Saturday, September 7, 2024

Diving bell ship - working underwater without getting wet

Inside the weirdest ship that lets you inside the magical diving bell ship

that lets you walk underwater without getting wet

Friday, September 6, 2024

How Australia put evolution on Darwin’s mind

From The Smithsonian by Tony Perrotet

Meeting the great-great-grandson of the great, great naturalist Charles Darwin demands total immersion in Australian nature.

The first step is locating Chris Darwin’s abode, hidden in the foothills of a vast, rugged labyrinth of gorges and valleys called the Blue Mountains.

From the sleepy hamlet of Glenbrook, a narrow paved road descends into lush eucalyptus forest, where, alone apart from the birds, I spotted a tiny mailbox.

I slowly edged my rented vehicle down a sloped driveway flanked by raw sandstone outcroppings, wondering how I would ever manage to reverse back out if this turned out to be the wrong address.

The driveway finally ended, much to my relief, at a brick house almost engulfed in foliage.

Beyond this point lay a string of nature reserves and national parks—2.5 million acres of pristine bush, just 40 miles west of Sydney.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/88/4d8864d5-4aca-4ee6-9377-1a1dd7d2b34e/dec15_e02_darwin.jpg) “You

could say that saving species is in my blood,” says Chris Darwin, a

conservationist who lives in the mountains explored by his

great-great-grandfather.

“You

could say that saving species is in my blood,” says Chris Darwin, a

conservationist who lives in the mountains explored by his

great-great-grandfather.Adam Hollingworth / Hired Gun

Darwin bounded out of his doorway to greet me with a hearty handshake along with two curly-haired boys.

The lanky, 53-year-old Chris is far more the eccentric Englishman than his sober ancestor Charles.

Completely barefoot, he sported a crimson tie with a bird pattern, and britches held up by red suspenders—a Tolkien character in mufti, as if the forest-dwelling wizard Radagast the Brown had gone to Oxford.

“Shall we go into the rainforest?” Darwin asked in his cultivated accent, as his sons hung off his arms in the kitchen.

“I think we must really talk about Charles Darwin there. He loved rainforest. He said it left him intoxicated with wonder.”

“Let’s go to the vines!” 9-year-old Erasmus cried out.

“No, the waterhole!” chirped Monty, age 7.

Before we could set off, Darwin insisted we pack hot tea and Christmas cake as sustenance.

Soon I was stumbling down a steep dirt track, balancing a steaming cup in one hand and a plate in the other, as the brilliant Australian light flickered though the trees.

Shafts illuminated the rainforest floor, a succulent carpet of native ferns and fungi.

Climbing vines with evocative names like “wonga wonga” and “wombat berry” snaked upward around the trunks.

“Watch out for that jumping jack nest!” Darwin laughed, nodding to a swarming mound of ants.

“They give a hell of a sting.”

After a slow and (to me) precarious descent, we arrived at a natural pool like a black mirror in the ground.

We perched on mossy rocks and attempted morning tea, while the boys roared like wild things, throwing boulders into the water to splash us, Chris all the while smiling indulgently.

We perched on mossy rocks and attempted morning tea, while the boys roared like wild things, throwing boulders into the water to splash us, Chris all the while smiling indulgently.

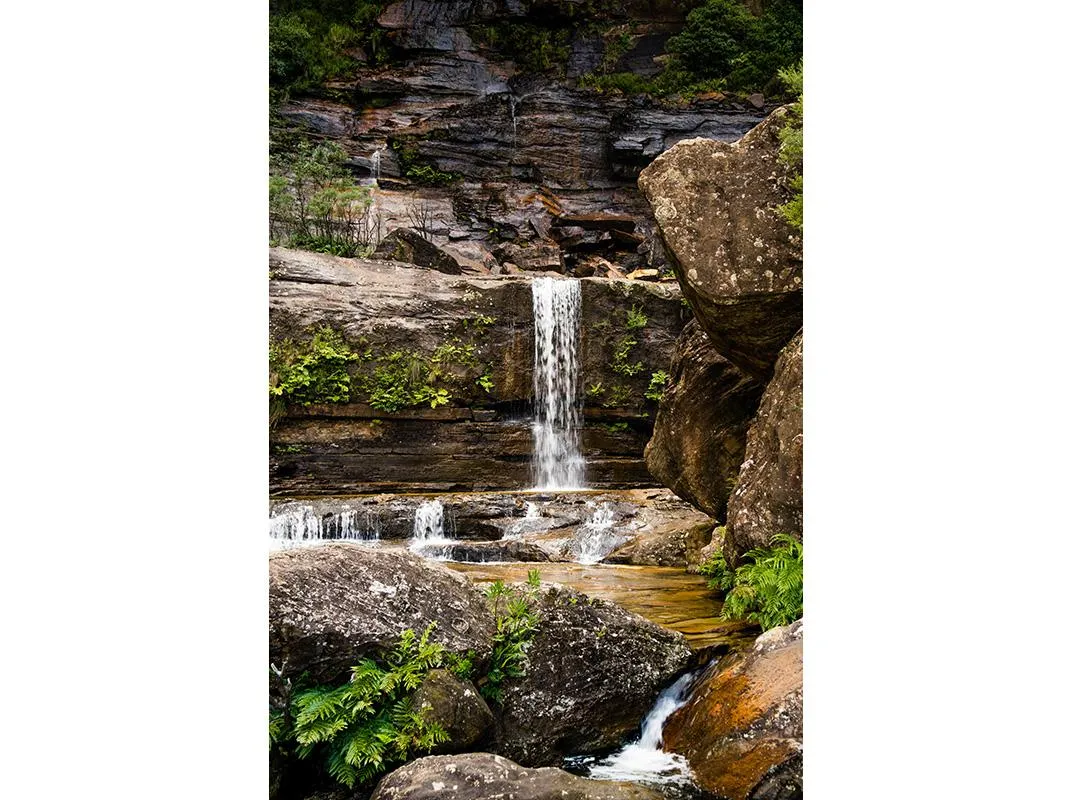

An hour’s drive south, Wentworth Falls offers views Darwin described as “most magnificent, astounding and unique.” Joe Wigdahl

There is a satisfying historical logic to the fact that one of the most vigorously nature-worshiping of Charles Darwin’s 250-odd direct descendants—a man who gave up a successful career in advertising in London to be a climbing guide and environmental activist, not to mention an expert on his ancestor’s storied life—ended up living in this particular pocket of the Antipodes.

“Charles Darwin thought the Blue Mountains the most beautiful part of Australia,” Chris said, gazing at the exotic greenery, thick with coachwoods, sassafras and the glossy green leaves of the lilly pilly.

“And of course, so do I.”

1846 "General Chart of Australia", showing coasts examined by HMS Beagle during the third voyage in red, from John Lort Stokes' Discoveries in Australia

Few non-Australians are even aware that the 26-year-old Charles visited the continent in early 1836 on his round-the-world voyage in the HMS Beagle.

The fresh-faced Cambridge grad had been invited on the Beagle because of his passion for natural history, and when he arrived in Australia, after traveling around Cape Horn and up South America’s Pacific coast, his radical ideas were as yet unformed.

In fact, young Charles had been groomed for a career in the clergy.

As had been his custom, he collected specimens in Australia to take back to London for further study over the coming decades.

Most important, it was Darwin’s 11-day adventure in the Blue Mountains that kick-started his thinking on evolution, as historians have shown from his diary, letters and field notes.

The visit would prove as influential for his path to On the Origin of Species, published 23 years later, as his canonical studies of the Galápagos Islands.

“When I was a child, my father taught me all about Charles Darwin’s visit here,” Chris said.

“Our family always viewed him as a very romantic figure, and Australia was one of the wonderful exotic places he went to. We liked to imagine him on horseback, riding through the summer heat wave, discovering marvelous things.”

On that 1836 excursion, Darwin was puzzled by Australia’s strange wildlife, including the duck-billed platypus—the furry, semi-aquatic mammal whose appearance is so freakish that British biologists thought the first specimens sent to London were a hoax, fabricated from different animals.

Darwin was able to observe it in its natural setting, which upset his religious assumptions.

“We were told from a very young age about the ‘platypus moment,’ which was a real epiphany for Darwin,” Chris said.

Although his conclusions took two decades to reach, the seeds of his revolutionary theories on natural selection were sown only a few miles from where Chris now lived.

The fresh-faced Cambridge grad had been invited on the Beagle because of his passion for natural history, and when he arrived in Australia, after traveling around Cape Horn and up South America’s Pacific coast, his radical ideas were as yet unformed.

In fact, young Charles had been groomed for a career in the clergy.

As had been his custom, he collected specimens in Australia to take back to London for further study over the coming decades.

Most important, it was Darwin’s 11-day adventure in the Blue Mountains that kick-started his thinking on evolution, as historians have shown from his diary, letters and field notes.

The visit would prove as influential for his path to On the Origin of Species, published 23 years later, as his canonical studies of the Galápagos Islands.

“When I was a child, my father taught me all about Charles Darwin’s visit here,” Chris said.

“Our family always viewed him as a very romantic figure, and Australia was one of the wonderful exotic places he went to. We liked to imagine him on horseback, riding through the summer heat wave, discovering marvelous things.”

On that 1836 excursion, Darwin was puzzled by Australia’s strange wildlife, including the duck-billed platypus—the furry, semi-aquatic mammal whose appearance is so freakish that British biologists thought the first specimens sent to London were a hoax, fabricated from different animals.

Darwin was able to observe it in its natural setting, which upset his religious assumptions.

“We were told from a very young age about the ‘platypus moment,’ which was a real epiphany for Darwin,” Chris said.

Although his conclusions took two decades to reach, the seeds of his revolutionary theories on natural selection were sown only a few miles from where Chris now lived.

“It was here that Charles Darwin questioned Creationism for the first time,” Chris said suddenly, between sips of tea.

“He came out of the closet, basically.”

***

When the ten-gun sailing vessel HMS Beagle hove into Sydney’s glittering harbor on January 12, 1836, before a light morning air, according to his journals, Darwin was in a fragile mood.

The voyage had already lasted four years, twice as long as expected, and he had been seasick all across the Pacific.

He was homesick and lovelorn, too, having recently learned that his teenage sweetheart, Fanny Owen, had married another.

Still, he was keen to explore the new British outpost, founded as a prison colony only 48 years earlier: “We all on board are looking forward to Sydney, as to a little England,” he wrote.

His optimism was shaken by his first glimpse of the Australian landscape, which was suffering from a protracted drought.

Despite impressive sandstone cliffs, he found the bush around Sydney Harbor made up of “thin scrubby trees (that) bespoke sterility.” Worse, no letters awaited the Beagle’s crew.

“None of you at home, can imagine what a grief this is,” he wrote pitiably to his sister Susan.

“I feel much inclined to sit down & have a good cry.” Darwin cheered up a little while strolling around Sydney, which boasted a population of 23,000, now mostly free settlers.

“My first feeling was to congratulate myself that I was born an Englishman,” he wrote in his diary, marveling at the stores full of fashionable goods, the carriages with liveried servants and the splendid mansions (although there were rather too many pubs for his liking).

The apparent industry made a pleasing contrast to the decay of Spain’s much older South American colonies.

Over the next few days, the colony’s democratic character unsettled him.

As a scion of England’s ruling class, he was disturbed to note that ex-convicts, once they had served their prison term, were now prospering in business and openly “reveling in Wealth.”

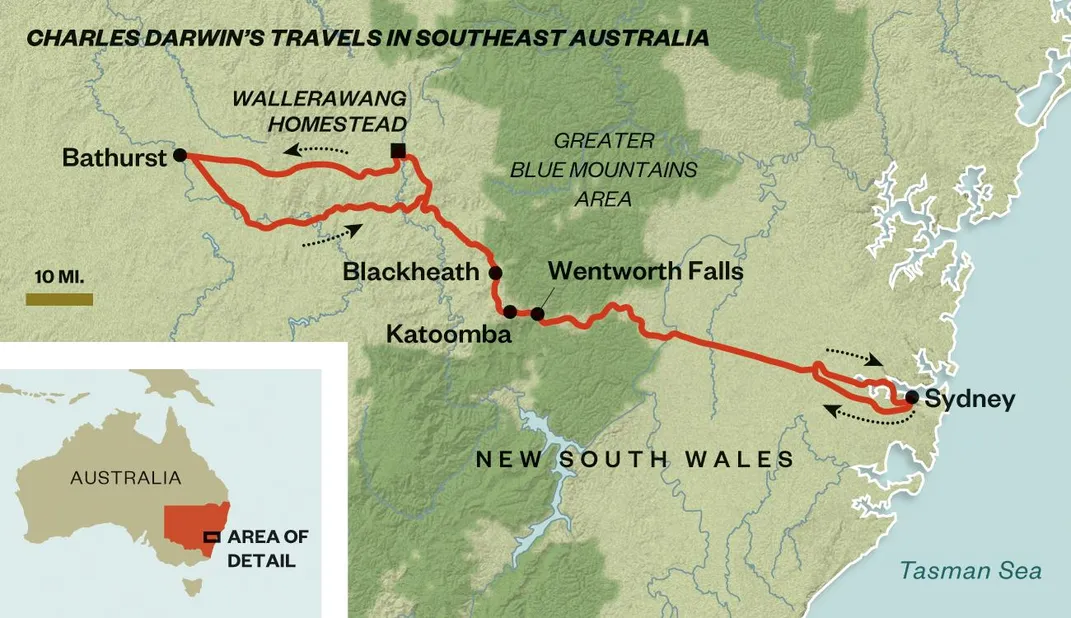

To plunge into his nature studies, Darwin decided to travel into the nearby Blue Mountains, where mysterious species (many already renowned among the British scientific community) thrived in a geologically unique setting.

He hired a guide (whose name is lost) and two horses.

A highway had been carved across the rugged landscape two decades earlier, but it was still difficult going.

He passed convict chain gangs under redcoat guard, and a party of aboriginals, who for a shilling threw their spears “for my amusement.” Having met the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego as well as the New Zealand Maoris earlier on the voyage, he condescended to find the aboriginals “good-humored & pleasant (and) far from the degraded beings as usually represented.” He predicted that aboriginal contact with convicts and rough settlers from British slums, who exposed them to alcohol and diseases, boded ill for their future.

As for the Blue Mountains, Darwin had expected “a bold chain crossing the country,” but instead found the scenery “exceedingly monotonous.” (The name originates from the bluish tinge, when seen from a distance, created by tiny droplets of evaporated eucalyptus oil in the air.) His opinion improved at Wentworth Falls, where above the roaring cascade he was astonished by sweeping views of the Jamison Valley.

Here were the “most stupendous cliffs I have ever seen,” he raved, each precipice topped with ancient forests, framing a “grand amphitheatrical depression” dense with untold numbers of eucalyptus trees, whose “class of view was to me quite novel.” He speculated that the valleys were carved by ocean currents.

In fact, the Blue Mountains are what remains of a dissected plateau, whose bedrock, deposited by the sea some 250 million years ago, has been eroded by wind and rivers over the eons.

Today, visitors can follow Darwin’s route, beginning at Sydney’s spectacular ferry terminal at Circular Quay, where the Beagle weighed anchor in front of today’s Opera House, and traveling the Great Western Highway into the crisp mountain air.

In the village of Wentworth Falls, the old Weatherboard Inn where Darwin spent the night is long gone, although his bush trail has been preserved as the Charles Darwin Walk, and it still makes the most exhilarating introduction to the Blue Mountains.

The two-mile path follows a creek through a waterlogged forest, known as “hanging swamp,” that is alive with native birds, including honeyeaters and screeching black cockatoos feasting on banksia trees, whose flowers resemble spiky yellow brushes.

It opens up with a flourish above the 614-foot-high waterfall, with untouched views of those golden cliffs.

It’s easy to see why Darwin was taken with the primeval view: One almost expects a long-necked dinosaur to lumber into the scene at any moment.

Human settlement has always felt tentative here.

The region was thinly populated by early aboriginal inhabitants compared with the warmer hunting grounds of the coast, although the people here did leave their mark in cave paintings of animals and hand prints.

With white settlement, a few roadside pubs and mining outposts took hold, and in the Victorian age, scenic villages such as Katoomba and Blackheath became vacation resorts.

Honeymooners from Sydney marveled at the Three Sisters, a trio of sandstone sculptural forms rising from the bush, and the Jenolan Caves, the world’s oldest cave complex, its 25 miles of tunnels filled with gleaming white stalactites and stalagmites of unearthly beauty.

The American naturalist John Muir stopped by on his 1904 world tour.

Today, the Blue Mountains still boast historic hotels like Lilianfels, where you can take tea and scones in rattan chairs, and the Hydro Majestic, a sprawling Art Deco gem reopened last year after a decade-long renovation.

The real attraction—the wilderness—still has a huge following of devoted Australian bushwalkers.

Today, seven national parks and an additional reserve are combined into the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, whose 2.5 million acres encompass underground rivers, spectacular waterfalls and natural swimming holes.

Some of its slot canyons are so steep that they have reportedly never been visited by humans.

There is a sense that anything can still be found here—a feeling that was proven in 1994, when a young fieldworker for the park service stumbled across a plant species that scientists had believed extinct for two million years.

David Noble was on a weekend hiking trip in a northern park with two friends, rappelling into remote canyons and spelunking.

“I wasn’t looking for anything new or unusual,” he recalled.

“We picked a gully off the map at random to explore.” As the trio stopped for lunch in a sheltered niche, Noble observed a cluster of unfamiliar trees looming over them 60 to 100 feet tall, and took a clipping back to the park lab.

The staff biologist was unable to recognize it, and a more scientific excursion was arranged.

It was soon ascertained that the tree, the Wollemi pine, matched fossils from the Jurassic era.

The discovery caused a sensation in scientific circles and among the Australian public, with tabloids calling the pine a “living dinosaur.” The original location of the specimens remains undisclosed to deter souvenir hunters and to protect the vulnerable plants from disease.

But the tree has since been cultivated; the public can see the pine in botanical gardens around Australia (including the hugely popular Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney), Europe, Taiwan and Japan and some places in North America, including at the Kingsbrae Garden in New Brunswick, Canada.

“Is there anything else out there in the mountains?” Noble mused.

“Well, I didn’t expect to find the Wollemi pine! If you look at the sheer [enormousness] of the parks, I wouldn’t be surprised what turns up.”

***

From the Jamison Valley, Charles Darwin headed to the frayed edges of colonial settlement, descending the western flanks of the mountains via Victoria Pass.

The climax of his trip occurred in an unexpected setting, a lonely sheep station (Australian for ranch) called Wallerawang, where he put up for two nights with the superintendent, an amiable Scot named Andrew Browne.

Darwin found the sandstone homestead sorely lacking (“not even one woman resided here”) and the young gent’s sensibilities were offended by the convict farmhands—“hardened, profligate men,” he judged, heavy-drinking, violent and “quite impossible to reform.” But, inspired as ever by nature, he made a horseback day trip on January 19 down into the glorious Wolgan Valley, where he collected rock samples.

The fauna fired his imagination, as he noted the kangaroo rat (also called a potoroo), electric-hued rosellas (native birds) and sulphur-crested cockatoos.

But his safari became more profound back at the Wallerawang homestead, when Darwin followed a stream in the cool of dusk and “had the good fortune to see several of the famous Platypus,” playing in the water.

These wildly peculiar monotremes (egg-laying mammals) were behaving exactly like the water rats he knew back home in England.

His companion, Browne, helpfully shot one so that Darwin could examine it more closely.

In the waning sun, Darwin sat by the creek and pondered why the animals of Australia were so eccentric in appearance.

The kangaroo rats had behaved just like English rabbits, and even as he considered this, a fierce-looking Australian ant lion dug the same conical pit before his eyes as the smaller English ant lion would do.

According to Frank Nicholas, a now-retired animal geneticist and co-author (with his wife, Jan) of Charles Darwin in Australia, this was a key moment: “The obvious question was, if you were an omnipotent creator, why would you bother going to all the trouble of designing two different species to occupy very similar ecological niches?”

Darwin’s diary entry for this day has become widely studied: “A Disbeliever in everything beyond his own reason, might exclaim, ‘Surely two distinct creators must have been (at) work; their object however has been the same & certainly in each case the end is complete.’” But the radical difference between the species was baffling: “Would any two workmen ever hit on so beautiful, so simple & yet so artificial a contrivance?” The remarks were expressed in cautious terms, Nicholas argues, because Darwin knew his notebooks would be read by Christian relatives back home.

(He adds a hasty Creationist disclaimer: “I cannot think so.

—The one hand has worked over the whole world.”) But one thing is certain, Nicholas says: “This was the first time that Darwin put such a question on paper.” Only when writing On the Origin of Species did he accept the implications of his heretical thought—that different species had in fact evolved from the same origin over millions of years, changing their characteristics to suit their environments.

“It would be one of the great understatements to call this a portentous moment,” writes University of Sydney professor Iain McCalman in Darwin’s Armada.

“At no other time on the Beagle voyage did Darwin raise the issue, and afterwards he buried it for a further twenty years.” In retrospect, it is as much of a eureka moment as Isaac Newton’s storied encounter with an apple.

“One thinks of Charles Darwin as a cold scientist,” adds Chris Darwin, “but there was real passion there.

He could stare for hours at an ant’s nest, or a rose in a garden.

In Wallerawang, he sat by himself, gazing at the dead platypus for hour after hour, thinking ‘It just doesn’t make sense.’ Why had God made the water rat for Europe and North America, and the platypus for Australia? It’s terrifying, really.”

***

Today, Wallerawang is a drowsy pastoral town with a pub or two.

Instead of the farm where Darwin stayed, there is now a muddy dam.

It was created in 1979 to supply a power station, sadly submerging the colonial homestead.

Since then, local pride in the connection to Charles Darwin has blossomed.

An elderly woman living in a caravan tended a small municipal park named after the naturalist, dominated by a sign: “Please Do Not Steal the Plants.” A few rocks have been arranged as an official memorial to the 1836 visit, complete with a bronze platypus statue.

The nearby Wolgan Valley, however, which Darwin saw on his day trip, still offers an unchanged view of the 1836 frontier.

It’s Australia’s answer to Monument Valley, an otherworldly plain surrounded by mesas, like an arena of the gods.

The core 4,000 acres are now a nature reserve as part of the luxurious Emirates Wolgan Valley Resort and Spa, where guests have their own bungalows, each with a private swimming pool.

The facility was created (surreally enough) by Emirates Group, the parent company of the airlines, to offset the carbon footprint of its aircraft.

(It also has a grove of Wollemi pine saplings, not far from a stream where platypuses can sometimes be spotted at dusk.)

My ultimate goal was one of the oldest structures in the Blue Mountains—a farmhouse dating from 1832 still nestled in a pasture with stunning views of the valley.

As the only white habitation in the valley at the time of Darwin’s trip, the naturalist would almost certainly have visited.

One of the tour guides now employed at the property, Nicholas Burrell, wearing an Akubra hat and R.M. Williams work boots, opened up the doors to the empty homestead for me, as wind whistled through the wooden boards, and opened a dark shed that had housed the farm’s ten convicts.

“I’ve got convicts on two sides of my family,” Burrell assured me.

Most modern Australians take pride in tracing criminal ancestors: Convicts were usually deported for petty theft or other minor offenses, and they are now seen as victims of an unfair system, creating a reverse aristocracy.

Burrell then showed me the mummified corpse of a rabbit, discovered by archaeologists when the foundations of the homestead were raised during restoration.

It had been buried under a corner post, an old Scottish tradition, he says, to protect the house from evil spirits.

In a country that once gave little heed to its past, the homestead is a rare survivor.

For me, standing on the creaking porch hung with rusty tools, I could finally imagine the young Darwin gazing out at this same ancient landscape, his imagination racing.

***

One of the many astute observations Charles Darwin made on his 1836 Australian tour was that the country’s native wildlife was in long-term peril.

While staying at Wallerawang, he saw English greyhounds easily chase down a potoroo, and noted that, thanks to overhunting, farming and introduced predators, settled areas around Sydney were already devoid of marsupials and emus.

In a startling continuity across the generations, Darwin’s great-great-grandson Chris has joined the campaign to halt extinction in Australia.

“My ancestor Charles discovered the origin of species,” Chris told me.

“I want to stop their mass disappearance.”

It wasn’t always obvious that Chris, who grew up in London, would fulfill his ancestral destiny.

“When I failed my school biology exam, it was quite a family crisis,” he recalled with a laugh.

“My father wondered if the species was devolving!” His teenage nickname became “The Missing Link.” But the Darwin name, he admits, opened doors.

“People hope to find a spark of Charles Darwin inside me, so there is more curiosity when they meet me as opposed to, say, Peter Smith.”

Chris Darwin was also raised to love nature, and in his 20s, he windsurfed around Britain and hosted what was, at the time, the world’s “Highest-Altitude Dinner Party,” on an Andean peak, with climbers in top hat, tails and ball gowns; the event raised money for charity and gained an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.

But he chose a career in advertising, which caused a lot of stress and unhappiness.

“I’m not embarrassed to say that I had a dark period in my life,” Chris says.

In 1991, at age 30, he attempted suicide.

He moved to the Blue Mountains to be surrounded by wilderness, and became a rock-climbing guide.

He was still a “climbing bum,” as he put it, five years later, when his grandmother left him an inheritance.

“I thought, here is a real opportunity to do something for others, as Charles would have wanted!” He donated 300,000 Australian dollars (about $175,000 in U.S.

dollars at the time) to an organization called the Bush Heritage Australia to create a private nature reserve in Charles Darwin’s name.

In 2003, the 265-square-mile reserve, one of 35 now managed by Bush Heritage, was established some 220 miles northwest of Perth.

It’s one of the world’s remotest environmental hot spots, where scientists have since found dozens of new and endangered plant, insect and bird species.

Chris is now taking his anti-extinction message to North America in what he is calling a PR campaign for Mother Nature.

The project will start next year or the year after.

He plans to meet 20 other direct descendants of Charles Darwin in Manhattan, all wearing beards, wigs and Victorian suits, to promote a regeneration program for an endangered species of moss endemic to New York State.

In California, there’ll be a black-tie dinner party high in the branches of a redwood tree, perhaps on the anniversary of Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir’s famous 1903 trek through Yosemite.

In Florida, he hopes to convince the Florida Panthers hockey team to adopt its namesake feline, of which only an estimated 70 survive today.

He thinks his peripatetic great-great-grandfather would have approved.

Darwin, C. R. 1842. The structure and distribution of coral reefs. Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836. London: Smith Elder and Co.

After traveling as far west as Bathurst in the summer of 1836 (he described himself as “certainly alive, but half roasted with the intense heat”), Charles Darwin rode back to Sydney and set sail again on the Beagle with crates of specimens and a jaundiced view (he never went to the city of Darwin; the site was named for him during a later Beaglevoyage, and only settled in 1869).

After stopovers in Tasmania and the port of Albany on the southwest coast of the continent, he admitted that Australia was “an admirable place to accumulate pounds & shillings,” but he could not feel comfortable there, knowing that half his fellow citizens were “somewhere between a petty rogue & (a) bloodthirsty villain.”

His verdict: “I leave your shores without sorrow or regret.”

Others on the Beagle were more open-minded: Darwin’s servant and specimen collector, Syms Covington, soon emigrated back to Sydney, where he thrived, gaining property, becoming a postmaster and running an inn.

The pair corresponded for years, and in 1852, Darwin admitted that, “I feel a great interest about Australia, and read every book I can get hold of.” A gold rush allowed the colony to prosper more than Darwin had ever imagined, and four years later he even told Covington he felt a touch of envy that he hadn’t settled there himself.

Although he was by then a wealthy, respected scientist, Darwin thought that Australia might offer his children a brighter future than “old burthened” Britain.

(He would eventually have five sons and three daughters who survived beyond infancy.) “Yours is a fine country,” he wrote Covington warmly, “and your children will see it a very great one.”

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that there is more than one place in North America to see the Wollemi pine.

Others on the Beagle were more open-minded: Darwin’s servant and specimen collector, Syms Covington, soon emigrated back to Sydney, where he thrived, gaining property, becoming a postmaster and running an inn.

The pair corresponded for years, and in 1852, Darwin admitted that, “I feel a great interest about Australia, and read every book I can get hold of.” A gold rush allowed the colony to prosper more than Darwin had ever imagined, and four years later he even told Covington he felt a touch of envy that he hadn’t settled there himself.

Although he was by then a wealthy, respected scientist, Darwin thought that Australia might offer his children a brighter future than “old burthened” Britain.

(He would eventually have five sons and three daughters who survived beyond infancy.) “Yours is a fine country,” he wrote Covington warmly, “and your children will see it a very great one.”

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that there is more than one place in North America to see the Wollemi pine.

Links :

Thursday, September 5, 2024

How will generative artificial intelligence transform the meteorological sector?

From Meteorological Technology Int by Jack Roper

Generative artificial intelligence could transform the meteorological sector if issues of data availability and accuracy, model trust and lack of transparency are overcome.

Like virtually every sector, meteorology may soon find itself transformed by generative artificial intelligence (GAI), a technology that UN secretary-general António Guterres believes has enormous potential for good and evil at scale.

Even before the advent of GAI, AI models have shown predictive capability competitive with numerical weather prediction (NWP).

“Physics-based forecast models take observations of the atmosphere’s current state then use our knowledge of physics to move them forward in time,” explains Kyle Hilburn, a research scientist at Colorado State University’s Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA).

“AI models learn from training data then use that learning, rather than physics, to move observations forward.”

Efforts to use machine learning to replace problematic parameterizations of subscale processes such as turbulence and cloud physics in NWP models date back to the 1990s.

But only in 2018 did Peter Dueben and Peter Bauer, who both work on Earth system modeling at the ECMWF, first posit the feasibility of entirely replacing NWP models with AI.

“From 2022 onward, big tech companies made breakthroughs in AI weather prediction and began sharing their findings,” says Dr Simon Driscoll, who researches AI weather and climate modeling at the University of Reading.

“The last two years have seen an explosion in AI models producing fast and accurate forecasts that rival and sometimes outperform NWP models.”

This wave of NWP-competitive AI models includes Google’s GraphCast, which uses machine learning in place of numerical physics to improve medium-range forecasts, and Nvidia’s FourCastNet model based on Fourier neural operators, a machine learning technique tailored to physical systems governed by partial differential equations.

“FourCastNet has proved as skilful as state-of-the-art NWP, but 10,000 to 100,000 times faster and more energy efficient,” says Nvidia’s director of accelerated computing products, Dion Harris.

“It enables generation of massive ensembles to more accurately characterize the probabilities of low-likelihood, high-impact events.

Its latest version uses spherical harmonics, making possible prediction over decades or even centuries.”

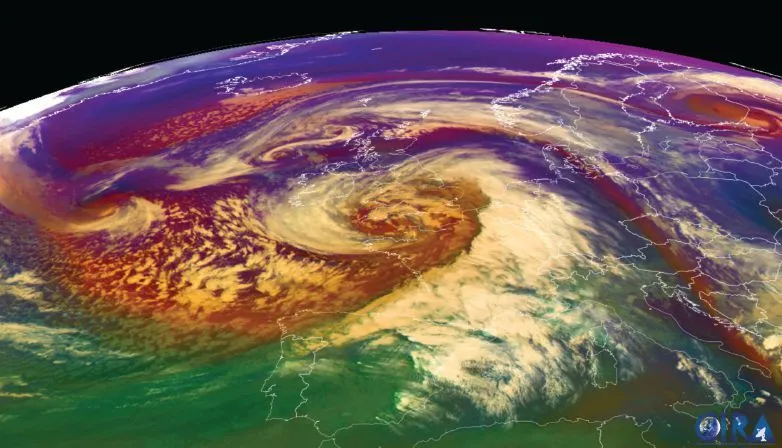

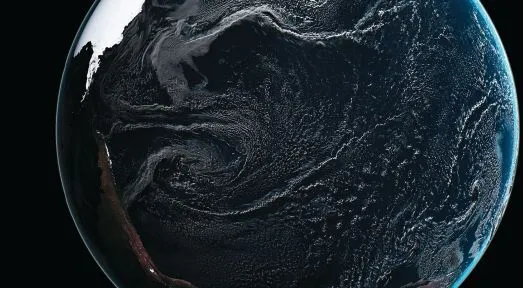

Imagery of Storm Ciarán from the Meteosat-10 satellite

Imagery of Storm Ciarán from the Meteosat-10 satelliteTesting, testing

University of Reading scientists tested the ability of AI models including GraphCast and FourCastNet to predict the development of Storm Ciarán, which brought death and disruption to northwestern Europe in late 2023.

The models were initialized with ECMWF data from an early stage in Ciarán’s development and tasked with replicating its evolution.

“The models were good at tracking the storm’s position and capturing variables such as mean sea-level pressures,” comments Driscoll.

“But they were less good at things we truly care about, such as peak gust speeds, which relate to damage.

It suggests that naïve use of these models could lead us to issue the wrong level of weather warning, resulting in insufficient precautions and increased loss of life,” he adds.

“Predictive AI outputs the most likely or average outcome over a range of possibilities, whereas GAI outputs one possible outcome”

Kyle Hilburn, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA), Colorado State University

Why AI models may under-represent extreme events is not definitively understood, but one factor may be the under-representation of such events in training data.

Classification algorithms are typically trained on data representing (for instance) cats and dogs in equal proportions, but storms like Ciarán are statistical outliers with fewer examples to learn from.

Another issue may be the metrics used to optimize models.

“Computer scientists optimize models using metrics such as mean-squared error, but a loss function based on the mean won’t be suited to capturing extremes,” comments CIRA’s Hilburn.

“We need to optimize for things meteorologists care about – and non-traditional, object-based metrics could provide better information about extreme events like storms and hurricanes.”

Emerging Gen AI models

Although the atmosphere is a continuous fluid, storms can be considered discrete objects with recognizable perimeters that can be tracked over time.

Optimizing models to track such objects, rather than mean accuracy, could improve their sensitivity to extreme events.

A new generation of models based on generative AI may equally solve the problem.

“GAI learns to generate new content from given inputs,” Nvidia’s Harris explains.

“It learns patterns and structures of entire distributions of data and generates new instances.

It can generate synthetic satellite images that are statistically indistinguishable from the true images it trained on,” he adds.

GAI is the technology behind large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, and can produce text, music or pictures that resemble human outputs in response to prompts.

Meteorologists distinguish generative AI from the predictive AI behind GraphCast and FourCastNet.

“Predictive AI outputs the most likely or average outcome over a range of possibilities, whereas GAI outputs one possible outcome,” explains Hilburn.

“The average may not be meaningful in relation to extreme events, or scenarios with two divergent possibilities.

GAI diffusion models, trained to remove noise from images and learn about underlying structures, seem to provide sharper, more realistic features than other types of AI.”

Predictive models respond to uncertainty with less specific predictions; GAI models choose one possibility to assemble into an outcome.

Repeating this process many times could create large ensembles to represent the probability of extreme events developing from a given atmospheric state.

This is the aim of Google’s Scalable Ensemble Envelope Diffusion Sampler (SEEDS) model.

“Current best practice in ensemble weather prediction is to run a weather model 30 to 50 times on a supercomputer with slightly different initial conditions,” explains Google research scientist Rob Carver.

“If it rains in 50% of those forecasts, the probability of rain is 50%.

By generating hundreds or thousands of forecasts in record time, GAI can model probability more accurately than the best traditional methods.”

By multiplying ensemble members showing the possible range of events in the next 3 to 10 days, SEEDS may improve the statistical accuracy of forecasts, enabling the likelihood of events like Storm Ciarán to be better assessed.

“We base the chance of a weather event on how many of our forecasts show it will happen, so more forecasts means greater accuracy.

Running traditional models takes hours or days.

SEEDS cuts that time by 90% and produces as many forecasts with 90% less computing power,” Carver adds.

The butterfly effect

Computational cost is a limiting factor for physics-based ensembles, as is the slowness of NWP models when end users need to know conditions in the next two hours.

Although expensive to train, GAI models cost little to run once trained and may produce forecasts in seconds rather than hours.

“Running traditional models takes hours or days.

SEEDS cuts that time by 90%.”

Rob Carver, Google

“GAI ensemble forecasts may be the next domain for tech companies,” says Driscoll.

“Because the atmosphere is chaotic, small perturbations in initial conditions lead to wildly divergent predictions after a few days.

GAI models can produce forecasts with an enormous number of initial conditions and sample initial uncertainty extremely quickly,” he adds.

Ensembles address the so-called butterfly effect, whereby small initial errors grow into large errors and cause the accuracy of weather models to deteriorate over time.

But questions remain as to whether GAI can truly decipher the inherent uncertainty of weather.

University of Reading scientists tested the ability of AI models including GraphCast and FourCastNet to predict the development of Storm Ciarán, which brought death and disruption to northwestern Europe in late 2023.

The models were initialized with ECMWF data from an early stage in Ciarán’s development and tasked with replicating its evolution.

“The models were good at tracking the storm’s position and capturing variables such as mean sea-level pressures,” comments Driscoll.

“But they were less good at things we truly care about, such as peak gust speeds, which relate to damage.

It suggests that naïve use of these models could lead us to issue the wrong level of weather warning, resulting in insufficient precautions and increased loss of life,” he adds.

“Predictive AI outputs the most likely or average outcome over a range of possibilities, whereas GAI outputs one possible outcome”

Kyle Hilburn, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA), Colorado State University

Why AI models may under-represent extreme events is not definitively understood, but one factor may be the under-representation of such events in training data.

Classification algorithms are typically trained on data representing (for instance) cats and dogs in equal proportions, but storms like Ciarán are statistical outliers with fewer examples to learn from.

Another issue may be the metrics used to optimize models.

“Computer scientists optimize models using metrics such as mean-squared error, but a loss function based on the mean won’t be suited to capturing extremes,” comments CIRA’s Hilburn.

“We need to optimize for things meteorologists care about – and non-traditional, object-based metrics could provide better information about extreme events like storms and hurricanes.”

Emerging Gen AI models

Although the atmosphere is a continuous fluid, storms can be considered discrete objects with recognizable perimeters that can be tracked over time.

Optimizing models to track such objects, rather than mean accuracy, could improve their sensitivity to extreme events.

A new generation of models based on generative AI may equally solve the problem.

“GAI learns to generate new content from given inputs,” Nvidia’s Harris explains.

“It learns patterns and structures of entire distributions of data and generates new instances.

It can generate synthetic satellite images that are statistically indistinguishable from the true images it trained on,” he adds.

GAI is the technology behind large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, and can produce text, music or pictures that resemble human outputs in response to prompts.

Meteorologists distinguish generative AI from the predictive AI behind GraphCast and FourCastNet.

“Predictive AI outputs the most likely or average outcome over a range of possibilities, whereas GAI outputs one possible outcome,” explains Hilburn.

“The average may not be meaningful in relation to extreme events, or scenarios with two divergent possibilities.

GAI diffusion models, trained to remove noise from images and learn about underlying structures, seem to provide sharper, more realistic features than other types of AI.”

Predictive models respond to uncertainty with less specific predictions; GAI models choose one possibility to assemble into an outcome.

Repeating this process many times could create large ensembles to represent the probability of extreme events developing from a given atmospheric state.

This is the aim of Google’s Scalable Ensemble Envelope Diffusion Sampler (SEEDS) model.

“Current best practice in ensemble weather prediction is to run a weather model 30 to 50 times on a supercomputer with slightly different initial conditions,” explains Google research scientist Rob Carver.

“If it rains in 50% of those forecasts, the probability of rain is 50%.

By generating hundreds or thousands of forecasts in record time, GAI can model probability more accurately than the best traditional methods.”

By multiplying ensemble members showing the possible range of events in the next 3 to 10 days, SEEDS may improve the statistical accuracy of forecasts, enabling the likelihood of events like Storm Ciarán to be better assessed.

“We base the chance of a weather event on how many of our forecasts show it will happen, so more forecasts means greater accuracy.

Running traditional models takes hours or days.

SEEDS cuts that time by 90% and produces as many forecasts with 90% less computing power,” Carver adds.

The butterfly effect

Computational cost is a limiting factor for physics-based ensembles, as is the slowness of NWP models when end users need to know conditions in the next two hours.

Although expensive to train, GAI models cost little to run once trained and may produce forecasts in seconds rather than hours.

“Running traditional models takes hours or days.

SEEDS cuts that time by 90%.”

Rob Carver, Google

“GAI ensemble forecasts may be the next domain for tech companies,” says Driscoll.

“Because the atmosphere is chaotic, small perturbations in initial conditions lead to wildly divergent predictions after a few days.

GAI models can produce forecasts with an enormous number of initial conditions and sample initial uncertainty extremely quickly,” he adds.

Ensembles address the so-called butterfly effect, whereby small initial errors grow into large errors and cause the accuracy of weather models to deteriorate over time.

But questions remain as to whether GAI can truly decipher the inherent uncertainty of weather.

Tomorrow.io’s Gale uses AI to synthesize millions of data points to provide concise weather summaries tailored to each business’s unique requirements

Tomorrow.io’s Gale uses AI to synthesize millions of data points to provide concise weather summaries tailored to each business’s unique requirements“It remains unclear whether GAI models really represent the butterfly effect,” says CIRA’s Hilburn.

“Where physics-based models show that error growth over time, GAI models seem to stick to the same solution as they’re integrated forward.

We can run huge GAI ensembles but if those models aren’t diverging, they may not predict the full range of possibilities.”

Since GAI and physics-based models exhibit different error characteristics, Hilburn foresees value in ensembles combining both model types.

Google’s SEEDS remains an internal research project today and further research must determine whether GAI can be relied on for actionable weather information.

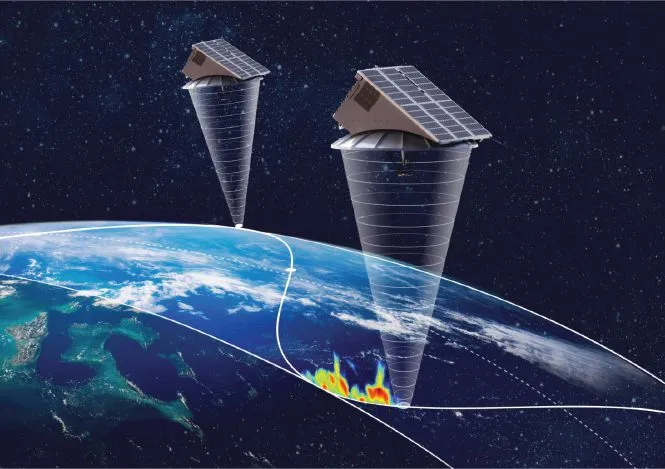

Tomorrow.io announced in 2023 that its pathfinder radar satellites, Tomorrow-R1 and Tomorrow-R2, successfully characterized precipitation intensity from space

Tomorrow.io announced in 2023 that its pathfinder radar satellites, Tomorrow-R1 and Tomorrow-R2, successfully characterized precipitation intensity from spaceBuilding trust

While meteorologists use their knowledge of physics to ascertain whether physics-based forecasts make sense, establishing trust in the inscrutable learning behind GAI predictions presents a different challenge.

“Explainable AI techniques can help users understand and trust AI outputs,” says Driscoll.

“Symbolic regression uses machine learning to search for mathematical expressions that make model outputs human-readable.

That reduces the black-box problem but is hard to apply to weather forecasts, given their complexity.”

“Explainable AI techniques can help users understand and trust AI output.”

Dr Simon Driscoll, University of Reading

GAI can also ‘hallucinate’ erroneous solutions – for example, when satellite imagery lacks sharp patterns or gradients pointing to any definite outcome.

Rather than admit to uncertainty, Hilburn says current models venture a potentially incorrect answer, providing an unsound basis for safety-critical decisions.

“Diagnostic tools could be used to filter out unphysical, grossly inaccurate or clearly impossible hallucinated predictions,” Harris suggests.

“Physics-derived ‘guardrails’ and techniques such as domain alignment could refine GAI to provide information better-suited to exact applications.”

Generally speaking, the predictive power of GAI models increases in proportion to the quantity and richness of training data.

Harris sees short supply of such data as the greatest single limitation on GAI forecasting capability today.

“High-quality, ultra-high-resolution data is not easily available in vast amounts,” he says.

“This data challenge requires us to fuse multiple, complementary sources of data and develop novel means of data augmentation, perhaps using synthetic data from physical models.”

Collaboration is essential

GAI presents well-publicized potential to replace human jobs in many sectors and may soon be writing articles such as this.

But rather than rendering meteorological observations obsolete, its thirst for training data will drive an increased demand for data.

Although it may transform how forecasts are made, realizing its potential demands cooperation between developers and meteorologists.

“For AI models to help humanity, we need transparency and reproducibility,” comments Hilburn.

“But private companies may not have an incentive to make models publicly available.

So far, evaluation has primarily been by AI developers themselves.

What developers think is important is not necessarily the same as what meteorologists think is important,” he adds.

GAI presents well-publicized potential to replace human jobs in many sectors and may soon be writing articles such as this.

But rather than rendering meteorological observations obsolete, its thirst for training data will drive an increased demand for data.

Although it may transform how forecasts are made, realizing its potential demands cooperation between developers and meteorologists.

“For AI models to help humanity, we need transparency and reproducibility,” comments Hilburn.

“But private companies may not have an incentive to make models publicly available.

So far, evaluation has primarily been by AI developers themselves.

What developers think is important is not necessarily the same as what meteorologists think is important,” he adds.

Tomorrow.io’s Resilience Platform

In the US, the AI Institute for Research on Trustworthy AI in Weather, Climate, and Coastal Oceanography (AI2ES) exists to bridge this gap between computer and climate science.

Meanwhile, the ECMWF demonstrates leadership in developing AI-based models alongside established, physics-based capabilities.

“The pace of development has left many institutes out of the loop,” says Driscoll.

“But the ECMWF has responded very quickly and already runs an AI model alongside operational forecasts, demonstrating that forecasting centers can keep up with the tech giants.”

GAI’s meteorological applications could include boosting ensembles, qualifying uncertainty and downscaling image resolution.

It also promises to improve resilience and decision making by distilling complex forecast information into concise and actionable summaries.

This is the aim of Gale, a GAI assistant available to customers of weather intelligence provider Tomorrow.io (see Developing an all-seeing radar constellation to advance Gen AI, page 12).

“Gale summarizes and condenses information in a readable, shareable way,” says Tomorrow.iogrowth and strategy VP Cole Swain.

“Where once we did data visualizations, chatting to Gale gets the answer you need right away.

Because it combines forecast information with our foundational understanding of an enterprise’s problems and protocols, it can say, ‘Hey, Jimmy – reschedule your rooftop solar installation on Tuesday because there’s gonna be heavy rain.’”

Valuable market insights

Rather than developing its own large language model, Tomorrow.io leverages third-party LLMs to enable Gale’s functionality.

Gale uses only one LLM per customer session, but switches between LLMs depending on the required workflow.

“Gale is model-agnostic,” says Swain.

“Some LLMs are better at logic, creating human-readable text or condensing vast amounts of information into something concise.

We have different arrows in our quiver – and our technical stack uses pre-programmed logic to put the right technology in our bow at the right time.”

Tomorrow.io’s customers use the company’s platform to make operational and safety-critical decisions, but their onboarding promotes an understanding that weather is hard to predict.

Gale is accompanied by a disclaimer stating that Tomorrow.io is not responsible for its outputs, and it is discouraged from offering potential hallucinations.

“Our core principle is never to allow the LLM to come up with information itself,” says Swain.

“We use it solely to translate, compress and organize technical, programmatic information into something legible.

Of course, we also take precautionary measures internal to our databases, to validate quality control and assurance.”

Many Tomorrow.io users have embraced Gale.

Following a productive discovery phase, it is in use with selected customers, though the company is mindful to avoid displacing what works by forcing adoption on everyone.

Already, Gale is providing valuable market insights.

“Understanding what customers want is the holy grail of product management,” says Swain.

“Because customers ask Gale questions, we see exactly what they want from our platform.

That understanding of value both accelerates and removes risk from our strategic decisions.”

“Understanding what customers want is the holy grail of product management.”

Cole Swain, Tomorrow.io

The pace of AI revolution is unfamiliar to conventional academic research, with breakthroughs expected to continue at breakneck speed as advances like the Nvidia Grace Hopper AI chip enable bigger models capable of faster data exchange.

“We expect AI to become integrated across the pipeline of operational meteorology, in data fusion, data assimilation, forecasting, post-processing and meaningful, easy-to-understand textual and visual descriptions of weather,” Nvidia’s Harris adds.

“Its potential to enhance meteorological outputs in previously unimaginable ways will be best realized collaboratively, with expert meteorologists in the loop,” he concludes.

Developing an all-seeing radar constellation to advance Gen AI

Tomorrow.io works to build weather resiliency programs with a customer base of hundreds of enterprises and governments worldwide.

Energy companies and airports upload their assets, field staff and schedules onto Tomorrow.io’s cloud-native Software as a Service platform and build protocols to navigate different weather events.

“We predict the intersection of weather with your operations,” says Tomorrow.io’s Cole Swain.

“Instead of just a forecast, we communicate who needs to do what to navigate the problem.”

The company was conceived when its founders devised novel means to infer weather observations from the attenuation of microwave signals and began providing forecasts by aggregating data from government models and sensors worldwide.

“We eventually realized the only way to truly disrupt the industry was to go into space,” Swain recalls.

“Where 90% of the world has no radar coverage today, our own constellation of satellites will provide full global coverage.”

Combined with models, this all-seeing radar constellation will improve the predictions Tomorrow.ioprovides to customers while creating a global dataset valuable in advancing GAI applications in weather and climate.

“Everything in AI is about the inputs,” explains Swain.

“What good is a forecast model if you don’t know the initial conditions? We need observations to train, calibrate and bias-correct AI over time.

That’s where our satellites, providing full atmospheric profiling of every location on Earth at 60-minute intervals, become important to the meteorological industry,” he adds.

The Gale interactive GAI assistant already enables Tomorrow.io users to derive succinct and shareable insights from complex weather reports (see main article).

“Historically, weather is an oratory field,” says Swain.

“People are used to watching the weatherman or reading text-based forecasts.

Now, GAI can summarize how that forecast impacts a user’s operations and they can ask questions about it.

“Across networks with hundreds of locations and thousands of employees, weather events happen every single day,” he continues.

“GAI expedites the ability to respond, telling you where on the network to focus attention and what you need to do next.”

Digital visualization of Nvidia’s Earth-2 software, which will simulate the planet’s climate

Improving the resolution and precision of forecasts

Generative AI can synthesize ultra-high-resolution images by learning the mapping between low-and higher-resolution images – a process called super-resolution in computer science and downscaling in meteorology.

CorrDiff is an Nvidia model that downscales coarse weather data.

“CorrDiff combines a correction model (Corr) and a diffusion model (Diff) to bias-correct and downscale a low-resolution forecast,” explains Nvidia’s Dion Harris.

“It draws on the well-established technique of Reynolds decomposition in fluid dynamics.”

Learn how NVIDIA's CorrDiff model is transforming weather prediction using #GenerativeAI ☀️➡️ https://t.co/LxcsADOFZm

— NVIDIA AI (@NVIDIAAI) July 15, 2024

With extreme weather expected to have more severe impacts on nations worldwide, CorrDiff is helping through #energyefficient high-resolution forecasts.🌦️ pic.twitter.com/bvUtwFwrpW

While CorrDiff’s chief purpose is improving the precision and fidelity of forecasts, it also lends itself to infilling or inpainting, data assimilation and synthetic data generation.

Nvidia has proved the concept over a region of Taiwan and the surrounding ocean.

“By training on radar-assimilated Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) data and ECMWF reanalyses, we achieved a 12.5 times increase from 25m to 2km resolution,” Harris reveals.

“CorrDiff generates samples at 2km resolution 1,000 times faster and 3,000 times more energy-efficiently than the WRF numerical weather prediction (NWP) model.

It can also synthesize fields of interest not present in the model inputs, such as radar reflectivity, opening the door to applications like impact assessment.”

Nvidia’s Earth-2 program aims to build the technologies and platforms needed to create digital twins of Earth for weather and climate applications.

Its ultimate goals are twofold: to advance understanding of climate change impacts on hyper-local scales and provide the reliable, actionable information needed to address them.

“Ever-higher-resolution weather and climate data is critically needed in planning for the disastrous consequences of climate change,” adds Harris.

“But simulating our planet at scales of tens of meters with NWP models is computationally very intensive.

By providing 12.5x resolution enhancements 3,000 times more efficiently, CorrDiff represents a major step toward the goals of Earth-2.”

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Are weather forecasts better with artificial intelligence?

Wednesday, September 4, 2024

The US Navy is going all in on Starlink

Starlink in the night sky over the Greek island of Amorgos in 2022.

Photo: Fabien Pallueau; Getty

From Wired by Jared Keller

Life aboard a US Navy warship at sea can be stressful, boring, and lonely, with separation from friends and family and long stretches between port calls both isolating and monotonous.

Now, Elon Musk is here to take the edge off.

In a now deleted press release from the Naval Information Warfare Systems Command (NAVWAR), the Navy recently announced that it is experimenting with bringing reliable and persistent high-speed internet to its surface warships.

The connectivity comes via a new system developed under its Sailor Edge Afloat and Ashore (SEA2) initiative, which uses satellites from the Starlink network maintained by Musk’s SpaceX and other spaceborne broadband internet providers to maintain a constant and consistent internet connection for sailors—a system that NAVWAR says has “applications across the entire Navy.”

The US Defense Department has for decades relied on a network of aging satellites to furnish service members at sea with decidedly slow internet access, according to an updated release NAVWAR shared with WIRED.

By contrast, commercial satellite constellations like Starlink and Eutelsat OneWeb, which number in the thousands and offer coverage from a significantly lower orbit, provide a far superior connection.

The resulting SEA2 system, dubbed the Satellite Terminal (transportable) Non-Geostationary (STtNG), allows a warship’s tactical feeds secure access to low-orbit satellites with a median connection speed of 30 to 50 megabits per second, according to NAVWAR.

With the installation of additional Starlink antennas, the system can scale up to speeds of 1 gigabit per second.

NAVWAR said that it scrubbed its initial press release, which showed the installation of a Starlink terminal aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, from the Pentagon’s Defense Visual Information Distribution System (DVIDS) media portal to “address inaccuracies and ensure the information is correct,” Elisha Gamboa, a command spokesperson, told WIRED in a statement.

News of the Starlink terminal’s installation aboard the Lincoln in particular came as the aircraft carrier and its associated battle group were redirected to the US Central Command area of operations in the Middle East amid increased tensions between Israel and Iran following the former’s targeted killing of a Hamas leader in Tehran.

The Navy has not yet disclosed how many surface warships have received Starlink terminals.

Defense officials told DefenseScoop in April that the DOD was at the time evaluating the system aboard two deployed vessels “with aims to field those broadband-providing capabilities across a fleet of up to 200 in the future.”

Originally a “passion project” of Lincoln combat systems officer Commander Kevin White, SEA2 systems were first installed aboard the next-generation aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford in February 2023, offering sailors the ability to quickly and easily communicate with loved ones back home no matter where they are in the world—a major boost to morale amid the doldrums of life at sea.

The system even allowed hundreds of sailors to enjoy a live broadcast of Super Bowl LVIII through a normal TV streaming service aboard the warship this past year.

“Having the ability to reach out to friends or family allows our sailors the opportunity to decompress for a few minutes, and that in turn allows them to be able to operate more efficiently,” Richard Haninger, the Ford’s deployed resiliency educator, said following the installation of the SEA2 system aboard the carrier in February 2023.

“It’s not just about reaching back to friends and family, the ability to pay a bill online, take an online class, or even just check the score of the game [...] all of this allows our Sailors the chance to access something that lowers their stress level, then return to work after a quick break more focused and able to complete the mission.”

But beyond morale-boosting applications, SEA2 also purportedly offers major benefits for “tactical and business applications” used by sailors on a daily basis, like, say, those used for air wing maintenance or for tracking pay and benefits.

As White explained in a May release from the Navy on the initiative, most of these applications function at higher classification levels and are encrypted, but they’re still designed to operate on the commercial internet without jeopardizing information security.

“The fact that we’re not making use of that opportunity with modern technology to allow classified tactical applications to ride the commercial internet is where we are missing out, so we built [SEA2] to be able to do that in the future,” as White put it.

“We’re close to demonstrating a couple of those applications, and I am fully confident it will be game changing.” (As of June, the Navy had not authorized the use of classified data with the system)

The Navy also expects to see broad “tangible warfighting impact” from the proliferation of SEA2 across the surface fleet, namely on “recruitment and retention, mental health, cloud services, and work stoppages due to slow and inaccessible websites,” as one service official told DefenseScoop in April.

Sailors work inside USS Abraham Lincoln‘s Carrier Air Traffic Control Center (CATTC). DOD

The US Space Force signed a $70 million contract with Starlink parent company SpaceX in October 2023 to provide “a best effort and global subscription for various land, maritime, stationary and mobility platforms and users” using Starshield, the company’s name for its military products.

The US Army currently remains reliant on Starlink, but the service has been casting about for fresh commercial satellite constellations to tap into for advanced command and control functions, according to Defense News.

And SpaceX is actively building a network of “hundreds” of specialized Starshield spy satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office, Reuters reported earlier this year.

But Starlink is far from a perfect system, especially for potential military applications.

According to a technical report obtained by The Debrief, Ukraine has claimed that Russia’s military intelligence agency has conducted “large-scale cyberattacks” to access data from the Starlink satellite constellations that have proven essential to the former’s military communications infrastructure since the start of the Russian invasion in 2022.

Indeed, significant hardware vulnerabilities have imperiled Starlink terminals at the hands of experienced hackers, as WIRED has previously documented.

More importantly, there’s the matter of Musk’s ownership of Starlink.

The controversial SpaceX founder had previously refused to allow Ukraine to use the satellite constellation to launch a surprise attack against Russian forces in Kremlin-controlled Crimea in September 2022, prompting concerns among Pentagon decisionmakers that a private citizen with a questionable perception of geopolitics could drastically shape US military operations during a future conflict simply by switching off service branches’ Starlink access, according to an Associated Press report last year.

“Living in the world we live in, in which Elon runs this company and it is a private business under his control, we are living off his good graces,” a Pentagon official told The New Yorker in August 2023.

“That sucks.”

Given these potential risks, it’s unlikely that Starlink will see deeper integration into the major tactical systems that govern the operation of a Navy warship at sea.

But for the moment, it looks as though sailors will at least get a welcome reprieve from the stress and solitude of life on the high seas.

Links :

- PC Mag : US Navy Eyes Adopting SpaceX's Starlink Across Its Fleet

- TheWarZone : Starlink Now Being Deployed On U.S. Navy Warships

- Benzinga : US Navy Installs Starlink On USS Abraham Lincoln Aircraft Carrier, Currently In The Middle East: 'A Super Bowl Watch Party Was Held Live, Which Had Never Been Done Before'

- Interesting Engineering : US Nvay could get 20x faster internet connectivity using Starlink satellite

- NavalNews : New Russian Navy ‘Murena’ Maritime Drone Shown With Possible Starlink

- NavyTimes : How Navy chiefs conspired to get themselves illegal warship Wi-Fi

- GeoGarage blog : A whole new orbit: why shipping should embrace ... / Want internet service on your yacht? It'll run you ... / Starlink's marine satellite system opens up new, speedy ...

Tuesday, September 3, 2024

New seamount and previously unknown species discovered in high priority area for international marine protection

From toadfish and amphipods to a vivid siphonophores, the underwater mountains comprising the Nazca and Salas y Gómez Ridges host amazingly diverse life forms.

The majority of both ridges lie outside of any country’s jurisdiction — in the high seas — leaving these distinctive and understudied ecosystems vulnerable to human exploitation from climate change, plastic pollution, overfishing, and potential deep-sea mining.

Many experts in marine protection and policy believe that the Nazca and Salas y Gómez Ridges are a top priority for designation as one of the world’s first high-seas marine protected areas.

Recent Schmidt Ocean Institute-supported expeditions to the region discovered over 150 suspected new species and several new seamounts.

To expand on these expeditions’ success and contribute vital data to inform future protections of these high seas areas, the #NazcaHighSeas expedition brought an international team of scientists to map and characterize the biodiversity in the area.

Here are some of the amazing scenes documented this expedition in the high seas off the coast of South America.

From SchmidtOcean

A team of oceanographers led by Schmidt Ocean Institute have discovered and mapped a new seamount on the Nazca Ridge in international waters, 900 miles off the coast of Chile.

The Nazca Ridge, an underwater mountain chain, along with the adjoining Salas y Gómez Ridge, is one of several global locations under consideration for designation as a high seas marine protected area.

Tomer Ketter has been fascinated by maps since his early days of exploring with his father.

Today, he is co-chief scientist of the NazcaHighSeas expedition, leading a team of international scientists to explore lush underwater habitats that were largely unmapped and understudied — until now.

The team has collected valuable hydrographic and oceanographic data and they have observed breathtaking wildlife along the Nazca and Salas y Gómez Ridges in the high seas.

Their work could provide the data needed to establish protections in these essential areas of our global ocean.

The seamount discovery is one of many from a 28-day expedition to the international waters of the Nazca Ridge led by Schmidt Ocean Institute in partnership with Ocean Census and the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center at the University of New Hampshire.

During this expedition, the science department discovered, mapped, and explored a new seamount with Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) SuBastian.

The seamount covers an area of about 70 sq km.

The summit depth is 994m and the base is at 4,103m giving it a prominence of 3,109m over the surrounding seafloor.

Hydrographic experts used the Research Vessel Falkor (too)‘s EM124 multibeam echosounder to map the seamount, located 700 nautical miles west of Chile in international waters.

The ship’s crew has proposed a name currently under review with the GEBCO Subcommittee on Underwater Feature Names.

Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

The seamount covers an area of about 70 sq km.

The summit depth is 994m and the base is at 4,103m giving it a prominence of 3,109m over the surrounding seafloor.

Hydrographic experts used the Research Vessel Falkor (too)‘s EM124 multibeam echosounder to map the seamount, located 700 nautical miles west of Chile in international waters.

The ship’s crew has proposed a name currently under review with the GEBCO Subcommittee on Underwater Feature Names.

Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

The newly discovered underwater mountain is over 1.9 miles (3109 meters) tall and supports a thriving deep-sea ecosystem.

In addition to mapping the seamount, the team conducted an exploratory dive with an underwater robot on one of the mountain’s ridges, finding sponge gardens and ancient corals.

This expedition is special because it is the first one led entirely by Schmidt Ocean Institute staff.

While we normally support visiting scientists and partners from outside organizations, this time, the science department on the ship and staff on shore are coordinating all aspects of this research along the Nazca and Salas y Gómez Ridges in the high seas.

These diverse and understudied ecosystems are vulnerable to human exploitation from climate change, plastic pollution, overfishing, and potential deep-sea mining.

Many experts in marine protection and policy believe that these ridges are a top priority for designation as one of the world’s first high-seas marine protected areas.

The NazcaHighSeas expedition builds upon the thrilling discoveries made by international scientists working in the region since January 2024, and it will establish a scientifically rich baseline that will help advance informed high seas protections.

The team mapped and explored nine additional unprotected features on this Southeast Pacific underwater mountain range.

One of the mountains harbors a pristine coral garden consisting of deep-sea corals that provide shelter for an array of organisms such as rockfish, brittle stars, and king crabs.

With an area of approximately 800 square meters, this coral garden is about the size of three tennis courts.

One of the mountains harbors a pristine coral garden consisting of deep-sea corals that provide shelter for an array of organisms such as rockfish, brittle stars, and king crabs.

With an area of approximately 800 square meters, this coral garden is about the size of three tennis courts.

During a 40-day research expedition along the Salas y Gómez Ridge, an underwater mountain range that extends from Chile to Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, an international team of scientists observed individual seamounts harboring distinct ecosystems like glass sponge gardens and deep coral reefs.

These distinct habitats provide homes for awe-inspiring deep-sea creatures — octopus, squid, fish, corals, mollusks, sea stars, sea urchins, crabs, squat lobsters, and more.

Many of these animal sightings could be species new to science or an expansion of the known range.

Experts hope their robust findings will advance efforts to establish high-seas protected area designation for this biologically rich region.

Beyond mapping seamounts to high resolution and conducting ROV surveys, the team captured the first camera footage of a live Promachoteuthis squid, a genus that is so rare that only three species have been described based on only a few collected specimens, several of which are from the late 1800s.

Until now, the squid genus has only been characterized from dead samples found in nets.

They also documented a Casper octopus, the first time this species has been seen in the Southern Pacific.

Two rare Bathyphysa siphonophores, commonly known as flying spaghetti monsters, were also seen during the expedition.

Until now, the squid genus has only been characterized from dead samples found in nets.

They also documented a Casper octopus, the first time this species has been seen in the Southern Pacific.

Two rare Bathyphysa siphonophores, commonly known as flying spaghetti monsters, were also seen during the expedition.

This is the first footage of a live Promachoteuthis squid.

Until now, the squid genus has only been characterized from dead samples found in nets.

The squid was documented on Dive 693, while exploring an unnamed seamount (internally designated as T06) along the Nazca Ridge, off the coast of Chile.

Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean InstituteROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Until now, the squid genus has only been characterized from dead samples found in nets.

The squid was documented on Dive 693, while exploring an unnamed seamount (internally designated as T06) along the Nazca Ridge, off the coast of Chile.

Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean InstituteROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

“Upon concluding our third expedition to the region, we’ve explored around 25 seamounts on the Nazca and Salas y Gómez Ridges,” said Co-Chief Scientist and Schmidt Ocean Institute Marine Technician, Tomer Ketter.

“Our findings highlight the remarkable diversity of these ecosystems, while simultaneously revealing the gaps in our understanding of how the seamount ecosystems are interconnected.

We hope the data gathered from these expeditions will help inform future policies, safeguarding these pristine environments for future generations.”

Since January 2024, Schmidt Ocean Institute has supported several scientific explorations, including the most recent NazcaHighSeas expedition, to study biodiversity and oceanographic conditions along the Nazca, Salas y Gómez, and Juan Fernandez Ridges.

International scientists have used the technology and expertise available on the Research Vessel Falkor (too) for data collection and a scientific examination of this essential area in our global Ocean.

These underwater mountains harbor remarkable biodiversity, and the data gathered during our time here will help establish the baseline scientific knowledge needed to inform conservation and protection efforts, which many experts believe is critical to the overall health of the Ocean and the planet.

The expedition was the third exploration this year of the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges conducted on the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor (too).

Two previous expeditions in January and February documented over 150 previously unknown species and numerous range extensions for animals not previously known to live on the ridge.

An additional 20 suspected new species were collected during this expedition.

Two previous expeditions in January and February documented over 150 previously unknown species and numerous range extensions for animals not previously known to live on the ridge.

An additional 20 suspected new species were collected during this expedition.

Marine Technician and Expedition Co-Chief Scientist Tomer Ketter, supervises Mission Control room monitors, together with ROV Supervisor Michael Rae, and Erin E.

Marine Technician and Expedition Co-Chief Scientist Tomer Ketter, supervises Mission Control room monitors, together with ROV Supervisor Michael Rae, and Erin E.Easton, Assistant Professor in the School of Earth, Environmental, and Marine Sciences at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley – UTRGV.

Credit: Misha Vallejo Prut / Schmidt Ocean InstituteMisha Vallejo Prut / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Prior to Schmidt Ocean Institute’s expeditions this year, 1,019 species were known to live in this portion of the Pacific Ocean.

The number now exceeds 1,300 and is growing.

The records will be sent to the Ocean Census, an international, collaborative alliance led by the Nippon Foundation and Nekton to accelerate the discovery and protection of ocean life.

“The seamounts of the Southeastern Pacific host remarkable biological diversity, with species found nowhere else to date,” said Prof.

Alex David Rogers, Science Director of Ocean Census, “The work our taxonomists have conducted aboard Falkor (too), supported by Schmidt Ocean Institute team, will significantly enhance our understanding of the distribution of remarkable life forms on these underwater mountains, including several that have never before been mapped or seen by human eyes.”

Alex David Rogers, Science Director of Ocean Census, “The work our taxonomists have conducted aboard Falkor (too), supported by Schmidt Ocean Institute team, will significantly enhance our understanding of the distribution of remarkable life forms on these underwater mountains, including several that have never before been mapped or seen by human eyes.”

A large bamboo coral holding benthic ctenophores, barnacles, a sea star, and ophiuroids was documented on Dive 696 while exploring a newly discovered and mapped seamount, cataloged as KW-14176, along the Nazca Ridge off the coast of Chile.

Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean InstituteROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean InstituteROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

High-resolution mapping was conducted by a team of hydrographers who graduated from the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center at the University of New Hampshire.

The seafloor data will be included in the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project and will contribute to international understanding and management of Nazca and Salas y Gómez.