From The Guardian by Hettie Judah

They may have infuriated the censor, but these beautiful films and photographs of cavorting creatures caused a sensation in the 30s.

As Ikon’s new exhibition shows, they have been overlooked for too long

Desperately seeking the nose of a shrimp …

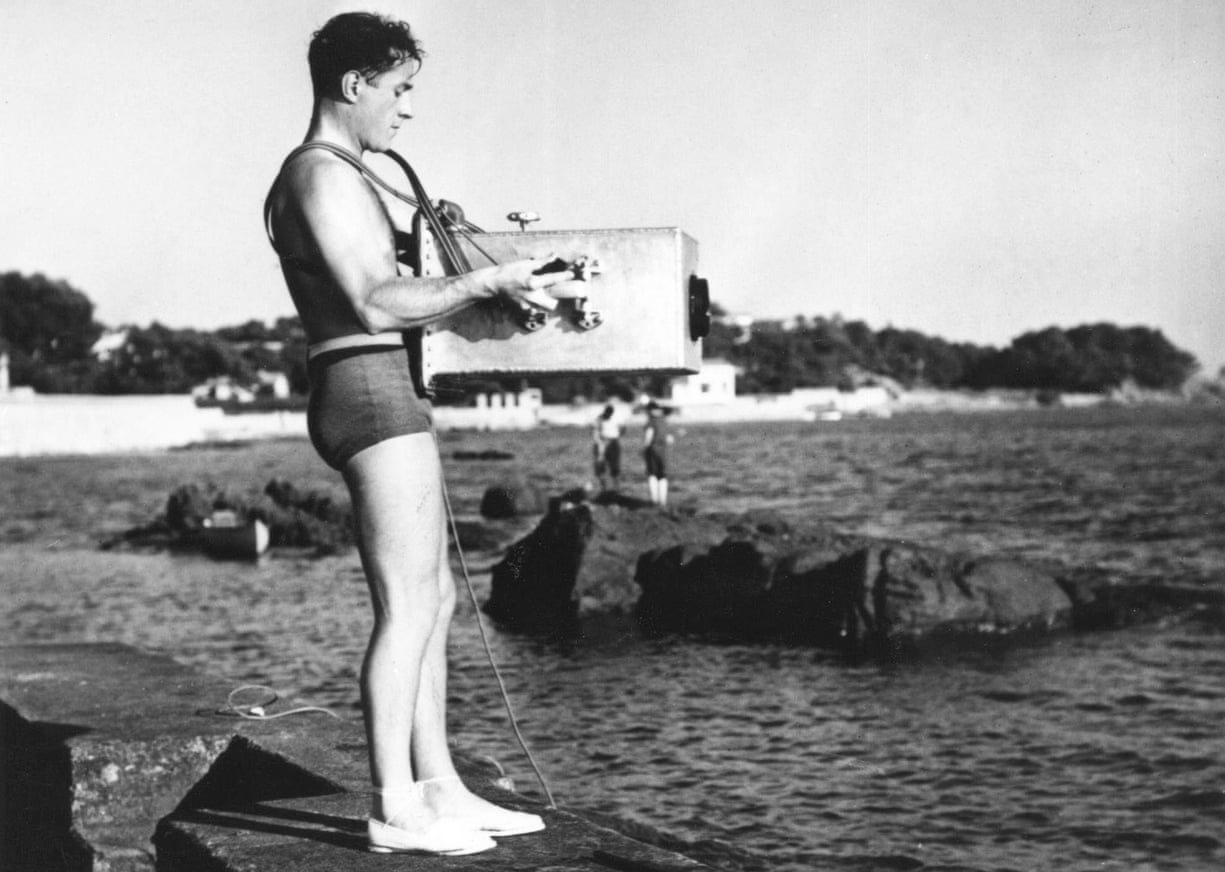

Jean Painlevé with his camera in a waterproof box, 1935

Photograph: Image courtesy of Archives Jean Painlevé, Paris

In the course of his lifetime, the aquatic French film-maker Jean Painlevé hung out with Man Ray and Alexander Calder, showed his work in galleries alongside the surrealists, and inspired George Balanchine to choreograph a lobster ballet.

His most successful film, 1934’s L’Hippocampe ou Cheval Marin, didn’t just incur the wrath of censors with its intimate footage of copulating seahorses.

It also provoked such a mania for the arresting little creatures that the Frenchman, somewhat improbably, launched a range of fashion accessories.

Overlooked for decades, Painlevé’s curious – and curiously beautiful – underwater movies have been championed by France’s current crop of global art stars, among them Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno.

In recent years, his aquatic films have been seen in group exhibitions, becoming a point of reference for the art world’s mounting obsession with the animal kingdom.

Now Ikon in Birmingham is presenting his first British solo show.

A still from The Seahorse, 1931.

Photograph: Courtesy of Archives Jean Painleve, Paris

The wallpaper, which enlivens the opening gallery, is a coral and seahorse design created by Painlevé’s partner Geneviève Hamon for a silk scarf.

The exhibition captures the range of Painlevé’s output in a career that stretched from the 1920s to the 70s.

On the walls hang intimate shots – the nose of a shrimp, the horn of a seahorse, the suckers of an octopus – all made with a microscope.

Taken in the 1920s and 30s, when Painlevé exhibited them blown up to monstrous dimensions, they are crisp, luminous and mysterious.

Of the four films shown, two are studies of aquatic creatures: the famous seahorses and the tiny Acera sea snails.

Both are oddly erotic in places. Painlevé allowed himself to be transported by his own delight in unexpected phenomena.

In the case of the Acera, these include hermaphroditic mating practices and a lavish, highly balletic dance, in which the snails use their tiny shells as ballast while they shoot themselves up and down in the water.

Painlevé sets this against music by Pierre Jansen – a composer best known for his work with Claude Chabrol – with each swoop echoed in the music, as though they were performing to a score for waltzing lovers.

Surreal sea … Crab Claw, 1928.

Photograph: Courtesy of Archives Jean Painlevé, Paris

While this may sound like something straight out of The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, Painlevé’s methods were rather more homespun than those of Wes Anderson’s titular hero.

In place of leopard sharks tracked in a minisub, the stars of Painlevé’s movies were tiny creatures – shrimp, squid, octopus, slug – caught by hand in shallow waters off the coast of Brittany.

Most of Painlevé’s films were made in aquariums in his studio laboratory, some double-walled to protect the inhabitants from the heat of the lights.

Beside the film-maker’s enthusiasm for his tiny subjects, what stands out is the use of cutting-edge and scientific equipment – underwater cameras and microscopy – that offered a new glimpse of this little-known world.

Of the other two films, one – a distinctly psychedelic study of the proliferation of liquid crystals – underscores Painlevé’s status as a scientist.

The other, which shows Alexander Calder operating a mechanical circus created in the 1920s, is a reminder of the film-maker’s close ties to the art world. Membership of the French Union of Communist Students in his younger days had also put Painlevé in touch with avant-garde film-makers including Luis Buñuel and Sergei Eisenstein, and he went on to speak and write extensively about his creative philosophies.

In 1948, he suggested Ten commandments of film-making, warning against the over-reliance on special effects and the use of monotonous sequences.

For all his associations with the avant-garde, Painlevé’s great ambition was that his films would reach the widest possible audience, spreading his enthusiasm and scientific knowledge.

They are, to this end, unapologetically entertaining, often highly anthropomorphic.

Watching the male seahorse eject hundreds of tiny babies from its pouch, Painlevé notes what seems to be alarm in the darting of its eyes, likening the whole experience to the contractions of human labour.

Part of L’hippocampe’s sensational success can be attributed to how its subjects upturned gender roles, something Painlevé clearly approved off, since one of his Commandments decrees: “You will refuse to direct a film if your convictions are not expressed.”

Narrating to some footage of female seahorses impregnating the male with eggs, Painlevé was emphatic in his approval, and no less enthusiastic about the subsequent division of labour in pregnancy and parenthood.

There’s some aquatic-themed costume jewellery on show in a glass vitrine here.

To the casual eye, it may seem a little out of place, but don’t be fooled.

That sea horse motif was a potent symbol of equality.

Links :

- The Guardian : The underwater world of Jean Painlevé in pictures

No comments:

Post a Comment