Saturday, October 24, 2020

Why measure wind?

Friday, October 23, 2020

COVID-inspired adventure takes amateur sailors from Sunshine Coast to Great Keppel on 'floating deckchair'

From ABC by Kylie Bartholomew

Holed up during COVID-19 restrictions in Queensland, amid an endless cycle of "wake up, check the phone, work, eat, sleep, repeat", Mike Swaine hatched a plan to escape.

The Sunshine Coast adventurer and his mate Joel decided to bunnyhop their way 300 nautical miles up the Queensland coastline from the Sunshine Coast to Great Keppel Island on a 17-foot Hobie Cat.

"I probably wouldn't have done it if COVID-19 hadn't hit," Mr Swaine said.

Over six days the two men were at the mercy of Mother Nature — at times nearly capsizing in brutal, 30-knot gusts with fully sheeted sails to zero wind and a dead motor in the dark.

"And you know, out in this little floating deckchair, that far out at sea is pretty sketchy," Mr Swaine said.

Powered primarily by wind, with no quarters below deck, riding on a Hobie Cat means feeling every wave and movement of the ocean.

The small catamaran was a somewhat unusual choice of vessel for such a long, multi-day journey, but with international and interstate travel off the cards, Mr Swaine wanted to find a new way to explore his home state.

"We're so lucky up here in Queensland that we still have a freedom in so many ways," he said.

"And we took advantage of that and our little catamaran got us to see our beautiful coastline."

An escape from lockdown

Swaine (L) with mate Joel Schulz, says the vessel's name, 'Betsy — the Ruby Princess', was a tribute to his grandmother — and the pandemic.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)

Swaine (L) with mate Joel Schulz, says the vessel's name, 'Betsy — the Ruby Princess', was a tribute to his grandmother — and the pandemic.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)Mr Swaine is an aerial photographer by trade but when the pandemic hit, his interstate travel was ground to a halt.

Seeking an escape, he embarked on lengthy YouTube binge sessions — watching marine adventurers from around the world.

It was in those binge sessions that the idea for his own Hobie Cat adventure was born.

Travel restrictions as a result of COVID-19 left aerial photographer Mike Swaine with more time to ponder other types of adventures.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)

Travel restrictions as a result of COVID-19 left aerial photographer Mike Swaine with more time to ponder other types of adventures.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)Experienced on the water, but not a sailor, Mr Swaine put plans in motion to sail the 17-foot Hobie Cat from south-east to central Queensland.

His mate Joel Schulz, aka the 'Coastal Cowboy', needed no convincing to be his right-hand man.

'Betsy the Ruby Princess'

The amateurs equipped themselves with sailing information via YouTube videos and gathered the necessary safety equipment.

"We didn't take that lightly and we didn't take having to get rescue services lightly," Mr Swaine said.

"We had three EPIRBs [Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons] and we had radios and we had contingency plans in place."

With the bare essentials on board, they set sail on 'Betsy, the Ruby Princess' — named out of "respect" of the pandemic.

Stuck in the dark to frolicking dolphins

They hoped for idyllic conditions but at times feared for their lives.

"There was, at one point, a Big Woody Island and in between Fraser Island and Hervey Bay when the boat turned into the wind [30 knot gusts] and the waves started coming over, we had no methodology of power and we had to try and jibe the boat," Mr Swaine said.

"We couldn't pull the jib out to turn the boat around because the wind was so strong, but as soon as we turn beam onto the wind, the boat would capsize.

"That was a point where there's a split second you're like, 'Man this is actually really serious, we have to take this seriously, we have to respect the ocean'."

As they headed north, the wind not only eased but stopped completely as they approached Bustard Head at dusk.

Mr Swaine said it was a "scary experience", exacerbated when Mr Schulz accidentally dropping the anchor overboard — without a line attached.

"So we're like, 'OK', we had a little two-horsepower motor, we fired up the motor, and then the motor went for a while — then the motor stops," Mr Swaine said.

"There's some rocky shoals where the waves are breaking, it was biggish surf by that stage, it'd dropped a little bit.

"But it was very uncomfortable and floating around in this little boat in the dark, it was a scary experience."

But then there was the flip side — being able to pull into any beach, seeing the moon and sun rise each day and the joy of watching dolphins and whales dance around the boat.

Swaine says pulling up to any beach for the night was a highlight of the trip.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)

Swaine says pulling up to any beach for the night was a highlight of the trip.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)"We had a whole heap of dolphins come up and start jumping around the boat," Mr Swaine said.

"One came right up next to the boat and was just looking at us.

"It was inquisitive, trying to trying to figure out what what these two idiots are doing, not quite the middle of the ocean but, a long way out at sea on a little Hobie Cat."

A 'magical place'

Mr Swaine said staying calm — with a sense of humour — enabled the pair to make good decisions and arrive at their destination safely.

"We came on the inside of Great Keppel and all of a sudden the wind stopped, the swell stopped and it was just this magical place," he said.

"We pulled up and this guy came down and he's like, 'Oh, where are you from?' and we said 'the Sunshine Coast' and he just thought we're all having a joke.

"He was really surprised. I think we were equally surprised that we actually made it."

Mr Swaine said that the expedition took its toll.

"[It was] hard on the body, I have blistered lips and hands, constant fear in your mind — particularly on a stretch with land barely visible but [it was] totally, absolutely worth it," he said.

After capturing most of the Australian coastline from the air, Swaine wanted to explore on the ground.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)

After capturing most of the Australian coastline from the air, Swaine wanted to explore on the ground.(Supplied: Mike Swaine)Mr Swaine said after capturing the coastline from the air for nearly 20 years, being able to experience it at ground level lived up to his expectation.

"People would travel all over the world to go to beautiful places," Mr Swaine said.

"We live in the most beautiful place in the world whether it's on the Sunny Coast or whether it's the entire coast — COVID-19 has given us an opportunity to explore our coastline."

Links :

- ABC : Meet the families trading winter for Fiji's sunny shores despite coronavirus / 'We are like coronavirus refugees': Sailors happy to be stranded in Tasmania / A tale of two yachts: Sailors in SE Asia make different pandemic choices

Thursday, October 22, 2020

Cat and mouse on the high seas: on the trail of China's vast squid fleet

From BBC Dan Collyns on the Pacific Ocean

Huge foreign fleets gather 400 miles off South America’s Pacific coast attracted by giant squid.

Peru’s coastguard must defend its territorial waters amid rising tension

The ocean is as black as chipped obsidian, yet whichever way you look dozens of bright lights illuminate the water and the night sky.

Nearly 400 nautical miles from the South American mainland, the crew of a Peruvian coastguard ship count more than 30 Chinese squid boats lighting up the sea like a city at night.

Some of the boats shine luminous green, others glow blinding white like an alien spacecraft in a movie.

Rigged along each side of the ships, incandescent lamps attract giant squid near the surface, where they can be hauled from the ocean by long metal arms jutting over the water.

The coastguard cutter Río Cañete drifts within 100 metres of a squid jigger, and the men on each boat gaze at each other across the water.

The Chinese fishermen work in silence; the crew of the Peruvian boat is also hushed – none of them has witnessed such a scene before.

“This is just part of a considerable fleet off our coastal waters,” says Commander Eduardo Atkins, looking out from the bridge of the 55-metre patrol boat.

“They’ve always been off our coasts, from Ecuador to Argentina, [but ] this time there’s been more media attention and the public feel affected.

Our job is to dissuade them from entering our maritime domain.”

Hawkeye 360, a radio frequency data analytics firm, reported that boats were “going dark” by switching off their AIS satellite tracking and entering the islands’ exclusive economic zone.

“We found multiple examples of maritime radio frequency activity that is within the Galápagos exclusive economic zone adjacent to the Chinese fleet,” said HawkEye 360’s CEO, John Serafini.

“These signals don’t align with any AIS tracking. Although the activity could represent legitimate vessels, at the very least it is suspicious behaviour,” he said.

The hunt for Han Feng 806

Commander Atkins steered the cutter south-west directly towards the cluster of Chinese vessels.

“We can clearly see the name of the ship Hangong Yu 303,” he said into a radiotelephone, reading out its coordinates on the ship’s bridge.

Then it came into view: the Hangong Yu 303 was a large red oil tanker, and it was refueling a smaller squid jigger, pipes connecting the two across the waves.

Atkins dispatched coastguard officers in one of the cutter’s two RIBs (rigid inflatable boat) to get a closer look, but the fishing boat quickly disconnected from the tanker and headed off in the other direction.

The Chinese ships regularly refuel on the open ocean in order to extend their voyage as long as possible, said Atkins.

“It’s not illegal but it’s considered bad practice,” he added through his white Covid face mask.

“They can be here for months and months, possibly changing their crews, but the boats remain here in the South Pacific.”

After more than 30 years with the coastguard, he could not hide his unease at the scale of the Chinese presence in the South Pacific, which has grown by roughly four times in nine years, according to Global Fishing Watch.

“They have factory boats which process the catch and the product arrives packaged and ready to eat in China,” he said.

It was one of these mother ships that Atkins wanted to find.

He could see Han Feng 806, a refrigerated container ship, or reefer, on the radar to the south-west but as he turned the cutter to give chase, the factory ship steered a course further out to sea.

Han Feng 806 stayed just out of reach.

The following day, Atkins changed course, steering east and then north, along the the 200-nautical mile limit of Peruvian waters.

The cutter’s twin 800 horsepower engines powered it smoothly along with the Humboldt current which swells up from Antarctica bringing nutrient-rich cold water along the coasts of Chile and Peru.

But there is genuine concern among local fishing associations that China’s harvesting of the Humboldt squid will inevitably hurt Peru’s fishery exports, of which the squid accounts for 43%.

“It’s an open secret that every year vessels mainly from China … come just at the edge of the 200-mile mark off Peru to extract this resource,” said Cayetana Aljovín, president of Peru’s National Fishing Society.

While South American countries impose quotas on their Humboldt squid catches, there are no limits on vessels in international waters.

About 800,000 tonnes of the fast-growing, highly migratory species are caught annually.

Overfishing of the squid could have an impact across the eastern Pacific, said Gustavo Sánchez, a marine biologist studying the species with Japan’s Hiroshima University.

A sperm whale spouted and then breached just two hundred metres from the ship, lifting spirits among the crew.

Hours passed uneventfully before an officer with binoculars spotted something on the starboard bow.

A mechanical arm lowered the eight-man RIB off the stern and armed coastguards climbed down to it from a rope ladder, ready to inspect the suspect craft.

The eight-metre Rosario had been drifting for two days with a broken outboard motor.

But what shocked the coastguard officers was the Rosario’s catch: hidden in nets stowed on the deck were four dead common dolphins, including one infant, and six sharks.

Despite the mask over his face, it was clear that the skipper, Juan Ramos, knew he had been caught red-handed.

Catching dolphins and selling their meat is illegal in Peru, but butchered porpoises are used as shark bait or sold as a delicacy known as muchame or chancho del mar on the black market.

“Unfortunately we caught a few dolphins but that was not my intention,” Ramos, 52, said.

“If the motor was in good condition I would have got them out [of the net],” he insisted.

But the coastguards doubted his story: someone had cut the tail fins from two of the dolphins to stop them breaking out of the net.

Junior officer Nicolás Castro asked Ramos for his permits and port departure documents, but he had none.

Despite their predicament, Ramos, an old sea dog, said if they hoisted a sail they would be back in Ancón, their port of departure, in 12 days.

He said small-scale fishermen could not compete.

Matt Bjerregaard, a specialist in marine biodiversity and fisheries, said climate change is forcing artisanal fishermen to follow the fish into deeper water, further from shore.

But large foreign fishing fleets are also to blame, he said, forcing fishermen “to search for new fishing areas, take longer to find their catch and, in turn, this has a negative impact on their livelihoods”.

Despite the seizure, the boat’s net was still cast – and some 50 metres away a sea lion struggled to free itself.

“Come on, come on, you’ll be free soon,” said Castro, leaning over the bow to cut the green mesh as the sea lion bit furiously at a yellow float.

“Go, go, be free, be free!” shouted Castro, brimming with emotion and trembling from the physical effort.

It was an emotional end to the encounter.

The fishermen and their illegal catch were taken back to the Río Cañete to be taken to the harbour master’s office in port and probably fined; their catch would be examined by experts from the fishing ministry.

The Rosario and its broken motor was left adrift on the ocean.

Meanwhile, the controversial Chinese fleet continued to move south, prompting Chile to announce that its navy would monitor its movements.

“What began as an arrest for an illegal act became a search and rescue operation,” said Atkins – pleased the mission had a satisfactory ending, but perhaps frustrated that he had to be content with the small fry while the big fish got away.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : 'It's terrifying': can anyone stop China's vast armada of fishing ...

- DW : Pakistan: China's 'involvement' in deep sea fishing angers local fishermen

- Maritime Executive : How NGOs Can Help Keep Tabs on China's Illegal Fishing Activity

- ChinaDialogOcean : China wary of image crisis after Galapagos fishing scrutiny

- CTVnews : The Chinese fleet, the world's largest, accused of spearheading decline in once-abundant squid stocks

- CIMSEC : Evolution of the fleet : a closer look at the Chinese fishing vessels off the Galapagos

- The Economist : Illegal fishing fleets plunder the oceans / Illicit fishing devastates the seas and abuses crews

Wednesday, October 21, 2020

IXblue unveils The Cetos Suite, an AI Based E-Navigation solution

From NavalNews by Yannick Smaldore

To enhance navigation awareness and crews short-time decision-making, iXblue has developed an advanced e-navigation solution relying on artificial intelligence.

During Euronaval 2020, iXblue unveils for the first time its complete CETOS Suite.

Partly presented in 2018, the Cetos Suite provides enhancing resilient positioning and navigation awareness.

For coastal and littoral operations, Cetos Suite allows a safe navigation, even during intense GNSS spoofing activities.

Using AI and augmented reality, Cetos also offers a unique way to sail in a complex environment.

Recently tested by the French Navy, Cetos Suite is an advanced artificial intelligence-based navigation solution that provides naval forces with full navigational awareness, helping crews short-time decision-making and ensuring safe navigation.

Cetos e-positioning can accommodate up to 8 cameras and 2 radars alongside INS and echosounder that provide a 15-20m accuracy in GNSS-denied environment

Cetos e-positioning can accommodate up to 8 cameras and 2 radars alongside INS and echosounder that provide a 15-20m accuracy in GNSS-denied environmentBy reducing the navigational pool of error through the merging of sensors data (GNSS, INS/AHRS, radar, echosounders, cameras…), and by alerting crews members of GNSS spoofing and jamming, Cetos e-positioning brings more robust navigation to naval platforms in all environments.

Enhanced navigational awareness is also enabled thanks Cetos e-vision and its augmented reality display of all key navigation information (routes, shallow waters, buoys, AIS…) in a scene that recreates the surrounding environment.

Cetos e-positioning: sensors redundancy solution

The Cetos e-positioning is a multi-sensor positioning solution.

Connected to a wide range of sensors such as radars, cameras, echosounder, GNSS and inertial navigation systems, it improves navigation resilience within GNSS-denied environments through sensors redundancy.

- Acquires data from all available external sensors (INS/ AHRs, echosounders, cameras, radars…)

- Compares them with digital elevation models and computes resilient GNSS-free position (up to 10m accuracy)

- Displays consolidated position into WECDIS for enhanced navigation awareness

- Alerts on GNSS spoo ng/jamming by detecting discrepancies between sensor data and GNSS position

By correlating complementary navigation information, the e-positioning add-on is able to reduce the navigational pool of error and provides resilient and accurate positioning to the platform in all environments, including GNNS-denied ones.

This add-on brings safer navigation to naval operations.

Resilient positioning in all conditions :

- Robust positioning even in GNSS denied or spoofed environments

- Enhanced INS performance using multiple sensors information

- Estimated position from all sensors displayed into iXblue WECDIS

- Augmented reality representation of key navigation information

- Advanced detection of surrounding vessel through artificial intelligence

- WECDIS system pairing for user objects display in 3D scene

Augmented reality system can display AIS and radar tracks, current route of navigation and potential threats.

Augmented reality system can display AIS and radar tracks, current route of navigation and potential threats.The Cetos e-vision provides a synthetized and intuitive representation of the surrounding environment.

While connected to the bridge, it improves nautical situation awareness for a better and safer navigation.

- Immediate and comprehensive understanding of full nautical situation

- Provides optimum navigation conditions with high quality and full dimension rugged marine screens

- Panoramic video representation of routes, nearest ships, danger areas, buoys

- Custom objects representation (routes, marks, areas, AIS, radar targets,…) available within iXblue ECDIS

A new tool for safer navigation

Instead of showing the data received from ARPA, ECDIS charts and other tools in separate interfaces, the augmented reality system offers the possibility to understand the nautical situation in only a few seconds.

Through the Cetos e-vision, iXblue proposes an advanced augmented reality system displayed on dedicated screens.

Through the Cetos e-vision, iXblue proposes an advanced augmented reality system displayed on dedicated screens.Essential objects such as surrounding ships, areas of danger and the ship route are displayed in a 3D scene over a panoramic video, leading to a clear and synthetized representation of the environment.

The latest algorithms in artificial intelligence are used to bring more accurate intel to the crew and ensure a more efficient watch.

e-vision is connected to the bridge system to detect threats such as small boats or ships without AIS.

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

Jules Verne’s most famous books were part of a 54-volume masterpiece, featuring 4,000 illustrations: see them online

Not many readers of the 21st century seek out the work of popular writers of the 19th century, but when they do, they often seek out the work of Jules Verne.

Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days: fair to say that we all know the titles of these fantastical French tales from the 1860s and 70s, and more than a few of us have actually read them.

But how many of us know that they all belong to a single series, the 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires, that Verne published from 1863 until the end of his life? Verne described the project's goal to an interviewer thus: "to conclude in story form my whole survey of the world’s surface and the heavens."

Verne intended to educate, but at the same time to entertain and even artistically impress: "My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe," he said.

"And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style." This he accomplished with great success in a time and place without even what we would now consider a fully literate public.

As philosopher Marc Soriano writes of the 1860s when Verne began publishing, "The drive for literacy in France has been underway since the Guizot Law of 1833, but there is still much to do.

Any well-advised editor must aid his readers who have not yet achieved a good reading proficiency."

Hence the need for illustrations: beautiful illustrations, scientifically and narratively faithful illustrations, and above all a great many illustrations: over 4,000 of them, by the count of Arthur B.

Evans in his essay on the series' artists, "an average of 60+ illustrations per novel, one for every 6-8 pages of text." Still today, "most modern French reprints of the Voyages Extraordinaires continue to feature their original illustrations — recapturing the 'feel' of Verne’s socio-historical milieu and evoking that sense of faraway exoticism and futuristic awe which the original readers once experienced from these texts.

And yet, to date, the bulk of Vernian criticism has virtually ignored the crucial role played by these illustrations in Verne’s oeuvre."

Evans identifies four different types of illustrations in the series: "renderings of the protagonists of the story — e.g., portraits like the one of Impey Barbicane in De la terre à la lune"; "panoramic and postcard-like" views of the "exotic locales, unusual sights, and flora and fauna which the heroes encounter during their journey, like the one from Vingt mille lieues sous les mers depicting divers walking on the ocean floor"; "documentational" illustrations like "the map of the Polar regions (hand-drawn by Verne himself) for his 1864 novel Les Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras"; and portayals of "a specific moment of action in the narrative—e.g., the one from Voyage au centre de la terre where Prof.

Lidenbrock, Axel, and Hans are suddenly caught in a lightning storm on a subterranean ocean."

Verne and his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel commissioned these illustrations from no fewer than eight artists, a group including Edouard Riou, Alphonse de Neuville, Emile-Antoine Bayard (previously featured here on Open Culture), and Léon Benett — all well-known artists in late 19th-century France, and made even more so by their work in the Voyages Extraordinaires.

You can browse a complete gallery of the series' original illustrations here, and if you like, enrich the experience with this extensive essay by Terry Harpold on "reading" these images in context.

Together with the stories themselves, on the back of which Verne remains the most translated science-fiction author of all time, they allow Harpold to make the credible claim that "the textual-graphic domain constituted by these objects is unmatched in its breadth and variety; no other corpus associated with a single author is comparable."

Human knowledge of the universe has widened and deepened since Verne's day, but for sheer intellectual and adventurous wonder about what that universe might contain, has any writer, from any era or land, outdone him since?

Monday, October 19, 2020

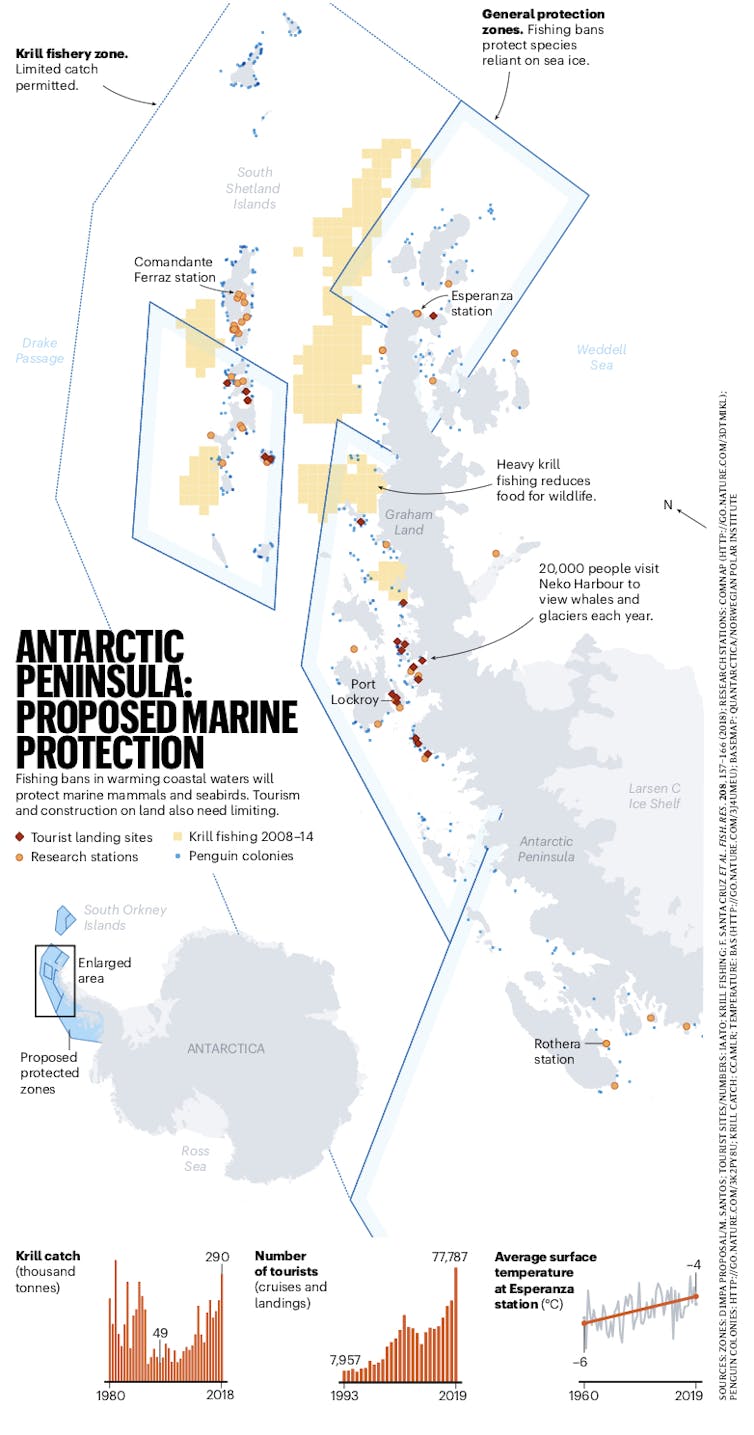

Humans threaten the Antarctic Peninsula’s fragile ecosystem. A marine protected area is long overdue

From The Conversation by Marissa Parrott, Carlyn Hogg, Cassandra Brooks, Justine Shaw & Melissa Cristina Marquez

Antarctica, the world’s last true wilderness, has been protected by an international treaty for the last 60 years.

Just 5% of the Southern Ocean is protected, leaving biodiversity hotspots exposed to threats from human activity.

The Western Antarctic Peninsula, the northernmost part of the continent and one of its most biodiverse regions, is particularly vulnerable.

In an article published in Nature today, we join more than 280 women in STEMM(science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine) from the global leadership initiative Homeward Bound to call for the immediate protection of the peninsula’s marine environment, through the designation of a marine protected area.

Our call comes ahead of a meeting, due in the next fortnight, of the international group responsible for establishing marine protected areas in the Southern Ocean.

Threats on the peninsula

The Southern Ocean plays a vital role in global food availability and security, regulates the planet’s climate and drives global ocean currents.

Climate change threatens to unravel the Southern Ocean ecosystem as species superbly adapted to the cold struggle to adapt to warmer temperatures.

The peninsula is also the most-visited part of Antarctica, thanks to its easy access, dramatic beauty, awe-inspiring wildlife and rich marine ecosystems.

Eighteen nations have science facilities on the Antarctic Peninsula, the highest concentration of research stations anywhere on the continent.

Another big threat to biodiversity in the peninsula is the commercial fishing of Antarctic krill, a small, shrimp-like crustacean which is the cornerstone of life in this region.

A cornerstone of life

Krill is a foundation of the food chain in Antarctica, with whales, fish, squid, seals and Adélie and gentoo penguins all feeding on it.

But as sea ice cover diminishes, more industrial fishing vessels can encroach on penguin, seal and whale foraging grounds, effectively acting as a competing super-predator for krill.

In the past 30 years, colonies of Adélie and Chinstrap penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula have declined by more than 50% due to reduced sea ice and krill harvesting.

Krill is a vital part of the food web in Antarctica.

Krill is a vital part of the food web in Antarctica.The krill catch here has more than tripled from 88,800 tonnes in 2000 to almost 400,000 tonnes in 2019 — the third-largest krill catch in history and a volume not seen since the 1980s.

How do we save it?

This can be done by establishing a marine protected area (MPA) in the region, which would limit or prohibit human activities such as commercial fishing.

The proposed MPA is an excellent example of balancing environmental protection with commercial interests.

Nature 586: 496-499 22 October 2020, Author provided

The second is a krill fishery zone, allowing for a precautionary management approach to commercial fishing and keeping some fishing areas open for access.

The proposed MPA would stand for 70 years, with a review every decade so zones can be adjusted to preserve ecosystems.

No more disastrous delays

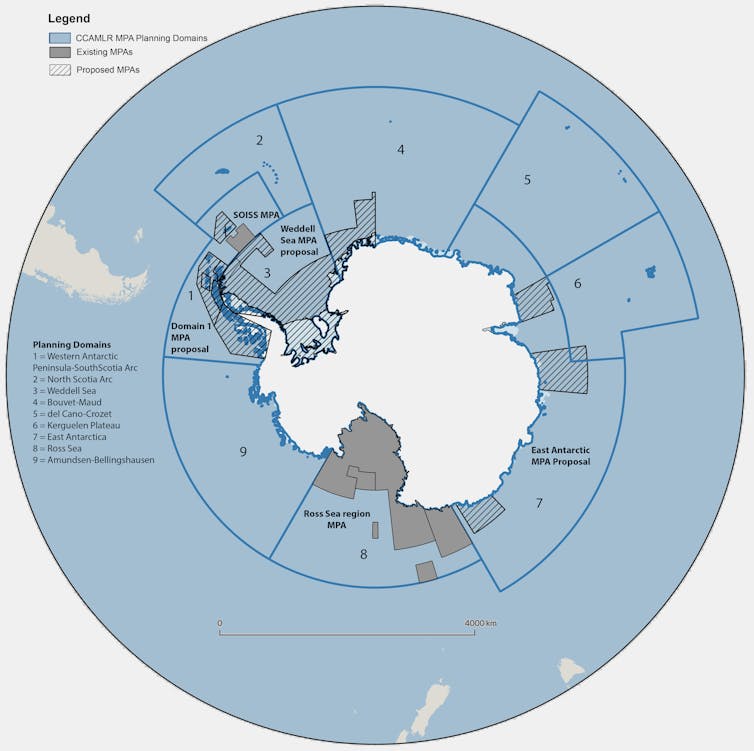

The commission is made up of 25 countries and the European Union. In its upcoming meeting, the proposed MPA will once again be considered.

A map of the current and proposed marine protected areas under consideration. Cassandra Brooks, Author provided

In fact, for eight consecutive years, the proposal for a marine park in Eastern Antarctica has failed. Delays like this are potentially disastrous for the fragile ecosystem.

Protecting the peninsula is the most pressing priority due to rising threats, but the commission should adopt all three to fulfil their 2002 commitment to establishing an MPA network in Antarctica.

If all three were established, then more than 3.2 million square kilometres of the Southern Ocean would be protected, giving biodiversity a fighting chance against the compounding threats of human activity in the region.

Links :

- The Conversation : Antarctica has lost 3 trillion tonnes of ice in 25 years. Time is running out for the frozen continent / Why marine protected areas are often not where they should be / Anatomy of a heatwave: how Antarctica recorded a 20.75°C day last month / Climate change threatens Antarctic krill and the sea life that depends on it / Australia wants to build a huge concrete runway in Antarctica. Here's why that's a bad idea