- Copernicus : MyOcean colormaps

Saturday, October 17, 2020

CMES Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service viewer

Friday, October 16, 2020

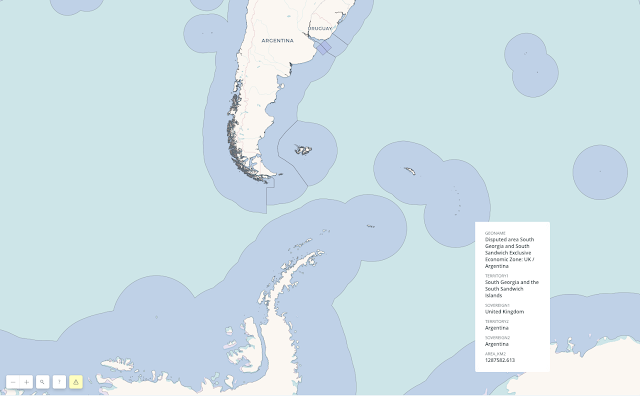

Argentina doubles in size, or so it claims

From The Economist

The government takes advantage of a UN ruling to extend the country’s territorial waters

Argentina’s president, Alberto Fernández, has plenty to worry about: a soaring covid-19 caseload and a depressed economy.

So it must have been delightful for the government to change the subject on September 21st by issuing a map showing that the country’s territory is nearly double its former size.

It illustrates the effect of a law Mr Fernández signed in August, which expands Argentina by 1.7m square km (650,000 square miles), an area three times the size of metropolitan France.

Argentina now bestrides South America and Antarctica, from the Tropic of Capricorn to the South Pole.

Its territory includes some of the world’s richest fishing grounds and possibly oil and gas.

The Falkland islands, which Argentines call the Malvinas, lie within it.

This is not entirely based on fantasy.

In 2016 the un’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (clcs) issued a ruling, based on the un Convention on the Law of the Sea, that fixes the edge of the vast shelf that juts out from Argentina’s coast.

There the seabed is shallow enough—less than 2,500 metres deep—to count as an extension of Argentina’s mainland.

The effect of the ruling is to extend Argentina’s territorial waters beyond the normal 200 nautical miles (370km).

Mauricio Macri, Argentina’s then-president, a conservative, celebrated the ruling in 2016 as a diplomatic victory but did not write it into law.

His priority was friendly relations with the rest of the world, including Britain.

In 1982 Britain fought a war to expel Argentina’s armed forces, which had invaded the Falklands that year.

Mr Fernández, a left-leaning Peronist, is more assertive.

The law he signed in August, and the borders on his map, take in far more than the area to which clcssaid Argentina was entitled.

In sending the territorial-expansion bill to Congress this year, Mr Fernández insisted on “Argentina’s claim to the Malvinas”, which has long been part of its law and is endorsed by nearly all Argentines.

The new official map shows South Georgia and the South Sandwich islands (also British), as part of Argentina, too, and adds areas that had it not claimed in law before.

The British are mainly interested in the water’s riches, Argentina’s government thinks.

That explains the “stubbornness of British colonialism”, suggested Daniel Filmus, the government’s secretary for the Malvinas, Antarctica and South Atlantic.

The map asserts Argentine sovereignty over the Antarctic peninsula, an ice-cream cone poking into the Weddell sea, which is also claimed by Chile and Britain.

In fact, the un commission avoided taking a position “in a case where a land or maritime dispute exists”.

The areas it awarded Argentina are a fraction of the country’s claim.

Argentina does not plan to try to reconquer the islands, but it does hope to use its interpretation of the commission’s ruling to press Britain to negotiate.

“The un is saying that the Malvinas is a matter of dispute,” contends an adviser to the president.

“The British always try to say there is no dispute over the islands.” Argentina’s foreign ministry put out a video calling for “dialogue” under un auspices.

Britain is unlikely to agree.

So Mr Fernández may have to be content with smaller satisfactions.

Argentine oceanographers are now in demand from other countries.

They are being consulted by specialists from Brazil, Germany, Denmark and even Chile, despite the peninsular dispute.

Schoolchildren will be taught that Tierra del Fuego, Argentina’s southernmost province, is now the country’s centre.

The country’s population of emperor penguins and leopard seals has greatly expanded.

In tough times, that may cheer Argentines up a bit.

- Durham Univ. : Argentina and UK claims to maritime jurisdiction in the South Atlantic and Southern Oceans

- MercoPress : Argentina's EEZ “flooded” by Chinese jiggers catching tons of squid

- GeoGarage blog : Turkey-Greece tensions: eastern ... / France expands its submarine domain by a ... / Brexit fishing map: The vast body of UK ... / Freedom of navigation and the Law of the Sea / As countries battle for control of North Pole ... / Turkey-Greece tensions: eastern Mediterranean claims in maps

Thursday, October 15, 2020

For sale: Shipwrecked whisky that spent decades underwater

If, however, there was a marquee item among the ship’s inventory, it was surely the whisky—264,000 bottles of it.

Some washed up on local beaches, and others were brought up by divers.

One of the latter, found by professional diver George Currie in 1987, is now up for sale at Scotland’s Grand Whisky Auction, where bidding will close on August 10, 2020.

At press time, the bottle was already going for nearly $8,000.

Though the auction house warns unequivocally that the “bottle is not suitable for human consumption,” the winning bidder will also be treated to a diving helmet and bricks from the ship itself.

Divers, including George Currie (bottom left), pose with lucky finds in 1987.

Divers, including George Currie (bottom left), pose with lucky finds in 1987.When SS Politician ran ashore it was wartime, rationing was in effect, and resources were scarce.

It’s not hard to imagine, then, how excited locals were to descend upon the wreckage and retrieve as many bottles as they could—“by any means necessary,” explains Beau Wallace, director of the Grand Whisky Auction.

According to a historical account in Scotch Whisky magazine, some men wore their wives’ clothing as they scavenged, so as not to stain their own with telltale spilled fuel.

Others reportedly traveled from as far away as the isle of Lewis, over 100 miles to the north, to get in on the action.

Less enthused were British authorities, who had not only lost a vessel but also the revenues (and duties) from the cargo on board.

Seeking restitution, they sent officers into villages to locate some of the missing goods, and some individuals were penalized.

A comic, fictionalized version of the events serves as the basis of Compton Mackenzie’s 1947 novel Whisky Galore, which was also made into a popular movie in 1949, and again in 2016.

The bottle currently on sale, says Wallace, represents “such a unique piece of history,”—or, at the very least, a unique piece of spirits history.

“Every Scotch drinker knows about Whisky Galore,” he says.

The story didn’t end, of course, with the hull’s destruction, or with the cinematic makeover.

There’s surely still some cargo floating around the Hebrides, and another diver had found eight bottles of his own, also in 1987.

(A pair of those sold for more than £12,000 in 2013.)

It was just “a lucky dive,” he says—all the luckier considering that the blasting of the ship was intended “to smash all the bottles.”

For years following the wreck, there were reports of water-damaged banknotes—10-shilling Jamaican bills held in the same area of the ship as the whisky—turning up ashore and changing hands in banks.

According to Scotch Whisky magazine, some 290,000 of these notes were on board before the wreck, worth more than $9 million today.

After the notes showed up in Liverpool, London, and even the United States (among other places), the government announced in 1958 that 211,267 of them had been accounted for.

That leaves tens of thousands that, for all we know, are still just drifting about.

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

How do augmented reality navigation systems work?

From Thetius by Nic Gardner

According to The Swedish Club, navigational accidents made up 30% of claims by type and 33% of claims by cost between 2014 and 2018.

Between 2013 and 2017, lack of situational awareness was cited as the most common cause of collisions (45%), and the second most common cause of the most expensive claims (27%).

But why is this?

If you’ve never stood a navigational watch, the bridge watchkeeper’s job appears straightforward: don’t hit anything.

However, as any bridge watchkeeper will tell you, it’s rarely that simple.

Many bridges are poorly designed, with incompatible equipment installed in inconvenient positions.

Watchkeepers have to break their visual lookout to refer to their equipment.

I’m sure many watchkeepers have fantasised about a unified system after a busy watch spent trying to match digital information with the view from the window.

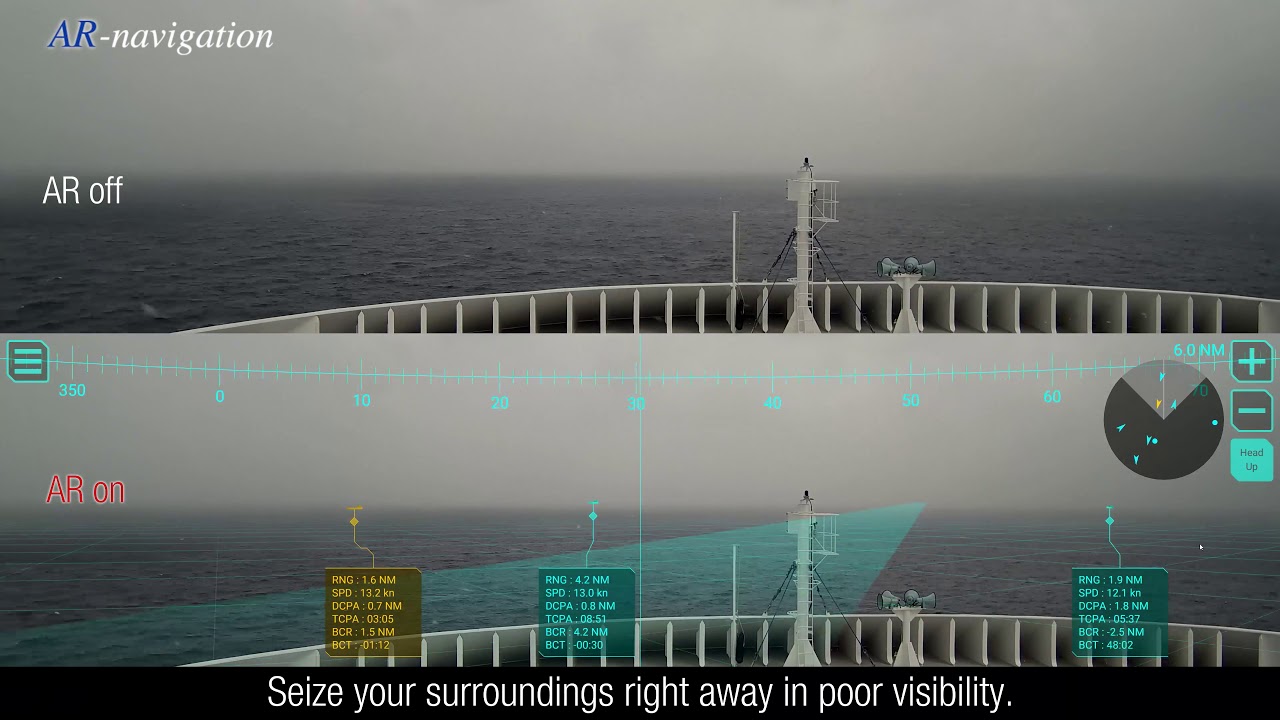

What if AIS and automated radar plotting aids (ARPA) information were floating in a bubble above other ships, and the course line, buoys, shallow patches and no-go zones were visible in the real world? Well, those systems exist: it’s called augmented reality (AR) navigation, and it’s here.

What’s augmented reality?

AR overlays digital content on the real world, either on a screen or using AR glasses.

Unlike in virtual reality (VR), AR can anchor digital information to real-world objects, even if they’re moving.

For example, rather than constantly cross-referencing radar and AIS, information about a target vessel can be displayed in an AR bubble near the target when you look out of the window.

If you know the smartphone game Pokemon Go, you know how AR works on a phone.

Car manufacturers are already building AR navigation systems into car windscreens, so it should be no surprise that it’s coming to ships.

You can read more about AR and related technology here.

What’s wrong with current navigational systems?

Endsley defines situational awareness as:

“The perception of the elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future.”

This is critical to safe marine navigation, but too often it’s an aspiration rather than a reality.

The inefficiency associated with task-switching is a well-studied phenomenon.

Even a well-rested person can only keep about seven different pieces of information in their working memory.

Yet the bridge of an average merchant ship has more aids to navigation than navigators of the past ever dreamed of.

Despite that, we expect watchkeepers to track information from assorted equipment, match that disparate information to the changing situation, process it, draw the correct conclusions, and act on their decisions.

All while monitoring three or four radios, filling in the logbook, and standing ready to respond to alarms.

It’s no surprise they sometimes miss something, with often catastrophic—and expensive—results.

Why AR navigation?

Source: Raymarine

Source: Raymarine

AR navigation systems make relevant information readily available in an accessible format at the point of use.

This reduces the cognitive load on the navigator and allows them to focus on the big-picture, rather than on the constant task-switching of gathering and cross-referencing information.

How does AR navigation work?

The AR system overlays relevant information on stabilised video images from a forward-facing camera.

Just as navigators can choose which information layers to display on an electronic chart display information system (ECDIS), AR navigation users can choose to display AIS, radar, ECDIS, gyrocompass and route information on their AR system.

AIS and radar targets change colour according to their threat level, and users can increase or decrease range and take bearings, just as with a radar or ECDIS.

The systems alert users to buoys, vessels and other targets of interest, displays shallow water, no-go zones and the planned track, and even includes information from other navigational instruments.

At a glance, the watchkeeper can check important voyage information such as the speed of other vessels, the closest point of approach and the time of closest point of approach of targets.

In restricted visibility, or at night in heavy coastal traffic, AR navigation systems offer a notable improvement in situational awareness, clearly indicating which lights are likely to be ships rather than shore lights, and where to look for targets in fog.

Who uses AR marine navigation systems?

Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (MOL) and Furuno collaborated to develop an AR navigation system.

In March 2019, MOL installed it on their car carrier Beluga Ace, and in October 2019 on their new very large crude carrier (VLCC) Suzukasan as a trial.

They’re planning to expand it into their twenty-one VLCCs, then to their energy transport fleet, including LNG and dry bulk carriers.

At the same time as MOL’s second trial, in October 2019 Furuno announced the Envision AR Navigation System.

Raymarine takes a different approach, offering their Raymarine Clearcruise AR as a free software upgrade for their existing Axiom multifunction displays rather than a standalone system.

Conclusion

AR navigation systems allow easy access to all relevant electronic information on a single screen.

This improves situational awareness, decreases cognitive load, and makes validating and cross-checking navigational information easier than ever.

Improved situational awareness leads to a reduction in navigational accidents, safer ships, and inevitable cost savings in repairs and insurance premiums.

Given the constant, valid reminders that navigational watchkeepers need to spend less time looking at equipment and more time looking out of the bridge windows, it’s hard to argue against a system designed to let them do exactly that.

Links :

- SeaNews : Augmented Reality in Shipping and Maritime Industry

- YachtingMonthly : Smart Navigation: From paper charts to augmented reality

- GeoGarage blog : US Navy and NASA collaborate on Augmented Reality displays / Augmented Reality (AR) in shipping / Tomorrow's cargo ships will use Augmented Reality to sail the ...

Tuesday, October 13, 2020

The island that humans can’t conquer

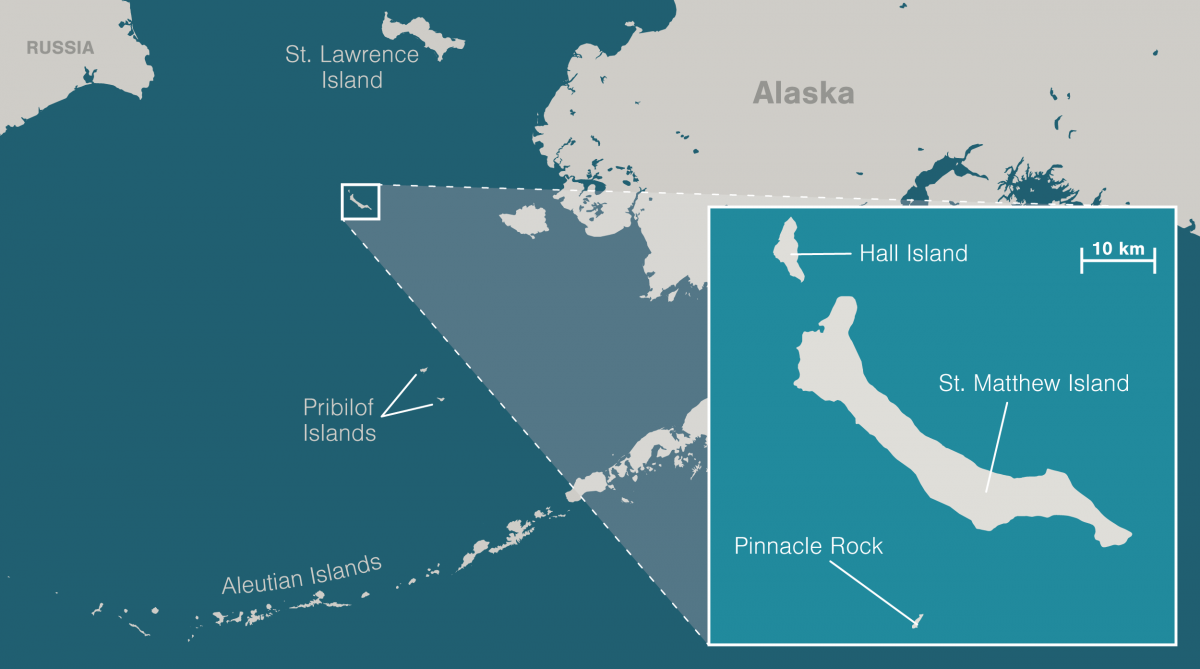

Matthew Island, in the Bering Sea.

From Hakai Mag by Sarah Gilman / Photos by Nathaniel Wilder

St. Matthew Island is said to be the most remote place in Alaska.

Marooned in the Bering Sea halfway to Siberia, it is well over 300 kilometers and a 24-hour ship ride from the nearest human settlements.

It looks fittingly forbidding, the way it emerges from its drape of fog like the dark spread of a wing.

Curved, treeless mountains crowd its sliver of land, plunging in sudden cliffs where they meet the surf.

To St. Matthew’s north lies the smaller, more precipitous island of Hall.

A castle of stone called Pinnacle stands guard off St. Matthew’s southern flank.

To set foot on this scatter of land surrounded by endless ocean is to feel yourself swallowed by the nowhere at the center of a drowned compass rose.

My head swims a little as I peer into a shallow pit on St. Matthew’s northwestern tip.

It’s late July in 2019, and the air buzzes with the chitters of the island’s endemic singing voles.

Wildflowers and cotton grass constellate the tundra that has grown over the depression at my feet, but around 400 years ago, it was a house, dug partway into the earth to keep out the elements.

It’s the oldest human sign on the island, the only prehistoric house ever found here.

A lichen-crusted whale jawbone points downhill toward the sea, the rose’s due-north needle.

Compared with more sheltered bays and beaches on the island’s eastern side, it would have been a relatively harsh place to settle.

Storms regularly slam this coast with the full force of the open ocean.

As many as 300 polar bears used to summer here, before Russians and Americans hunted them out in the late 1800s.

Evidence suggests that the pit house’s occupants likely didn’t use it for more than a season, according to Dennis Griffin, an archaeologist who’s worked on the archipelago since 2002.

Excavations of the site have turned up enough to suggest that people of the Thule culture—precursors to the Inuit and Yup’ik who now inhabit Alaska’s northwestern coasts—built it.

But Griffin has found no sign of a hearth, and only a thin layer of artifacts.

The Unangan, or Aleut, people from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands to the south tell a story of the son of a chief who discovered the then uninhabited Pribilofs after he was blown off course.

He overwintered there, and then returned home by kayak the following spring.

The Yup’ik from St. Lawrence Island to the north have a similar story, about hunters who found themselves on a strange island, where they waited for the opportunity to walk home over the sea ice.

Griffin believes something similar may have befallen the people who dug this house, and they sheltered here while waiting for their chance to leave.

Maybe they made it, he will tell me later.

Or maybe they didn’t: “A polar bear could have gotten them.”

In North America, many people think of wilderness as a place mostly untouched by humans; the United States defines it this way in law.

This idea is a construct of the recent colonial past.

Before European invasion, Indigenous peoples lived in, hunted in, and managed most of the continent’s wild lands.

St. Matthew’s archipelago, designated as official wilderness in 1970, and as part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980, would have had much to offer them, too: freshwater lakes teeming with fish, many of the same plants that mainland cultures ate, ample seabirds and marine mammals to hunt.

And yet, because St. Matthew is so far-flung, the solitary pit house suggests that even Alaska’s expert seafaring Indigenous peoples may never have been more than accidental visitors here.

Others who’ve followed have arrived with the help of significant infrastructure or institutions.

None remained long.

I came to these islands aboard a ship called the Tiĝlax̂ [TEKH-lah] to tag along with scientists studying the seabirds that nest on the archipelago’s cliffs.

But I also wanted to see what it felt like to be in a place that so thoroughly rejects human presence.

On this, the last full day of our expedition, as the scientists rush to collect data and pack up camps on the other side of the island, the pit house seems a better vantage than most to reflect.

I lower myself into the depression, scanning the sea, the bands of sunlight flickering across the tundra on this unusually clear day.

I imagine watching for winter’s sea ice, waiting for it to come.

I imagine watching for polar bears, hoping they will not.

You never know, a retired refuge biologist had said to me before I boarded the Tiĝlax̂.

“I would keep my eyes out.

If you see something big and white out there, look at it twice.”

Once, these islands were mountains, waypoints on the subcontinent of Beringia that joined North America and Asia.

Then the ocean swallowed the land around the peaks, hid them away in thick summer fogs, made them lonely.

With no people resident long enough to keep their history, they became the sort of place where “discovery” could be perennial.

Lieutenant Ivan Synd of the Russian navy, oblivious to the pit house, believed he was first to find the largest island, in 1766.

He named it for the Christian apostle Matthew.

Captain James Cook believed he discovered it in 1778, and called it Gore.

The whalers who came upon the archipelago later called it, simply, “the Bear Islands.”

Around the winter of 1809–1810, a party of Russians and Unangans decamped here to hunt bears for fur.

Depending on what source you consult, many of the Russians died of scurvy, while the Unangans survived, or some or most of the party perished when the sea mammals they relied on moved beyond the range of their hunts, or all were so tormented by polar bears that they had to leave.

Indeed, when naturalist Henry Elliott visited the islands in 1874, he found them swarming with bruins.

“Judge our astonishment at finding hundreds of large polar bears … lazily sleeping in grassy hollows, or digging up grass and other roots, browsing like hogs,” Elliott wrote, though he seemed to find them less terrifying than interesting and tasty.

After his party killed some, he noted that the steaks were of “excellent quality.”

Even after the bears were gone, the archipelago remained a difficult place for people.

The fog was endless; the weather, a banshee; the isolation, extreme.

In 1916, the Arctic power schooner Great Bear ran afoul of the mists and wrecked on Pinnacle.

The crew used whaleboats to move about 20 tonnes of supplies to St. Matthew to set up a camp and wait for help.

A man named N. H. Bokum managed to build a sort of transmitter from odds and ends, and climbed each night to a clifftop to tap out SOS calls.

But he gave up after concluding that the soggy air interfered with its operation.

Growing restless as the weeks passed, men brandished knives over the ham when the cook tried to ration it.

Had they not been rescued after 18 days, Great Bear owner John Borden later said, this desperation would have been “the first taste of what the winter would have brought.”

US servicemen stationed on St. Matthew during the Second World War got a more thorough sampling of the island’s winter extremes.

In 1943, the US Coast Guard established a long-range navigation (Loran) site on the southwestern coast of the island, part of a network that helped fighter planes and warships orient on the Pacific with the help of regular pulses of radio waves.

Snow at the Loran station drifted up to around eight meters deep, and “blizzards of hurricane velocity” lasted an average of 10 days.

Sea ice surrounded the island for about seven months of the year.

When a plane dropped the mail several kilometers away during the coldest time of year, the men had to form three crews and rotate in shifts just to retrieve it, dragging a toboggan of survival supplies as they went.

The other seasons weren’t much more hospitable.

One day, five servicemen vanished on a boat errand, despite calm seas.

Mostly, the island raged with wind and rain, turning the tundra to a “sea of mud.”

It took more than 600 bags of cement just to set foundations for the station’s Quonset huts.

The coast guard, worried how the men would fare in such conditions if they were cut off from resupply, introduced a herd of 29 reindeer to St. Matthew as a food stock in 1944.

But the war ended, and the men left.

The reindeer population, without predators, exploded.

By 1963, there were 6,000.

By 1964, nearly all were gone.

Winter had taken them.

These days, the Loran station is little more than a towering pole anchored by metal cables to a bluff above the beach, surrounded by a wide fan of debris.

On the fifth day of our week-long expedition, several of us walk the sagging remains of an old road to the site.

Near the pole that still stands, a second has fallen, a third, a fourth.

I find the square concrete pillars of the Quonset huts’ foundations.

A toilet lies alone on a rise, bowl facing inland.

I pause next to a biometrician named Aaron Christ, as he shoots photos of a pile of rusting barrels that shriek with the scent of diesel.

“We’re great at building wondrous things,” he says after a moment.

“We’re terrible at tearing them down and cleaning them up.”

And yet, the tundra seems to be slowly reclaiming most of it.

Monkshood and dwarf willow grow thick and spongy over the road.

Moss and lichen finger over broken metal and jagged plywood, pulling them down.

At other sites of brief occupation, it’s the same.

The earth consumes the beams of fallen cabins that seasonal fox trappers erected, likely before the Great Depression.

The sea has swept away a hut that visiting scientists built near a beach in the 1950s.

When the coast guard rescued the Great Bear crew in 1916, they left everything behind.

Griffin, the archaeologist, found little but scattered coal when he visited the site of the camp in 2018.

Fishers and servicemen may have looted some, but what was too trashed for salvage—perhaps the gramophone, the cameras, the bottles of champagne—seems to have washed away or swum down into the soil.

The last of the straggling reindeer, a lone, lame female, disappeared in the 1980s.

For a long time, reindeer skulls salted the island.

Now, most are gone.

The few I see are buried to their antler tips, as if submerged in rising green water.

Life here grows back, grows over, forgets.

Not invincibly resilient, but determined and sure.

On Hall Island, I see a songbird nesting in a cache of ancient batteries.

And red foxes, having replaced most of St.

Matthew’s native Arctic foxes after crossing on sea ice, have dug dens beneath the Loran building sites and several pieces of debris.

The voles sing and sing.

The island is theirs.

The island is its own.

The next morning dawns dusky, light and clouds stained sepia by smoke blown from wildfires burning in distant forests.

I spot something big and white as I walk across St. Matthew’s flat southern lobe and freeze, squinting.

The white begins to move.

To sprint, really.

Not a bear, as the retired biologist had hinted, but two swans on foot.

Three cygnets trundle in their wake.

As they turn toward me, I spot a flash of orange porpoising through the grass behind them: a red fox.

The cygnets seem unaware of their pursuer, but their pursuer is aware of me.

It veers from the chase to settle a couple of meters away—scraggly, gold eyed, and mottled as the lichen on the cliffs.

It drops to its side and rubs luxuriantly against a rock for a few minutes, then springs away in a possessed zigzag, leaving me giggling.

After it’s gone, I kneel to sniff the rock.

It smells like dirt.

I rub my own hair against it, just to say “hey.”

As I continue on, I notice that objects in the distance often appear to be one thing, then resolve into another.

Ribs of driftwood turn out to be whale bones.

A putrid walrus carcass turns out to be the wave-pummeled rootball of a tree.

Unlikely artifacts without stories—a ladder, a metal pontoon—occasionally jag from the ground, deposited far inland, I guess, by storms.

When I close my eyes, I have the vague feeling that waves roll through my body.

“Dock rock,” someone will call this later: the sensation, after you have spent time on a ship, of the sea carried with you onto land, of land assuming the phantom motion of water beneath your feet.

It occurs to me that to truly arrive on St. Matthew, you have to lose your bearings enough to feel the line between the two blur.

Disoriented, I can sense the landscape as fluid, a shapeshifter as sure as the rootball and whale bones—something that remakes itself from mountains to islands, that scatters and swallows signs left by those who pass across.

I consider the island’s eroding edges.

Some cliffs in old photos have fallen away or buckled into sea stacks.

I look at the few shafts of sun out on the clear water, sepia light touching dark mats of kelp on the Bering’s floor.

Whole worlds submerged or pulverized to cobble, sand, and silt, down there.

A calving of land into sea, the redistribution of earth into unknowable futures.

A good place to remember that we are each so brief.

That we never stand on solid ground.

The wind whips strands of hair out of my hood and into my eyes as I press my palms into the floor of the pit house.

It feels firm enough, for now.

That it’s still visible after a few centuries reassures me—a small anchor against the dragging currents of this place.

Eventually, though, I get cold and clamber out.

I need to return to my camp near where the Tiĝlax̂ waits at anchor; we’ll be setting course south back over the Bering toward other islands and airports in the morning.

But first, I aim overland for a high, gray whaleback of ridge a few kilometers away that I have admired from the ship since our arrival.

The sunlight that striped the hills this morning has faded.

An afternoon fog descends as I meander over electric green grass, then climb, hand over hand, up a ribbon of steep talus.

I top out into nothingness.

One of the biologists had told me, when we first discussed my wandering alone, that the fog closes in without warning; that, when this happened, I would want a GPS to help me find my way back.

Mine is malfunctioning, so I go by feel, keeping the steep drop of the ridge’s face on my left, surprised by flats and peaks I don’t remember seeing from below.

I begin to wonder if I have accidentally gone down the ridge’s gently sloping backside instead of walking its top.

The fog thickens until I can see only a meter or two ahead.

Thickens again, until I, too, vanish—erased as completely as the dark tracery of path I left through the grass below soon will be.

Then, abruptly, the fog breaks and the way down the mountain comes clear.

Relieved, I weave back through the hills and, on the crest of the last, see the Tiĝlax̂ in the placid bay below.

The ship blows its foghorn in a long salute as I lift my hand to the sky.

Links :

Monday, October 12, 2020

A new ship’s mission: Let the Deep Sea be seen

A giant new vessel, OceanXplorer, seeks to unveil the secrets of the abyss for a global audience

In 2014, when crude oil was selling for more than $100 a barrel, the cost of a new drill ship for oil exploration could run to $100 million.

So when the price of oil crashed, Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates, an investment firm in Westport, Conn., saw an opening.

In 2016, he bought a lightly used oil drilling ship at a very attractive price and transformed it into his dream — a vessel for big science, big technology and big storytelling.

Mr. Dalio’s aim is to help Homo sapiens connect more intimately with the ocean, with what he calls “our world’s greatest asset.”

Without hyperbole, OceanXplorer will change the game of ocean exploration (and storytelling), now and forever.

OceanXplorer is now making its operational debut, after years of rebuilding, upgrading and outfitting.

So is Mr. Dalio, 71, as a new kind of entrepreneur.

He sees his glistening, high-tech ship as a superstar not only of oceanic research but of video production, nature television shows and livestreaming events that will open the abyss to an unusually wide audience.

“It’s going to change things,” in part by inspiring a new generation of ocean explorers, Mr. Dalio said.

Schoolchildren in classrooms will be able to guide the ship’s undersea robot through the primal darkness, uncovering riots of life.

“This isn’t a dream,” Mr. Dalio said in a recent interview.

“This is it.”

At 286 feet from bow to stern, OceanXplorer is nearly the length of a football field.

Side-to-side thrusters can hold it steady in pounding waves.

It can house 85 crew members and explorers.

Its hangar can hold three miniature submarines for taking humans into the sunless depths.

It has two undersea robots, one that runs on a tether and one smart enough to roam on its own.

At the bow, an automated system watches for whales, scanning the chop to avoid collisions.

Credit...OceanX

The vessel’s gear and agenda draw on a decade of experience that Mr. Dalio gained while traveling the globe with scientists on Alucia, his smaller research ship.

Like the new one, it featured mini submarines with bubblelike hulls of clear plastic that give the divers stunning panoramic views

In 2013, Mr. Dalio was exploring the deep Pacific with scientists from Yale University and the American Museum of Natural History when, in pitch darkness, a camera was flashed.

The surrounding creatures proceeded to light up in bioluminescent waves.

“It was like a fireworks display,” Mr. Dalio recalled.

“Everything was responding.

It was unbelievable.”

Vincent Pieribone accompanied Mr. Dalio on that voyage.

He is an author of “Aglow in the Dark: The Revolutionary Science of Biofluorescence” and a neuroscientist at the Yale School of Medicine who uses the chemistry of ocean biofluorescence to study human nerve impulses.

Mr. Dalio talked him into serving as vice chairman of OceanX, an undertaking of Dalio Philanthropies to explore the ocean.

As the organization’s chief scientist, Dr. Pieribone helped rig the new ship for science investigations and directed much of its exploratory planning.

“I walked on the boat and was literally in tears because of all these things we were able to do,” he said recently.

“It’s like something out of a Bond movie.”

Mr. Dalio is one of a growing number of billionaire philanthropists seeking to reinvent themselves as patrons of social progress through science research.

According to Forbes, he has an estimated net worth of $16.9 billion, making him one of the world’s richest individuals.

His firm, Bridgewater Associates, is regularly described as the world’s largest hedge fund.

Mr. Dalio said his ocean journey had begun while he was growing up on Long Island as the only son of a professional jazz musician — his father — and a stay-at-home mother.

On television, he loved watching the sea adventures of Jacques Cousteau, the French oceanographer.

Then, in his early 20s, Mr. Dalio learned how to scuba dive and, ever since, has been going deeper.

A turning point came in 2011 as he deepened his relationship with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

The complex of shingled houses and brick laboratories is famous for devising Alvin, a submersible that was the first to illuminate the Titanic and to carry scientists down to the hot springs of the global seabed.

The dark ecosystems teem with crabs, shrimp and tube worms.

Mr.Dalio was thinking of buying the Alucia when a team of Woods Hole experts used the vessel and an undersea robot to find the shattered remains of Air France Flight 447, which in 2009 had vanished over the South Atlantic with 228 passengers.

Other search teams had failed, and Mr. Dalio saw the 2011 success as an indication of the field’s exploratory promise.

“It was a needle in a haystack,” he said of the jetliner hunt.

“I was shocked and elated.”

Almost immediately, the pair of vehicles made a major discovery.

The giant squid — huge and slimy, its tentacles lined with sucker pads, its big eyes unblinking — is a fixture of horror fiction, including Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” But it had long eluded science.

A 1994 book by Richard Ellis, “Monsters of the Sea,” called the creature so mysterious that “no one has seen a giant squid feeding — in fact, no one has ever seen a healthy giant squid doing anything at all.”

In the summer of 2012, off Japan, Alucia and its bubble subs hosted a team of scientists who found and filmed one of the beasts.

The discovery made a global splash in 2013 on newscasts and documentaries.

Mr. Dalio’s youngest son, Mark, was then an associate producer at National Geographic’s television network.

Fascinated by the squid hunt, he persuaded his father to finance a multimedia venture, Alucia Productions, that would chronicle Alucia’s research.

In 2017, the ship appeared in the BBC documentary series “Blue Planet II,” which was credited with producing a surge in applications for the study of marine biology.

By that point, Mr. Dalio had purchased the drill ship and was turning it into a suite of mobile laboratories for deep science and public education.

For expert advice, he turned not only to his son, to Woods Hole and to Dr. Pieribone of Yale but to the film director James Cameron.

The Hollywood mogul knew a great deal about marine science and technology, having plunged to the ocean’s deepest spot in an undersea craft of his own design that he then donated to Woods Hole.

Among other things, Mr. Cameron suggested banks of lighting that would illuminate not only the sea creatures being studied but the experts examining them.

Last year, he told Variety that the giant ship, as a set, would illuminate the passion that drove exploration of the ocean.

“You are going to have adversity and psychological challenges,” he said.

“The crew will be disappointed, the explorers will be disappointed.

But for every moment there’s a setback or challenge, there’s going to be that moment of discovery.

You want to take the audience on that roller coaster journey, because that’s what exploration is all about.”

Credit...Andy Mann

The ship’s giant hangar is designed to hold not only the compact bubble subs the ship has already been outfitted with but larger undersea craft as well.

A few of them, including Mr. Cameron’s, can plunge down nearly seven miles to the ocean’s deepest recesses.

Their spherical hulls are typically made not of plastic but of superstrong metals such as titanium that can resist the crushing pressures.

Another innovation on OceanXplorer lets the bubble subs send video signals from their cameras to the surface on beams of light, allowing not only rapid consultations with experts aboard the vessel but the live broadcasting of exploratory findings.

“There’s nothing like OceanXplorer,” said Rob Munier, head of marine facilities and operations at Woods Hole.

“It’s geared toward taking the concept of great science and great media to the next level.”

The ship’s inaugural voyage is to be profiled in “Mission OceanX,” a six-part series for National Geographic television.

BBC and OceanX Media (previously Alucia Productions) are producing the series, and Mr. Cameron is an executive producer.

OceanXplorer, after being reconfigured and outfitted in Europe, is now in sea trials.

Filming for the television series is to begin early next year.

Mr. Dalio has long called investigations of the oceans more important than space exploration — doing so, for instance, in his best-selling 2017 book, “Principles: Life and Work.”

“The return on investment is so much greater,” he said in the interview, referring to ocean exploration.

A riddle of the modern world, Mr. Dalio added, is why understanding and protecting the ocean gets relatively little money, time and effort compared with outer space.

“If you think about the excitement and the importance, there’s no comparison.”

Links :

- SuperYacht Times : OceanXplorer: Inside the world’s most advanced research vessel

- National Geographic : See inside a marine science laboratory unlike any other: the ...

- Deeper Blue : OceanX Launches New OceanXplorer Research Vessel ...