes and are known to hold rich oil and natural gas reserves.

Time and again, the Chinese government has insisted that the Spratly dispute should be resolved through bilateral negotiations, while the US and the Philippines, along with the rest of the claimants, call for a multilateral approach.

Either approach will undoubtedly implicate a rules-based regime.

So far there are at least three core international legal codes at play: UNCLOS, the

2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea between China and ASEAN, and the 1951 US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty.

Needless to say, these particular corpuses of law will be operating under a broader set of underlying rules and norms of international law restated in the Geneva Conventions and their precursors, the entire UN system itself, as well as the relevant decisions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) sitting at The Hague.

Even for China there are many legal avenues.

However, the Chinese government's carte blanche declaration that the "South China Sea" belongs to China, without regard to the penumbra of sea-use rights under UNCLOS, is not one of these avenues.

The ways in which one might be able to field a sufficient territorial claim under UNCLOS requires a proffering of technical extrinsic evidence, one will need maritime experts and professionals accustomed to scientific fact finding, all in turn outcome determinative of applicable legal norms.

The salient dispute settlement provisions of UNCLOS are one thing, and marshalling the evidence, quite another.

The great thing about UNCLOS is that it contains everything you need to know about the law of the seas, that is, both substantive law and procedure.

UNCLOS is not clear in this case either, however.

As to the grievance procedure, Article 287 of UNCLOS defines the very courts or tribunals available for dispute resolution to include the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the ICJ, an arbitral tribunal constituted under UNCLOS, or a special arbitral tribunal.

No doubt international lawyers and policy experts will have more than a few words to say about the Spratlys if China were to accede to the compulsory jurisdiction of the UNCLOS courts.

What follows is the attempt to lay out the basic legal and policy norms, restated in the vernacular for laymen and lawyer alike and are listed in order of priority.

Rule One: Just because you can, does not mean you ought to.

Philippine President Benigno Aquino III himself admits that the Philippines, standing alone, is no match for China's military and economic might.

The fact that Chinese military assets can and are being deployed in ways that are not conducive for constructive engagement—as the House and Senate resolutions so indicate—will only further ostracize China from the international community.

There is no doubt that the world needs China as much as China needs the world, and it is plausible to presume that the Chinese government knows this fact.

In legal lingo our Rule One has been expressed generally as preemptory norms under many names, such as pacta sunt servanda (keep to your agreement, and in good faith), the prohibition on the threat of use of force or use of coercion, erga omnes (obligations, despite the absence of treaty law, which are owed to all mankind), right of safe passage, state sovereignty, self-defense and proportionality of means and ends.

However, our first golden rule cuts both ways.

Just because you ought to, does not mean you can.

Suppose the Philippines or Vietnam files suit.

There are hanging questions on whether China, despite being a party to UNCLOS, can be subject to the compulsory (contentious) jurisdiction of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, as well as the legal weight of the tribunal's advisory jurisdiction.

Constraints in time and space leave these questions elsewhere.

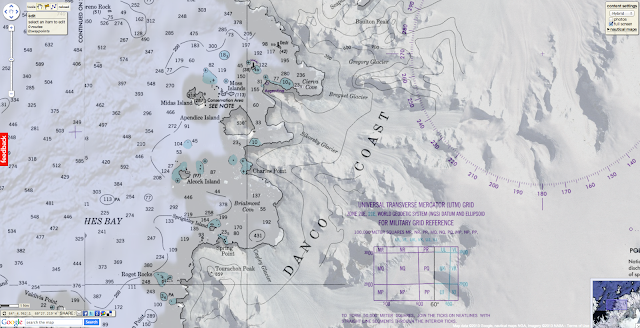

Dangerous and unsurveyed grounds

Rule Two: Do not do (or be too obvious in doing) a classic "divide and conquer."

Even purportedly bilateral issues between two parties in agreements which make no mention of third parties will always function under a multilateral framework, and would almost always implicate an international or foreign law and policy question other than those put to the table.

When Philippine Ambassador Del Rosario raised the Spratlys question with US Senator John McCain in their June meeting, McCain, a former navy officer himself, warned Del Rosario that "China seeks to exploit the divisions among ASEAN members to play them off each other to press its own agenda."

A Washington Post opinion

commented that "China would like the United States to stay out of its disputes with the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, so that it can deal with each of those weaker countries in turn."

There are reasons for the existence of multilateral frameworks, and even bilateral regimes will be subject to unstated (if not disavowed) broader norms which can be brought to bear upon ostensible bilateral dealings.

A good place to start would be the

UN Charter itself.

Clearly the Chinese government knows this, because it sits as a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Even if one can suppose that bilateralism can be self-contained somehow, it will still be difficult to suppose that any Nixon or Kissinger-style bilateral success story can find resonance in this day and age.

It is here where China can learn from the errors of the American past, even if it condemns the US for its "imperialism."

The history of American diplomacy is replete with great narratives and good case studies.

And, if we suppose ourselves worthy of the benefit of hindsight, those catalogues will be a repository of the greatest mistakes of law and war, a rich source for potential lesson drawing for China and for any other nation-state.

In fact, the very use of the term "bilateralism" and the choice of the vernacular of the debate itself can be outcome determinative of whether any third party involvement will draw in such accusations as undue "meddling" or "interfering" in an argument between two people.

On the other hand, greater currency of terms such as "multilateralism" or "multi-party frameworks" might imbue upon the very same phenomenon a more benevolent meaning, converting otherwise hostile interventionism into things like "mediation" or "arbitration."

Given the quickening pace and new dynamics of the Spratlys, and given China's own recognition of the China-ASEAN 2002 Code of Conduct, China might be better off by taking the ASEAN route.

It is smaller, easier to manage, and yet multipartisan.

Rule Three: It is not about the marriage, it is about the money.

Any legal regime should be accorded its own weight, as it is, and in light of its inherent limitations—in Holmesian dictum the international order is not a grand monolithic "overlaw" in which Platonists can find the right answer through sheer remembering.

There are multiple, multi-causal, and multi-directional dynamics at play, and normative argumentation might not catch up to these swiftly changing circumstances, which, no doubt, are clearly empirical and behavioral in nature.

One thing is certain, however:

The profit margin will surely be a bargaining chip if one were to approach the Spratlys question on the right footing.

The six-state jockeying over the Spratlys ultimately hinges on the question of resource-sharing of the world's most important commodity: oil.

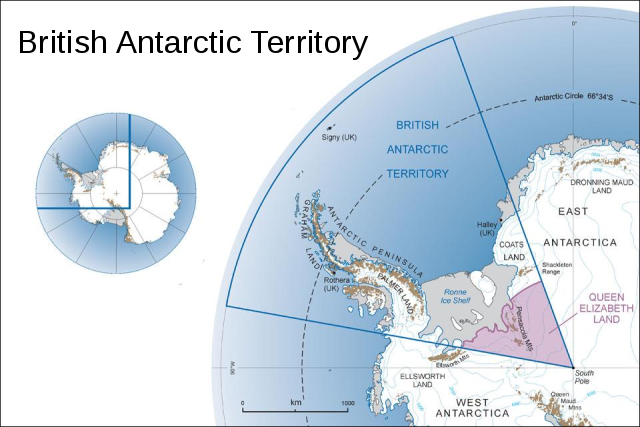

Spratly Islands on Google Maps

Rule Four: It is all on Google Maps.

One account traces Chinese title over the Spratlys—or the entire South China Sea, depending on where you fall in the political spectrum—to an old Han dynasty map circa 110 AD.

An overview of existing scholarship attempts to trace the Chinese claim between 206 BC to 220 AD.

The claim is predicated on the theory that the South China Sea is a Chinese "lake," at least according to the Chinese.

But surely the standards by which we judge ourselves are a whole lot different now than they were back then, and since the 200 BC era there have been changes in cognitive awareness, interruptions of state continuity and existence, varying sovereign assertions and the dissolution of states, including those very states jockeying for the Spratlys today.

(It was once remarked that, through the same logic, Italy today can lay claim to the entire modern world through a Roman map).

What matters, as we stressed, is UNCLOS. UNCLOS contains the substantive law, at least in broad strokes, on how to measure the extent and degree of sovereignty a country or archipelagic state may exercise, and the baselines for each measurement.

Again constraints in time and space leave these questions better discussed elsewhere.

To short cut it all,

just Google it.

It is all there.

Experiment with key phrases like "Spratlys," "Reed Bank" or "Recto Bank," "Palawan," "Zambales," "Paracels," and the like.

Who is closer to what island?

And who is complaining?

The better question is, who is actually there?

Google, and you shall find.

The Reed Bank, now officially called the Recto Bank, lies within the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone, reckoned from the Philippine archipelagic baseline.

The Philippine government, in consortium with private oil companies, has been engaged in gas exploration and production under the Sampaguita project (along with the Malampaya project nearby).

Beyond the Recto Bank, since 1947 Philippine settlers and explorers have occupied main portions of the Spratlys.

Elections for local town officials were in fact held last year.

Filipinos have always referred to the Spratlys as the "Kalayaan" (Freedomland) Island Group.

Not only town elections, but among the six claimants involved in the Spratlys, it is only the Philippines which has an airstrip in the entire Spratly island group.

The airstrip is located on Pag-Asa Island, which is, with very little doubt, part of the Palawan province.

In our recent articles "

China's Imperial Overstretch" and "

China and the Mosquitoes," Daniel Wagner and I have argued that the Spratly island question is ultimately a litmus test for if and when China will begin to act as a responsible member of the international community, willing to engage other contestants in a rules-based regime in accordance with established norms of diplomacy and consistent with a nation of its importance and stature.

It seems that the Chinese government is struggling with this test.

Rule Five: People will always side with the underdog.

We do not have to cite black letter law on this one. In the movies underdogs will always win your sympathy.

While the US has been providing military assistance to the Philippines, this has always been for purposes of capacity building in its counter insurgency operations against Islamic militants in the wake of 9/11.

As the Philippine government decommissions its Vietnam War F-5 fighters, it appears that Secretary Clinton and the US Senate are realigning their assets for something else.

As the US wages war on three fronts, why did the Spratlys find its way to a unanimous Senate resolution while President Obama's bill asking for financial support for Libyan operations

failed to pass muster?

Why did this seemingly unobtrusive smattering of volcanic activity turn out to be the subject of a US Senate resolution?

The Spratlys are just a bunch of islands checkering what appears to be a diamond-shape area beside the Palawan province.

Political will in the US government might have been driven by historical sentimentalism after all, moved perhaps by General MacArthur's famous words, "I shall return."

But ultimately the solution might be more psychic than legal: China needs to get rid of its victim-complex of having been colonized, even imminently dismembered, by Western powers, who, at one time or another, had been colonized by other rulers as well.

Links :