Some 330 people, most of them Indigenous, live in the village of St. Paul, about 800 miles west of Anchorage, where the local economy depends almost entirely on the commercial snow crab business.

Over the past few years, 10 billion snow crabs have unexpectedly vanished from the Bering Sea.

I was traveling there to find out what the villagers might do next.

The arc of St. Paul’s recent story has become a familiar one—so familiar, in fact, that I couldn’t blame you if you missed it.

Alaska news is full of climate elegies now—every one linked to wrenching changes caused by burning fossil fuels.

I grew up in Alaska, as my parents did before me, and I’ve been writing about the state’s culture for more than 20 years.

Some Alaskans’ connections go far deeper than mine.

Alaska Native people have inhabited this place for more than 10,000 years.

As I’ve reported in Indigenous communities, people remind me that my sense of history is short and that the natural world moves in cycles.

People in Alaska have always had to adapt.

Even so, in the past few years I’ve seen disruptions to economies and food systems, as well as fires, floods, landslides, storms, coastal erosion, and changes to river ice—all escalating at a pace that’s hard to process.

Increasingly, my stories veer from science and economics into the fundamental ability of Alaskans to keep living in rural places.

You can’t separate how people understand themselves in Alaska from the landscape and animals.

The idea of abandoning long-occupied places echoes deep into identity and history.

I’m convinced the questions Alaskans are grappling with—whether to stay in a place and what to hold onto if they can’t—will eventually face everyone.

I’ve given thought to solastalgia—the longing and grief experienced by people whose feeling of home is disrupted by negative changes in the environment.

But the concept doesn’t quite capture what it feels like to live here now.

A few years ago, I was a public radio editor on a story out of the small Southeast Alaska town of Haines about a storm that came through carrying a record amount of rain.

The morning started routinely—a reporter on the ground calling around, surveying the damage.

But then, a hillside rumbled down, taking out a house and killing the people inside.

I still think of it—people going through regular routines in a place that feels like home, but that, at any time, might come cratering down.

There’s a prickly anxiety humming beneath Alaska life now, like a wildfire that travels for miles in the loamy surface of soft ground before erupting without notice into flames.

But in St. Paul, there was no wildfire—only fat raindrops on my windshield as I loaded into a truck at the airport.

In my notebook, tucked into my backpack, I’d written a single question: “What does this place preserve?”

THE SANDY ROAD from the airport in late March led across wide, empty grassland, bleached sepia by the winter season.

Town appeared beyond a rise, framed by towers of rusty crab pots.

It stretched across a saddle of land, with rows of brightly painted houses—magentas, yellows, teals—stacked on either hillside.

The grocery store, school, and clinic sat in between them, with a 100-year-old Russian Orthodox church named for Saints Peter and Paul, patrons of the day in June 1786 when Russian explorer Gavril Pribylov landed on the island.

A darkened processing plant, the largest in the world for snow crabs, rose above the quiet harbor.

You’re probably familiar with sweet, briny snow crab—Chionoecetes opilio—which is commonly found on the menus of chain restaurants like Red Lobster.

A plate of crimson legs with drawn butter there will cost you $32.99.

In a regular year, a good portion of the snow crab America eats comes from the plant, owned by the multibillion-dollar company Trident Seafoods.

Not that long ago, at the peak of crab season in late winter, temporary workers at the plant would double the population of the town, butchering, cooking, freezing, and boxing 100,000 pounds of snow crab per day, along with processing halibut from a small fleet of local fishers.

Boats full of crab rode into the harbor at all hours, sometimes motoring through swells so perilous they’ve become the subject of a popular collection of

YouTube videos.

People filled the town’s lone tavern in the evenings, and the plant cafeteria, the only restaurant in town, opened to locals.

In a normal year, taxes on crab and local investments in crab fishing could bring St. Paul more than $2 million.

Then came the massive, unexpected drop in the crab population—a crash scientists linked to record-warm ocean temperatures and less ice formation, both associated with climate change.

In 2021, federal authorities severely limited the allowable catch.

In 2022, they closed the fishery for the first time in 50 years.

Industry losses in the Bering Sea crab fishery climbed into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

St. Paul lost almost 60 percent of its tax revenue overnight.

Leaders declared a “cultural, social, and economic emergency.” Town officials had reserves to keep the community’s most basic functions running, but they had to start an online fundraiser to pay for emergency medical services.

Through the windshield of the truck I was riding in, I could see the only cemetery on the hillside, with weathered rows of Orthodox crosses.

Van Halen played on the only radio station.

I kept thinking about the meaning of a cultural emergency.

Some of Alaska’s Indigenous villages have been occupied for thousands of years, but modern rural life can be hard to sustain because of the high costs of groceries and fuel shipped from outside, limited housing, and scarce jobs.

St. Paul’s population was already shrinking ahead of the crab crash.

Young people departed for educational and job opportunities.

Older people left to be closer to medical care.

St. George, its sister island, lost its school years ago and now has about 40 residents.

If you layer climate-related disruptions—such as changing weather patterns, rising sea levels, and shrinking populations of fish and game—on top of economic troubles, it just increases the pressure to migrate.

When people leave, precious intangibles vanish as well: a language spoken for 10,000 years, the taste for seal oil, the method for weaving yellow grass into a tiny basket, words to hymns sung in Unangam Tunuu, and maybe most importantly, the collective memory of all that had happened before.

St.

Paul played a pivotal role in Alaska’s history.

It’s also the site of several dark chapters in America’s treatment of Indigenous populations.

But as people and their memories disappear, what remains?

There is so much to remember.

THE PRIBILOFS CONSIST of five volcano-made islands—but people now live mainly on St.

Paul.

The island is rolling, treeless, with black sand beaches and towering basaltic cliffs that drop into a crashing sea.

In the summer it grows verdant with mosses, ferns, grasses, dense shrubs, and delicate wildflowers.

Millions of migratory seabirds arrive every year, making it a tourist attraction for birders that’s been called the “Galapagos of the North.”

Driving the road west along the coast, you might glimpse a few members of the island’s half-century-old domestic reindeer herd.

The road gains elevation until you reach a trailhead.

From there you can walk the soft fox path for miles along the top of the cliffs, seabirds gliding above you—many species of gulls, puffins, common murres with their white bellies and obsidian wings.

In spring, before the island greens up, you can find the old ropes people use to climb down to harvest murre eggs.

Foxes trail you.

Sometimes you can hear them barking over the sound of the surf.

Two-thirds of the world’s population of northern fur seals—hundreds of thousands of animals—return to beaches in the Pribilofs every summer to breed.

Valued for their dense, soft fur, they were once hunted to near extinction.

Alaska’s history since contact is a thousand stories of outsiders overwriting Indigenous culture and taking things—land, trees, oil, animals, minerals—of which there is a limited supply.

St. Paul is perhaps among the oldest examples.

The Unangax̂—sometimes called Aleuts—had lived on a chain of Aleutian Islands to the south for thousands of years and were among the first Indigenous people to see outsiders—Russian explorers who arrived in the mid-1700s.

Within 50 years, the population was nearly wiped out.

People of Unangax̂ descent are now scattered across Alaska and the world.

Just 1,700 live in the Aleutian region.

St. Paul is home to one of the largest Unangax̂ communities left.

Many residents are related to Indigenous people kidnapped from the Aleutian Islands and forced by Russians to hunt seals as part of a lucrative 19th-century fur trade.

St. Paul’s robust fur operation, subsidized by slave labor, became a strong incentive for the United States’ purchase of the Alaska territory from Russia in 1867.

On the plane ride in, I read the 2022 book that detailed the history of piracy in the early seal trade on the island, Roar of the Sea: Treachery, Obsession, and Alaska’s Most Valuable Wildlife by Deb Vanasse.

One of the facts that stayed with me: Profits from Indigenous sealing allowed the US to recoup the $7.2 million it paid for Alaska by 1905.

Another: After the purchase, the US government controlled islanders well into the mid-20th century as part of an operation many describe as indentured servitude.

The government was obligated to provide for housing, sanitation, food, and heat on the island, but none were adequate.

Considered “wards of the state,” the Unangax̂ were compensated for their labors in meager rations of canned food.

Once a week, Indigenous islanders were allowed to hunt or fish for subsistence.

Houses were inspected for cleanliness and to check for home brew.

Travel on and off the island was strictly controlled.

Mail was censored.

Between 1870 and 1946, Alaska Native people on the islands earned an estimated $2.1 million, while the government and private companies raked in $46 million in profits.

Some inequitable practices continued well into the 1960s, when politicians, activists, and the

Tundra Times, an Alaska Native newspaper, brought the story of the government’s treatment of Indigenous islanders to a wider world.

During World War II, the Japanese bombed Dutch Harbor and the US military gathered St.

Paul residents with little notice and transported them 1,200 miles to a detention camp at a decrepit cannery in Southeast Alaska at Funter Bay.

Soldiers ransacked their homes on St.

Paul and slaughtered the reindeer herd so there would be nothing for the Japanese if they occupied the island.

The government said the relocation and detention were for protection, but they brought the Unangax̂ back to the island during the seal season to hunt.

A number of villagers died in cramped and filthy conditions with little food.

But Unangax̂ also became acquainted with Tlingits from the Southeast region, who had been organizing politically for years through the

Alaska Native Brotherhood/Sisterhood organization.

After the war, the Unangax̂ people returned to the island and began to organize and agitate for better conditions.

In one famous suit, known as “the corned beef case,” Indigenous residents working in the seal industry filed a complaint with the government in 1951.

According to the complaint, their compensation, paid in the form of rations, included corned beef, while white workers on the island received fresh meat.

After decades of hurdles, the case was settled in favor of the Alaska Native community for more than $8 million.

“The government was obligated to provide ‘comfort,’ but ‘wretchedness’ and ‘anguish’ are the words that more accurately describe the condition of the Pribilof Aleuts,” read the settlement, awarded by the Indian Claims Commission in 1979.

The commission was established by Congress in the 1940s to weigh unresolved tribal claims.

Prosperity and independence finally came to St. Paul after commercial sealing was halted in 1984.

The government brought in fishermen to teach locals how to fish commercially for halibut and funded the construction of a harbor for crab processing.

By the early ’90s, crab catches were enormous, reaching between 200 and 300 million pounds per year.

(By comparison, the allowable catch in 2021, the first year of marked crab decline, was 5.5 million pounds, though fishermen couldn’t catch even that.) The island’s population reached a peak of more than 700 people in the early 1990s but has been on a slow decline ever since.

I’D COME TO the island in part to talk to Aquilina Lestenkof, a historian deeply involved in language preservation.

I found her on a rainy afternoon in the bright blue wood-walled civic center, which is a warren of classrooms and offices, crowded with books, artifacts, and historic photographs.

She greeted me with a word that starts at the back of the throat and rhymes with “song.”

“Aang,” she said.

Lestenkof moved from St. George, where she was born, to St. Paul when she was four.

Her father, who was also born in St. George, became the village priest.

She had long salt-and-pepper hair and a tattoo that stretched across both her cheeks made of curved lines and dots.

Each dot represents an island where a generation of her family lived, beginning with Attu in the Aleutians, then traveling to the Russian Commander Islands—also a site of a slave sealing operation—as well as Atka, Unalaska, St. George, and St. Paul.

“I’m the fifth generation having my story travel through those six islands,” she said.

Lestenkof is a grandmother, related to a good many people in the village and married to the city manager.

For the past 10 years she’s been working on revitalizing Unangam Tunuu, the Indigenous language.

Only one elder in the village speaks fluently now.

He’s among the fewer than 100 fluent speakers left on the planet, though many people in the village understand and speak some words.

Back in the 1920s, teachers in the government school put hot sauce on her father’s tongue for speaking Unangam Tunuu, she told me.

He didn’t require his children to learn it.

There’s a way that language shapes how you understand the land and community around you, she said, and she wanted to preserve the parts of that she could.

“[My father] said, ‘If you thought in our language, if you thought from our perspective, you’d know what I’m talking about,’” she said.

“I felt cheated.”

She showed me a wall covered with rectangles of paper that tracked grammar in Unangam Tunuu.

Lestenkof said she needed to hunt down a fluent speaker to check the grammar.

Say you wanted to say “drinking coffee,” she explained.

You might learn that you don’t need to add the word for “drinking.” Instead, you might be able to change the noun to a verb just by adding an ending to it.

Her program had been supported by money from a local nonprofit invested in crabbing and, more recently, by grants, but she was recently informed that she may lose funding.

Her students come from the village school, which is shrinking along with the population.

I asked her what would happen if the crabs fail to come back.

People could survive, she said, but the village would look very different.

“Sometimes I’ve pondered, is it even right to have 500 people on this island?” she said.

If people moved off, I asked her, who would keep track of its history?

“Oh, so we don’t repeat it?” she asked, laughing.

“We repeat history.

We repeat stupid history, too.”

Until recently, during the crab season, the Bering Sea fleet had some 70 boats, most of them ported out of Washington state, with crews that came from all over the US.

Few villagers work in the industry, in part because the job only lasts for a short season.

Instead, they fish commercially for halibut, have positions in the local government or the tribe, or work in tourism.

Processing is hard, physical labor—a schedule might be seven days a week, 12 hours a day, with an average pay of $17 an hour.

As with lots of processors in Alaska, nonresident workers on temporary visas from the Philippines, Mexico, and Eastern Europe fill many of the jobs.

The crab plant echoes the dynamics of commercial sealing, she said.

Its workers leave their homeland, working hard labor for low pay.

It was one more industry depleting Alaska’s resources and sending them across the globe.

Maybe the system didn’t serve Alaskans in a lasting way.

Do people eating crab know how far it travels to the plate?

“We have the seas feeding people in freakin’ Iowa,” she said.

“They shouldn’t be eating it.

Get your own food.”

OCEAN TEMPERATURES ARE increasing all over the world, but sea surface temperature change is most dramatic in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

As the North Pacific experiences sustained increases in temperature, it also warms up the Bering Sea to the north, through marine heat waves.

During the past decade, these heat waves have grown more frequent and longer-lasting than at any time since record-keeping began more than 100 years ago.

Scientists expect this trend to continue.

A marine heat wave in the Bering Sea between 2016 and 2019 brought record warmth, preventing ice formation for several winters and affecting numerous cold-water species, including Pacific cod and pollock, seals, seabirds, and several types of crab.

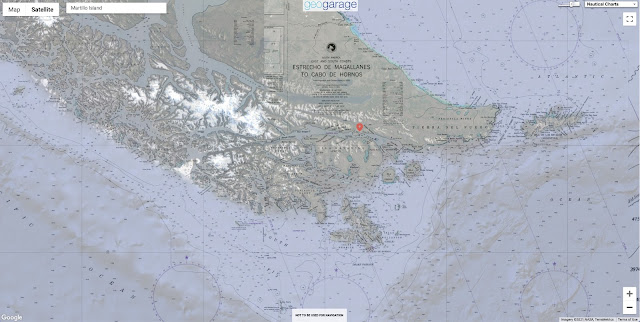

Crab fishermens' pots sit idle outside of the community of St. Paul since the crab crash and subsequent closure.

(Photo by Nathaniel Wilder)

Snow crab stocks always vary, but in 2018 a survey indicated that the snow crab population had exploded—it showed a 60 percent boost in market-sized male crab.

(Only males of a certain size are harvested.) The next year showed abundance had fallen by 50 percent.

The survey skipped a year due to the pandemic.

Then, in 2021, the survey showed that the male snow crab population had dropped by more than 90 percent from its high point in 2018.

All major Bering Sea crab stocks, including red king crab and bairdi crab, were way down too.

The most recent survey showed a decline in snow crabs from 11.7 billion in 2018 to 1.9 billion in 2022.

Scientists think a large pulse of young snow crabs came just before years of abnormally warm water temperatures, which led to less sea ice formation.

One hypothesis is that these warmer temperatures drew sea animals from warmer climates north, displacing cold water animals, including commercial species like crab, pollock, and cod.

Another has to do with food availability.

Crabs depend on cold water—water that’s 2 degrees Celsius (35.6 degrees Fahrenheit), to be exact—that comes from storms and ice melt, forming cold pools on the bottom of the ocean.

Scientists theorize that cold water slows crabs’ metabolisms, reducing their need for food.

But with the warmer water on the bottom, they needed more food than was available.

It’s possible they starved or cannibalized each other, leading to the crash now underway.

Either way, warmer temperatures were key.

And there’s every indication temperatures will continue to increase with global warming.

“If we’ve lost the ice, we’ve lost the 2-degree water,” Michael Litzow, shellfish assessment program manager with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told me.

“Cold water, it’s their niche—they’re an Arctic animal.”

The snow crab may rebound in a few years, so long as there aren’t any periods of warm water.

But if warming trends continue, as scientists predict, the marine heat waves will return, pressuring the crab population again.

BONES LITTER THE wild part of St. Paul Island like Ezekiel’s Valley in the Old Testament—reindeer ribs, seal teeth, fox femurs, whale vertebrae, and air-light bird skulls hide in the grass and along the rocky beaches, evidence of the bounty of wildlife and 200 years of killing seals.

When I went to visit Phil Zavadil, the city manager and Aqualina’s husband, in his office, I found a couple of sea lion shoulder bones on a coffee table.

Called “yes/no” bones, they have a fin along the top and a heavy ball at one end.

In St. Paul, they function like a magic eight ball.

If you drop one and it falls with the fin pointing right, the answer to your question is yes.

If it falls pointing left, the answer is no.

One large one said “City of St. Paul Big-Decision Maker.” The other one was labeled “budget bone.”

The long-term health of the town, Zavadil told me, wasn’t in a totally dire position yet when it came to the sudden loss of the crab.

It had invested during the heyday of crabbing and with a somewhat reduced budget could likely sustain itself for a decade.

“That’s if something drastic doesn’t happen.

If we don’t have to make drastic cuts,” he said.

“Hopefully the crab will come back at some level.”

The easiest economic solution for the collapse of the crab fishery would be to convert the plant to process other fish, Zavadil said.

There were some regulatory hurdles, but they weren’t insurmountable.

City leaders were also exploring mariculture—raising seaweed, sea cucumbers, and sea urchins.

That would require finding a market and testing mariculture methods in St. Paul’s waters.

The fastest timeline for that was maybe three years, he said.

Or they could promote tourism.

The island has about 300 tourists a year, most of them hardcore birders.

“But you think about just doubling that,” he said.

The trick was to stabilize the economy before too many working-age adults moved away.

There were already more jobs than people to fill them.

Older people were passing away, younger families were moving out.

“I had someone come up to me the other day and say, ‘The village is dying,’” he said, but he didn’t see it that way.

There were still people working and lots of solutions to try.

“There is cause for alarm if we do nothing,” he said.

“We’re trying to work on things and take action the best we can.”

AQUILINA LESTENKOF’S NEPHEW, Aaron Lestenkof, is an island sentinel with the tribal government, a job that entails monitoring wildlife and overseeing the removal of an endless stream of trash that washes up ashore.

He drove me along a bumpy road down the coast to see the beaches that would soon be noisy and crowded with seals.

We parked, and I followed him to a wide field of nubby vegetation stinking of seal scat.

A handful of seal heads popped up over the rocks.

They eyed us, then shimmied into the surf.

In the old days, Alaska Native seal workers used to walk out onto the crowded beaches, club the animals in the head, and then stab them in the heart.

They took the pelts and harvested some meat for food, but some went to waste.

Aquilina Lestenkof told me taking animals like that ran counter to how Unangax̂ related to the natural world before the Russians came.

“You have a prayer or ceremony attached to taking the life of an animal—you connect to it by putting the head back in the water,” she said.

Slaughtering seals for pelts made people numb, she told me.

The numbness passed from one generation to the next.

The era of crabbing had been in some ways a reparation for all the years of exploitation, she said.

Climate change brought new, more complex problems.

I asked Aaron Lestenkof if his elders ever talked about the time in the detention camp where they were sent during World War II.

He told me his grandfather, Aquilina’s father, sometimes recalled a painful experience of having to drown rats in a bucket there.

The act of killing animals that way was compulsory—the camp had become overrun with rats—but it felt like an ominous affront to the natural order, a trespass he’d pay for later.

Every human action in nature has consequences, he often said.

Later, when he lost his son, he remembered drowning the rats.

“Over at the harbor, he was playing and the waves were sweeping over the dock there.

He got swept out and he was never found,” Aaron Lestenkof said.

“That’s, like, the only story I remember him telling.”

We picked our way down a rocky beach littered with trash—faded coral buoys, disembodied plastic fishing gloves and boots, an old ship’s dishwasher lolling open.

He said the animals around the island were changing in small ways.

There were fewer birds now.

A handful of seals were now living on the island year-round, instead of migrating south.

Their population was also declining.

People still fish, hunt marine mammals, collect eggs, and pick berries.

Aaron Lestenkof hunts red-legged kittiwakes and king eiders, though he doesn’t have a taste for the bird meat.

He finds elders who do like them, but that’s gotten harder.

He wasn’t looking forward to the lean years of waiting for the crabs to return.

Proceeds from the community’s investment in crabbing boats had paid the heating bills of older people; the boats also supplied the elderly with crab and halibut for their freezers.

They supported education programs and environmental cleanup efforts.

But now, he said, having the crab gone would “affect our income and the community.”

Aaron Lestenkof was optimistic that they might cultivate other industries and grow tourism.

He hoped so, because he never wanted to leave the island.

His daughter was away at boarding school because there was no in-person high school any more.

He hoped, when she grew up, that she’d want to return and make her life in town.

On Sunday morning, the 148-year-old church bell at Saints Peter and Paul Russian Orthodox Church tolled through the fog.

A handful of older women and men filtered in and stood on separate sides of the church among gilded portraits of the saints.

The church has been part of village life since the beginning of Russian occupation, one of the few places, people said, where Unangam Tunuu was welcome.

A priest sometimes travels to the island, but that day George Pletnikoff Jr, a local, acted as subdeacon, singing the 90-minute service in English, Church Slavonic, and Unangam Tunuu.

George helps with Aquilina Lestenkof’s language class.

He is newly married with a 6-month-old baby.

After the service, he told me that maybe people weren’t supposed to live on the island.

Maybe they needed to leave that piece of history behind.

“This is a traumatized place,” he said.

It was only a matter of time until the fishing economy didn’t serve the village anymore and the cost of living would make it hard for people to stay, he said.

He thought he’d move his family south to the Aleutians, where his ancestors came from.

“Nikolski, Unalaska,” he told me.

“The motherland.”

The next day, just before I headed to the airport, I stopped back at Aquilina Lestenkof’s classroom.

A handful of middle school students arrived, wearing oversize sweatshirts and high-top Nikes.

She invited me into a circle where students introduced themselves in Unangam Tunuu, using hand gestures that helped them remember the words.

After a while, I followed the class to a work table.

Lestenkof guided them, pulling a needle through a papery dried seal esophagus to sew a waterproof pouch.

The idea was that they’d practice words and skills that generations before them had carried from island to island, hearing and feeling them until they became so automatic they could teach them to their own children.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/X4JT3WPTHRF5BAMQMXYRKCWENU.jpg)