line that separates day and night is called the terminator and also the "twilight zone.

— Science girl (@gunsnrosesgirl3) August 8, 2025

Here you can say night and day together, on the left it's still day (the sun is still shining) and on the right it's already a dark night with the moon.

pic.twitter.com/nhHHvKac1T

Saturday, August 9, 2025

The twilling zone

Friday, August 8, 2025

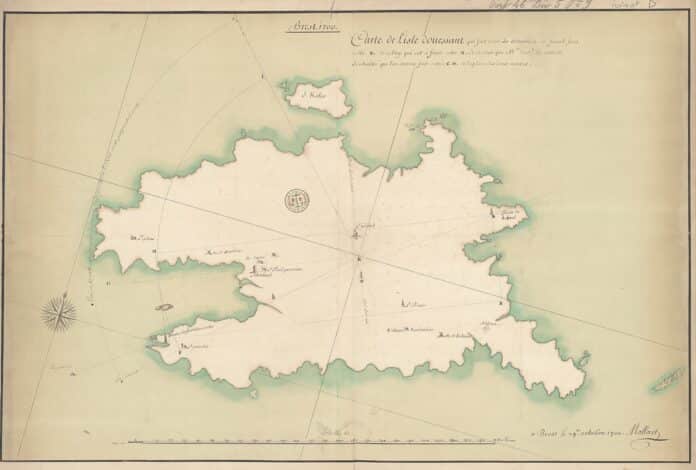

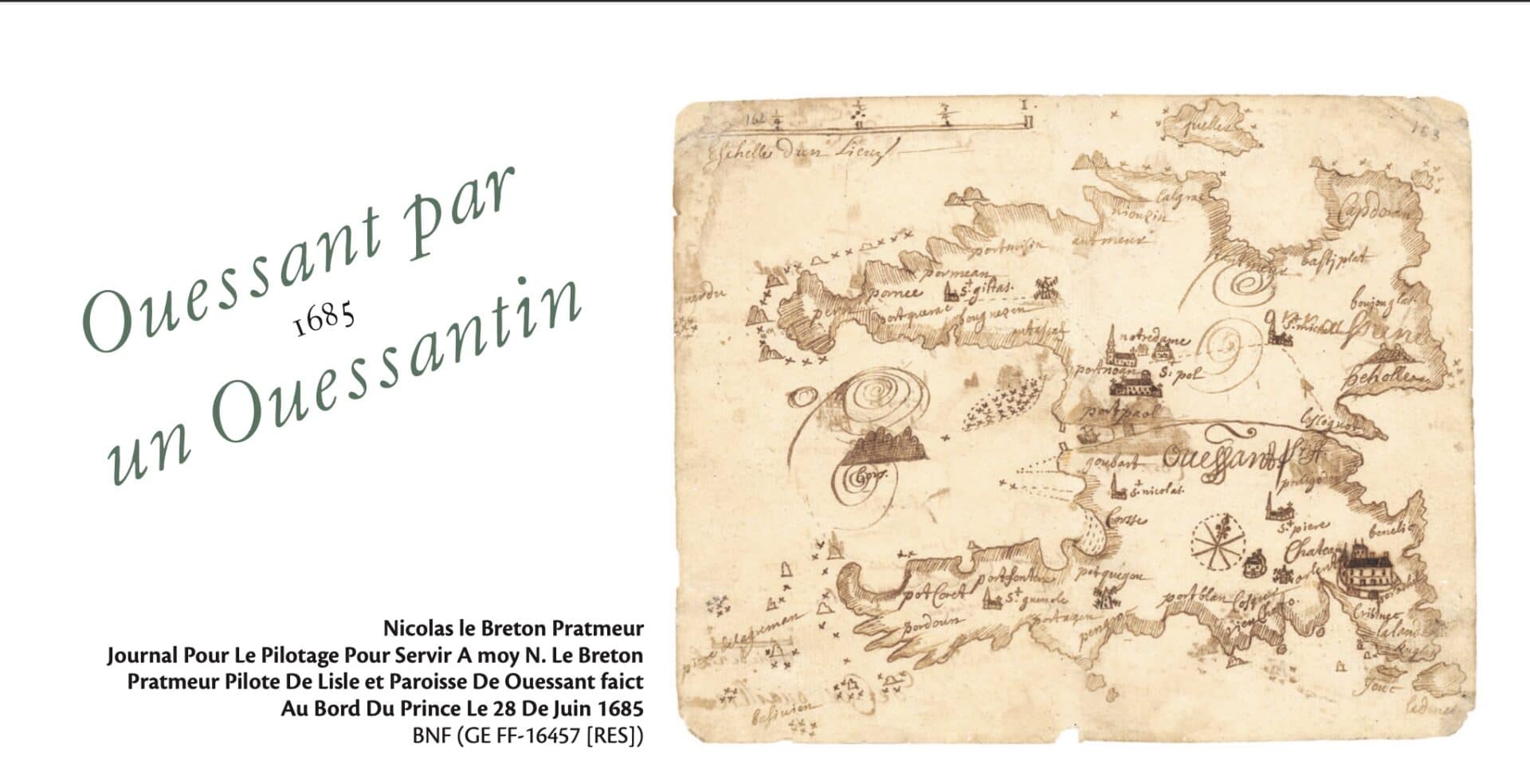

Ouessant mapped: from forgotten island to dream island

From Unidivers by Marjolaine Tanguy

A territory that maps bring back to life.

This is the promise kept by the exhibition L’île à la carte – Ouessant disparu, Ouessant imaginé (The island on the map – Ouessant lost, Ouessant imagined), on display until November 2, 2025, at the Stiff lighthouse.

Organized by the Ar(t) Stiff association and curated by cartographer Laurent Gontier, this geo-historical exploration brings to life a submerged past, between military memory, ghost landscapes, and engineers' utopias.

The magnificent catalog that accompanies it, published by Les Îliennes, is a scholarly and sensitive compendium of representations of Ouessant since the 17th century.

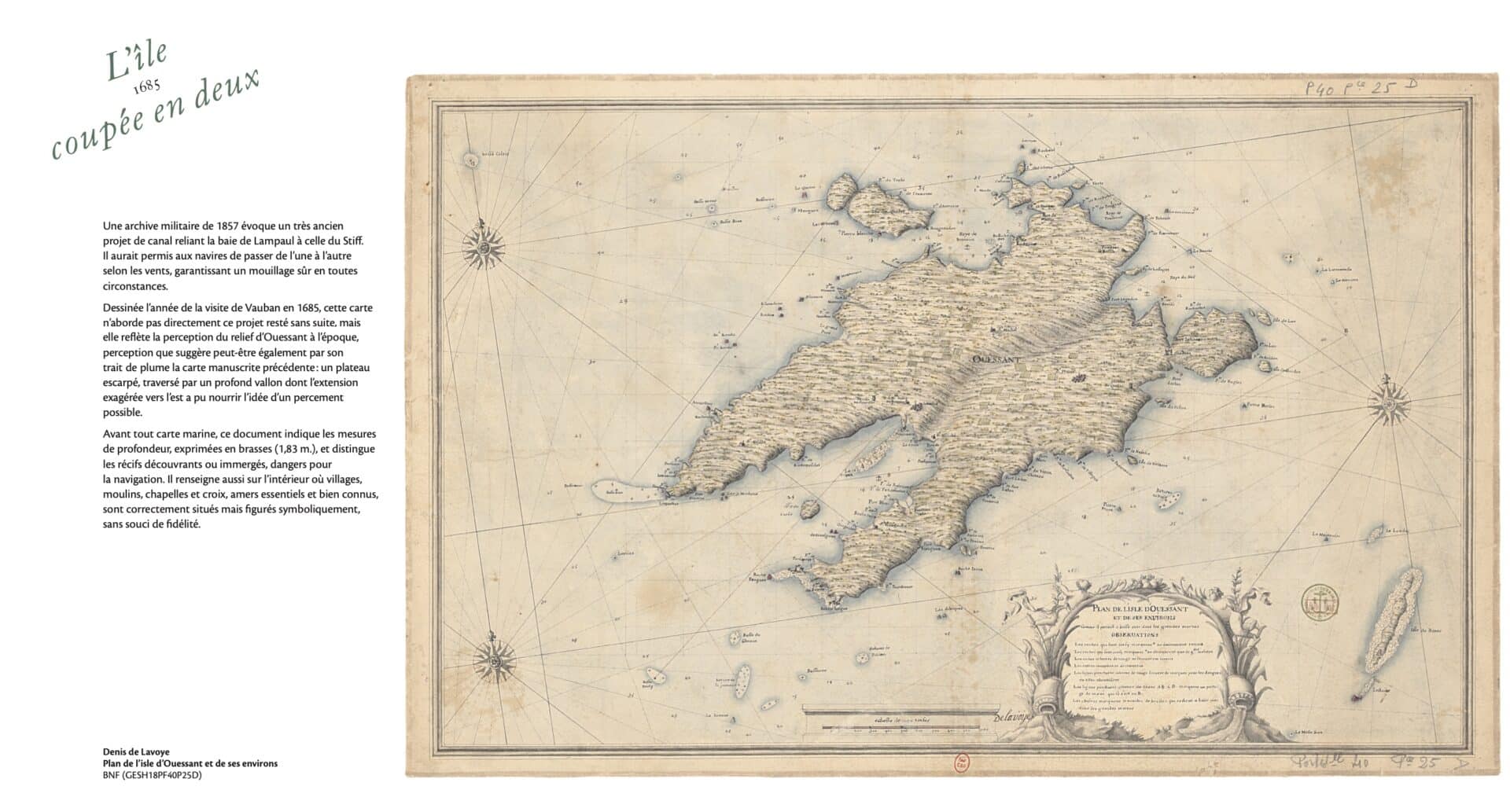

From the very first pages of the book, a strong intuition emerges: a map is never neutral.

It is the imprint of an era, a power, an intention.

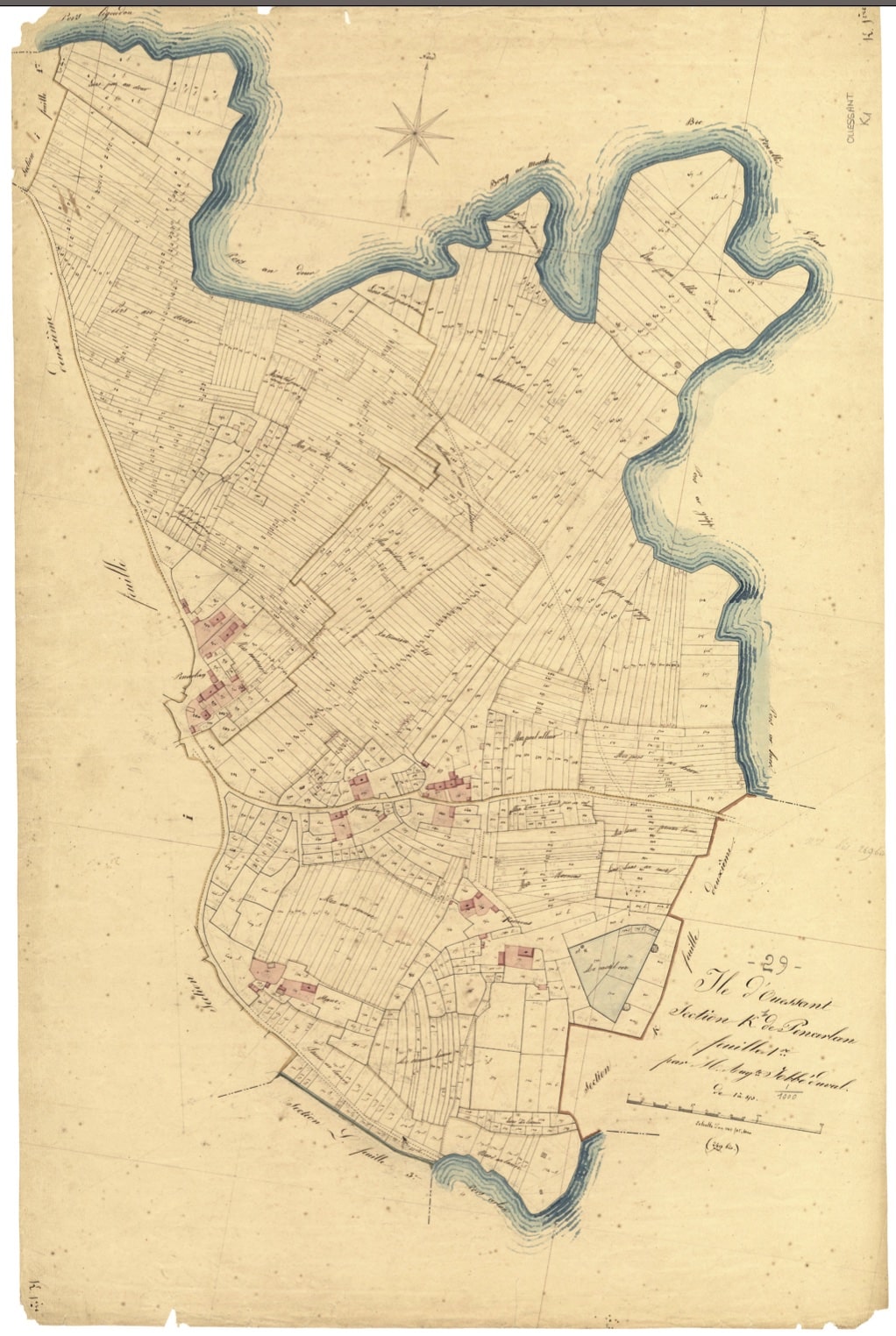

Through a rich selection of documents from the Defense Historical Service, the BnF, the SHOM, and departmental archives, the exhibition shows Ouessant as seen by military engineers, naval pilots, surveyors, and cadastral dreamers.

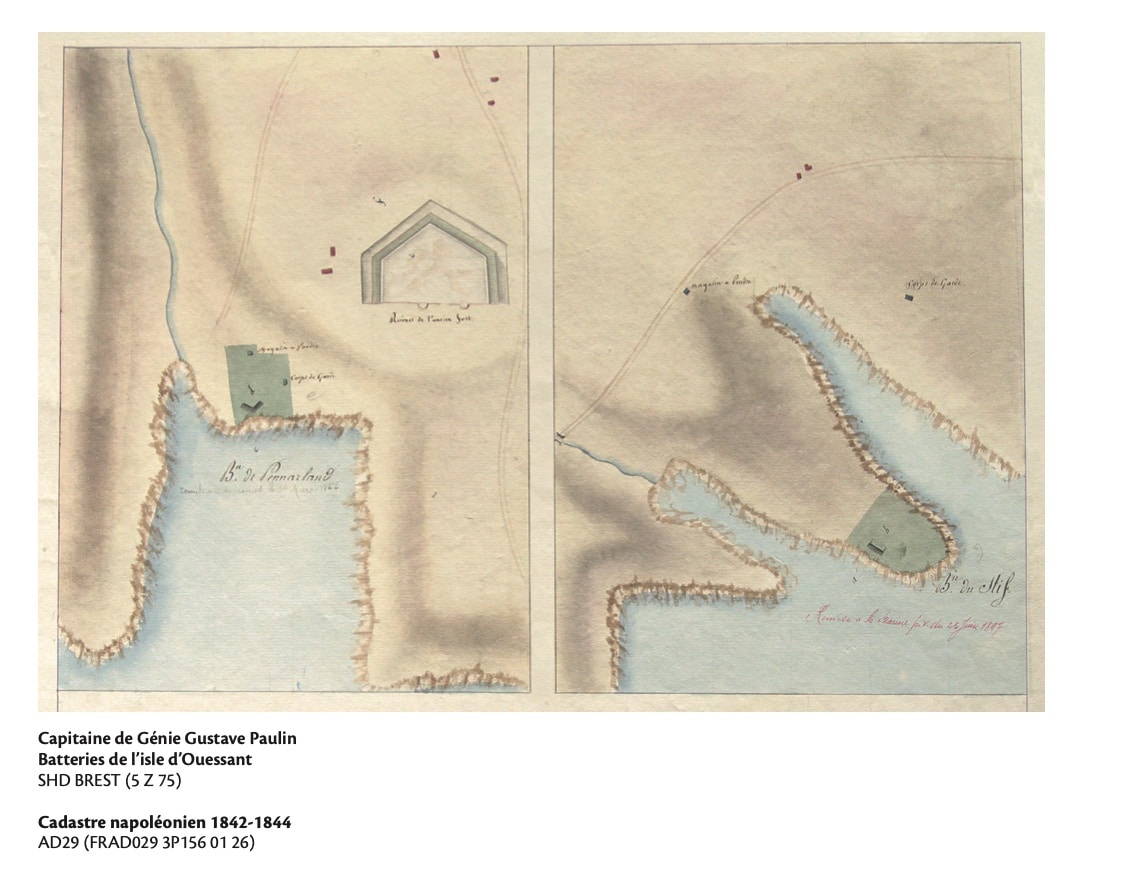

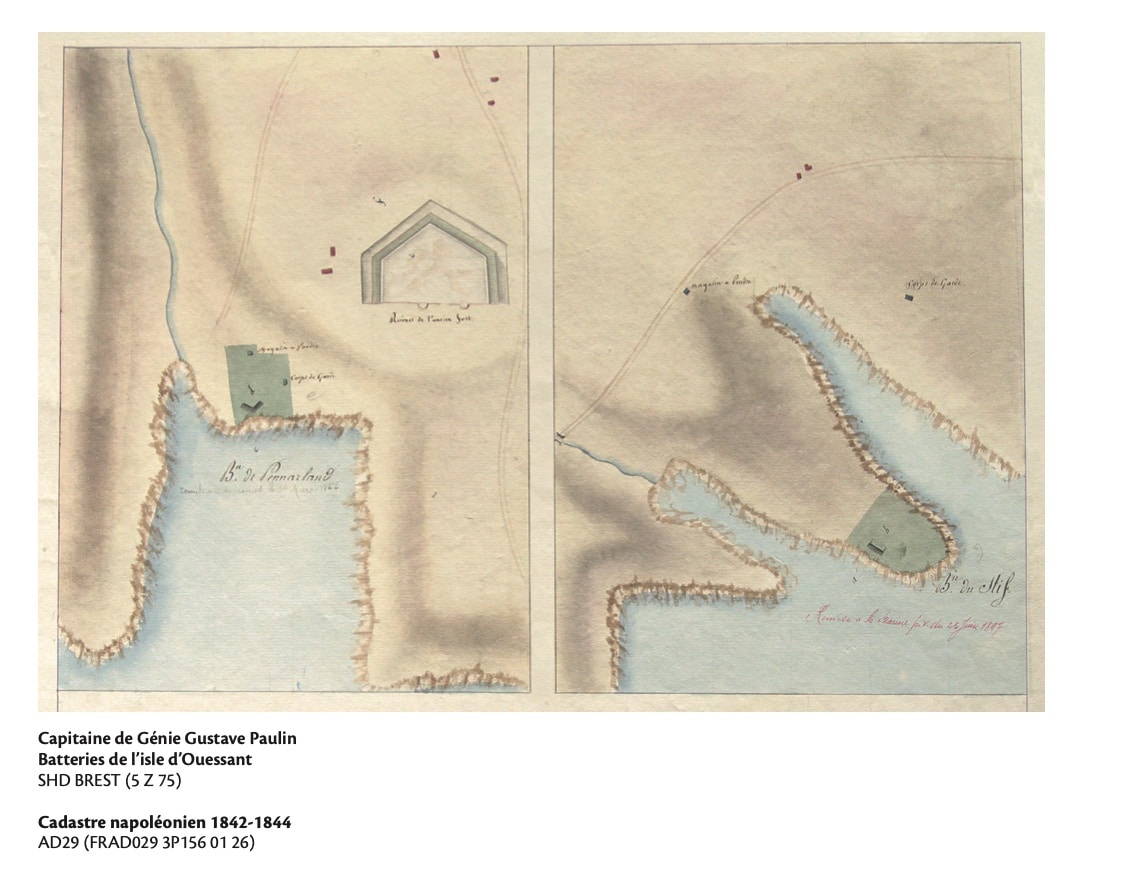

From Vauban's maps (1685) to the surveys of the Génie in the 19th century, another Ouessant emerges: a military island, strategic, defended, planned.

An island crisscrossed by coastal batteries, forts that were never built, abandoned dykes, and vanished chapels.

An island seen from above, but also traversed by the imagination.

This is the promise kept by the exhibition L’île à la carte – Ouessant disparu, Ouessant imaginé (The island on the map – Ouessant lost, Ouessant imagined), on display until November 2, 2025, at the Stiff lighthouse.

Organized by the Ar(t) Stiff association and curated by cartographer Laurent Gontier, this geo-historical exploration brings to life a submerged past, between military memory, ghost landscapes, and engineers' utopias.

The magnificent catalog that accompanies it, published by Les Îliennes, is a scholarly and sensitive compendium of representations of Ouessant since the 17th century.

From the very first pages of the book, a strong intuition emerges: a map is never neutral.

It is the imprint of an era, a power, an intention.

Through a rich selection of documents from the Defense Historical Service, the BnF, the SHOM, and departmental archives, the exhibition shows Ouessant as seen by military engineers, naval pilots, surveyors, and cadastral dreamers.

From Vauban's maps (1685) to the surveys of the Génie in the 19th century, another Ouessant emerges: a military island, strategic, defended, planned.

An island crisscrossed by coastal batteries, forts that were never built, abandoned dykes, and vanished chapels.

An island seen from above, but also traversed by the imagination.

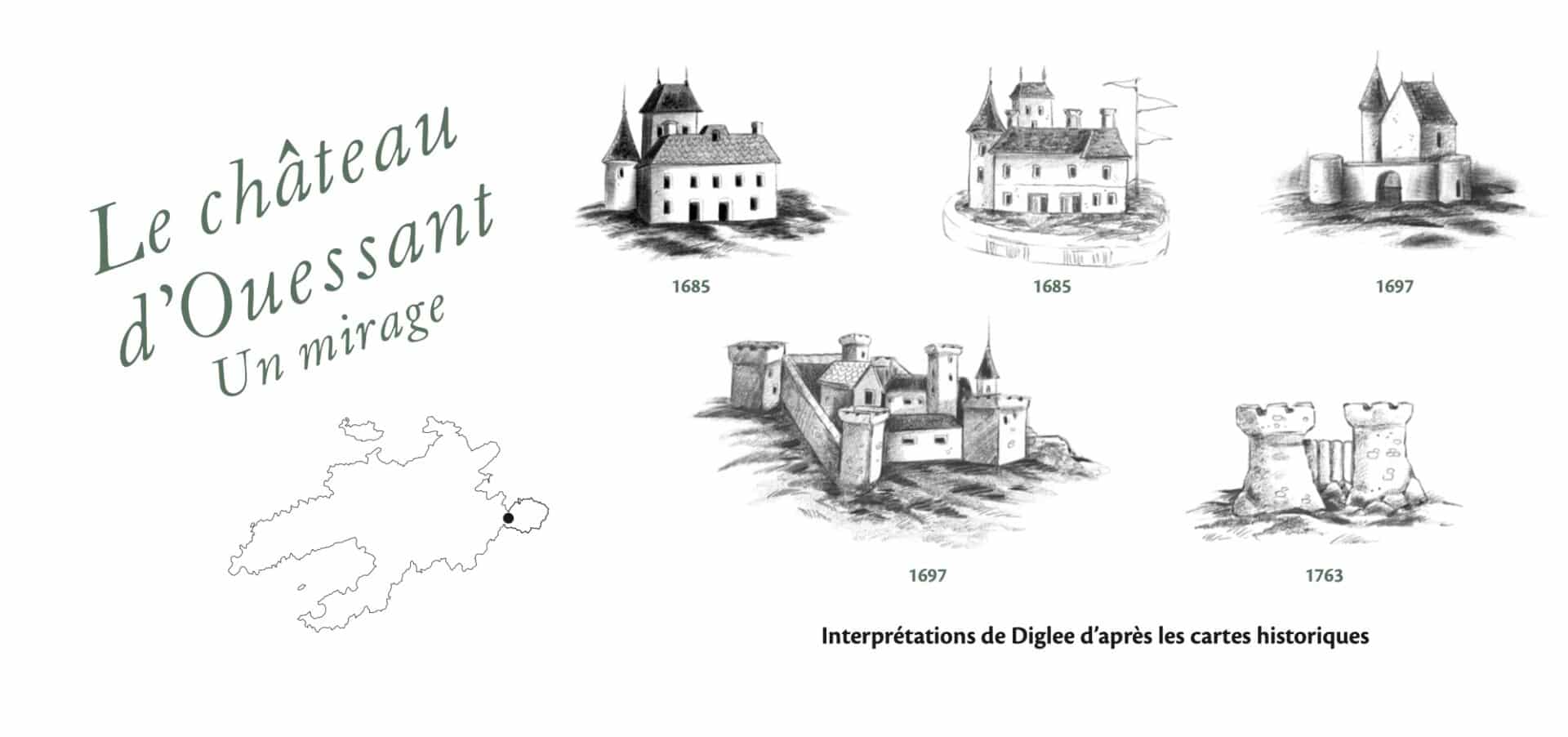

Laurent Gontier creates a dialogue between the maps to bring forth an alternative topography: that of forgotten intentions.

By revealing the successive layers of abandoned projects, he recreates a Ouessant that could have been.

This speculative reconstruction, both rigorous and poetic, culminates in 3D reconstructions of the Saint-Michel fort and the Créac'h lighthouse project.

The exhibition catalog is not just a simple annotated guide.

It is also the logbook of an investigation conducted over more than ten years by its author.

Gontier recounts his residencies on the island, his discoveries in the attics of the town hall, his dialogue with the inhabitants of Ouessant and schoolchildren, his comings and goings between the Napoleonic land registry and contemporary wastelands.

This interweaving of personal narrative, field research, and historical scholarship gives the project a rare depth.

It touches on geography as much as it does collective memory.

The island becomes a palimpsest, where traces of the past still surface in the landscape, in the names of plots of land, in a forgotten ruin.

At the heart of the project is an ethic of transmission: passing on to future generations what maps teach us—their graphic beauty, their technical rigor, their narrative power, but also their incompleteness—what they leave unsaid, what they leave to the reader's imagination.

The exhibition concludes with a contemporary section that questions what remains of these maps today: a collapsed wall in Kernoas, a cross on a vanished chapel, an incongruous relief at the bend in a path.

The map does not freeze space: it extends it.

It makes you want to walk, to search, to see differently.

It touches on geography as much as it does collective memory.

The island becomes a palimpsest, where traces of the past still surface in the landscape, in the names of plots of land, in a forgotten ruin.

At the heart of the project is an ethic of transmission: passing on to future generations what maps teach us—their graphic beauty, their technical rigor, their narrative power, but also their incompleteness—what they leave unsaid, what they leave to the reader's imagination.

The exhibition concludes with a contemporary section that questions what remains of these maps today: a collapsed wall in Kernoas, a cross on a vanished chapel, an incongruous relief at the bend in a path.

The map does not freeze space: it extends it.

It makes you want to walk, to search, to see differently.

"The attentive and knowledgeable eye can still spot the rare traces of the old batteries across the island.

The most spectacular remains are located at Kernoas, at the entrance to the Penn Arland peninsula.

Beneath the grass, the embankments and ditches designed to protect the cannons retain clearly marked contours, forming a triangle whose sides cover the enemy's possible approaches.

Its shape, clearly visible on the Napoleonic cadastre, is intriguing.

In particular, the two arcs to the east, which some believe to be the base of the towers of the old castle of Ouessant.

The most spectacular remains are located at Kernoas, at the entrance to the Penn Arland peninsula.

Beneath the grass, the embankments and ditches designed to protect the cannons retain clearly marked contours, forming a triangle whose sides cover the enemy's possible approaches.

Its shape, clearly visible on the Napoleonic cadastre, is intriguing.

In particular, the two arcs to the east, which some believe to be the base of the towers of the old castle of Ouessant.

Published in June 2025, the book-catalogue L’île à la carte – Ouessant disparu, Ouessant imaginé (ISBN 978-2-494215-04-7) is a work of art and knowledge.

Richly illustrated and featuring original cartography, it is a valuable tool for island history enthusiasts, researchers, teachers, and all lovers of Ouessant.

Richly illustrated and featuring original cartography, it is a valuable tool for island history enthusiasts, researchers, teachers, and all lovers of Ouessant.

Ouessant in the GeoGarage platform (SHOM nautical raster chart)

Thursday, August 7, 2025

The first 55-metre pointed-gear boat ever built is a sailing contemporary witness after an intensive refit

Gerda and Ebbe Andersen sailing off Marstal.

They spent three years working intensively on their boat designed by Aage Utzon.

They spent three years working intensively on their boat designed by Aage Utzon.

Photo: YACHT/Andreas Lindlahr

Before the Second World War, class pointed gates were a tribute to Danish workboats.

The "Undine" is a legendary boat of the scene and has now been restored.

The "Undine" is a legendary boat of the scene and has now been restored.

From Yacht by Andreas Fritsch

This was the case in 2016, when Marstal's best-known wooden boat builder, Ebbe Andersen, who had been restoring and building traditional wooden yachts and workboats for decades, returned with his wife Gerda from a trip to Sweden on their Colin Archer "Thor".

They stopped off in Helsingør on the Øresund and bumped into Bent Okholm Hansen on the jetty.

He is the owner of one of the rare and beautiful 55er pointed gates, of which only three were ever built.

The owner and the boat builder naturally get talking about the beautiful 55 at the jetty, and Okholm Hansen casually tells us that the second 55 still in existence in Denmark is on land not far from Gilleleje and has been slowly decaying under a tarpaulin for over a decade.

"I had heard about the ship as a young boatbuilder, and at the time there was talk of a very large pointed gate in Copenhagen.

But I never got to see it.

It was something of a legend, a masterpiece by the great designer Aage Utzon," says Ebbe, as everyone calls him.

"And as luck would have it, in the 1980s I had even written to the family of the now deceased designer for a customer of my shipyard and asked for a crack of his 55.

The customer was considering a replica.

I received a drawing, but nothing came of the new-build project." But the lines of the pointed gaff were already exceptionally appealing to him at the time.

"I knew straight away: that's it!"

The 55er Spitzgatter is, so to speak, the premier class in the development of the class Spitzgatter scene, which was further developed as touring and regatta boats built from the classic working boats of Danish fishermen.

They experienced their heyday from around the 1920s to the 1950s.

With a sail area of 55 square metres and a hull length of almost ten metres, the 55s were the largest boats of their time.

This is probably one of the reasons why only three boats were built.

Most pointed-gate class boats were significantly smaller.

And so it came as it had to.

"Gerda and I started to think about it.

In our mid-60s, we had come to the conclusion that at some point we would no longer be able to handle our 13-metre Colin Archer because of the rather heavy gaff rig.

So we were already looking for something more manageable so that we could continue sailing for as long as possible."

This gave rise to the idea of contacting the owner.

He turned out to be the boat builder who had bought the ship in poor condition in 2000 and had started to restore it, but simply hadn't found the time to make any progress.

Ebbe and Gerda travel to Gilleleje, but don't meet the owner there.

However, Ebbe discovers the boat in the yard under a tarpaulin.

"I knew straight away: that's it!" The owner had renewed the deck, refurbished the stern and built a new rudder.

"Good work!", Ebbe recognised.

And the owner didn't actually want to sell, but at some point he realised that there could hardly be a better opportunity to give "Undine" a second lease of life if the boat went to a well-known and renowned boat builder like Ebbe.

Three years, more than 2,000 hours of work

"I realised that it would be a lot of work, but I'm a professional, I knew exactly what we were getting into and what it would cost!" said Ebbe.

The only thing that mattered to him was that Gerda had to be involved.

It wouldn't work without his wife's blessing.

And he had already restored her Colin Archer "Thor" with her from 2010 to 2013.

Who knows whether she would be up for such an extensive refit again just three years later.

After all, they were both in their late 60s at the time, but he worried for nothing: she had fallen in love with the battered beauty just as much as he had.

And so "Undine", the first 55-metre spitsail ever built, is lorried to Marstal on the island of Ærø.

The inventory showed the route for the next few years: "The wooden part of the keel was cracked and had to be rebuilt.

That was the biggest construction site.

But the oak frames were all solid.

Some of the pine planks had to be stripped, and the hull had to be completely stripped of old paint and re-caulked," says Ebbe.

But the substance was otherwise good, the Oregon pine rig only needed eight new coats of paint, as did the mahogany interior.

The two show pictures of the refit: Gerda with a hot air gun stripping paint, Ebbe calendering, the construction of the new keel.

"We spent three years and more than 2,000 hours working on the boat," say Ebbe and Gerda over coffee and cinnamon buns, talking about the intricately detailed plans.

After the many anecdotes about the restoration, it's finally time for the boat.

So down to the jetty of the Marstal Sailing Club, less than 50 metres from Ebbe's old shipyard in the red and white wooden shed.

Ebbe sees the ship as a contemporary witness, it should be kept as original as possible and later passed on to the next generation.

The imposing mast of the 55 stands out: 18 metres on a wooden boat almost 10 metres long, filigree jumpstays in the top, backstays.

And then those hull lines.

The deck is beautifully shaped, narrow and elegant, the flat cabin superstructure nestles beautifully into the lines.

The slender hull merges into Utzon's trademark at the bow, a very voluminous, strongly rounded stem.

"It's really very wide," smiles Ebbe when I look at it, "a massive 25 centimetre wide piece of wood! Quite typical for Utzon!"

He turned out to be the boat builder who had bought the ship in poor condition in 2000 and had started to restore it, but simply hadn't found the time to make any progress.

Ebbe and Gerda travel to Gilleleje, but don't meet the owner there.

However, Ebbe discovers the boat in the yard under a tarpaulin.

"I knew straight away: that's it!" The owner had renewed the deck, refurbished the stern and built a new rudder.

"Good work!", Ebbe recognised.

And the owner didn't actually want to sell, but at some point he realised that there could hardly be a better opportunity to give "Undine" a second lease of life if the boat went to a well-known and renowned boat builder like Ebbe.

Three years, more than 2,000 hours of work

"I realised that it would be a lot of work, but I'm a professional, I knew exactly what we were getting into and what it would cost!" said Ebbe.

The only thing that mattered to him was that Gerda had to be involved.

It wouldn't work without his wife's blessing.

And he had already restored her Colin Archer "Thor" with her from 2010 to 2013.

Who knows whether she would be up for such an extensive refit again just three years later.

After all, they were both in their late 60s at the time, but he worried for nothing: she had fallen in love with the battered beauty just as much as he had.

And so "Undine", the first 55-metre spitsail ever built, is lorried to Marstal on the island of Ærø.

The inventory showed the route for the next few years: "The wooden part of the keel was cracked and had to be rebuilt.

That was the biggest construction site.

But the oak frames were all solid.

Some of the pine planks had to be stripped, and the hull had to be completely stripped of old paint and re-caulked," says Ebbe.

But the substance was otherwise good, the Oregon pine rig only needed eight new coats of paint, as did the mahogany interior.

The two show pictures of the refit: Gerda with a hot air gun stripping paint, Ebbe calendering, the construction of the new keel.

"We spent three years and more than 2,000 hours working on the boat," say Ebbe and Gerda over coffee and cinnamon buns, talking about the intricately detailed plans.

After the many anecdotes about the restoration, it's finally time for the boat.

So down to the jetty of the Marstal Sailing Club, less than 50 metres from Ebbe's old shipyard in the red and white wooden shed.

Ebbe sees the ship as a contemporary witness, it should be kept as original as possible and later passed on to the next generation.

The imposing mast of the 55 stands out: 18 metres on a wooden boat almost 10 metres long, filigree jumpstays in the top, backstays.

And then those hull lines.

The deck is beautifully shaped, narrow and elegant, the flat cabin superstructure nestles beautifully into the lines.

The slender hull merges into Utzon's trademark at the bow, a very voluminous, strongly rounded stem.

"It's really very wide," smiles Ebbe when I look at it, "a massive 25 centimetre wide piece of wood! Quite typical for Utzon!"

The massive bow, which is en vogue again today, provides more volume in the foredeck and should allow the boat to move smoothly through the waves.

In fact, the pointed gates from his pen are known for their excellent seaworthiness in the often short and rough Baltic Sea waves.

Utzon's pupil Peter Bruun continued the idea later in the 1970s in the popular GRP pointed gates Spækhugger and Grinde.

In fact, the pointed gates from his pen are known for their excellent seaworthiness in the often short and rough Baltic Sea waves.

Utzon's pupil Peter Bruun continued the idea later in the 1970s in the popular GRP pointed gates Spækhugger and Grinde.

Slim lines, powerful bow - the trademark of Utzon designs.

"Undine" is kept as original as possible

And then, of course, the beautiful, gently rounded stern.

It looks elegant and graceful, as is usual with pointed gates, a boat that is as beautiful at the back as it is at the front.

The hull is white, the plywood deck and pine cabin roof in the lime green of the Marstal schooners and workboats, to which Ebbe is deeply connected through many new builds and above all the renovation of the schooner "Bonavista".

What is striking, however, is that "Undine" is in no way modernised for the ship of a married couple in the 70s: Furling foresail, sea fence, bow or stern pulpit, deflected halyards - not a thing.

That would never occur to Ebbe: "It was important to us to keep the boat as original as possible," he says when asked about this.

It should remain a kind of sailing contemporary witness.

Paradoxically, it was precisely for this reason that the Andersens decided to make a radical change to the pointed batten during the restoration: "The boat was built in 1936 at the Lilleø shipyard for a Copenhagen watchmaker.

Although the drawing for the cabin superstructure by Aage Utzon included windows, the owner left them out and only a skylight in the deck provided light.

We don't know why," says Ebbe.

"That's the fascinating thing about wooden boats: 'Undine' has been sailing for 80 years.

And once we're gone, she'll be able to do it again."

Perhaps his privacy was important to him.

In any case, the first owner was an original character.

He was known for sailing through the Danish archipelago on his holidays and asking the locals in every harbour if anyone had a watch to repair.

If they did, he asked them to take it with them and bring it back repaired on their next visit by boat.

In any case, Ebbe put the saw to work and cut out the windows afterwards.

Old-school sailors

But now it's time to go sailing off the coast of Marstal.

Wind force three is blowing outside.

The owner couple decide in favour of the working jib, as the boat has plenty of sail area.

The boom extends well up to the centre of the cockpit - and used to be significantly longer.

"The original boom practically went all the way to the stern, but the last owner shortened it a little.

The rudder pressure was too great for him.

As a result, the sail is four square metres smaller."

As was customary in the past, the main halyard is operated directly on the mast, while the small mast cockpit around the base of the mast allows for good stability.

The sails fill up, "Undine" leans to one side and sets off unperturbed despite the small working jib.

The ship lies comfortably on the attached rudder, helped by the long tiller.

The cockpit is deep and the crew is very well protected.

What is striking is that there are no forecastle boxes under the cockpit thwarts.

Ebbe explains why: "Topgates are sensitive to trim due to the low buoyancy in the stern area.

Even when the cockpit is full, the stern dips deeply.

Utzon didn't draw any in the first place so that the owners don't exacerbate this by overfilling the cockpit."

The deck of "Undine" has clear lines, is very uncluttered and comfort such as a sprayhood is out of the question for the Andersens.

They are old-school sailors, even if they "only" sail for a maximum of six to ten hours at a time, as Ebbe notes.

Meanwhile, his enormously strong hands, which bear impressive witness to a life as a boat builder, grip the tiller almost tenderly.

You can feel that "Undine" and he are a perfect match.

You could do endless laps in the glorious sunshine off Marstal, the 55 elegantly lapping its course.

Temporary custodian of a cultural asset

What is surprising is the saloon: it ends directly in front of the mast, with a bulkhead in front of the pipe separating it from the foredeck.

If you want to get to the berths there, you have to go below deck via a second companionway in front of the rigging.

Unconventional, but also consistent, as Ebbe finds.

Structurally, of course, this has many advantages, and it is not easy to pass the mast on the left and right anyway.

Stowed wet sails or equipment were also spatially separated from the saloon.

A simple galley with a two-burner spirit cooker, a spartan wet room on the starboard side with a small wash basin and toilet, some cupboard space and room for the nautical chart - that's it.

The only recognisable concession to modernity is an iPad holder with power supply; there is no plotter.

A simple, aesthetically unpretentious ship, no matter where you look.

A sailing piece of contemporary history.

The owner couple happily sails their "Undine" in Danish waters on their doorstep.

Should this no longer be possible at some point, they hope to find a successor who appreciates what they have created through the restoration: "'Undine' had already sailed for 80 years before we took her over and can continue to sail in exactly the same way for another 80, long after the two of us are no longer around.

That's the fascinating thing about old wooden boats!" says Ebbe.

The owner as the temporary custodian of a cultural asset.

It's great that there are still people like that around today.

Links :

Wednesday, August 6, 2025

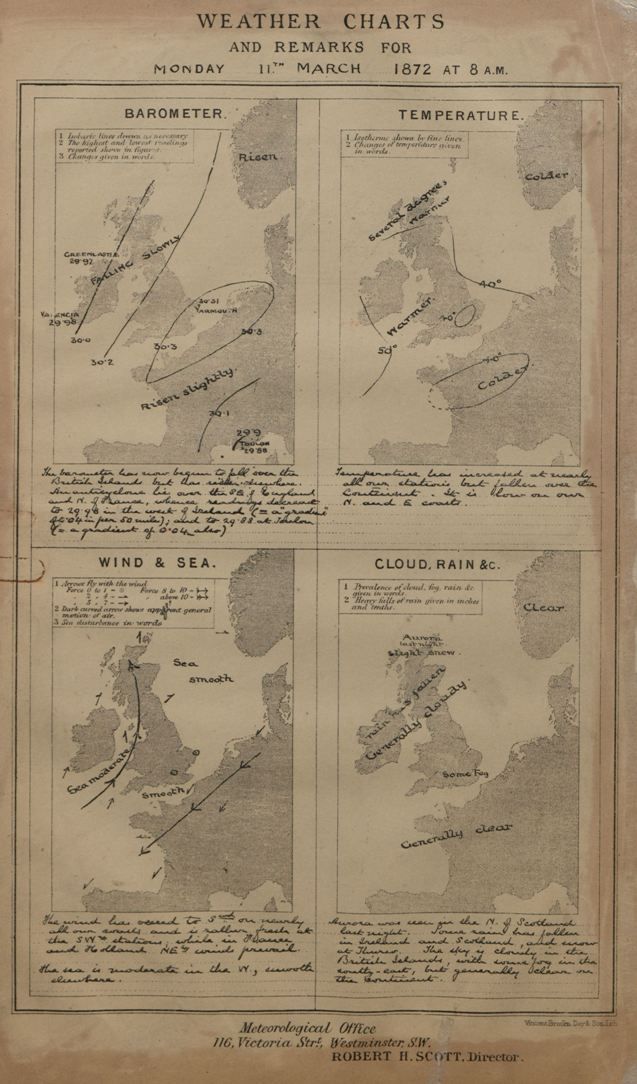

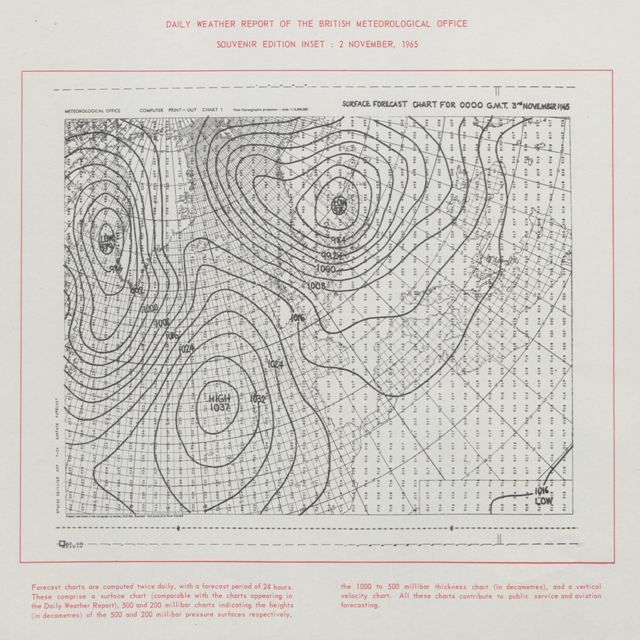

World’s first weather forecast published

From History

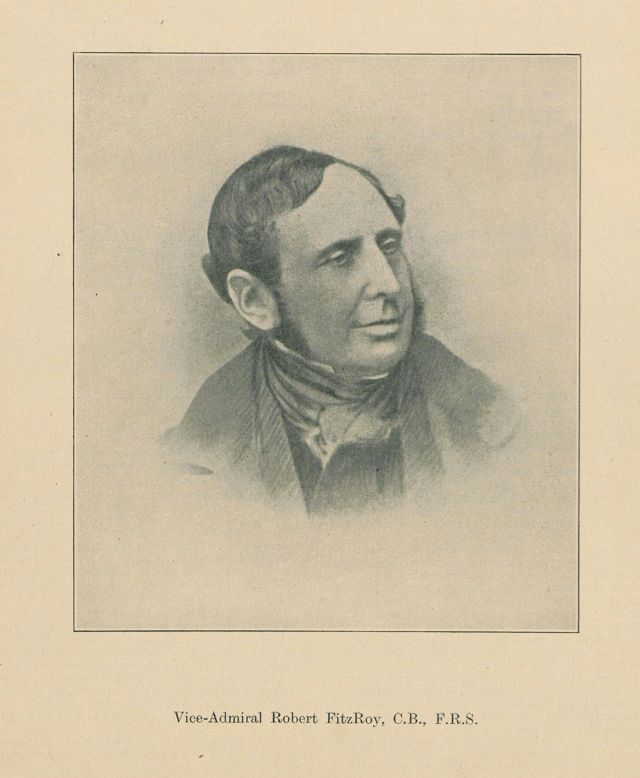

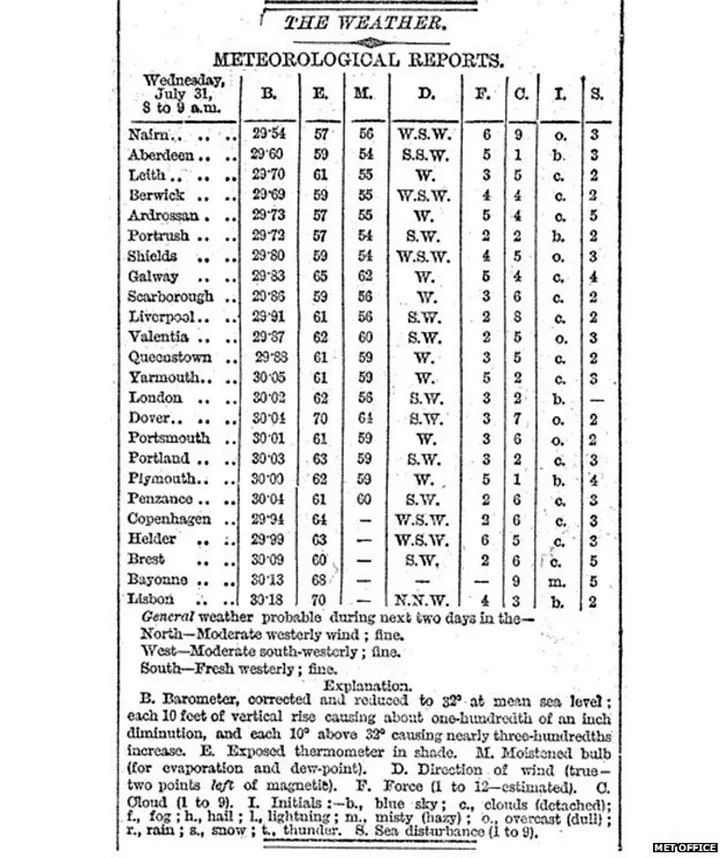

On August 1, 1861, Robert FitzRoy, a British naval officer who had been researching ways to predict the weather, publishes the first known weather forecast in The Times.

The report, which includes a prediction of 62 degrees and clear skies in London, is largely accurate.

Fitzroy—who had captained the famed HMS Beagle, which sailed around the world with naturalist Charles Darwin—had become concerned about the massive loss of life at sea, with more than 7,400 shipwrecks near the British coast over a five-year period.

The first Weather Forecast published in The Times. Source: Met Office

Fitzroy believed advance warning about rough weather could prevent many such tragedies.

Why Hurricanes Have Names

At first, hurricanes were only given women's names -- until some women protested and got storms named after men, too.

In a world before forecasts, people relied on simply watching clouds or even observing animal behavior to predict storms.

Why Hurricanes Have Names

At first, hurricanes were only given women's names -- until some women protested and got storms named after men, too.

In a world before forecasts, people relied on simply watching clouds or even observing animal behavior to predict storms.

When “weather frogs” climbed up a little ladder in a jar with water, for example, it supposedly predicted good weather; if the frog climbed down, people believed rain was coming.

In 1854, FitzRoy, by then a vice-admiral, established the Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade.

In 1854, FitzRoy, by then a vice-admiral, established the Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade.

The organization, later called the Met Office, initially produced wind charts intended to help boats reduce their sailing times.

In 1859, the British government gave FitzRoy the authority to start issuing storm warnings, which he did using the electric telegraph, a new technology.

He started sending his predictions to newspapers.

This is a celebratory film to mark 170 years of the Met Office.

Beginning in 1854, when Captain Robert Fitzroy founded the Meteorological Department, we share some of the key dates in our history of innovation and public service.

From the first storm warning system in 1861, to advancing weather and climate science and services around the world today.

After the initial August 1 forecast, weather reports quickly became very popular and syndicated in publications around England.

It wasn’t just fishermen and sailors, traditionally affected by the weather, who availed themselves of the forecasts.

People involved in organizing events like county fairs and flower shows obsessively followed them as well.

Some people even used the forecasts for more speculative purposes, like picking which horse to bet on in races, depending on how the weather might affect track turf.

Links :

- BBC : The birth of the weather forecast

- MetOffice : Robert FitzRoy and the early Met Office

- MetOffice : Our history

- Reading Univ : UK Met Office founder’s 19th century weather data rescued

Tuesday, August 5, 2025

“Blue Homeland” from Libya to the Mediterranean: Libya submits map of outer continental shelf boundaries up to Crete – Urges Athens and Cairo to cancel exploration and licensing rounds

On May 27, Libya submitted a Note Verbale to the UN—published as an official document on July 1—attempting to impose faits accomplis based on the Turkey-Libya Memorandum of Understanding, primarily against Greece, but also Egypt

Under Turkey’s full guidance and drawing on arguments from the Turkish Foreign Ministry, Libya submitted coordinates and a map defining the outer boundaries of its continental shelf, seeking to secure the “benefits” granted by the Turkish-Libyan MoU at the expense of Greek and Egyptian maritime rights.

This action mirrors Turkey’s own 2020 move, when it unilaterally submitted continental shelf boundaries to the UN based on the same MoU, disregarding Greece’s and Cyprus’s rights in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Libya now declares illegal the Greece-Egypt Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) agreement, Greece’s EEZ declaration in the Ionian Sea, and its Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) framework, attempting a broad challenge to Greek maritime zones, even in regions like the Ionian Sea and south of Crete—where Turkey has no geographical basis to intervene.

Like Turkey, Libya argues that the median line should be drawn between continental coasts only, and that islands do not automatically generate full maritime zones, claiming they should either be ignored or given reduced effect in boundary delimitation, based on the circumstances.

In the Note Verbale, Libya declares:

Like Turkey, Libya argues that the median line should be drawn between continental coasts only, and that islands do not automatically generate full maritime zones, claiming they should either be ignored or given reduced effect in boundary delimitation, based on the circumstances.

In the Note Verbale, Libya declares:

- The Greece-Egypt EEZ agreement is illegal and infringes on Libya’s continental shelf.

- The Greek EEZ declaration in the Ionian, published in the Government Gazette on April 18, 2025, is also illegal and violates both Libya’s continental shelf and fundamental principles of the Law of the Sea.

- It fully rejects what it calls the “illegal and maximalist” claims of Greece and Egypt over maritime borders, as well as their offshore licensing rounds.

- Moreover, Libya states that any boundary delimitation must:Respect Libyan national law (e.g., closing the Gulf of Sirte and ignoring islands).

- Be based on the Turkey-Libya MoU.

- Occur through negotiation under Article 33 of the UN Charter, including possible referral to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

It also denounces hydrocarbon exploration activities by foreign companies in Greek blocks southeast and south of Crete, and similar Egyptian actions, calling on both countries to cease all exploration and licensing until disputes are resolved.

By unilaterally submitting its continental shelf boundaries, Libya opens a new diplomatic front for Greece, jointly with Turkey attempting to box Greece into narrow maritime zones barely extending beyond its 6-nautical-mile territorial waters.

Libya’s formal stance—that dialogue must include recognition of the Turkey-Libya MoU—limits prospects for productive negotiations.

By unilaterally submitting its continental shelf boundaries, Libya opens a new diplomatic front for Greece, jointly with Turkey attempting to box Greece into narrow maritime zones barely extending beyond its 6-nautical-mile territorial waters.

Libya’s formal stance—that dialogue must include recognition of the Turkey-Libya MoU—limits prospects for productive negotiations.

EEZ in the GeoGarage platform

At the same time, it highlights the critical need for close Greek-Egyptian cooperation, as Egypt also comes under fire from Libya, albeit over a much smaller maritime area than Greece.

Following meetings held by Greek Foreign Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis with both Libyan factions, it is clear that the situation has entered a new phase, although maintaining communication channels with both Tripoli and Benghazi remains crucial.

The Libyan Note Verbale includes coordinates and a map of Libya’s claimed “outer limits” of the continental shelf, asserting:

Following meetings held by Greek Foreign Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis with both Libyan factions, it is clear that the situation has entered a new phase, although maintaining communication channels with both Tripoli and Benghazi remains crucial.

The Libyan Note Verbale includes coordinates and a map of Libya’s claimed “outer limits” of the continental shelf, asserting:

The Turkey-Libya MoU, signed in November 2019 and registered with the UN, defines the maritime boundary between the two states.

According to Libya, Greece and Egypt have no sovereign rights in the areas demarcated by the MoU.

Libya rejects the 2020 Greece-Egypt EEZ agreement as invalid, claiming it violates international law and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Libya rejects the 2020 Greece-Egypt EEZ agreement as invalid, claiming it violates international law and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Libya condemns Greece’s hydrocarbon exploration, including:

- Offshore permits since November 26, 2022

- New surveys approved in April 2024

- The Greek MSP plan announced on April 16, 2025, which, according to Libya, violates its sovereign rights in areas it claims jurisdiction.

Libya disputes Greece’s April 2025 Ionian EEZ declaration, calling it illegal since it allegedly extends into Libyan continental shelf areas.

Libya claims that the median line must be drawn between mainland coasts, asserting that Greek islands should not generate full maritime zones if they distort equitable delimitation.

The document details coordinates from east to west, based on the Turkey-Libya MoU and various ICJ rulings (Libya-Malta 1985, Libya-Tunisia 1982), asserting historic rights in the Gulf of Sirte and beyond.

Finally, Libya states it reserves all legal rights under international law over its seabed, subsoil, and overlying waters, and calls for:

Libya claims that the median line must be drawn between mainland coasts, asserting that Greek islands should not generate full maritime zones if they distort equitable delimitation.

The document details coordinates from east to west, based on the Turkey-Libya MoU and various ICJ rulings (Libya-Malta 1985, Libya-Tunisia 1982), asserting historic rights in the Gulf of Sirte and beyond.

Finally, Libya states it reserves all legal rights under international law over its seabed, subsoil, and overlying waters, and calls for:

- Negotiations with all coastal neighbors

- Suspension of all exploration and licensing by Greece and Egypt

- A resolution based on valid international agreements

Links :

Monday, August 4, 2025

Mapping the deep: Marie Tharp’s physiographic diagram of the Atlantic Ocean

Manuscript painting of Heezen-Tharp’s “World Ocean Floor” map.

Heinrich C. Berann, 1977.

Geography and Map Division.

Heinrich C. Berann, 1977.

Geography and Map Division.

From LOC by Julie Stoner

This is a guest post by Colette Harley, a Junior Fellow in the Geography and Map Division.

My Junior Fellowship project this summer was entitled “Marie Tharp, Mapmaking Pioneer – Diving into Unprocessed Collection Material”.

As an archivist, my ears always perk up at the phrase “unprocessed material.” This is a bit of a catch-all term for materials that aren’t ready for researchers just yet.

Often, they are unsorted and under-described, which makes their usefulness for researchers limited.

I was also drawn to the work of Marie Tharp, an oceanographer and geologist, who created the first map of the Atlantic Ocean Floor in 1957.

Tharp’s collection is large and documents her career working at the Lamont Geological Observatory and her personal life, as well as the professional and personal papers of her long-time collaborator, Bruce C.

Heezen.

My task was to create an inventory of some of the oversized materials housed in flat files in the G&M stacks.

Much of the material was related to the process of map making – reference maps, graphs, earthquake and seismicity information, negatives of bathymetry and contour data, as well as ship course data.

The material ranged from plastic sheets to a specific copying process called Ozalid, which was used during this time for engineering diagrams and is akin to a white print.

I relied heavily on documentation created by Gary North, the original processor of the collection.

This documentation helped me to understand what these different data sheets were and how Tharp might have used them in her mapmaking.

The running count of the inventory is over 1,300 items, and this will be added to the collection so researchers can access these materials.

My Junior Fellowship project this summer was entitled “Marie Tharp, Mapmaking Pioneer – Diving into Unprocessed Collection Material”.

As an archivist, my ears always perk up at the phrase “unprocessed material.” This is a bit of a catch-all term for materials that aren’t ready for researchers just yet.

Often, they are unsorted and under-described, which makes their usefulness for researchers limited.

I was also drawn to the work of Marie Tharp, an oceanographer and geologist, who created the first map of the Atlantic Ocean Floor in 1957.

Tharp’s collection is large and documents her career working at the Lamont Geological Observatory and her personal life, as well as the professional and personal papers of her long-time collaborator, Bruce C.

Heezen.

My task was to create an inventory of some of the oversized materials housed in flat files in the G&M stacks.

Much of the material was related to the process of map making – reference maps, graphs, earthquake and seismicity information, negatives of bathymetry and contour data, as well as ship course data.

The material ranged from plastic sheets to a specific copying process called Ozalid, which was used during this time for engineering diagrams and is akin to a white print.

I relied heavily on documentation created by Gary North, the original processor of the collection.

This documentation helped me to understand what these different data sheets were and how Tharp might have used them in her mapmaking.

The running count of the inventory is over 1,300 items, and this will be added to the collection so researchers can access these materials.

A.K.

Lobeck, 1948.

Lobeck, 1948.

Geography and Map Division.

Heezen and Tharp’s first published map was a physiographic diagram of the Atlantic Ocean floor, published in 1957.

Physiographic diagrams were first popularized by Armin K.

Lobeck and Erwin Raisz, and depict geological features as if looking at them from above and slightly sideways.

I was interested in these maps for their aesthetic appeal and uniqueness – I had never seen this type of map before.

Although their uses in actual wayfinding may be limited, these maps convey an overarching image of the place they depict almost instantaneously.

In thinking about maps, there is often a connection between form and function.

How a map maker depicts data on the map is often tied to its uses: a tourist map may have additional information about where to get a meal and precise locations are not as paramount.

When working with a nautical chart or topographic map where precise data or use is required, the map maker can choose the type of map best suited to that data and purpose.

Heezen and Tharp’s reasoning for picking this specific type of map is a confluence of history and practicality.

Physiographic Diagram of the Atlantic Ocean, Sheet 1.

Physiographic Diagram of the Atlantic Ocean, Sheet 1.Bruce C.

Heezen and Marie Tharp, 1957.

Geography and Map Division.

A primary reason for choosing a physiographic diagram versus a straight topographical map was the consideration of the Cold War.

Much of the data Heezen and Tharp utilized was considered classified and so the physiographic diagram was a way to depict the ocean floor without revealing the data they had used.

Additionally, data of the ocean floor was incomplete.

Research vessels often traveled in straight lines and did not acquire data for every square inch of ocean floor.

Thus, as Tharp completed the map, she relied on her training as a geologist to make educated guesses and fill in the missing data to complete the ridges.

Tharp and Heezen note the difficulty of mapping an un-seeable area in their book, The Floors of the Oceans: I.

The North Atlantic:

“There is a fundamental difference between the preparation of a terrestrial and a marine physiographic diagram… Except in unexplored, inaccessible areas, the shape of all land feature is a matter of recorded fact; the problem is to abstract and artfully draw the features in question.

In contrast, preparation of a marine physiographic diagram requires the author to postulate the patterns and trends of the relief on the basis of cross sections and then to portray this interpretation in the diagram.”

Much of this map relies on intuition, which without Tharp’s training as a geologist would have been very difficult.

Draft of a physiographic diagram.

Draft of a physiographic diagram.Marie Tharp, undated.

Geography and Map Division.

A final reason for choosing this type of map was its ease of conveying data.

Viewers could look at the map, whether they were scientists, school children, or members of the public and understand the ridges and valleys that populated the ocean floor.

Prior to this map our understanding of what lay beneath the ocean was minimal.

This map depicts the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean as a complex and varied place, not just flat sand for thousands of miles.

It also outlined the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a deep valley and mountain range that separates the North American plate from the Eurasian plate.

While creating this map, Tharp and Heezen overlaid seismicity and earthquake data on the map and realized that many of the earthquakes occurred along this ridge.

This map was a huge step forward in the acceptance of plate tectonics and continental drift, a controversial idea first proposed by Alfred Wegner in 1912.

Tharp and Heezen went on to create maps of much of the ocean floor, without computers or automation, and published several physiographic diagrams of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.

They worked closely together until Heezen’s death in 1977 shortly after they had completed their first map of the ocean floor with artist Heinrich C.

Berann.

It was a pleasure to spend so much time with Tharp’s work and to learn from everyone in the Geography and Map Division this summer.

Links :

- View other blog posts and story maps from the LOC on Marie Tharp and mapping the ocean floor.

- Read Hali Felt’s biography of Marie Tharp, Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor.

- Explore the Heezen-Tharp Collection finding aids.

- GeoGarage blog : Geologist Marie Tharp mapped the ocean floor and helped / How pioneering geologist Marie Tharp changed our view of Earth / Marie Tharp's adventures in mapping the seafloor, in her ... / Marie Tharp: the woman who mapped the ocean floor / How one brilliant woman mapped the ocean floor's secrets / The great challenge of mapping the sea / The floor of the ocean comes into better focus

Sunday, August 3, 2025

Teahupo'o, July 28, 2025

A very special day at the end of the road. Matahi Drollet on quite possibly one of the most heavy and technical waves ever ridden anywhere ever...

There were plenty more incredible waves tackled that morning so sit back and enjoy the ride...

Surfers:

- Tereva David

- Eimeo Czermack

- Mateia Hiquily

- Gilbert Teave

- Peio Ostolozaga

- Italo Ferreira

- Manake'i Keikahiha

- And of course, Matahi Drollet

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)