See those white dots? Those are wind turbines!

This is Windpark Fryslân, the largest freshwater wind farm on Earth!

It’s located in Lake IJssel in the Netherlands.

The array of 89 wind turbines, clustered within a hexagon shape, produces enough electricity to power about half a million homes in the Netherlands.

The array of 89 wind turbines, clustered within a hexagon shape, produces enough electricity to power about half a million homes in the Netherlands.

The 32-kilometer-long (20-mile-long) Afsluitdijk, which provides flood protection and separates the lake from the Wadden Sea, is also prominent in this #Landsat 8 satellite image.

From NASA

Suffice it to say, the Dutch have a history with wind power.

So it may come as little surprise that the Netherlands is home to a modern, second-to-none wind energy installation.

So it may come as little surprise that the Netherlands is home to a modern, second-to-none wind energy installation.

Windpark Fryslân, an array of 89 wind turbines clustered within a hexagon shape, is the largest freshwater wind farm in the world.

In this image, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 on July 8, 2023, Windpark Fryslân’s precisely spaced turbines are seen rising out of Lake IJssel.

Their arrangement in a hexagon shape is intended to minimize how much the installation obstructs the view of the horizon.

Their arrangement in a hexagon shape is intended to minimize how much the installation obstructs the view of the horizon.

The 32-kilometer-long (20-mile-long) Afsluitdijk, which provides flood protection and separates the lake from the Wadden Sea, is also prominent in the image.

The wind farm came online in autumn 2021 with the capacity to generate 1.5 terawatt hours annually.

This is equivalent to approximately 1.2 percent of electricity use in the Netherlands, or enough to power about 500,000 households.

In 2022, the installation produced 1.236 terawatt hours.

The wind farm came online in autumn 2021 with the capacity to generate 1.5 terawatt hours annually.

This is equivalent to approximately 1.2 percent of electricity use in the Netherlands, or enough to power about 500,000 households.

In 2022, the installation produced 1.236 terawatt hours.

Constructing the wind farm in Lake IJssel posed unique challenges,

according to the company Van Oord, which was part of the consortium

that built Windpark Fryslân.

A major constraint was the size of ships that could be used to transport construction materials and turbine components to the site.

The vessels had to both fit through the locks in the dike and operate in the shallow waters of the lake.

In addition, installing the rotors, which are 130 meters (430 feet) in diameter, required finding windows of relative calm in a naturally windy place.

One of the two sets of locks in the dike is located at Kornwerderzand.

A major constraint was the size of ships that could be used to transport construction materials and turbine components to the site.

The vessels had to both fit through the locks in the dike and operate in the shallow waters of the lake.

In addition, installing the rotors, which are 130 meters (430 feet) in diameter, required finding windows of relative calm in a naturally windy place.

One of the two sets of locks in the dike is located at Kornwerderzand.

Nearby, an artificial island

that was created as a construction platform now serves as a nature

reserve and bird sanctuary.

While the island is only 2 hectares (5 acres) in size, it is surrounded by 25 hectares (60 acres) of shallow water that provides habitat for fish.

Along with a new power source and wildlife habitat, the Dutch have found new recreational opportunities associated with wind project.

In October, Windpark Fryslân will be the site of the Windmill Cup, a sailing race that courses through the turbines.

While the island is only 2 hectares (5 acres) in size, it is surrounded by 25 hectares (60 acres) of shallow water that provides habitat for fish.

Along with a new power source and wildlife habitat, the Dutch have found new recreational opportunities associated with wind project.

In October, Windpark Fryslân will be the site of the Windmill Cup, a sailing race that courses through the turbines.

Links :

- NASA Earth Observatory (2021, September 6) Zuiderzee Works.

- Rijkswaterstaat, Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Afsluitdijk.

- Van Oord, YouTube (2022, January 11) Building the world’s largest offshore wind farm in inland water.

- Windpark Fryslân, Frisian Wind Energy for a Sustainable Future.

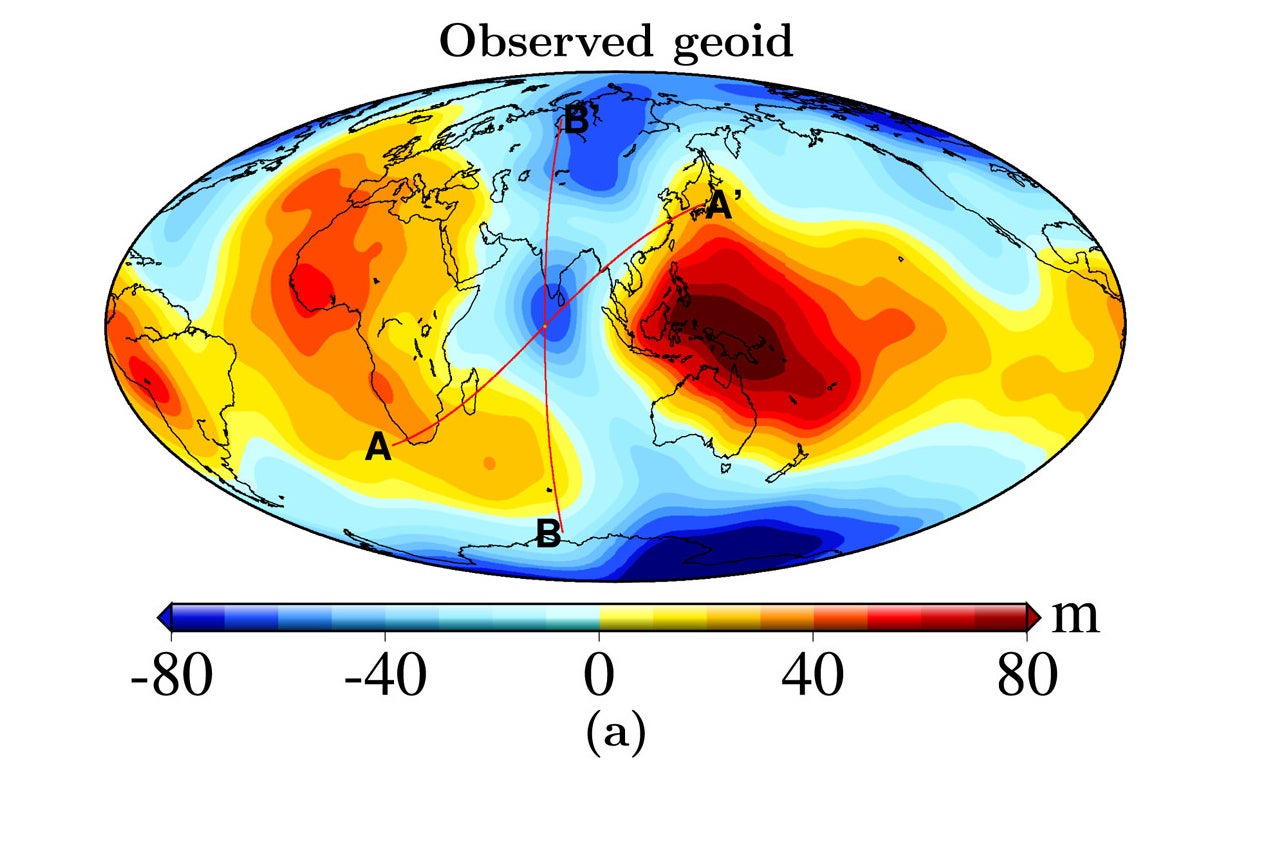

This depiction of the observed geoid of the Earth shows gravitational highs (oranges and reds) and lows (blues), measured in meters.

This depiction of the observed geoid of the Earth shows gravitational highs (oranges and reds) and lows (blues), measured in meters.

Allcard in the cabin of Temptress, August 1949

Allcard in the cabin of Temptress, August 1949