Saturday, May 13, 2023

Denmark's $34BN energy islands could solve Europe's power problem ?

Friday, May 12, 2023

NOAA, Proteus Ocean Group to explore uses of groundbreaking underwater lab

NOAA and Proteus Ocean Groupoffsite link have signed a formal agreement to use the “underwater space station of the ocean,” PROTEUS™, to advance marine science, research and education.

Together, NOAA and Proteus Ocean Group seek to develop a deeper understanding of the ocean environment and reveal solutions to some of the planet’s most pressing concerns, including those related to climate change.

PROTEUS™, the first underwater site of this stature, is set to be built and will be located off the Caribbean island of Curacao.

It will serve as an underwater habitat where scientists, innovators, private citizens, the public sector and global customers can live underwater to study the ocean environment for extended periods of time.

In addition to state-of-the-art scientific laboratories, living quarters, and an underwater garden for food production, PROTEUS™ will include a full-scale video production facility to provide live streaming for research and educational programming.

“This partnership has the potential to greatly expand our capabilities in studying the ocean,” said Jeremy Weirich, the director of NOAA Ocean Exploration.

“By living underwater for extended periods in this new ocean laboratory, we’ll be able to unlock the ocean’s mysteries so that we can better manage, sustainably use, protect and appreciate its resources.”

Under the new cooperative research and development agreement, NOAA and Proteus Ocean Group will work together to identify opportunities for research using the unique capabilities of PROTEUS™.

NOAA will provide access to scientific experts, vessels and other technology, expedition plans and mission results relevant to PROTEUS™ activities, as well as access to shoreside facilities and programs throughout the agency’s mission portfolios of the ocean, weather, climate and coastal science.

Proteus Ocean Group will share data and insights related to the development phase of the underwater habitat.

Fabien Cousteau, founder and Chief Oceanic Explorer of Proteus Ocean Group said, “On PROTEUS™ we will have unbridled access to the ocean 24/7, making possible long-term studies with continuous human observation and experimentation.

With NOAA’s collaboration, the discoveries we can make — in relation to climate refugia, super corals, life-saving drugs, micro environmental data tied to climate events and many others — will be truly groundbreaking.

We look forward to sharing those stories with the world.”

The partners may undertake joint expeditions, exchange personnel and share methods of operation related to missions to study the ocean environment.

They will also work together to communicate their activities to increase public engagement in marine science.

The agreement supports the goals of both partners to better understand the impacts of climate change on the ocean, increase public engagement in ocean exploration and improve decisions related to ecosystem health and resilience.

Thursday, May 11, 2023

We found long-banned pollutants in the very deepest part of the ocean

From The Conversation by Anna Sobek

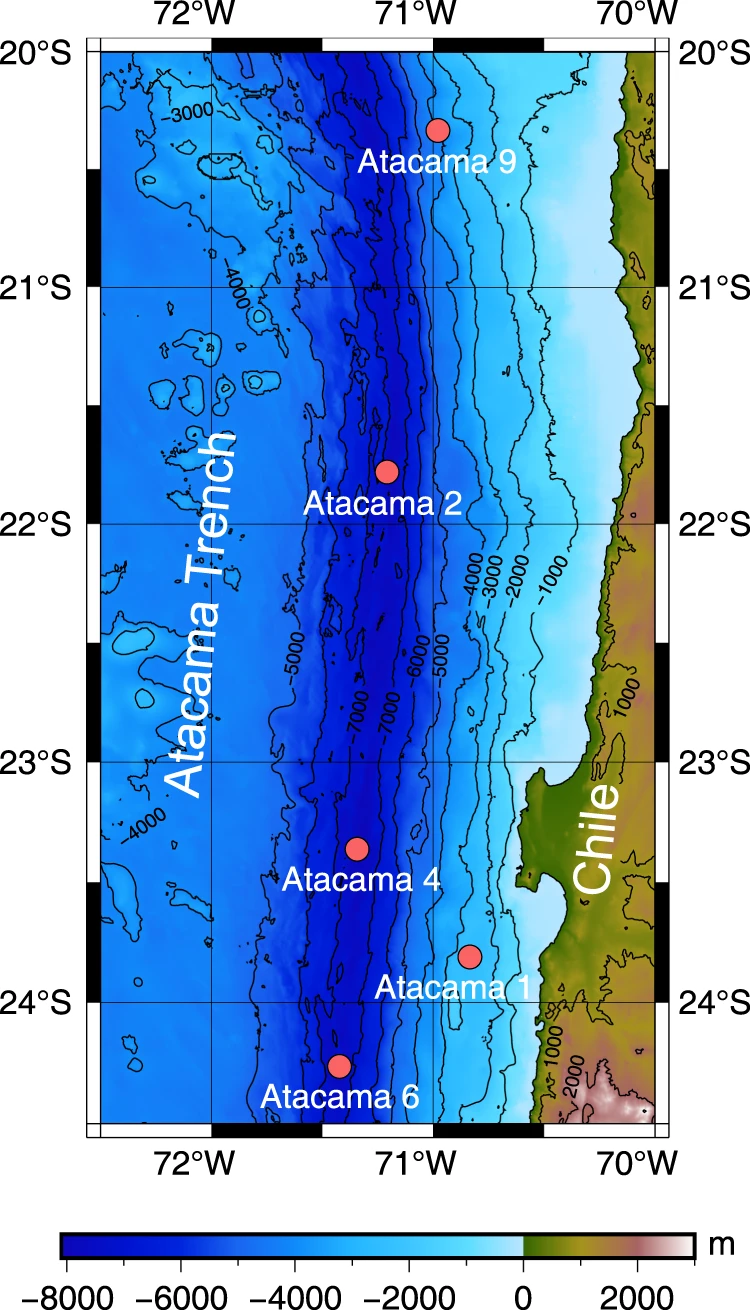

I was part of a team that recently discovered human-made pollutants in one of the deepest and most remote places on Earth – the Atacama Trench, which goes down to a depth of 8,000 meters in the Pacific Ocean.

The presence of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in such a remote location emphasises a crucial fact: no place on Earth is free from pollution.

PCBs were produced in large quantities from the 1930s to the 1970s, mostly in the northern hemisphere, and were used in electrical equipment, paints, coolants and lots of other products.

In the 1960s, it became clear they were harming marine life, leading to an almost global ban on their use in the mid-1970s.

However, because they take decades to break down, PCBs can travel long distances and spread to places far from where they were first used, and they continue to circulate through ocean currents, winds and rivers.

Our study took place in the Atacama Trench, which tracks the coast of South America for almost 6,000km.

Its deepest point is roughly as deep as the Himalayas are high.

We collected sediment from five sites in the trench at different depths ranging from 2,500m to 8,085m.

We sliced each sample into five layers, from surface sediment to deeper mud layers, and found PCBs in all of them.

Pollutants stick to dead plankton

In that part of the world, ocean currents bring cold and nutrient-rich waters to the surface, which means lots of plankton – the tiny organisms at the bottom of the food web in the oceans.

When plankton die, their cells sink to the bottom, carrying with them pollutants such as PCBs.

But PCBs don’t dissolve well in water and instead prefer to bind to tissues rich in fat and other bits of living or dead organisms, such as plankton.

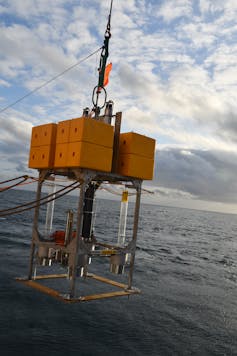

Anni Glud/SDU, Author provided

Since seabed sediment contains a lot of remnants of dead plants and animals, it serves as an important sink for pollutants such as PCBs.

About 60% of PCBs released during the 20th century are stored in deep ocean sediment.

A deep trench like the Atacama acts like a funnel that collects bits of dead plants and animals (what scientists refer to as “organic carbon”) that come falling down through the water.

There is a lot of life in the trench, and microbes then degrade the organic carbon in the seafloor mud.

We found that the organic carbon at the deepest locations in the Atacama Trench was more degraded than at shallower places.

At the greatest depths, there were also higher concentrations of PCB per gram of organic carbon in the sediment.

The organic carbon in the mud is more easily degraded than the PCBs, which remain and can accumulate in the trench.

The storage of pollutants means ocean sediment can be used as a rear-view mirror on the past.

It is possible to determine when a sediment layer accumulated on the seafloor, and by analysing pollutants in different layers we can gain information about their concentrations over time.

The sediment archive in the Atacama Trench surprised us.

PCB concentrations were highest in the surface sediment, which contrasts to what we usually find in lakes and seas.

Typically, the highest concentrations are found in lower layers of sediment that were deposited in the 1970s through to the 1990s, followed by a decrease in concentrations towards the surface, reflecting the ban and reduced emissions of PCBs.

For now, we still don’t understand why the Atacama would be different.

It is possible that we didn’t look at the sediment closely enough to detect small variations in PCBs, or that concentrations have not yet peaked in this deep trench.

These concentrations are still quite low, hundreds of times lower than in areas close to human pollution sources such as the Baltic Sea.

But the fact we have found any pollution whatsoever shows the magnitude of humanity’s influence on the environment.

What we can say for sure is that the more than 350,000 chemicals currently in use globally come at a cost of polluting the environment and ourselves.

Pollutants have now been found buried below the bottom of one of the world’s deepest ocean trenches – and they’re not going anywhere.

- IFLScience : Human-Made Toxin PCB Found Lurking 8,000 Meters Deep In The Ocean

- ScienceDaily : Environmental toxin PCB found in deep sea trench

- Earth : Shocking: Deepest parts of the ocean polluted with PCB chemicals

- Nature : Organic matter degradation causes enrichment of organic pollutants in hadal sediments

Wednesday, May 10, 2023

A mystery in the Pacific is complicating climate projections

Category 5 Hurricane Ian ravaged beachfront property in Bonita Springs, Florida, as seen here on Sep.

Category 5 Hurricane Ian ravaged beachfront property in Bonita Springs, Florida, as seen here on Sep.Ian — the nation’s third-most expensive weather disaster on record — is among 29 hurricanes, including 13 major hurricanes, churned out by the Atlantic from 2020 to 2022, or roughly 30% more than the average for a typical three-year span.

The period was dominated by La Niña conditions, which tend to enhance hurricane activity in the Atlantic.

(Image credit: Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

Nothing has a bigger influence on year-to-year variations in the global climate than the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, commonly called ENSO.

And the tropical waters at the heart of ENSO aren’t behaving exactly as climate scientists expected they would in a warming world, with potentially major implications for Atlantic hurricane seasons, droughts in the U.S. Southwest and the Horn of Africa, and other weather phenomena around the world.

ENSO is a recurring ocean-and-atmosphere pattern that warms and cools the eastern tropical Pacific through El Niño and La Niña events that last from one to three years.

Once El Niño or La Niña emerges, the odds reliably shift toward hotter, colder, wetter, or drier conditions for various parts of the globe, from Oceania to North America to Africa.

But though ENSO’s effects are well known, the phenomenon itself is notoriously tough to predict.

And its slippery nature is complicating crucial multi-decade projections of climate.

Many aspects of human-caused climate change are playing out as long predicted, including overall warming of the global atmosphere and oceans as well as the intensification of rainfall extremes and the drying of many subtropical areas.

Not so for ENSO.

Top global climate models have predicted for more than 20 years that the tropical Pacific would gradually shift toward an “El Niño-like” state, with the surface waters warming more rapidly toward the east than toward the west.

Instead, just the opposite is going on.

The western tropical Pacific has warmed dramatically, as predicted, but unusually persistent upwelling of cool subsurface water has led to a slight drop in average sea surface temperature over much of the eastern tropical Pacific.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Trend in sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific Ocean from 1982 through 2022.

Red (blue) shading in the map indicates trends toward more positive (negative) sea surface temperatures.

(Image credit: NOAA/climate.gov, data from NCEI OISSTv2.1)

The result is a strengthening west-to-east temperature contrast that increasingly resembles La Niña.

Scientists expect that El Niño events will continue to occur – such as the one predicted to arrive later this year – but they will take place on a backdrop of an ocean that looks more like La Niña.

All this is far more than an esoteric science matter.

According to an ENSO Blog entryposted Jan. 26 at climate.gov: “How the sea surface temperature trend pattern will change has profound, worldwide implications. … If you are trying to make decisions based on projections of the future, you need to know the answer.

And, at this moment, there is some significant (perhaps even growing) debate that surrounds it.”

Among the impacts that could be notably different in a La Niña-dominated world:Atlantic hurricane activity is substantially higher on average during La Niña than during El Niño.

(There are occasional exceptions, such as the very wet winter of 2022-23 in the Southwest.)

There are hints — though not yet enough cases to pass statistical muster — that La Niña events themselves are becoming more frequent, which would go hand in hand with the evolving Pacific backdrop.

For example, since mid-2003, there have been 10 “years” (July to June) when La Niña conditions predominated, but only six for El Niño.

Among years when the moderate-strength threshold was reached, seven were La Niña but only two were El Niño.

The La Niña-like temperature contrast in the tropical Pacific has now been strengthening for so long that it’s gotten tougher to ascribe to natural variability.

It could be chalked up to a cool phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, another recurring weather pattern that can span 20 to 30 years.

Yet that phenomenon is largely influenced by ENSO itself.

Climate experts are thus ramping up efforts to diagnose what it is that the state-of-the-art models could be missing and whether the long-expected El Niño-like trend may yet turn up later in the century.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.An aerial view of a property surrounded by flood water on Dec.

9, 2022, in Louth, Australia, about 400 miles northwest of Sydney.

Flooding across vast swathes of southeastern Australia during the La Niña summer of 2022-23 turned properties into islands.

The highest river levels in decades occurred at many flood-hit communities across the state.

A few months earlier, flooding was even more widespread over eastern Australia, leading to one of the nation’s worst weather disasters on record and more than $4 billion in damage.

(Image credit: Jenny Evans/Getty Images)

At the core of ENSO is the Walker Circulation, the large-scale flow of air over the Pacific tropics.

On average, air rises above the very warm waters of the western Pacific and sinks across the eastern Pacific, where chilly water predominates.

Completing the Walker Circulation loop (as shown in Figure 3 below) are westward flow a few miles above the Pacific tropics and eastward flow – the famed trade winds – at the surface.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.This schematic of average (neutral) conditions over the Pacific Ocean shows the Walker Circulation, with rising air and showers and thunderstorms to the west and descending air to the east.

Trade winds (surface arrows) push warm water toward the west, allowing colder water to upwell toward the east.

The depth of the upper Pacific Ocean is exaggerated in this schematic.

(Image credit: climate.gov)

When the Walker Circulation is strong, as it is during La Niña, the east-to-west-blowing trade winds are boosted and there is more upwelling of cold water off Ecuador and Peru.

When the Walker Circulation weakens, the trade winds slacken or even reverse, and the resulting westerly surface winds can push warm water all the way to the South American coast.

The usual upwelling weakens, and an El Niño event is in place.

The warm water leads to rising air thousands of miles farther east than usual, helping to suppress the Walker Circulation and torquing other weather patterns far away.

Given that El Niño is fighting against the grain of the usual atmospheric and oceanic conditions, it normally takes only about nine to 12 months before the tropics swing back toward a more typical Walker Circulation.

In contrast, La Niña — with an extra-strong version of the Walker Circulation — can persist or recur for as long as three consecutive years, as it did from 2020-21 to 2022-23.

There’s no doubt that the tropical Pacific has behaved in more of a La Niña-like than El Niño-like fashion over the past several decades.

The questions now center on whether the trend might still be natural variability — and if it’s not, what’s forcing it to happen.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.The left column shows the relevant processes in the preindustrial climate and the right column shows how La Niña-like conditions could be reinforced.

(This schematic does not show the final state).

Technical Details: Left panel: Showers and thunderstorms are strongest in the western Pacific where sea surface temperature is the highest.

Latent heating warms aloft, and evaporation cools the ocean surface.

In the eastern Pacific, the thermocline is closest to the surface.

Right panel: Under greenhouse-gas warming, a uniform surface heat flux into the Pacific Ocean causes the sea surface temperature to rise, but in the eastern tropical Pacific, the upwelling of cold water counters the forced warming.

As a result, the zonal sea surface temperature gradient increases.

(Image credit: climate.gov)

One of the first and most persistent among scientists looking into the perplexing sea surface temperature trend has been Richard Seager of Columbia University.

“We first wrote a paper on this in 1997,” he said.

Although less than 20 years of routine satellite data had been gathered from the tropical Pacific at that point, sea surface temperature data collected by ships extended back to the 1850s.

Since that 1997 study in Science, led by Seager’s colleague Mark Cane at Columbia, the sheer accumulation of satellite and buoy data on sea surface temperatures has supported the notion that the eastern tropical Pacific is cooling.

A 2019 paper gave the ideas new prominence.

“We showed using all the available models just how robust the actual discrepancy is [between models and observations], and we also provided a simple model to show how this might be happening,” Seager said.

“I think that moved the ball a little bit … I’m certainly very gratified [the idea] has gained traction now, including with funding agencies.”

Michelle L’Heureux tracks the variable nature of ENSO as closely as anyone.

She’s the physical scientist who coordinates the monthly ENSO updates released by the NOAA/NWS Climate Prediction Center.

L’Heureux noticed the acceleration of the Walker Circulation close to a decade ago.

In 2022 she joined lead author Sukyoung Lee of Pennsylvania State University, together with Seager and others, for an overview paperthat summarized the state of observations, simulations, and theories on where ENSO is heading.

“It’s exciting to see that others are now doing more work on the topic and coalescing around these ideas,” L’Heureux said.

At the National Center for Atmospheric Research, senior scientist Clara Deser, a longtime ENSO researcher, isn’t yet ready to dismiss natural variability as part of the picture.

However, she adds: “There may be multiple causes for the La Nina-like cooling trend in the eastern tropical Pacific, not just a single one.”

The cold, remote Southern Ocean could be a big part of the Pacific’s puzzling trend.

Much like the eastern tropical Pacific, the Southern Ocean is one of the few other areas on Earth where sea surface temperatures have cooled rather than warmed since the 1980s, in spite of pronounced surface warming over the Antarctic Peninsula and concerns about longer-term deep-ocean warming.

A number of studies have already found links between the Southern Ocean and ENSO behavior.

Usually it’s the tropical Pacific that triggers weather and climate effects at middle and higher latitudes, but the Southern Ocean itself may be influencing ENSO, based on recent work that includes a 2022 study led by Columbia’s Yue Dong as well as a paper by Deser and colleagues that’s now in process.

Adding to the complexities at hand, it’s possible that whatever factors are now pushing the tropical Pacific toward a La Niña-like state will eventually get overwhelmed by longer-term global warming.

Figure 5.

Figure 5.Schematic showing a possible mechanism toward an El Niño-like state, as reviewed in Lee et al.

(2022). The left column shows the relevant processes in the preindustrial climate and the right column shows how these same processes initially respond to greenhouse-gas warming (this schematic does not show the final state).

Technical Details: Left panel: Convection is strongest in the western Pacific where sea-surface temperatures are the highest.

Latent heating warms aloft, and evaporation cools the ocean surface.

Right panel: Sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific increase leading to more condensational heating aloft and a higher tropopause, which increases dry static stability and gross moist stability, thus weakening the Walker circulation.

At the same time, evaporative cooling and cloud shading are more sensitive to warming in the western Pacific, which weakens the zonal sea surface temperature gradient.

(Image credit: climate.gov)

“There are some good physical reasons for why we would expect to eventually end up with eastern-Pacific warming,” said Ulla Heede, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences who’s published several recent papers on this two-stage concept.

In a subsequent study, drawing on a wide range of simulations carried out for the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment, Heede and Alexey Federov of Yale University found some but not all models depicting this two-phase response after an abrupt injection of carbon dioxide.

In one set of experiments with models that fully couple the atmosphere and ocean, Heede and colleagues found the observed La Niña-like state emerging and persisting for 20 to 100 years, depending on how quickly carbon dioxide is added.

Somewhere between 50 and 100 years, the subtropical ocean circulation weakens and warms enough to cut down on cold upwelling, pushing the system toward El Niño-like conditions.

The difficulty in modeling ENSO exists not only in century-scale climate simulations but also in the yearly-scale models that are run regularly to assess where ENSO is headed right now.

This adds a hefty dose of challenge to the monthly ENSO outlooks issued by L’Heureux and colleagues at NOAA and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.(Image credit: NOAA/IRI)

There are good reasons why ENSO is so difficult to capture in both seasonal and multi-decadal modeling.

For just one example, consider the thermocline, the oceanic boundary that separates warmer near-surface water from cooler deep water.

Across the tropical Pacific, the thermocline depth normally varies from about 450 feet in the west to only about 50 feet in the east.

That’s paper-thin when compared to the 12,000 miles of distance from west to east along the Pacific equator, and thus difficult for global climate models to capture with precision.

When a NOAA forecast of ENSO does “bust,” it’s usually because of a false alarm from the models, and it usually involves El Niño.

As documented by Columbia’s Michael Tippett, the North American Multi-Model Ensemble projected that the eastern Pacific would warm between May and August in 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2017.

All of these model forecasts were wrong.

Only one of those four years, 2014, saw the Pacific make it to the El Niño threshold.

That didn’t happen until autumn 2014, though, and the event was so borderline that it may end up being reclassified as neutral.

L’Heureux led a 2022 study on how the cooling trends in the eastern Pacific may be complicating ENSO forecasts; she’s also presenting a paper on the topic at the European Geophysical Union’s annual meeting in late April.

An even bigger challenge than modeling ENSO may be communicating to stakeholders how they can prepare for ENSO-related trends that could be starkly different from what’s been long expected.

“East Africa has been struggling with drought for most of the 21st century, including the last few years,” Seager noted.

“The models predict that that region should be getting wetter, and it hasn’t.

The fact that it hasn’t is largely consistent with what the equatorial Pacific Ocean is doing.

“Food security in East Africa is a perennial problem.

The implications are just enormous.”

Figure 7.

Figure 7.Somali refugees return from collecting water at the edge of the Dagahaley refugee camp, which makes up part of the giant Dadaab refugee settlement, on July 22, 2011, in Dadaab, Kenya.

Five consecutive biannual wet seasons failed during the three years of La Niña conditions from 2020 into early 2023, leading to the worst drought to affect the Horn of Africa in six decades.

The drought, together with the ongoing civil war in Somalia, has resulted in an estimated 12 million people whose lives are threatened.

(Image credit: Oli Scarff/Getty Images)

Isla Simpson, a colleague of Deser’s at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, is now co-organizing a workshop to examine where observational trends differ from climate models, including ENSO and other areas.

“We’re only really starting to be at the point where we’re able to observe these trends over a long enough period to know if the models are actually wrong,” Simpson said.

The U.S. Southwest will experience the landscape-parching effects of hotter weather no matter what ENSO does.

But any continued tilt toward La Niña-like conditions would also tend to favor the prolonged deficits in rainfall and mountain snowfall that have plagued the region since 2000.

Even the bountifully wet winter of 2022-23 is unlikely to turn the long-term tide.

“The combined impact of warmer temps and potentially lower precipitation is not good news,” Simpson notes.

As summarized by Heede: “Climate scientists love studying what happens in the tropical Pacific, but my point of view is that no one’s living there.

We have to make the link from what happens in the tropical Pacific to what happens over land.”

Links :

Tuesday, May 9, 2023

American Samoa criticizes US plan to expand size of Pacific marine sanctuary

Pacific Remote Marine National Monument.

Normally, a unique ocean current brings cold water up from the deep to make the underwater region vibrant with coral, nutrients, fish and sharks .

President Joe Biden’s plan to expand marine sanctuaries around the United States’ remote Pacific islands has been greeted with dismay in American Samoa, where officials fear a heavy blow to the U.S.

territory’s economically crucial tuna industry.

American Samoa Gov. Lemanu Mauga, in a recent letter to Biden, criticized zero consultation with the territory about the sanctuary expansion and said it was contrary to Biden’s own executive orders aiming to improve the lives of marginalized Americans.

The lack of consultation also could reflect badly on the U.S. government at a time when it is trying to show a renewed commitment to Pacific island countries in response to China’s burgeoning economic and diplomatic presence in the region.

“American Samoa is repeatedly left out of the conversation of what is best for our communities,” Mauga said in the letter.

“We are disappointed that actions that could cripple the economy of a U.S. territory would be taken without the consultation of its people.”

The total area of the expanded sanctuary would be 2 million square kilometers (770,000 square miles), larger than the Gulf of Mexico, compared with about 1.3 million square kilometers (495,000 square miles) now.

It encompasses waters around several islands, atolls and reefs that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says are “home to some of the most diverse and remarkable tropical marine life on the planet.”

The islands and atolls are uninhabited save for visiting researchers and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service staff.

The tropical waters are ideal for skipjack tuna which travel the equator in search of schools of small fish to feed on.

The oceanic administration is accepting public submissions on the sanctuary expansion until June 23 after Biden last month set the designation process in motion.

“The region's diverse habitats and pristine reefs provide a haven for a variety of fish, invertebrates, seabirds, sea turtles, and marine mammals – many found nowhere else in the world – and are an ideal laboratory for monitoring the effects of climate change,” it said this month.

Fish and Wildlife Service shows birds at Johnston Atoll within the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Fish and Wildlife Service via AP

Two-hundred nautical mile zones (370 kilometers) around Wake Atoll, Johnston Atoll and Jarvis Island are already part of the sanctuary.

The proposed expansion would increase the extent of the sanctuaries around Howland and Baker Islands and Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll.

Tuna fishing provides about 5,000 jobs in American Samoa – where a South Korean-owned StarKist tuna cannery is the territory’s largest business – but has been in decline.

The American Samoan islands, located to the south of the marine sanctuary, are home to less than 50,000 people after suffering a shrinking population for at least the past decade.

Handing China ‘a win in the Pacific’

Biden’s push to expand the sanctuary could give Beijing a victory in the Pacific, American Samoan congresswoman Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen told a Congressional hearing last month on U.S.

strategy in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

“I think he [Biden] took some bad advice on this ocean conservation proposal that may hand PRC a win in the Pacific,” the Republican congresswoman said, using the acronym for China’s official name, the People’s Republic of China.

“The president treated our territory less favorably than PRC treats Pacific islands that are aligned with Beijing or that are at risk of surrendering to PRC domination,” she said.

America’s allies in the North Pacific such as Federated States of Micronesia “must wonder if the U.S.

is prepared to out-compete PRC,” Amata said.

The U.S.-flagged tuna purse seine fleet, which supplies the American Samoa tuna cannery, has dwindled to 15 vessels from 38 in 2018, according to the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, which oversees the fisheries of American Samoa, Hawaii, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands and the uninhabited Pacific islands.

The council has opposed enlargement of the sanctuary.

In a special issue of its newsletter in August last year, it said the sanctuary expansion would in practice restrict only U.S.-flagged vessels from fishing.

Closing the waters of Howland and Baker Islands and Palmyra Atoll and Kingman Reef would force U.S. vessels to fish farther away from American Samoa and deliver their catch to ports in places such as Ecuador, it said.

Credit: Michael Griffin/U.S.Coast Guard via AP

Globally, the deep sea fishing industry has become notorious for exploitative and dangerous working conditions.

In 2015, Associated Press reporters exposed slavery in the Southeast Asian fishing industry, which led to the rescue of hundreds of men from a remote Indonesian island.

The fishery management council said allowing the regulated U.S.fishing industry to be replaced by foreign fishing vessels could “exacerbate existing conservation issues for protected species and even socioeconomic issues such as food security and human rights.”

U.S. vessels are a small component of the Pacific purse seiner and longliner fishing fleets.

Most are flagged to Pacific island countries and nations such as China, Taiwan and Japan.

The marine sanctuary’s planned enlargement is part of U.S. efforts to protect 30% of its lands and waters by 2030.

The sanctuary, said the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, would also recognize the importance of Pacific indigenous knowledge and languages and the “cultural connections between lands, waters, and peoples.”

Mauga, the American Samoa governor, said the burden of the conservation effort is falling disproportionately on the Pacific and American Samoa.

“If the attempt in this designation was to better protect Pacific communities, I ask that you please consult with us before closing access to our waters,” he said in his March 30 letter to Biden.

“Without access to these traditional fishing grounds, our tuna industry and entire economy will be annihilated,” Mauga said.

Links :

Monday, May 8, 2023

The voyage of the Sarimanok 1986

Sunday, May 7, 2023

The sailor (full movie)

- ClassicSailor : In memory of Paul Erling Johnson

- Scuttlebutt : Eight Bells: Paul Erling Johnson

- Cruising World : A Chat with Sailing Legend Paul Johnson