From The Economist by Oliver Franklin-Wallis

The ocean floor is the Earth’s last great uncharted region.

Oliver Franklin-Wallis joins the man descending to the bottom of the deepest trenches on the planet

The Submarine DSV Limiting Factor bobbed in the Atlantic swell.

Gleaming white, with a hull the shape of a hip flask, its lights gave the water an otherworldly glow.

Stooping slightly inside the crew compartment—a snug titanium sphere 1.5 metres across with two white leather seats and three portholes the size of dinner plates—Victor Vescovo looked into the gloom.

Eight kilometres below him, at the floor of the Puerto Rico Trench, lay his destination: the Brownson Deep, the deepest point in the Atlantic.

Vescovo braced as a wave rocked the hull.

Tall and athletic, with a blond ponytail and white beard, Vescovo is a Texan private-equity investor.

He had scaled the tallest mountain on every continent and skied the last degree to both Poles, making him one of only a few dozen people to have completed the “Explorer’s Grand Slam”.

Now, at 53, there were no mountains higher.

Every continent was mapped and visible on Google Earth.

He wanted to make history.

The only way was down.

The deep ocean is the Earth’s last great unexplored frontier.

Below the surface, sunlight fades.

Soon you are in total darkness.

It is cold.

Communication is difficult.

At 100 metres the pressure is ten times that on the surface; at 2,000 metres, it is great enough to collapse a US Navy submarine.

Apart from Vescovo’s, fewer than ten manned craft are currently able to operate below 3,700 metres, the ocean’s average depth, and no other active ones can go below 7,500 metres.

At that point, submariners enter what oceanographers call the Hadal Zone, derived from Hades – the Ancient Greek underworld.

The ocean’s deepest point, the Pacific’s Challenger Deep, is nearly 11km down.

When Vescovo set out, only three men had ever seen it.

Twelve have walked on the Moon.

No one had ever reached the deepest points in all five oceans.

So in 2015 Vescovo hired Triton Submarines, a company that makes private submersibles, to build him a craft that could take him to them.

Three years in development, at a cost of $49m, the Limiting Factor (named for a spacecraft in Iain M.

Banks’s sci-fi Culture novels) was the most advanced private submersible ever built.

Vescovo also bought a ship, the DSSV Pressure Drop, which he fitted out with an advanced sonar-imaging system to map the seafloor in unprecedented detail.

He called his year-long expedition “The Five Deeps”, and invited a documentary crew from the Discovery Channel to chronicle the historic endeavour.

But now, with the Puerto Rico Trench yawning beneath him, the whole enterprise was in jeopardy.

For five days the Limiting Factorhad failed to launch.

The first dive was called off when water began to trickle in from the inner hatch.

Leaks on submarines are not the catastrophe you might assume; as the submarine descends, the increasing pressure tends to close any gaps tight.

But at Hadal depths, that wasn’t worth the risk.

On the second attempt, the leak persisted.

A third attempt.

The hatch was still leaking.

There were other problems too.

The ballast system, designed to control buoyancy, didn’t work properly.

Cameras broke.

Alarms sounded in the cockpit.

Still they dived.

Then calamity struck.

At 1,000 metres, a frangible bolt—which was supposed to detach explosively in the event of power loss to shed weight—broke off.

The bolt had been securing the submarine’s $350,000 robotic arm, designed to collect rock and sediment samples.

Vescovo watched through the porthole as it slumped to the sea floor.

To make things worse, as the injured submarine was lifted from the water, a violent swell smashed it against the ship’s stern, damaging a set of propellers.

Back on board the ship, Patrick Lahey, the president of Triton, felt crushed.

A sun-weathered Canadian who used the F-word with flair, Lahey had spent decades building submersibles for wealthy clients.

The Limiting Factor was the pinnacle of his career.

He threw the documentary crew out of the submarine hangar while his engineers surveyed the damage.

It was in dire shape.

Rebuilding it on land would take days.

Stewing in his cabin Vescovo considered cancelling the whole venture.

The ship had to return to port in three days’ time to resupply.

A lengthy refit of the submarine could mean missing their weather window in the Antarctic, delaying the whole expedition by a year and costing millions of dollars.

A producer in London asked one of the documentary crew when the sub would be operational: “When pigs fly,” supposedly came the response.

That evening the expedition crew gathered around the long central table in mission control.

The mood was tense.

Sonar depth charts lit up a bank of displays overhead.

After talking through the risks with Lahey and his team, Vescovo agreed to one last attempt.

If that didn’t work he would call off the expedition.

Triton’s engineers worked through the night.

They replaced the hatch seal with a new, softer rubber, fixed the camera and rewired faulty circuits.

Out on the water the next morning Vescovo mentally ran through his final pre-dive checklist.

He examined the hatch above him.

Not a drop was coming in.

In front of him two tablet computers displayed the sub’s key readings.

On his right, red and green lights on the central power console glowed reassuringly.

Electrical systems: good.

The radio crackled with chatter from mission control.

Communications: good.

Above Vescovo’s forehead a stuffed penguin—a gift from his sister—perched on a bank of white oxygen tanks that would sustain him through the six-hour dive and days longer, if necessary.

Life support: good.

The final confirmation came over the radio: “LF…you are free to dive.”

Vescovo initiated the dive sequence.

The LF’s ballast tanks began filling with seawater, taking on weight.

Slowly, the sub began sinking below the surface.

Vescovo settled in as the ocean outside darkened through every shade of blue.

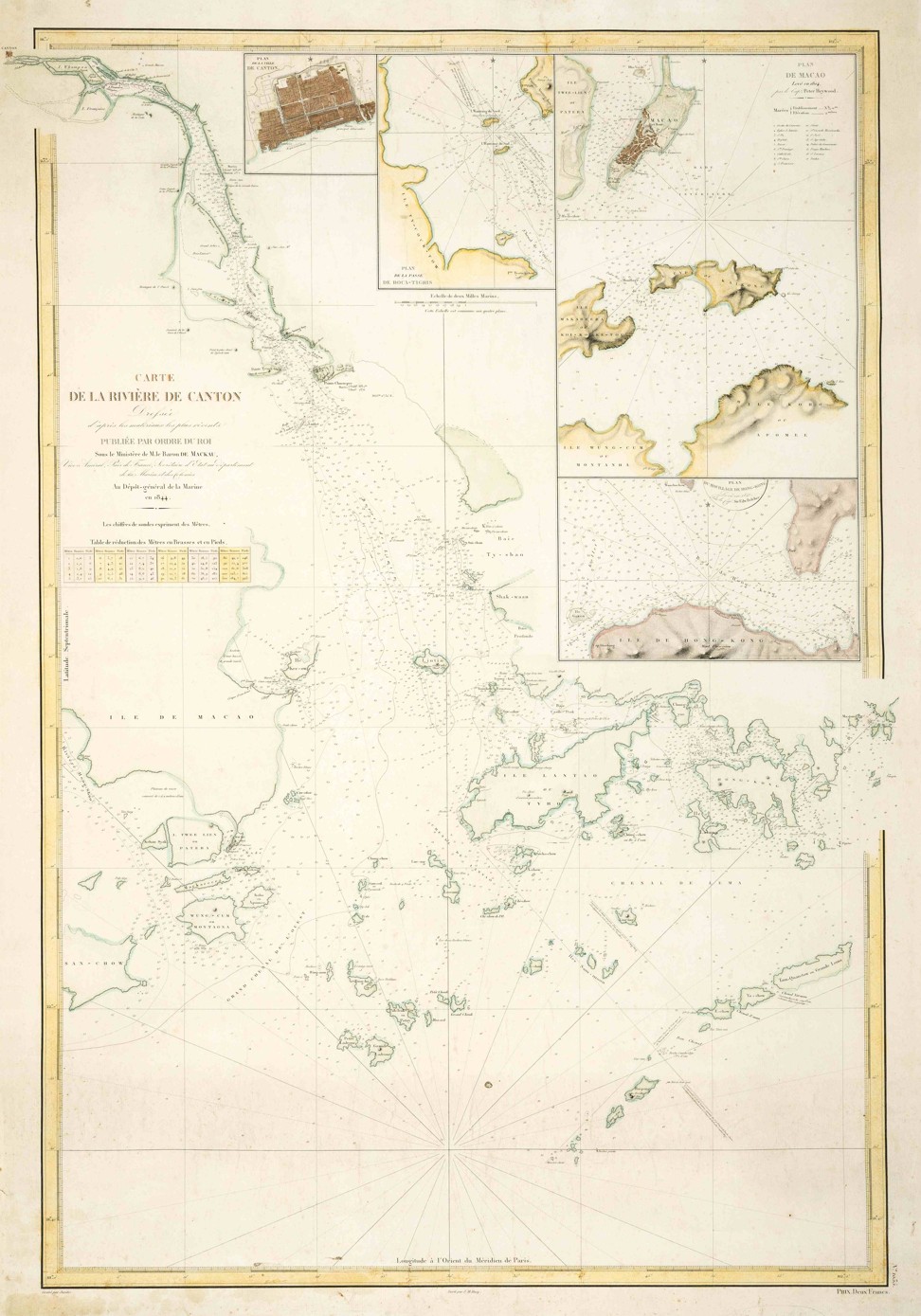

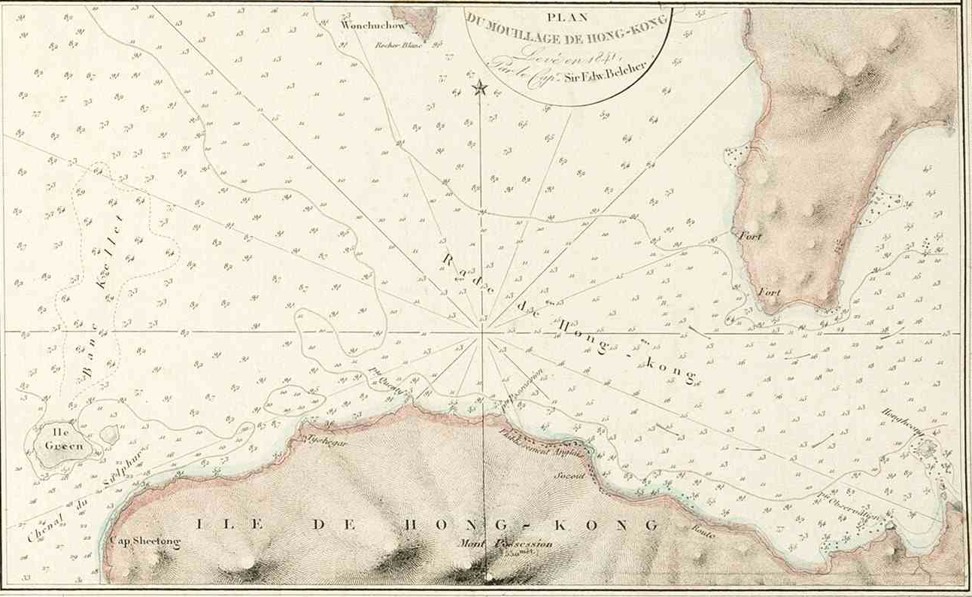

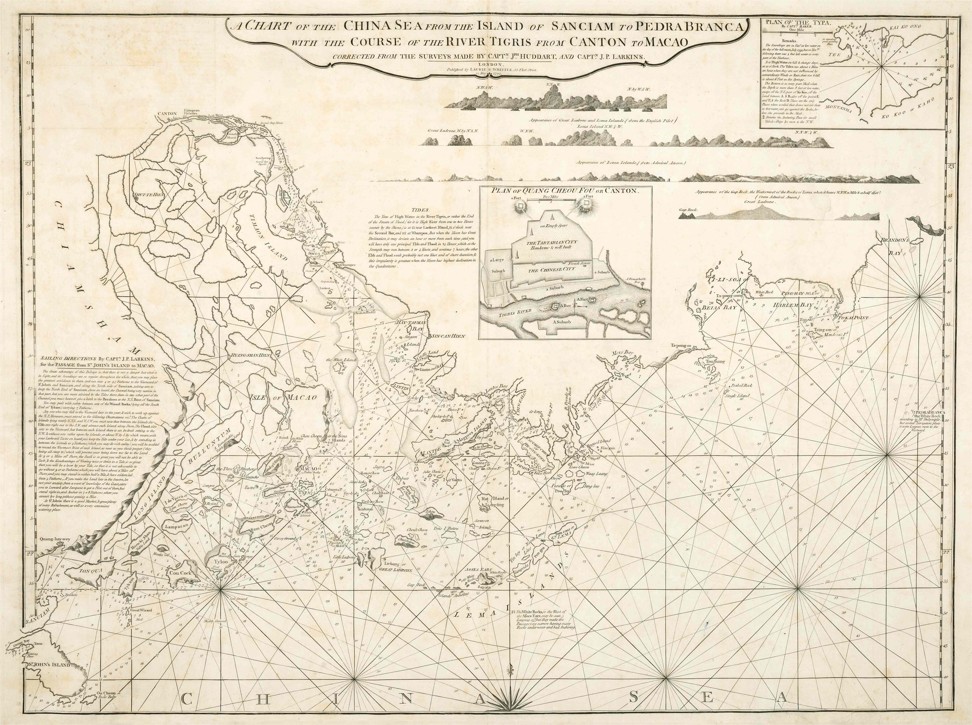

The ocean covers nearly three-quarters of the Earth’s surface yet more than 80% of it remains unexplored.

Radar doesn’t penetrate deep water, so accurate depth soundings must be made by ships with high-resolution sonar.

It’s slow, boring work.

The maps we do have are at best an approximation.

New discoveries are common.

The search for Malaysian Airways flight MH370 turned up previously undiscovered undersea volcanoes and trenches.

We have more accurate maps of Mars than we do of two-thirds of our own planet.

Vescovo wanted to be an explorer from “the beginning of thought”.

Growing up in Dallas, he often disappeared alone on his bike for hours.

His father, who worked in real estate, would find Vescovo miles from home, unfazed.

He was a voracious reader and excelled at school (“I tested well,” he said).

He studied economics and political science at Stanford and took a Masters at MIT.

Shortly after graduating, while backpacking in Kenya, he discovered mountaineering.

“I loved the fact that it combines physical stamina—just being able to take punishment—as well as technical knowledge,” he said.

Vescovo had always enjoyed maps and data, ways to bring order to the world.

(In 2006 he self-published a book, “The Atlas of World Statistics”.) He found climbing as much an intellectual challenge as a physical one.

A mountain was a test that required solving with his whole body.

In 2002, after a few years in management consultancy, Vescovo co-founded Insight Equity, a private-equity firm.

It specialised in turning around industrial companies.

“We put in a lot of our own money into the deals, which meant that when they went well, we did very well,” he said.

It went very well.

He bought three Lamborghinis and the house next door in which to fix them up.

As a boy, Vescovo had wanted to become an air-force pilot.

Poor eyesight ruled out a combat career, but he learned to fly anyway: light aircraft, helicopters and, eventually, his own private jet.

Later, he joined the navy reserve.

For 20 years he periodically took time out from his career to serve.

When he wasn’t working Vescovo tackled ever tougher ascents: Denali in Alaska; Aconcagua in Argentina; Elbrus, the highest mountain in Russia.

In 2010 he attempted Everest.

It was May, late in the climbing season, and bad weather rolled in as Vescovo’s group approached the summit.

“We couldn’t see more than 20 metres,” he told me.

They reached the top, but the view was shrouded in blinding snow.

After brief rest and pictures—in one you can see Vescovo, his beard encrusted with ice, holding a “Beat Cal” flag in tribute to his alma mater—the party started back down.

“I was…annoyed doesn’t begin to describe it,” he told me, his disappointment still audible.

Nevertheless, he had beaten the mountain.

“Mountaineering teaches a very important lesson, which is live to fight another day,” he said.

Everest conquered, he set out for the Poles.

That was a different type of gruelling experience: desolate, alien.

In the pitiless cold it felt like an entire continent was against him.

“The North Pole is much harder,” he says.

“It’s moving, so you go to sleep and when you wake up you’re farther away than when you started.

If anything gets wet, or you sweat, you cannot dry it out.

It’s impossible.”

Afterwards he began to look for his next project.

In 2012 James Cameron, who directed “Titanic”, had dived the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench in the Pacific with his own custom-built submarine, the Deepflight Challenger.

Vescovo also heard that Richard Branson, a British entrepreneur, had quietly shelved his plan to dive the deep-ocean trenches when he discovered his submarine would be rendered unusable after a single dive.

“I started doing some research and realised, wow, it’s never been done,” Vescovo said.

By then Vescovo was rich.

But the money didn’t interest him.

“When you get to about eight figures, that’s when you start going, how much money do I really need?” He hadn’t married or had children; work always seemed to get in the way.

He had a girlfriend but no dependents, other than his three black Belgian Schipperkes, Ivan, Nikolai and Mishka.

“I’m not trying to be the wealthiest guy.

I’m competitive, but not in that way.

I don’t have a family that I need to provide for.” In the Five Deeps expedition he saw an opportunity to join the ranks of great explorers—Roald Amundsen, Neil Armstrong—and advance understanding of the deep ocean at the same time.

Plus, he said, it was “a nice cool adventure, that I could afford”.

As the Limiting Factor descended into the Puerto Rico Trench, the gold-rimmed depth gauge slowly rotated before Vescovo’s eyes: 1,000 metres, 2,000 metres, 3,000 metres.

Though the vessel was descending fast, Vescovo could feel barely any movement.

Only the temperature changed, as the titanium hull plummeted farther from the sun.

Every 15 minutes Vescovo reported on his depth, heading and oxygen levels.

The hydrophone screeched whenever a message came in.

Vescovo jotted down instrument readings and the occasional observation in his blue leather notebook.

He had prepared tirelessly for this moment.

During the sub’s development, Triton had built a full-scale simulator in Vescovo’s Dallas garage.

Every weekend for months his girlfriend would laugh as he climbed inside to practise dives for hours on end.

He had honed his discipline in the navy.

Piloting the sub, he said, “isn’t exactly like flying, but it rhymes”.

The maxims were the same: live by the checklist; carve the routines into muscle memory; never get complacent.

“There shouldn’t be heroics,” he said.

“If there are heroics on an expedition, someone screwed up.

It’s just like war: when you see a soldier with a whole bunch of medals, it’s like, ‘boy, you must have had some shitty commanders’.” Before each attempt, he and Lahey would joke: let’s have a boring dive today.

As the sub reached the sea floor, the first thing Vescovo noticed was the brightness.

The silt was mixed with glass-like microalgae called diatoms, and, reflecting the bright light emitted by the sub’s LEDs, it dazzled him.

The water was spectacularly clear: a sparse, pristine landscape stretched in every direction, interrupted only by a few rocks and dark mats of seaweed, fallen from above.

Vescovo radioed to the surface.

“Depth: 8,375 metres, at bottom”.

He switched on the documentary cameras and began to explore.

Deep-ocean trenches are volatile landscapes, formed when one tectonic plate is forced under another.

The consequences of movement can be catastrophic: an earthquake at the bottom of the Indian Ocean on Boxing Day 2004 triggered a tsunami that killed over 227,000 people.

“They’re very active environments,” Heather Stewart, the Five Deeps team’s resident geologist, told me.

“Epic 3,000-metre cliffs, active faults, volcanoes.

If these features were on land, they would be World Heritage sites.”

Until the mid-19th century, it was widely thought that the deepest level of the ocean was barren – that the pressure was too great for life to survive.

Advances in technology have proved this hypothesis wrong.

Deep-sea vents are breeding grounds for chemosynthetic bacteria, which get their energy from chemical reactions, feeding trenches that teem with life: ghostly, translucent snailfish; grazing sea cucumbers; writhing, prawn-like amphipods.

“There’s been a whole community that seems to occupy a huge part of our planet and no one had known about it because no one ever goes deep enough,” said Alan Jamieson, the expedition’s lead scientist, a gruff Scot.

Jamieson literally wrote the book on the Hadal Zone.

(It’s called “The Hadal Zone”.)

Vescovo spent more than an hour navigating the bottom.

For company he talked to the documentary cameras in the cockpit.

Though he couldn’t see much beyond the glare in the portholes, the expedition also made its first contribution to ocean science: the landers, which make observations and take samples from the deepest waters, documented four new species of amphipod in the Puerto Rico Trench.

That evening, as the sunset daubed orange across the horizon, the Limiting Factor broke the surface of the Atlantic.

On board, the expedition crew cheered and embraced each other.

At least one of them cried.

Lahey called the dive “probably the proudest moment of my life, other than the birth of my kids”.

Vescovo grinned as he climbed out of the hatch and into the waiting dinghy.

“One down,” he said.

Six months later, I boarded the Pressure Drop in Tonga, in the South Pacific.

By then the expedition had already completed four of the five deeps.

They had overcome icebergs and roaring seas to dive the South Sandwich Trench in the Southern Ocean.

In April the Limiting Factor became the first manned vessel to explore the Java Trench in the Indian Ocean, 7,192 metres down.

(The Indonesian government refused to grant a dive permit, so the ship turned off its tracking beacons, went dark and dived anyway.)

In May, Vescovo had beaten James Cameron’s all-time depth record, reaching 10,928 metres in the Pacific’s Challenger Deep.

In the submarine hangar the Triton crew were working on the Limiting Factor.

Suspended in its steel cradle, the submersible looked like a spacecraft, every line designed for efficient vertical travel.

The outer flotation hull was scratched and dented, scars from more than two-dozen dives.

“This thing takes more abuse than the space shuttle,” said Kelvin McGee, the sub’s stout, irrepressible operations manager, patting the side proudly.

Another engineer, drenched in oil, was repairing the robotic arm.

“You can’t step into Walmart and buy those parts,” said Lahey.

“Everything has to be made, designed, tested.” The titanium for the crew compartment was 9cm thick, he explained, milled to a 99.933% perfect sphere to evenly distribute pressure.

The tolerances were so fine that the forge in LA had to develop a new manufacturing method.

Any less could risk structural weakness and a fatal implosion.

When Vescovo first contacted Triton in 2015, he just wanted something basic: “a vehicle that could get to the bottom and back up”.

Lahey convinced him to add a second seat and the robotic arm which, though it increased the price considerably, would make the sub an asset for deep-ocean science by enabling researchers to collect geological and biological samples from the trench floor.

It would also make the sub more attractive to eventual buyers once the expedition was over.

“This is not a one-shot craft,” Lahey told me.

“It wasn’t intended to do Victor’s hero dives”—as several of the crew sarcastically called them—“and then be retired to a museum.”

Lahey has spent his life in the water: first as a commercial diver, then as a sub pilot, finally as an engineer.

He has seen manned submarines fall out of favour in oceanography, with the rise of underwater drones.

But for Lahey, drones offer a superficial experience of ocean life.

“Imagine doing your bird-watching through a drone,” he said dismissively.

Being in a submarine, floating over a reef, he said, “changes you.

It’s quiet, it’s peaceful.

There’s beautiful colours, it’s teeming with life.

It really is sublime.”

There was a hum of motors.

The arm was working again.

“That’s fucking beautiful! An extra ration of rum for you this evening,” Lahey said.

The engineer smiled.

“Oh, I’m drinking a bottle tonight!”

By then the expedition had become a tight-knit operation.

The crew had bonded over months at sea (“One great big dysfunctional family!” Lahey joked) and at mealtimes they would tell war stories: memorable dives, previous expeditions, near misses.

Vescovo talked about Everest or his tours in the navy reserves.

At times it seemed as though he saw those as his true career, and investment as the hobby.

Each dive began in the same way: Vescovo would wake before dawn, don his blue flight suit, pack his usual lunch—a tuna sandwich, a Coke and crisps—and climb down the narrow chute into the cockpit, before launching into the darkness.

Descent and ascent took up to four hours each way.

There was no toilet, only a bottle (“or as we pilots like to call them, ‘range extenders’”).

To stave off boredom between communications checks, Vescovo watched films or history documentaries on his phone.

But once at depth he barely had time to appreciate his surroundings.

“When you’re at the bottom, a minute feels like ten seconds. When you’re on the way up, a minute feels like 20 minutes,” he said.

He no longer worried about his own safety.

“It’s a titanium sphere that’s bolted together.

It would take God himself to try and crack that thing,” Vescovo said.

“The most dangerous thing would be if there is some major collision and pieces of the foam sheared off. Then all of a sudden, I’m negatively buoyant and I can’t get back up. But the possibility is just so remote.”

After each dive Jamieson fell into a routine: empty the landers’ traps, photograph and measure each specimen—“length it, weight it, sex it”—and take white-tissue samples, before freezing them.

Deep-sea crustaceans have evolved for Hadal depths and pressures, so “on the surface, they’re basically cooking”.

The Hadal Zone makes up less than 1% of the ocean by area, but, viewed in cross-section, it accounts for almost half the depth.

“And it gets ignored,” Jamieson said.

Maps decorated the walls of his office, a narrow room just off mission control.

On a shelf lay two rubber ducks, from his son back home in Scotland.

He showed me some videos from the deeps.

The footage was full of life: in Java, thousands of tiny translucent sea cucumbers grazed in the sand like cattle.

Fish swarmed the landers’ bait traps.

“Other than tropical lagoons, where else do you see such abundance?” Jamieson marvelled.

With the expedition approaching its final leg, the emotional highs of the early accomplishments had faded and left a slight sense of regret.

The Challenger dives had made headlines worldwide.

But it wasn’t their achievements that had caught the world’s imagination.

Instead, every headline was about the revelation that Vescovo had filmed a plastic bag at the bottom.

Vescovo and the crew were livid.

It wasn’t even true.

Vescovo had filmed something plastic in the Java Trench—they don’t know what it was—and a press release had mixed it up with Mariana Trench.

Soon the mistake echoed around the world.

“That fucking plastic bag,” said Jamieson.

“It wasn’t even the right trench!”

Four deeps completed, and the Limiting Factor had also failed to collect any sediment or water samples, in part because of Vescovo’s insistence on diving solo.

Although the arm had been replaced after Puerto Rico, it was too difficult for one person to operate it and also pilot the sub.

The plan had been to follow each solo attempt with a two-person science dive, but several of these had been scrapped due to the submarine’s early technical challenges.

In the Southern Ocean Vescovo had accidentally turned the cameras off, resulting in no footage at all.

“Half the science is already dead,” Jamieson said, irritated.

For him, every “hero dive” was a missed opportunity.

“There’s no actual scientific basis for [them] at all,” Jamieson said.

The Tonga Trench is the second-deepest on the planet but it had never been explored in detail.

Vescovo hoped it might prove to be even deeper than the Mariana Trench.

If so, it would be a historic discovery.

As we sailed over the trench, the sonar scanned the seabed, building up a detailed picture of the chasm below.

While engineers tinkered with the sub, Vescovo mostly worked alone in his cabin.

In his office the expedition’s leader, Rob McCallum, watched the weather charts intently.

A low-pressure system was mustering off New Zealand, threatening the dive.

“It could get a little sporty,” he said.

A veteran of countless dive expeditions, McCallum was used to managing wealthy clients.

“It’s my job to be brutally honest,” he explained.

The job required tact, and patience.

“I’m on a crusade against ego. Ego gets people in trouble.”

That evening McCallum gathered the crew in mission control.

The map of the trench illuminated two large monitors.

Sonar readings had dashed Vescovo’s hopes for the all-time record: the bottom was shallower than the Challenger Deep by less than 100 metres.

Nonetheless, Vescovo would dive the deepest point.

Then, weather allowing, the plan was to dive to a spectacular cliff face accompanied by Stewart, the expedition’s geologist.

It was to be Stewart’s first dive, making her the first woman to travel to the Hadal Zone.

The weather, however, threatened to end the trip early.

“If we do just one dive, it will be the dual dive,” Vescovo said, to some surprise.

But the next day, with the low-pressure front dithering to the south, he decided to go ahead solo.

The launch went smoothly.

But after about an hour on the bottom, Vescovo reported to the surface that the Limiting Factor’s battery levels were unusually low.

A few minutes later Lahey received a text message over the communicator: Vescovo’s systems were shutting down.

Frustrated, he aborted the dive.

Later, it would emerge that water had broken into one of the sub’s junction boxes, shorting a circuit and melting a hole in the side.

Though Vescovo was safe inside the cockpit, the damage was extensive (“The deepest submarine fire ever!” Vescovo joked).

Repairs would take days.

The second dive was cancelled.

Afterwards, Stewart disappeared to her cabin, clearly devastated.

Vescovo seemed to regret the outcome.

“I feel bad for her, though it is what it is.” There would be other chances, he said.

And a sub fire at depth could have been far worse.

“It’s an expedition,” Vescovo said.

McCallum nodded.

“Not a cruise.”

Later, in a quiet moment, I asked Vescovo why he insisted on diving solo.

“It’s just how I am. I can’t answer it any more than that. I really can’t,” he said.

“I like climbing alone, I like flying alone. I like doing things by myself, I guess, because it’s a more intense experience. On the other side I’d know it was me that was responsible for it and I took care of things. I put myself in that position with no reliance on anyone else.”

Despite setbacks, the expedition had still made significant contributions to ocean science.

Jamieson had catalogued several possible new species of amphipods, at least one new species of snailfish and a mysterious stalked ascidian—a gelatinous cloud-like creature with a long tail—that seemed to fly like a kite in the current.

After the Java and Mariana records, he’d accompanied Vescovo on science dives, finally visiting the undersea realm he’d studied for a decade.

(It was, he said with typical understatement, “fucking awesome”.)

The sonar team had produced the first detailed maps of several trenches, which Vescovo pledged to share with the Seabed 2030 project, an international effort to map the sea floor.

“First people to do Java, San Cristobal, Santa Cruz, Tonga.

Even if we do one dive, at least we’ve got something to go on.

It does have an extraordinarily high value to it,” Jamieson said.

“It’s just a shame,” he added, that they hadn’t done more.

Ultimately, Vescovo planned to sell the submarine and the Pressure Drop to a scientific body.

For Lahey and McCallum, the legacy of the expedition wasn’t the records but the Limiting Factor itself.

“Victor, he’s a peak bagger. For him, it’s about ‘I got there first, I got there fastest.’ We don’t belittle that, [but] you know, I couldn’t give a shit,” McCallum told me.

“The thing that’s important to me is that this is the first time in history that humankind has had a vehicle that can go to any place in the ocean.

What it means is that there is now nothing in the ocean that cannot be revisited and recovered.”

In August, the Limiting Factor was scheduled to dive the Molloy Deep, the last of the Five Deeps, in the only ocean it hadn’t yet explored: the Arctic.

Afterwards, the ship would sail to London for a congratulatory ceremony at the Royal Geographic Society.

There the crew would disperse: Jamieson and Stewart to write up their discoveries, the Triton contingent to work on commercial submarines, McCallum to his next client.

Vescovo was already thinking about another adventure.

Those who make history often find that returning to normality takes the greatest toll.

Buzz Aldrin talked of “the melancholy of all things done”.

Vescovo claimed not to be interested in fame.

“I’m not on Facebook, not on Instagram, not into social media.

I don’t understand why people are,” he said.

He seemed to crave a less transient form of recognition.

The site of Vescovo’s dive in the Southern Ocean was previously unmapped, and, in keeping with oceanographic tradition, Vescovo hoped to name it the Factorian Deep, after his submarine – finally putting his achievement on the maps that he’d loved as a boy.

“I was raised Episcopalian, but I’m probably more Zen Buddhist,” he told me.

The ship’s mess, which Vescovo had decorated with old film posters – “Submarine”, “20,000 Leagues under the Sea” – was deserted.

The ship rocked quietly.

“I know that everything is impermanent. I know immortality isn’t celebrity and so therefore I do not seek it. Instead, I seek what I can hold, which is the experience of doing all these things. I desire to live intensely.”

Vescovo, who has lost both parents and an older sister, thinks about mortality a lot.

“So many people in this world, they don’t know it, but they’re half asleep. They’re seeking to be comfortable. That’s not enough. I want to be awake. I’m not here very long, and I’m going to die one day, and I don’t want to go through it looking back and going ‘Gosh, I was asleep this whole time.’

I guarantee, you’re in a submarine at 10,000 metres, circuit-breakers going off behind your head, you’re awake.

Or flying a helicopter and you do your first autorotation with no power, you are bloody awake.

When you’re climbing Everest in the storm, and it is cold, and you’re passing dead bodies and still going up, you are awake.”

There was one last frontier he had yet to visit: space.

“There’s Branson, there’s Bezos, and there’s Musk. They’re all close,” he said.

Vescovo is far less wealthy than Bezos or Musk.

If he does go, it will be in one of their ships, as a paying customer.

The next age of discovery will not play out under the flags of nations but the logos of tech billionaires.

“These guys have a ton more money than I do.

What I never get is: why didn’t they do it themselves? If I was Musk I would be the first guy in that freakin’ rocket,” he said, excitedly.

“I guess they don’t even see themselves as the pilot.

I couldn’t see any other way.”

Links :