A worrying new GPS Spoofing method has been detected being used in Shanghai, China and it has everyone worried.

Nobody knows who is behind the attacks but the suspicion is the technology is so sophisticated that it must be state sponsored.

The first signs of an issue began when ship crews, manoeuvring their vessels in the congested waterways of Shanghai port observed other ship traffic, supposedly ahead of them in the shipping lane, disappearing from their navigation displays only to reappear a minute or so later apparently tied up at the dockside.

Now new research has revealed that thousands of vessels have been victim of this new type of spoofing and the most worrying aspect is experts have no idea how it is being done.

It's one thing to jam a GPS signal, but spoofing a signal in this way is much more difficult.

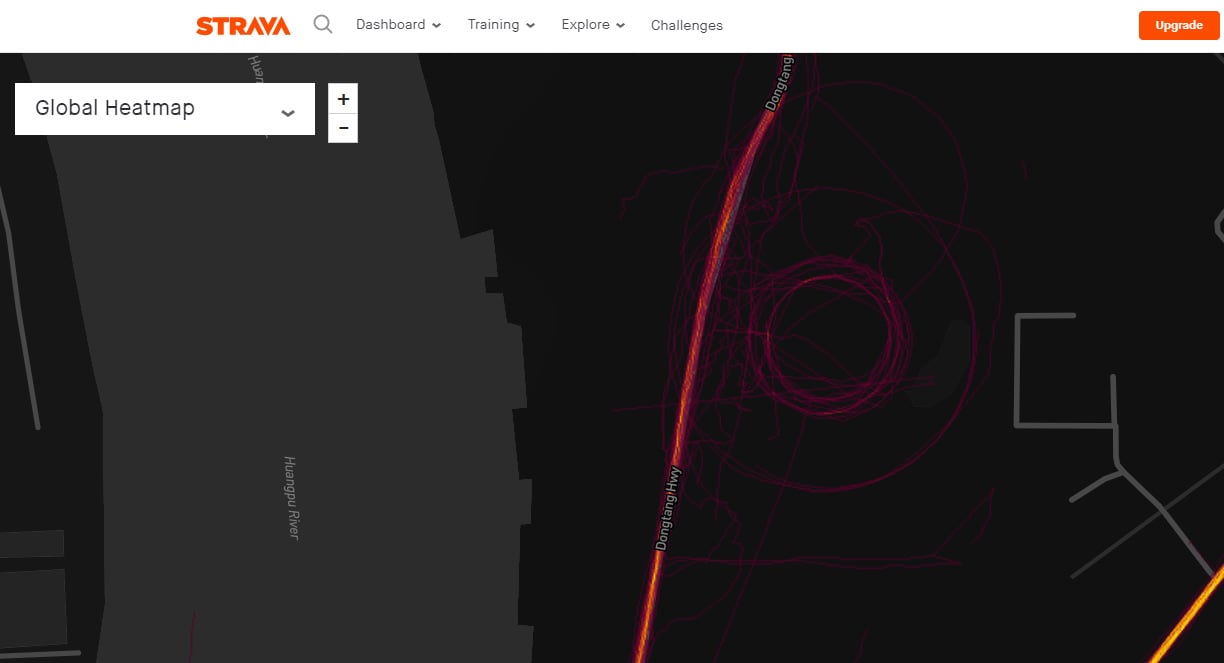

image : A "crop circle" of spoofed GPS locations in Shanghai that C4ADS discovered when it plotted the compromised AIS data.

source : C4ADS

Nobody knows who is behind the attacks but the suspicion is the technology is so sophisticated that it must be state sponsored.

The first signs of an issue began when ship crews, manoeuvring their vessels in the congested waterways of Shanghai port observed other ship traffic, supposedly ahead of them in the shipping lane, disappearing from their navigation displays only to reappear a minute or so later apparently tied up at the dockside.

Now new research has revealed that thousands of vessels have been victim of this new type of spoofing and the most worrying aspect is experts have no idea how it is being done.

It's one thing to jam a GPS signal, but spoofing a signal in this way is much more difficult.

image : A "crop circle" of spoofed GPS locations in Shanghai that C4ADS discovered when it plotted the compromised AIS data.

source : C4ADS

From MIT TechnologyReview by Mark Harris

A sophisticated new electronic warfare system is being used at the world’s busiest port.

But is it sand thieves or the Chinese state behind it?

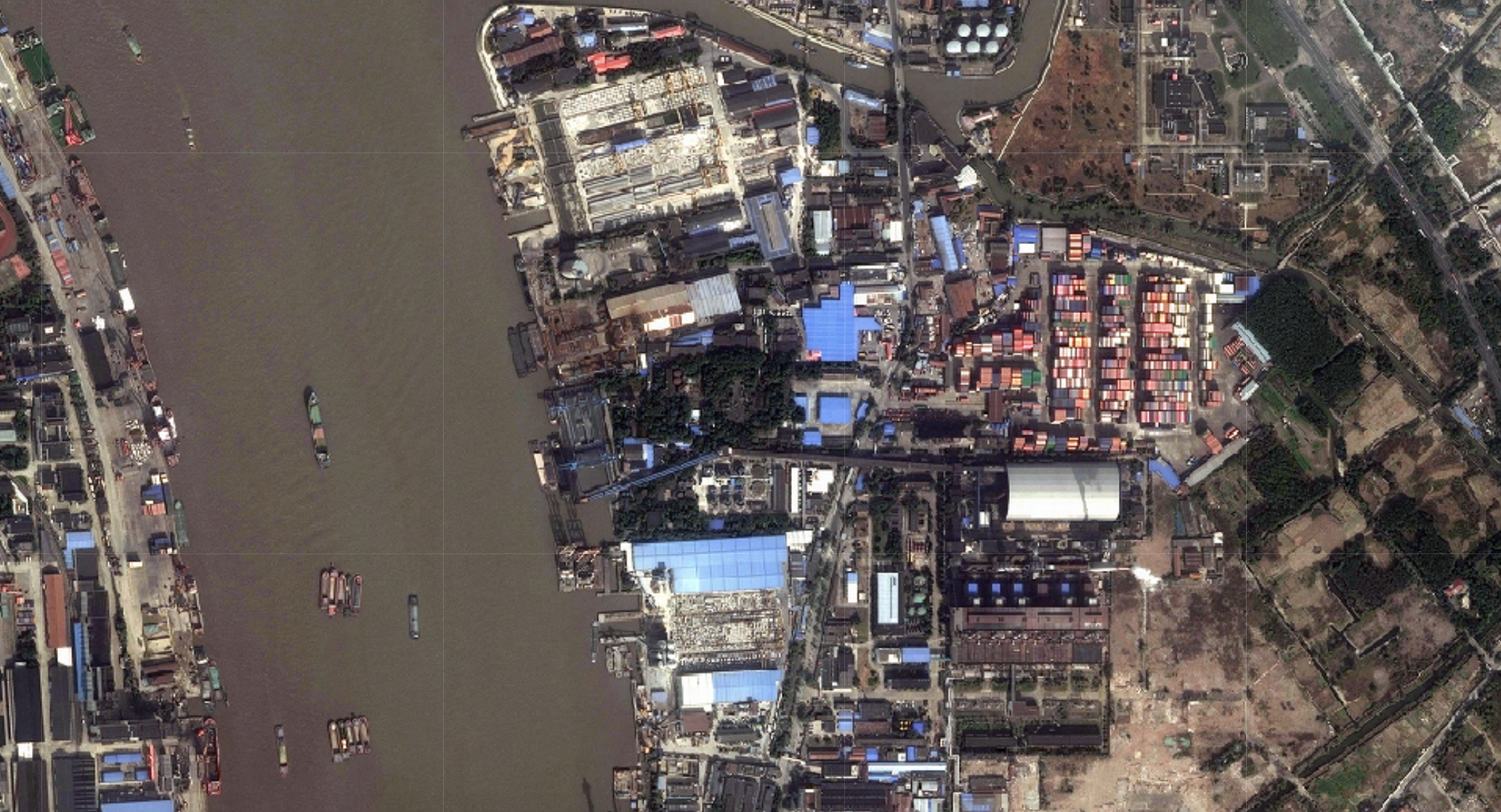

On a sultry summer night in July 2019, the MV Manukai was arriving at the port of Shanghai, near the mouth of the Huangpu River.

This busy tributary of the Yangtze winds through the city and includes the Bund, a historic waterfront area and tourist hot spot.

Shanghai would be the American container ship’s last stop in China before making its long homeward journey to Long Beach, California.

As the crew carefully maneuvered the 700-foot ship through the world’s busiest port, its captain watched his navigation screens closely.

By international law, all but the smallest commercial ships have to install automatic identification system (AIS) transponders.

Every few seconds, these devices broadcast their identity, position, course, and speed and display AIS data from other ships in the area, helping to keep crowded waterways safe.

The position data for those transponders comes from GPS satellites.

source : soar.earth

According to the Manukai’s screens, another ship was steaming up the same channel at about seven knots (eight miles per hour).

Suddenly, the other ship disappeared from the AIS display.

A few minutes later, the screen showed the other ship back at the dock.

Then it was in the channel and moving again, then back at the dock, then gone once more.

Eventually, mystified, the captain picked up his binoculars and scanned the dockside.

The other ship had been stationary at the dock the entire time.

When it came time for the Manukai to head for its own berth, the bridge began echoing to multiple alarms.

Both of the ship’s GPS units—it carried two for redundancy—had lost their signals, and its AIS transponder had failed.

Even a last-ditch emergency distress system that also relied on GPS could not get a fix.

Now, new research and previously unseen data show that the Manukai, and thousands of other vessels in Shanghai over the last year, are falling victim to a mysterious new weapon that is able to spoof GPS systems in a way never seen before.

Nobody knows who is behind this spoofing, or what its ultimate purpose might be.

These ships could be unwilling test subjects for a sophisticated electronic warfare system, or collateral damage in a conflict between environmental criminals and the Chinese state that has already claimed dozens of ships and lives.

But one thing is for certain: there is an invisible electronic war over the future of navigation in Shanghai, and GPS is losing.

The mystery deepens

Although the Manukai eventually docked safely, its captain was concerned enough to file a report later that day with the US Coast Guard’s Navigation Center, which collects reports of GPS outages worldwide.

“All [antenna] connections are secured and dry,” he wrote.

“There have been no other issues with these units. [I] suspect GPS signal jamming is occurring at this berth.”

In fact, something far more dangerous was happening, and the Manukai’s captain was unaware of it.

Although the American ship’s GPS signals initially seemed to have just been jammed, both it and its neighbor had also been spoofed—their true position and speed replaced by false coordinates broadcast from the ground.

This is serious, as 50% of all casualties at sea are linked to navigational mistakes that cause collisions or groundings.

When mariners simply lose a GPS signal, they can fall back on paper charts, radar, and visual navigation.

But if a ship’s GPS signal is spoofed, its captain—and any nearby vessels tracking it via AIS— will be told that the ship is somewhere else entirely.

Nor did the attacks stop once the Manukai was safely at its dock.

Several times that day, its AIS system reported that it was over three miles distant.

Half a world away from Shanghai, a tip landed on the Washington, DC, desk of a researcher at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), a nonprofit that analyzes global conflict and security issues.

The new tip, from a shipping industry source, suggested that somebody was spoofing GPS signals in Shanghai.

This was the first time that C4ADS had heard of widespread maritime spoofing not obviously linked to the Russians.

A few months earlier, the organization had published a report that detailed how Russia used GPS jamming in the Crimea, the Black Sea, Syria, Norway, and Finland.

It also contained evidence that a Russian mobile electronic warfare team had been disrupting GPS signals during President Putin’s public appearances.

After receiving the tip, C4ADS looked at the AIS data, which it purchased from a startup that records AIS broadcasts around the world.

Analysts noticed that the attacks had actually started the previous summer, increasing as the months rolled on.

The most intense interference was recorded on the very day in July that the Manukai’s captain reported difficulties, when a total of nearly 300 vessels had their locations spoofed.

While the disruption was affecting ships right across Shanghai, most of those spoofed were vessels navigating the Huangpu River.

source : Wikimedias commons

And this was very different from the hacking seen in Russian waters, where vessels were all spoofed to a single point.

The Shanghai data showed ships jumping every few minutes to different locations on rings on the eastern bank of the Huangpu.

On a visualization of the data spanning days and weeks, the ships appeared to congregate in large circles.

The C4ADS researchers had never seen circular patterns like this before.

Perhaps bugs or malware in the ships’ AIS or GPS systems were causing the effect?

To rule that out, they sought data from another form of transportation completely: cycling.

China has about as many bicycles as the rest of the world combined, with nearly 10 million in Shanghai alone.

Some of the city’s cyclists use smartphone fitness apps to track their rides.

One in particular, Strava, shares a global heat map of anonymized activities from the previous two years.

Zooming in to Shanghai, C4ADS analysts could see the same mysterious riverside circles glowing on Strava’s heat map.

The spoofing attacks were affecting all GPS devices, not just those on ships.

It was time to seek some outside help.

C4ADS shared its findings with Todd Humphreys, director of the Radionavigation Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin and a leading authority on GPS hacking.

Humphreys examined the data, but the closer he looked, the more confused he became.

“To be able to spoof multiple ships simultaneously into a circle is extraordinary technology.

It looks like magic,” he said.

In September, Humphreys showed a visualization of the data at the world’s largest conference of satellite navigation technology, ION GNSS+ in Florida.

“People were slack-jawed when I showed them this pattern of spoofing,” he said.

“They started to call it crop circles.”

A dangerous escalation?

To understand why the experts are baffled, consider how GPS works.

The US Air Force maintains a constellation of at least 24 Global Positioning System satellites orbiting the Earth; there are currently 31.

Each satellite broadcasts several complicated codes generated from its position and the current time, as measured by a super-accurate atomic clock on board.

Each clock is precisely synchronized with those on the other 30 satellites.

A GPS receiver detecting signals from one satellite can only calculate roughly how far it is from that satellite.

Add signals from a second satellite and it can narrow down its location considerably.

A third satellite allows it to locate itself at a given latitude and longitude, and a fourth establishes its elevation and the precise time.

Signals from more satellites increase the accuracy.

While GPS satellites broadcast several different signals intended for both military and civilian use, AIS relies on just one of them.

These signals are rather weak and can easily be drowned out—jammed—by even a modest transmitter at ground level.

They can also be spoofed by signals that mimic real GPS satellites but encode false time and position data.

In spoofing, every receiver within range usually receives the same fake signals, and thus believes itself to be in the same location.

While this is more serious than simply jamming the GPS signals, an alert captain would certainly notice if all the ships on the navigation screen suddenly jumped to the same place at the same time.

The Shanghai “crop circles,” which somehow spoof each vessel to a different false location, are something new.

“I’m still puzzled by this,” says Humphreys.

“I can’t get it to work out in the math.

It’s an interesting mystery.” It’s also a mystery that raises the possibility of potentially deadly accidents.

“Captains and pilots have become very dependent on GPS, because it has been historically very reliable,” says Humphreys.

“If it claims to be working, they rely on it and don’t double-check it all that much.”

On June 5 this year, the Run 5678, a river cargo ship, tried to overtake a smaller craft on the Huangpu, about five miles south of the Bund.

The Runavoided the small ship but plowed right into the New Glory (Chinese name: Tong Yang Jingrui), a freighter heading north.

The New Glory then lost control and veered into the riverbank, scattering pedestrians out for an evening stroll.

A small stretch of the bank collapsed, but luckily, no one was hurt.

While it’s not certain if it happened on this particular occasion, AIS data indicate that the New Glory was spoofed in Shanghai at least five times in the six months leading up to the collision, including less than two weeks before.

The data also show half a dozen attacks on other vessels in the city that same day.

Even Shanghai’s river police, the Huangpu Maritime Safety Administration (MSA), has been subjected to spoofing attacks on an almost daily basis.

The data show that one of its patrol boats was spoofed at least 394 times in nine months.

Soft gold

One possibility is that the crop circles are an escalation in a simmering electronic war in Shanghai that has put thousands of sailors, passengers, and even the river itself at risk.

For years, the MSA has been tracking and seizing ships that, while not jamming or spoofing GPS signals, have been hacking the AIS transponders that help keep Shanghai’s rivers and ports safe.

These ships have been cloning the AIS identities of other ships in order to slip in and out of the harbor unmolested by authorities.

The reason they’re doing this has to do with the cargo the New Glory was carrying when it ran aground: plain, everyday sand.

Chinese builders call it “soft gold.” Sand dredged from Yangtze River, which has the ideal consistency and composition for cement, helped fuel Shanghai’s construction boom in the 1980s and 1990s.

By the turn of the millennium, reckless sand extraction had undermined bridges, trashed ecosystems, and caused long stretches of the riverbank to collapse.

In 2000, Chinese authorities banned sand mining on the Yangtze completely.

The trade continued illicitly, however, expanding to include the illegal dredging of sand and gravel from the Yangtze estuary and the open seas near Shanghai.

By day, such ships look innocuous.

By night, they lower pipes to the riverbed to suck up thousands of tons of sand in a single session.

A full hold can be worth over $85,000.

So far in 2019, police along the Yangtze River have seized 305 sand-mining vessels and over 100 million cubic feet of sand—enough to fill over a thousand Olympic swimming pools.

The Shanghai MSA says illegal sand and gravel ships caused 23 wrecks along the Yangtze river in 2018, accounting for over half of all major accidents and killing 53 people.

Another "crop circle" that appears on Strava's Global Heat Map.

source : strava

Under the cover of darkness, AIS can be a useful tool for a sand thief.

Ships that are not equipped or licensed for sea travel, for example, have been known to clone the AIS systems of seafaring boats to avoid detection.

Nor are sand thieves the only users of hacked AIS technology.

In June this year, an oil tanker with a cloned AIS system rammed an MSA patrol boat in Shanghai while trying to evade capture.

Police believe that it had been smuggling oil.

“Ships like this type are usually driven by illegal interests,” said an MSA official.

“Once discovered, they will fight against law enforcement and attempt to escape, posing a great threat to the water navigation environment.

We will not tolerate such ghost ships.”

The question now is, are these previous AIS hacks connected to Shanghai’s new GPS circles in some way? An effective spoofing system could be worth millions to sand thieves.

By spoofing their own ships, they could glide invisibly into port.

Or by spoofing others and creating chaos, smugglers would give themselves a better chance of slipping through unnoticed.

It could be that the ability to generate spoofed circles is an escalation in technological know-how by the sand thieves.

Of course, it could be just a coincidence that the spoofed circles are occurring at a hot spot for AIS cloning.

Another possibility is that the Chinese state itself is testing out a new electronic weapon, perhaps for eventual use in disputed regions of the South China Sea.

While the data do not identify the culprits, they do contain some clues.

The center of the spoofing circles on the Huangpu is a factory owned by Sinopec Shanghai Petrochemical Company, a large chemical manufacturer.

But it is not clear whether the activity is associated with the facility or it’s just the location where the ships are being spoofed to.

“I don’t think it’s some rogue actor,” says Humphreys.

“It may be connected with some experimental capability that [the Chinese authorities] are trying to test.

But I’m genuinely puzzled how this is being done.”

source : sina.com

Links :

- TheDrive : New Type Of GPS Spoofing Attack In China Creates "Crop ... / China's Mysterious Spoofed GPS "Crop Circle" Has Something Interesting At Its Center

- BoingBoing : Sand thieves believed to be behind epidemic of Chinese GPS jamming / Sand thieves and unreliable GPS near the Port of Shanghai

- Aerospace Testing Int : What is spoofing and how can you ensure GPS security ...

- Rivieramm : Mysteries of the Middle East Gulf: proxies, drones and spoofing

- GeoGarage blog : The rise of cyber threats and GPS-jamming ... / Report: Russian GPS spoofing threatens ... / GPS jamming and spoofing: when good ... / Mass GPS spoofing attack in Black Sea? / Superyacht GPS spoofing experiment on the ...

No comments:

Post a Comment