Overview of sea-floor landforms mapped in this study

From BBC by Jonathan Amos

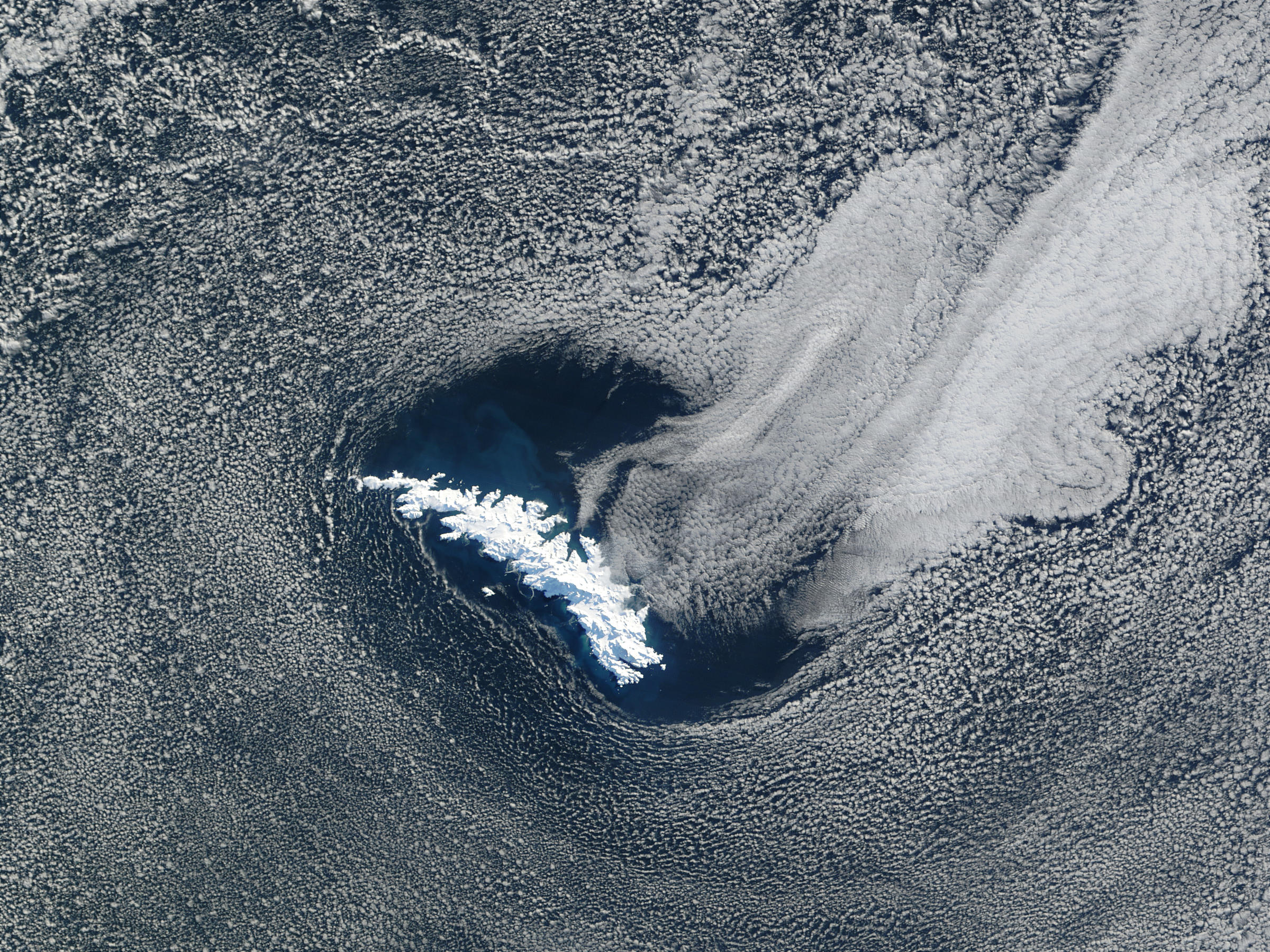

South Georgia is an island of

astonishing beauty - of imposing landscapes, and bewildering numbers of

penguins, seals and seabirds.

It also has some impressive ice fields, although none it seems quite like those of the past.

Some

20,000 years ago the island's glaciers pushed out 50km and more from

their current positions, reaching to the edge of the continental shelf.

The British Overseas Territory was in effect covered by a giant ice cap.

This realisation is reported in the current edition of the journal

Nature Communications.

South Georgia (UKHO map) in the GeoGarage platform

Located in the Southern Atlantic Ocean roughly 1,700 miles (2,735 km) due east of Argentina’s southernmost tip, South Georgia Island was a stop-over point for Sir Ernest Shackleton in November 1914.

It is the result of investigations of the seafloor by a team of scientists from the UK, Germany and Australia.

"We

were able to find a tracer of this ice cap - a ridge at the outer

margin of the continental shelf that's larger than all others, pretty

much; and it's fairly contiguous," explained Dr Alastair Graham from

Exeter University.

"You see it to the west, to the north, to the

east, and even to the south where we don't have much data. It's quite a

surprise because many scientists had assumed any ice cap was quite

small."

Dr Graham and his colleagues conducted sonar surveys

around South Georgia using the British Antarctic Survey's (BAS) research

vessel, the James Clark Ross, and Germany's RV, the Polarstern.

Map of South Georgia

(a) Southern Hemisphere map showing sites where advances of

glaciers during the Antarctic Cold Reversal have been recorded.

(b)

Regional location map illustrating modern-day mean annual position of

major Southern Ocean oceanographic fronts in relation to South Georgia.

These ships mapped the long deep troughs cut by ancient glaciers.

Evident in these channels are the countless, tell-tale markings of

bulldozed sediments known as moraines.

But to fill out their

picture, the researchers needed also to establish when these features

were produced, and so they pulled up cores of seafloor material.

Caught

up in this mud and rock are the shelly remains of tiny animals that can

be used to date the glacial deposits.

What emerges from all this

study is a story of a rapidly changing ice-scape - one that has been

incredibly sensitive to really quite small changes in temperature.

The investigation reveals that the giant ice cap was at its fullest

extent at the height of the last ice age - about 19 to 26 thousand years

ago.

Then, as the global climate warmed, the glaciers went into a

fast retreat, pulling back to positions not far beyond the present

coastline.

A pulse of cooling about 15,000 years ago saw them briefly push forward, before deglaciation took hold again.

"In

the last 10,000 years the ice cap has wobbled back and forth, but never

really gone out much beyond the fjords," Dr Graham told BBC News.

"And

then in the 1950s, things seemed to go pear-shaped for South Georgia.

The glaciers now are in a massive retreat, which could have quite

serious implications for local ecosystems."

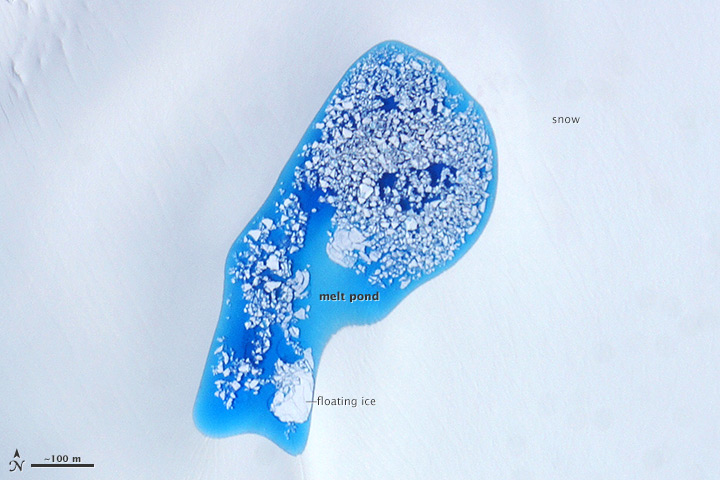

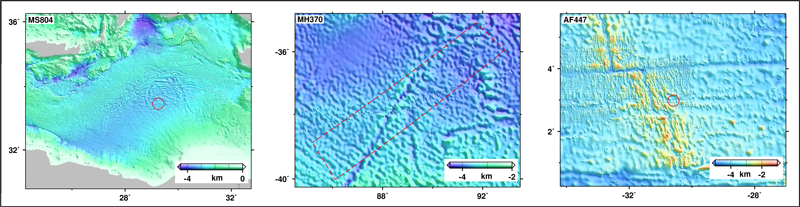

(a) Location map indicating the locations of panels b–g.

(b) Streamlined crag-and-tails and/or drumlins 0.5–1 km in length, south of Undine South Harbour;

(c) streamlined bedforms and roche moutonnée overprinted by extensive scouring in the trough feeding out of Drygalski Fjord;

(d) elongated mega-scale glacial lineations and

(e) drumlinoid bedforms that increase in elongation down-flow in the trough northwest of Church Bay;

(f)

convergence of flow patterns including a swarm of small drumlins at the

confluence of tributaries emanating from Possession Bay and Antarctic

Bay;

(g) individual drumlin imaged on flat sea-bed region south

of the central part of the island.

All multibeam data have an 8 m

grid-cell size, except for ‘f’ which is gridded at 20-m cell size. Arrows depict direction of former ice flow.

The Cumberland Trough - the seafloor scar left by a once mighty glacier

- General context map (1) for Cumberland Bay in central-north South Georgia

- Bathymetry reveals a large trough (2) spreading northeast for up to 70km

- Numerous ridges (2) of bulldozed sediment (moraines) cross the trough

- (3) Downstream of today's Nordenskjold Glacier is one large moraine

- This ridge (3) is probably the extent of a brief re-advance 15,000 years ago

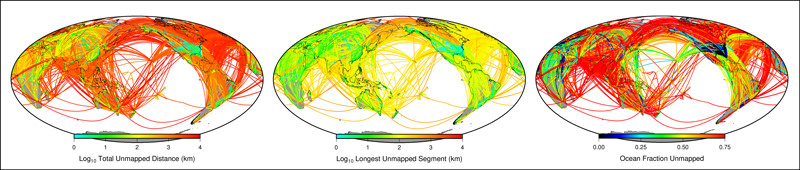

(a) Compiled swath bathymetry tracks west of the island

illustrating a large outer ridge and back-stepping recessional moraines;

profile v–x through the ridge shown in ‘c’;

(b) a sub-set of the recessional moraines in detail.

(c) profile v–x through the outer ridge showing the separation of deeper, pitted sea-floor and moraine-mantled topography inshore.

(d) streamlined subglacial bedforms south of the island, resembling drumlins formed by warm-based, fast glacial flow.

(e) topographic profile y–z across the bedforms illustrating their range of amplitudes and typical wavelengths. Profile located in ‘d’. Data in ‘a’ gridded at 5 m grid cell size, and at 8 m grid-cell size in ‘d’.

With so many of the glaciers today pulling back on to land, they no

long provide as much crushed rock to the surrounding ocean as they once

did.

This potentially could put new constraints on the bio-productivity of the region, said co-worker Prof Dominic Hodgson from BAS.

"As

they erode, South Georgia and the other sub-antarctic islands put 'rock

flour' in the ocean and that provides a supply of iron. Iron is the

limiting nutrient," he explained.

"It gives rise to big blooms of

plankton which then drive the ecosystem from the bottom up - from the

plankton and zooplankton, to the krill, all the way up to the seals,

birds and penguins. This is why you get this intense concentration of

biota around South Georgia."

South Georgia Island

Today, the glaciers are in an accelerated reversal, with many pulling back up on to the land

It is an interesting question, however, as to what all this wildlife

did when South Georgia was covered by a huge ice cap.

Many of its bird

species, such as the albatrosses for example, nest in burrows and so

need some clear, ice-free land to breed.

There are also some

endemic animals - they exist nowhere else.

For these creatures to have

survived through the great glaciation there must have been gaps in the

ice cap.

The team is trying to establish where these refugia might have

been.

Another spillover from the study is determining what the

South Georgia experience tells us about higher latitudes, such as the

Antarctic Peninsula.

Away from the brutal westerlies, South Georgia has some green spaces

The glaciated "finger" of land that juts up from the White Continent

towards South America is already one of the fastest warming locations on

Earth.

Scientists who try to model its future behaviour now have a new anchor point in their simulations thanks to this study.

"South

Georgia shows us what the response is of an ice sheet to really very

moderate changes in temperature, both in the ocean and the atmosphere,"

said Prof Hodgson.

"We can now take those responses and push them

further south and get a very good idea of what might happen to the

Antarctic Peninsula, and indeed any ice sheet that is close to its

thermal limit."

Links :