Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), a crucial concept for security, trade, and risk management at sea.

Discover how MDA works, why traditional methods struggle with modern threats, and how AI-powered solutions like Advanced Intelligence elevate maritime monitoring with early anomaly detection, automatic target generation, and seamless end-to-end investigations.

Saturday, June 7, 2025

Friday, June 6, 2025

Humans still haven't seen 99.999% of the deep seafloor

An unidentified cnidarian that resembles a Venus flytrap from the family Hormathiidae, sits at 1874 meters water depth.

A new study finds that the vast majority of the deep sea floor remains undocumented.

NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

From NPR by Neil Greenfieldboyce

An unidentified cnidarian that resembles a Venus flytrap from the family Hormathiidae, sits at 1874 meters water depth.

A new study finds that the vast majority of the deep sea floor remains undocumented.NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Bizarre creatures like vampire squid and blobfish make their home in the dark, cold, depths of the deep sea, but most of this watery realm remains a complete mystery.

That's because humans have seen less than 0.001% of the globe's deep seafloor, according to a new study.

A new study finds that the vast majority of the deep sea floor remains undocumented.NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Bizarre creatures like vampire squid and blobfish make their home in the dark, cold, depths of the deep sea, but most of this watery realm remains a complete mystery.

That's because humans have seen less than 0.001% of the globe's deep seafloor, according to a new study.

This map displays the 2,130 km2 of total observed deep seafloor overlaid on the country of Belgium.

Credit: Ocean Discovery League/Google Maps

Maps created with tools like sonar can show the shape of the seafloor, but it's much harder to send cameras down beyond 200 meters, or more than 656 feet, where sunlight begins to fade rapidly and the waters turn cold and dark.

This is the region of the ocean that's considered "deep."

"The fact of the matter is, when you're down there with a remotely operated vehicle or other sort of deep-submergence vehicle, you can only see a very tiny bit of the deep sea floor at any one time," says Katy Croff Bell of the nonprofit Ocean Discovery League, who led this new research.

She personally has been exploring the deep sea for about a quarter century.

"But it wasn't until about four or five years ago that I thought to myself, well, how much have we actually seen?" she explains.

"And I started trying to find that statistic."

Deep-sea dive activity between 1958 and 2024

Deep-sea dive activity has been concentrated in a small number of locations, particularly Monterey Bay, U.S., Hawai'i, U.S., Suruga and Sagami Bays, Japan, and New Zealand.

The heatmap represents the number of dive activities per 250 km2; the actual area observed on the seabed is too small to represent on a map at this scale.

Credit: Ocean Discovery League

To try to get a better accounting of the total area of the deep seafloor that's been observed so far, she and her colleagues created a database of all known efforts.

They found records of more than 43,000 trips down, starting in 1958, with everything from robotic vehicles to human-driven subs to simple landers that didn't move around.

It turns out that most of the exploratory expeditions occurred within 200 nautical miles of the United States, Japan, and New Zealand.

Those three countries, along with France and Germany, led nearly all of the efforts.

As a result, scientists really haven't seen a very representative sample of what's going on around the globe.

"The Indian Ocean is one of the least explored areas," she says.

Bell says we don't know what habitats might yet be discovered — and that even though the deep ocean might be out of sight and out of mind for most people, the currents down there bring oxygen and key nutrients up towards the surface.

"All of these things are connected, and impact us in so many different ways," she says.

What little has been explored beneath the deep ocean suggests that it can have dramatically different ecosystems that support very different kinds of living things.

Already, in the ocean, explorers have seen hot hydrothermal vents, alkaline vents, and cold seeps.

"But given how little we've seen and how biased it is, we can't really give you a global map of all the habitats of the deep sea, because we just haven't been to all of them," she says.

Since the 1980s, there has been a shift from global, exploratory deep submergence activity in the 1960s and 1970s to a focus on modern-day EEZs or areas that are now within national jurisdiction.

In the 1960s, 51.2% of all dive activities took place in what is now the high seas; In the 2010s, that fraction dropped to 14.9% of all dive activities and dives were mostly concentrated within the EEZs of the United States, Japan, and New Zealand.

Credit: Ocean Discovery League

In the 1960s, 51.2% of all dive activities took place in what is now the high seas; In the 2010s, that fraction dropped to 14.9% of all dive activities and dives were mostly concentrated within the EEZs of the United States, Japan, and New Zealand.

Credit: Ocean Discovery League

For example, in the 1970's, researchers discovered microbes at hydrothermal vents that did not depend at all on the sun and photosynthesis, and instead got their energy from chemical reactions.

"That was completely revolutionary and completely rewrote all the science books," she says.

Geologist and deep sea expert Jeffrey Karson of Syracuse University, who wasn't part of this research team, says this is the first time he's ever seen a well-documented number that really encapsulates what's been seen of the deep ocean floor so far.

He would have assumed the area seen by humanity was less than 1% of the total, he says, but was still surprised the faction would be "such a tiny number."

"We're spending a lot of money to try to understand other planets, maybe planets outside of our solar system.

And yet right here on our own planet, we know so little of what's going on in this area that covers about two-thirds of our planet," says Karson.

"Almost every time we go there, we learn something new and exciting, and many of our discoveries on the seafloor have been serendipitous.

So, you know, we're feeling our way in the dark, literally, there."

Changing how ocean exploration is done will require a focus on developing low-cost technologies that are available to more communities around the world, says Jon Copley, a marine biologist with the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

"If I were a billionaire philanthropist and I wanted to make a real dent in exploring the ocean, then rather than building a kind of superyacht research ship, I would fully back the development and growth of these kinds of low-cost platforms," says Copley.

He says this new study shows that a lot of places on the deep seafloor that are known to be interesting have been visited repeatedly over the years, but that's not a bad thing.

"It's always great to go and see what's over the next rise, what's just out of sight of your pool of light from your deep diving vehicle," he says.

"But there is, of course, an important need to go back to the same place again and again to see how things change over time."

Links :

Thursday, June 5, 2025

The hidden underwater eden of ‘California’s Galapagos’, where seals and grizzly bear-sized bass reign

A harbor seal swims through the kelp forest at Anacapa Island in Channel Islands national park in California in 2019.

Photograph: Douglas Klug/Getty Images

Photograph: Douglas Klug/Getty Images

On the remote Channel Islands, a draw for researchers and divers, preservation has transformed the ecosystem

Just 14 miles (23km) off the southern California coast lies a vast underwater paradise.

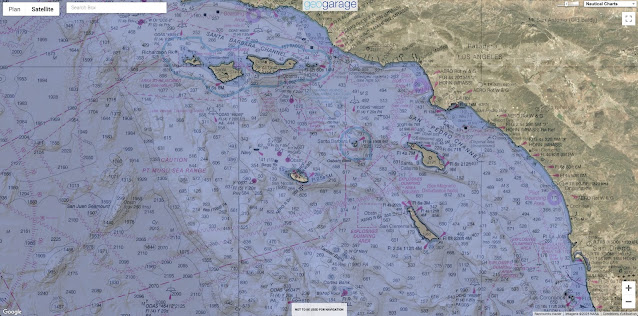

Channel islands in the GeoGarage platform (NOAA nautical raster charts)

Giant sea bass the size of grizzly bears and schools of sardines glide together through swirling strands of golden kelp, whose long stalks preside over a world exploding with life and color.

Playful harbor seals dance into the depths of undulating pink, green and orange plants, alongside spiny crustaceans and vibrant sea stars that embrace the volcanic rock that slopes to the sandy seafloor.

Often called California’s Galapagos, the immersed cliffsides and caves of the Channel Islands are home to thousands of species that thrive on the rugged, pristine and isolated federal parklands and the state-protected waters that surround them.

Playful harbor seals dance into the depths of undulating pink, green and orange plants, alongside spiny crustaceans and vibrant sea stars that embrace the volcanic rock that slopes to the sandy seafloor.

Often called California’s Galapagos, the immersed cliffsides and caves of the Channel Islands are home to thousands of species that thrive on the rugged, pristine and isolated federal parklands and the state-protected waters that surround them.

source : NPS

A lure for research and recreation alike, the 13 designated marine protected areas (MPAs) around the island preserve roughly 21% of their waters as refuge for the species that live there.

While the public can access these areasnear the cities of Santa Barbara and Ventura to swim, surf and dive, fishing and other activities that could result in harm or habitat loss are prohibited.

But some safeguards for this sanctuary are being questioned.

This year, the California fish and game commission is conducting a required review of these MPAs and considering an array of proposals to either expand or reduce protections around the islands.

The marine protected area network, which now covers 124 coastal sections and spans roughly 16% of state waters, was designated with clear goals in mind and with significant buy-in from the public.

Anacapa Island in the Channel Islands in 2019.

Photograph: Antonio Busiello/Alamy

With the MPAs’ first 10-year review under way, California officials are evaluating whether they have been successful at sustaining marine life and ecosystems, maintaining educational, recreational and spiritual use and minimizing economic loss.

Twenty petitions have been filed by stakeholders – tribes, fisheries and recreators among them – and are being taken into consideration.

Decisions are expected early next year.

Scientists, conservationists and environmental advocates hope the abundance that has flourished here proves the value of preservation.

“We have had two decades of opportunity to learn from the lab of protected areas at the Channel Islands,” said Dr Douglas McCauley, associate professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. He called the area “an economic tool”.

With fewer than 290,000 visits to the Channel Islands in 2024, the park is far less trafficked than other loved-to-death outdoor attractions in California (by comparison, Yosemite hosted more than 4.3 million visits last year).

But the five remote islands, reachable only by boat, offer a rare glimpse into a wilder world.

There are no paved roads, no rental shops and no gift shops, and many of the buildings are of historical and cultural relevance rather than being for visitor use.

It’s this untouched experience that lures adventure-seekers across the channel and into the surf, where the rich biodiversity cultivated by conservation is the primary draw – especially beneath the waves.

“People come from around the state and around the world to dive the Channel Islands, drawn by playful sea lions, underwater cathedrals of emerald kelp forests and giant sea bass weighing four times more than the divers themselves,” said Molly Morse, senior manager at Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, speaking about a 2023 study she did that showed MPAs drive ecotourism dives.

But the benefits spread beyond drawing hardy tourists, according to McCauley.

Barring fishing in specific spaces has not only helped species bounce back – it has also been a boon for the fishing industry.

Speaking over the loud hum of a dive boat engine as it churned through the expanse of blue toward the islands, McCauley likened the regulations to a savings account that generates exponentially higher returns.

“When you leave some of this biodiversity without harvesting it, it grows in number but it also grows in size,” he said.

Allowing creatures to grow larger means they will produce more eggs and fuel a bounty of biodiversity that spills over into areas where fisheries, recreation and ecosystem recovery can all benefit.

“A very large sheephead,” he said, referring to a uniquely featured fish with a pink middle and large, protruding teeth, “that maybe has the mass of two smaller females, produces far more than just twice the number of eggs.”

Even on the surface on a cold, grey day in May, the area bounds with life.

As the coastal communities on the mainland fade against the horizon, scores of dolphins spring through the surf under a cacophony of hungry gulls.

A humpback flashes its sides and tail before emerging face-first to gulp its lunch.

A humpback whale, dolphins and sea birds feed on a school of fish in the Channel Islands on 1 May 2025.

Photograph: Annika Hammerschlag/AP

Photograph: Annika Hammerschlag/AP

But it’s more than just observed abundance.

The extensively studied areas have proven able to feed and fuel nearby fisheries.

Lobster production alone increased by 225% outside of its boundaries, according to McCauley.

Meanwhile, biomass increased by 80% and a study of fish species documented a 50% jump within protected zones in just five years after the MPA designation.

Still, expanding the protections could prove challenging.

Commercial fishers are largely supportive of ensuring ecosystems are sustainable but less keen on seeing their rights to more marine areas revoked.

Craig Shuman, marine region manager at the California department of fish and wildlife, told the Associated Press that the marine protected areas are among the most controversial things the agency works on.

Last year, a range of stakeholders, which included fisheries, tribes, conservationists and recreators submitted 20 petitions with a range of suggestions, from decreasing or eliminating MPAs to enhancing and improving them.

The petitions are under consideration by the commission.

The political tides are also turning and conservation objectives are increasingly on the chopping block.

The Trump administration has rolled back regulations on roughly 500,000 sq miles (1.3m sq km) of federal waters, opening once-protected areas to commercial fishing.

The president has promised that more actions are on the way.

Meanwhile, the threats continue.

The climate crisis has added new challenges with dangers from disasters including fire-debris run-off, increased pollution and the changes caused by a warming world.

“When we protect the ocean, we are really taking care of ourselves,” said Sandy Aylesworth, director of the Pacific Initiative at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

She is hopeful that the MPAs will not only be reinforced but expanded: among the proposals are five new MPAs and eight expansions, including four that would make current regulations even more restrictive.

The extensively studied areas have proven able to feed and fuel nearby fisheries.

Lobster production alone increased by 225% outside of its boundaries, according to McCauley.

Meanwhile, biomass increased by 80% and a study of fish species documented a 50% jump within protected zones in just five years after the MPA designation.

Still, expanding the protections could prove challenging.

Commercial fishers are largely supportive of ensuring ecosystems are sustainable but less keen on seeing their rights to more marine areas revoked.

Craig Shuman, marine region manager at the California department of fish and wildlife, told the Associated Press that the marine protected areas are among the most controversial things the agency works on.

Last year, a range of stakeholders, which included fisheries, tribes, conservationists and recreators submitted 20 petitions with a range of suggestions, from decreasing or eliminating MPAs to enhancing and improving them.

The petitions are under consideration by the commission.

The political tides are also turning and conservation objectives are increasingly on the chopping block.

The Trump administration has rolled back regulations on roughly 500,000 sq miles (1.3m sq km) of federal waters, opening once-protected areas to commercial fishing.

The president has promised that more actions are on the way.

Meanwhile, the threats continue.

The climate crisis has added new challenges with dangers from disasters including fire-debris run-off, increased pollution and the changes caused by a warming world.

“When we protect the ocean, we are really taking care of ourselves,” said Sandy Aylesworth, director of the Pacific Initiative at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

She is hopeful that the MPAs will not only be reinforced but expanded: among the proposals are five new MPAs and eight expansions, including four that would make current regulations even more restrictive.

Underwater kelp forests at Anacapa Island in Channel Islands national park in California.

Underwater kelp forests at Anacapa Island in Channel Islands national park in California.Photograph: Douglas Klug/Getty Images

“There are also proposals that would weaken the network,” she said, noting the strong headwinds conservation proposals face locally and across the country.

With initial recommendations from the department of fish and wildlife not expected until November, there’s not a strong signal which way things will go.

Until then, the research will continue, as will fishing along the spillover zones where species are bountiful.

Divers will swim among the rare and vibrant creatures in the depths.

Birds will watch them from perches atop the craggy rocks.

For McCauley, that’s already a tremendous achievement.

But he thinks there’s more to do.

“This amazing park is still a baby park,” he said, comparing the 20-year-old Channel Islands national park to the 152-year-old Yellowstone.

“This is just a glimpse,” he said.

“Imagine what these values can be if maximized for several generations – for another century of Californians.

That is what I would love to challenge ourselves for today.”

Wednesday, June 4, 2025

Marine Corps could be among first users of electric wing-in-ground craft

REGENT Seagliders: A Perfect Fit for Coastal Defense Missions

As a true dual-use company, we are proud to announce that REGENT has signed an agreement with the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab (MCWL) to demonstrate seaglider technology for defense logistics operations.

As a true dual-use company, we are proud to announce that REGENT has signed an agreement with the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab (MCWL) to demonstrate seaglider technology for defense logistics operations.

The entire team at REGENT is motivated by the fact that our vessels could save lives, help accomplish critical missions, or play a role in deterring conflict altogether Ret. General Robert Neller, who served as the 37th Commandant of the United States Marine Corps and now sits on REGENT’s Defense Advisory Board stated: “REGENT seagliders provide the ability to distribute multiple capabilities in the littorals, including logistics, command and control, and ISR. The REGENT seaglider capabilities will create success.”

This is a another major milestone to bringing seagliders to market; we're eager to demonstrate their ability to operate in each their modes of operation (float, foil, fly), and understand the vessel's potential in military operations, including maneuver and transport operations.

From The Maritime Executive

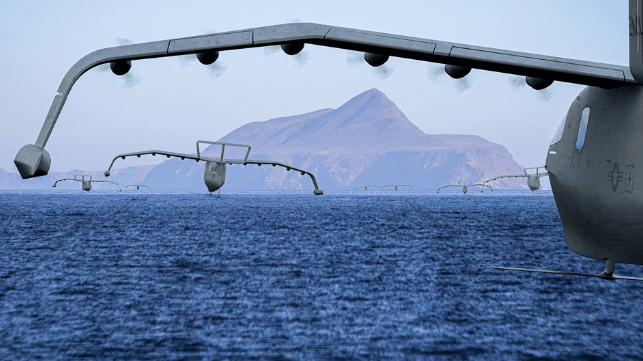

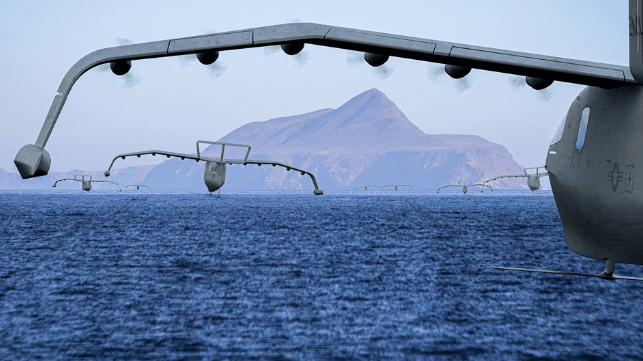

The U.S. Marine Corps is exploring the idea of buying Regent's new all-electric wing-in-ground (WIG) craft to move troops around in the littorals of the Pacific Islands, the service's R&D lab told media at a conference in D.C. last week.

The Marine Corps' new fighting doctrine - Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations - is designed for conflict in the First Island Chain, in and around the small islands near Taiwan.

In the event of a cross-strait invasion, small teams of heavily-armed marines would fan out to unimproved outposts south of Okinawa, where they would be well-positioned to harass Chinese warships with long-range missiles.

The strategy depends on logistics to move these teams into remote locations, resupply them, and relocate them on the fly to keep ahead of the enemy.

This requires a new fleet of landing craft, drones, and other methods of short-range transportation.

One novel transport mode could be advantageous in a fight, the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL)'s Matthew Koch told TWZ: an all-electric WIG craft.

Illustration courtesy Regent

One novel transport mode could be advantageous in a fight, the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL)'s Matthew Koch told TWZ: an all-electric WIG craft.

Koch's team is looking closely at Regent's Viceroy Seaglider, a 12-seat passenger craft designed to hit speeds of 180 knots on pure battery-electric power.

REGENT Craft reveals the first full-scale seaglider prototype, a novel high-speed maritime vessel that connects coastal destinations.

The Rhode Island-based developer and manufacturer of seagliders completes the first on-water tests of the prototype with humans onboard, kicking off a testing campaign that will culminate in the first human seaglider flight mid-year

Like other WIG designs, the Seaglider stays close to the surface and does not require FAA pilot licensing for operation.

Unlike other WIG craft, it is whisper-quiet and cool-running because of its electric motors.

This would give marines a fast, low-heat-signature, below-the-radar method to sneak into or out of remote sites.

The first Regent Viceroy prototype began sea trials earlier this year.

The first Regent Viceroy prototype began sea trials earlier this year.

First commercial delivery is expected in 2027, and Regent says that it has secured billions in commercial preorders.

The Marine Corps has put down $10 million for a parallel military demonstration program, on top of a $5 million initial R&D contract.

The Marine Corps has put down $10 million for a parallel military demonstration program, on top of a $5 million initial R&D contract.

Tuesday, June 3, 2025

Seawise Giant: history and legacy of the world’s largest ship

The Largest Ship In The World Has A GIANT Problem.

The Seawise Giant, known as an Ultra Large Crude Carrier, was the longest and heaviest ship to ever set sail in the world.

However, despite its massive size, it faced a variety of limitations that ultimately made it fall into obscurity.

It was also a prime target during one of the most intense conflicts of the past fifty years.

From Pulse by Andrey Chernov

Now, imagine a ship so long she could stretch nearly the full length of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool in Washington, D.C. , and still have room at both ends for tourists to take selfies.

The

Seawise Giant was the longest and heaviest ship ever constructed,

measuring 1,504 feet in length and with a cargo capacity exceeding a

staggering 564,000 tons

SeaWide Giant (earlier Oppama; later Happy Giant, Jahre Viking, Knock Nevis, and Mont)

That was the Seawise Giant, the longest, heaviest, oil-slicked leviathan ever to roam the oceans under her own power.

Scrapped in 2010, she’s long gone, but her story is still too big to ignore.

At 458.45 meters (1,504 feet), the Seawise Giant was longer than the Empire State Building is tall.

At 458.45 meters (1,504 feet), the Seawise Giant was longer than the Empire State Building is tall.

She could haul over 4 million barrels of crude oil in one go, enough to meet the daily demand of France or Germany.

But size came at a price.

But size came at a price.

She was too large to fit through the Suez Canal, Panama Canal, or even the English Channel.

That meant longer voyages, often around the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn, just to get from A to B. Imagine planning every voyage knowing half the world’s shortcuts are closed to you.

Originally commissioned in 1974 by a Greek businessman, the ship was left half-built in a Japanese shipyard after the buyer backed out.

Originally commissioned in 1974 by a Greek businessman, the ship was left half-built in a Japanese shipyard after the buyer backed out.

Enter Tung Chao-yung, a Hong Kong shipping magnate with a flair for big moves and subtle puns.

He snapped up the abandoned behemoth and extended her even further.

The name “Seawise” was a play on his own initials — C.Y.’s — a wink for those paying attention. Under Tung’s direction, the already massive vessel was enlarged, strengthened, and fitted with the era’s most advanced tech: a sophisticated ballast system, high-strength steel, and a single enormous propeller to push her through the water.

But that propeller guzzled fuel, 1,660 barrels of oil a day when fully loaded, turning every voyage into a financial balancing act.

In 1988, the Seawise Giant was caught in the crossfire of the Iran-Iraq War.

The name “Seawise” was a play on his own initials — C.Y.’s — a wink for those paying attention. Under Tung’s direction, the already massive vessel was enlarged, strengthened, and fitted with the era’s most advanced tech: a sophisticated ballast system, high-strength steel, and a single enormous propeller to push her through the water.

But that propeller guzzled fuel, 1,660 barrels of oil a day when fully loaded, turning every voyage into a financial balancing act.

In 1988, the Seawise Giant was caught in the crossfire of the Iran-Iraq War.

While anchored off Larak Island, she was hit by Iraqi missiles and severely damaged.

Most ships would’ve been lost, but not her.

She was salvaged, repaired, and returned to duty, reborn again and again under new names: Happy Giant, Jahre Viking, Knock Nevis, and finally FSO Asia.

That last name came with a new role, as a Floating Storage and Offloading (FSO) unit off Qatar.

That last name came with a new role, as a Floating Storage and Offloading (FSO) unit off Qatar.

Instead of sailing, she stored and offloaded oil offshore, adjusting to the changing demands of a shifting industry.

Despite her mammoth size, the Seawise Giant operated with a crew of just 40.

Despite her mammoth size, the Seawise Giant operated with a crew of just 40.

Thanks to automation and clever design, she didn’t need more.

That efficiency showed just how far shipbuilding had come, and how much could be done with less.

Still, navigating and docking her required special facilities and planning.

Still, navigating and docking her required special facilities and planning.

She couldn’t pull into just any port.

Offshore transfers were often her only option, adding layers of complexity to her operations.

In her prime, the Seawise Giant helped stabilize oil markets by moving massive quantities in a single voyage.

In her prime, the Seawise Giant helped stabilize oil markets by moving massive quantities in a single voyage.

She reduced the number of trips needed, lowered costs per barrel, and cushioned markets against short-term shocks.

But her size also made her inflexible.

Long routes meant high fuel consumption, and changing environmental regulations started shifting the economics.

By 2009, she was more costly to run than the market could justify.

Final Voyage.

She made her last journey to Alang, India, the world’s largest ship-breaking yard, where she was dismantled.

Her 36-ton anchor now sits at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, a relic of ambition and steel.

The Seawise Giant wasn’t just a ship, she was a statement.

Her legacy lives on in ship design, maritime safety, and fuel-efficiency debates.

From her 564,763 deadweight tons to her record-breaking length, she pushed engineers to rethink limits.$

Largest ships

And though it’s unlikely we’ll see ships quite like her again, the world has turned toward sustainability, flexibility, and smaller footprints, her story still inspires.

In a world of constant change, she reminds us that human ambition floats best when balanced with wisdom.

Links :

In a world of constant change, she reminds us that human ambition floats best when balanced with wisdom.

Links :

- Interesting Engineering : Seawise Giant: The rise, rebirth, and fall of the world’s longest ship

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/etimes/trending/this-is-what-happened-to-the-worlds-biggest-ship-ever-built/photostory/107731936.cms

- https://orbitshub.com/the-majestic-seawise-giant-a-journey-of-triumphs-and-tragedies/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seawise_Giant

- https://www.virtuemarine.nl/post/seawise-giant-the-colossal-supertanker-of-the-seas

- https://testbook.com/static-gk/largest-ship-in-the-world

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/seawise-giant

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Seawise_Giant

- https://gcaptain.com/mont-knock-nevis-jahre-viking-worlds-largest-tanker-ship/

- https://www.woodenmodelboat.com/model/woodpro/all/seawise_giant.htm

- https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2024/4/9/2230965/-Hidden-History-The-Largest-Ship-Ever-Built

Monday, June 2, 2025

Debunking geodetics in specifications : horizontal and vertical coordinate reference systems

Figure 4: World-wide sea-level rise between 1992 and 2019.

Figure 4: World-wide sea-level rise between 1992 and 2019.(Image courtesy: NASA)

From Hydro by Huibert-Jan Lekkerkerk

The basis of any construction or charting project is the definition of an unambiguous, retrievable horizontal and vertical coordinate reference system (CRS).

This should be included in the contract specifications.

Nothing new here, but procedures from the past may no longer be suitable with modern positioning techniques such as PPP GNSS.

While the horizontal CRS can be difficult, the vertical often poses even more of a problem due to ambiguous references during the design of a construction.

Even when defined unambiguously, retrieving vertical reference levels is still difficult.

In this article, I describe some of the issues from a hydrographic viewpoint, focusing on geodetic issues that should be addressed in the specifications.

Specifying a horizontal CRS

The horizontal CRS specifies how the results from the survey should be provided to the client.

Often, this is a regional or national projected CRS such as the UTM projection.

A projection alone is not enough and should be accompanied by a horizontal datum.

This horizontal datum is often not the same as that provided by the positioning system (GNSS) and thus in addition a datum transformation with accompanying parameters is required.

The most common datum transformation requires seven parameters.

This datum transformation requires particular attention.

Many people ‘assume’ that the output from a GNSS is in the WGS84 datum.

Looking at for example the NMEA0183 specification, which even states this, this is logical.

However, the output CRS of a GNSS receiver is directly tied to the CRS of the augmentation system.

An absolute GNSS (unaugmented GNSS, code phase dGNSS and PPP) outputs its positions according to a worldwide CRS.

This can be WGS84, but most PPP systems output ITRF-based positions.

Though WGS84 is kept to within 10cm of ITRF, there are some small differences which might be noticeable with PPP.

To make matters worse, the Earth is not stable and, because of continental drift, ITRF (but also WGS84) is recomputed on a regular basis with the last iteration (epoch) being ITRF2020.

RTK outputs its coordinates in a CRS that is directly tied to the specified coordinates of the base station or network.

In general, RTK is tied into a regional CRS such as ETRS89 in Europe or NAD83 in the US.

The CRS used by a relative system drifts with the continental plate it is fixed to and as such horizontal positions on a regional CRS are relatively stable over time.

Nevertheless, they are not fully stable due to changes in the plate orientation and new realizations (epochs) are created at intervals.

Datum transformations

This brings us to the issue of the datum transformation parameters.

The output datum is effectively defined through the input datum from the GNSS and the datum transformation used.

Different realizations of a horizontal datum require adjusted datum transformation parameters.

The seven-parameter shift itself does not compensate for continental drift and as such the accuracy deteriorates over time (within a single survey a semi-constant error).

This requires regular updates of the datum transformation parameters, something not necessarily done with copy-paste specifications.

The alternative is 14-parameter shifts, which include the seven parameters and their change over time.

These parameters can be used for a longer time but still need to be tied to the datum given from the GNSS receiver, which in turn depends on the augmentation used.

The horizontal CRS specifies how the results from the survey should be provided to the client.

Often, this is a regional or national projected CRS such as the UTM projection.

A projection alone is not enough and should be accompanied by a horizontal datum.

This horizontal datum is often not the same as that provided by the positioning system (GNSS) and thus in addition a datum transformation with accompanying parameters is required.

The most common datum transformation requires seven parameters.

This datum transformation requires particular attention.

Many people ‘assume’ that the output from a GNSS is in the WGS84 datum.

Looking at for example the NMEA0183 specification, which even states this, this is logical.

However, the output CRS of a GNSS receiver is directly tied to the CRS of the augmentation system.

An absolute GNSS (unaugmented GNSS, code phase dGNSS and PPP) outputs its positions according to a worldwide CRS.

This can be WGS84, but most PPP systems output ITRF-based positions.

Though WGS84 is kept to within 10cm of ITRF, there are some small differences which might be noticeable with PPP.

To make matters worse, the Earth is not stable and, because of continental drift, ITRF (but also WGS84) is recomputed on a regular basis with the last iteration (epoch) being ITRF2020.

RTK outputs its coordinates in a CRS that is directly tied to the specified coordinates of the base station or network.

In general, RTK is tied into a regional CRS such as ETRS89 in Europe or NAD83 in the US.

The CRS used by a relative system drifts with the continental plate it is fixed to and as such horizontal positions on a regional CRS are relatively stable over time.

Nevertheless, they are not fully stable due to changes in the plate orientation and new realizations (epochs) are created at intervals.

Datum transformations

This brings us to the issue of the datum transformation parameters.

The output datum is effectively defined through the input datum from the GNSS and the datum transformation used.

Different realizations of a horizontal datum require adjusted datum transformation parameters.

The seven-parameter shift itself does not compensate for continental drift and as such the accuracy deteriorates over time (within a single survey a semi-constant error).

This requires regular updates of the datum transformation parameters, something not necessarily done with copy-paste specifications.

The alternative is 14-parameter shifts, which include the seven parameters and their change over time.

These parameters can be used for a longer time but still need to be tied to the datum given from the GNSS receiver, which in turn depends on the augmentation used.

Figure 1: Average continental plate drift.

Figure 1: Average continental plate drift.(Image courtesy: NASA)

Often, the datum transformation parameters quoted do not match the output datum from the GNSS receiver.

For example, the Netherlands uses an ETRS89 to Bessel 1841 datum transformation inshore and nearshore.

If RTK is used, this requires a check of the ETRS89 epoch in the RTK network and a selection of the appropriate datum transformation parameters in the software.

However, matters are more complicated if PPP is used.

In this case, we have an ITRF2020 output that needs to be transformed to ETRS89, which then needs to be transformed to Bessel 1841.

Ignoring the first step results in errors of around nine decimetres, which is too much for most construction projects.

Specifications usually quote ETRS89 to Bessel 1841 conversion (through a combined ‘RDNapTrans’ conversion set) and most (all?) survey software can only handle a single conversion.

So, how to deal with the first step?

Some GNSS receivers have the internal option to do a datum transformation.

While this is technically not allowed by the NMEA0183 protocol, it does solve an issue.

In this case, the ITRF2020 to ETRS89 (check the epoch!) is done in the GNSS receiver and the ETRS89 to Bessel 1841 in the survey software.

However, not all receivers have this option.

The alternative is to perform a ‘block shift’ in the survey software.

Most software allows this on the projected coordinates.

In this case, the first datum transformation is computed as a dE, dN shift in UTM (or other chart projection) and applied to the transformed coordinates.

For an area of a few tens of kilometres wide, the resulting error is limited to the cm-level and usually acceptable.

LAT and MSL

If the horizontal datum is complicated, the vertical datum is even more so.

Depending on the type of project, a tide-derived datum is often specified such as ‘LAT’ or ‘MSL’.

The former is also recommended by the IHO as vertical reference (or a level close to this).

There is however no such thing as LAT or MSL.

Or, as the EPSG database states for MSL (and LAT): “Approximate because not specific to any location or epoch.

Users are advised to not use this generic CRS but instead use one with a specific datum origin (e.g.

‘Mean Sea Level at xxx during yyyy-yyyy’) or defined through a specified geoid/hydroid model.”

In other words, tidal-based vertical datums should be specified for a specific place and with a specific epoch on which they are based.

For MSL, this is easy to understand as we have all heard about sea-level rise.

On average, MSL rises 4mm/year but this change is not the same for every location.

LAT varies even more from location to location as it depends on the shape and amplitude of the tidal curve.

As a result, LAT can change significantly (decimetres to metres) over just a few kilometres of coastline whereas MSL is relatively stable.

If the horizontal datum is complicated, the vertical datum is even more so.

Depending on the type of project, a tide-derived datum is often specified such as ‘LAT’ or ‘MSL’.

The former is also recommended by the IHO as vertical reference (or a level close to this).

There is however no such thing as LAT or MSL.

Or, as the EPSG database states for MSL (and LAT): “Approximate because not specific to any location or epoch.

Users are advised to not use this generic CRS but instead use one with a specific datum origin (e.g.

‘Mean Sea Level at xxx during yyyy-yyyy’) or defined through a specified geoid/hydroid model.”

In other words, tidal-based vertical datums should be specified for a specific place and with a specific epoch on which they are based.

For MSL, this is easy to understand as we have all heard about sea-level rise.

On average, MSL rises 4mm/year but this change is not the same for every location.

LAT varies even more from location to location as it depends on the shape and amplitude of the tidal curve.

As a result, LAT can change significantly (decimetres to metres) over just a few kilometres of coastline whereas MSL is relatively stable.

Figure 2: Horizontal (blue) and vertical (red) effect of continental drift between ETRS89 and WGS84 for the Netherlands.

Figure 2: Horizontal (blue) and vertical (red) effect of continental drift between ETRS89 and WGS84 for the Netherlands.GNSS heights and the vertical datum

This is however only one aspect of the vertical datum.

Nowadays, many projects are performed using GNSS for height measurements (RTK or PPP GNSS).

As stated above, these output their position in a global (ellipsoidal) datum.

However, most projects are not interested in ellipsoidal heights but require ‘something’ related to either an onshore datum or a tidal reference.

To convert an ellipsoid height to an onshore, geoidal (orthometric) datum, a geoid-ellipsoid separation model is required.

Though often stated to be the same, MSL and the geoid are not identical.

Where the geoid is based on gravity, MSL is (traditionally) based on actual tidal measurements.

The differences depend on the geoidal (onshore datum) definition but also on the tidal behaviour.

The changes over time between the two not only depend on sea-level rise but also on land subsidence (or indeed uplift), where the onshore datum can be influenced by geological changes (depending on how it is defined).

As a result, GNSS heights need to be transformed from ellipsoid heights to geoidal heights and from thereon to an MSL or LAT value using a separation model.

For some areas in the world, models exist that allow direct transformation from a GNSS datum to a LAT or MSL value.

For other areas, two separate corrections or models are required, one to derive the geoid height from the GNSS datum and another to determine MSL or LAT from the geoid.

Though differences between the height as derived from different GNSS datums are small (cm-level), they have a systematic effect nonetheless.

Different models for deriving LAT and MSL potentially give different answers, even without regarding MSL rise and the accompanying LAT rise (relative to the GNSS datum – geoid).

Figure 3: Average world-wide sea-level rise per month over the last 30+ years.

(Image courtesy: NASA)

Obtaining vertical offset values

(Image courtesy: NASA)

Obtaining vertical offset values

It is possible to derive a local geoid-ellipsoid separation at relatively little cost providing at least one benchmark is available.

The GNSS height should be recorded over this benchmark (preferably over an extended period, say 24+ hours) and when compared to the given benchmark height will provide an offset for that point.

Using a levelling campaign around the project will allow further determination of additional points.

Thus, with relatively small effort, a crude but effective local geoid-ellipsoid separation model can be created.

Deriving a local geoid-LAT offset requires tidal measurements with a tide gauge tied into the local, onshore datum.

For a proper harmonic analysis, at least 18.6 years of data (continuous) are required.

It is not impossible to derive LAT from shorter time series, but these have an inaccuracy that depends on how representative the conditions are for that period.

For example, a 30-day measurement period can be influenced by short-term meteorological events such as storms and will not include seasonal influences.

A 30-day harmonic analysis has an accuracy of centimetres to decimetres from the long-period LAT value.

A year’s worth of measurements will provide a more stable value.

If the project is short enough, a single value is sufficient.

For longer projects or tidal measurements from some time ago, MSL rise should be incorporated in the vertical offset.

Specifications and geodetics

When writing specifications, all the above should be considered but not necessarily be solved by the specifier.

The output horizontal CRS (including the local datum) should be specified, but the datum transformation can be left to the contractor if a control point coordinate is provided by the client on which the contractor can verify that the datum transformation has been implemented correctly.

Alternatively, the specifier should state the exact datums and parameters to be used and keep these updated for consecutive projects.

The vertical datum should be specified using location and reference epoch or alternatively through a model (clearly stating which input and output from the model is required).

It is advised to keep models constant for consecutive projects providing sea-level rise is not an issue.

When switching between models, an investigation into the effects should be made.

Sunday, June 1, 2025

Image of the week : busiest yacht gatherings

This year’s Monaco GP was one of the busiest yacht gatherings.

On Race Day, there were 98 yachts over 24m anchored off Monaco, 42 more in Beaulieu-sur-Mer, and 122 docked in Port Hercules.

70 yachts were anchored off Monaco during the Grand Prix in 2024, compared to 61 in 2023 and just 31 in 2022, showing the event is definitely growing in popularity.

70 yachts were anchored off Monaco during the Grand Prix in 2024, compared to 61 in 2023 and just 31 in 2022, showing the event is definitely growing in popularity.

The iconic Formula 1 race transforms Monaco’s harbour into a spectacular floating luxury marina, attracting some of the world’s largest and most prestigious superyachts.

These yachts offer exclusive vantage points for race viewing, seamlessly blending the thrill of high-performance motorsport with the sophistication of the high-end yachting lifestyle.

The Monaco Grand Prix, which this year happened from 23rd to 25th May, has seen a dense aggregation of pleasure boats and superyachts concentrated near the circuit.

For this event, large passenger ships, including the Explora II (IMO: 9869887), made calls at Port de Monaco during their Mediterranean itineraries.

For this event, large passenger ships, including the Explora II (IMO: 9869887), made calls at Port de Monaco during their Mediterranean itineraries.

Currently berthed at the passenger jetty, the Explora II is valued on our platform at $550 million.

The exposure at jetties in Port de Monaco and offshore has more than tripled to nearly 2,000 pleasure boats currently in the Hercules port and offshore.

Skytek’s Real World platform identifies 170 yachts exceeding 50 meters in length, including several high-value vessels such as the $360 million Kismet, $200 million Renaissance, $150 million Symphony, $150 million Vava II, and the $100 million Atlantis II.

The exposure at jetties in Port de Monaco and offshore has more than tripled to nearly 2,000 pleasure boats currently in the Hercules port and offshore.

Skytek’s Real World platform identifies 170 yachts exceeding 50 meters in length, including several high-value vessels such as the $360 million Kismet, $200 million Renaissance, $150 million Symphony, $150 million Vava II, and the $100 million Atlantis II.

Together, these yachts contribute to an estimated total aggregated value surpassing $3.5 billion.

2025 Monaco GP may set yacht record

— MarineTraffic (@MarineTraffic) May 22, 2025

The Monaco Grand Prix this weekend could see a record number of yachts visiting the area, trying to catch a glimpse of the race.

The 2025 edition of the race could extend a multi-year rise in yacht arrivals, following a record 466 pleasure… pic.twitter.com/p0SLxROWEN

The only other occasion that pops to mind was this past New Year’s in St. Barts, when 148 superyachts were anchored there.

There are 148 yachts currently set to celebrate New Year’s in St. Barts, making it by far the most popular yachting destination for New Year’s celebrations.

There are 148 yachts currently set to celebrate New Year’s in St. Barts, making it by far the most popular yachting destination for New Year’s celebrations.And there’s still more yachts coming!

2021: A dazzling start to the tradition, with luxury yachts filling the harbor

2021: A dazzling start to the tradition, with luxury yachts filling the harbor 2022: Even more arrivals

2023: Noticeably fewer visitors (why?)

2024: A record-breaking year!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)