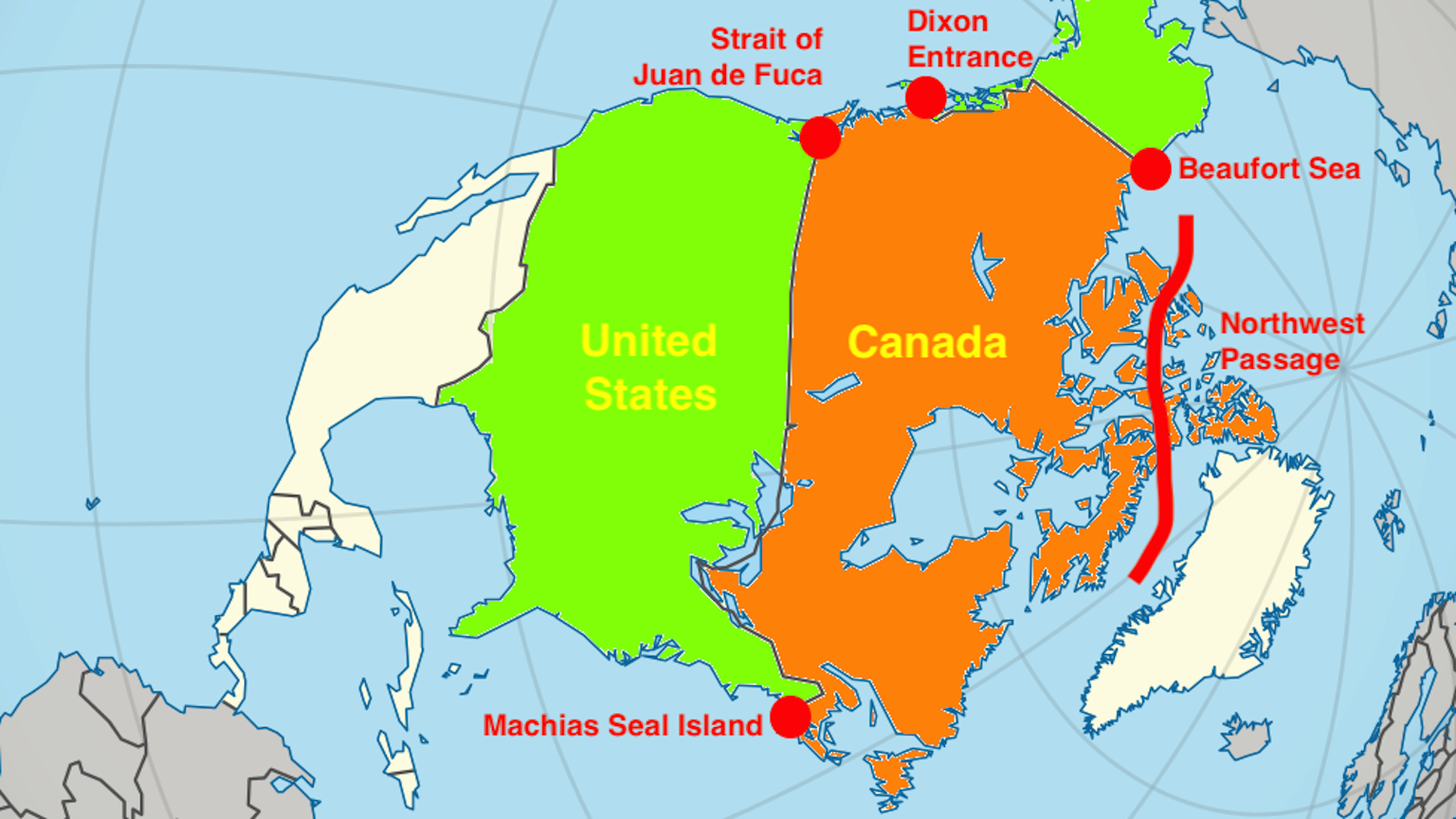

Five conflicts with history – and a future.

Credit: TUBS, CC BY-SA 3.0 / image processed by Ruland Kolen From BigThink by Frank Jacobs

All of these conflicts have a long history. They may also have a long future.- U.S.-Canada relations are mostly friendly, but both countries do not agree on everything.

- In these five places, they even argue about where the border between them should be.

- Those conflicts have been around for a long time, but that does not mean they cannot get worse.

It is often called the longest undefended and peaceful border in the world, and for its 5,525 miles (8,891 km) over land, the U.S.-Canada border is just that.

At sea, it is a different story.

There are five maritime locations where Canada and the U.S. have very different opinions over who owns what.

If ever the friendly relations between both countries turn frosty, it could very well be over one or more of these disputed areas.

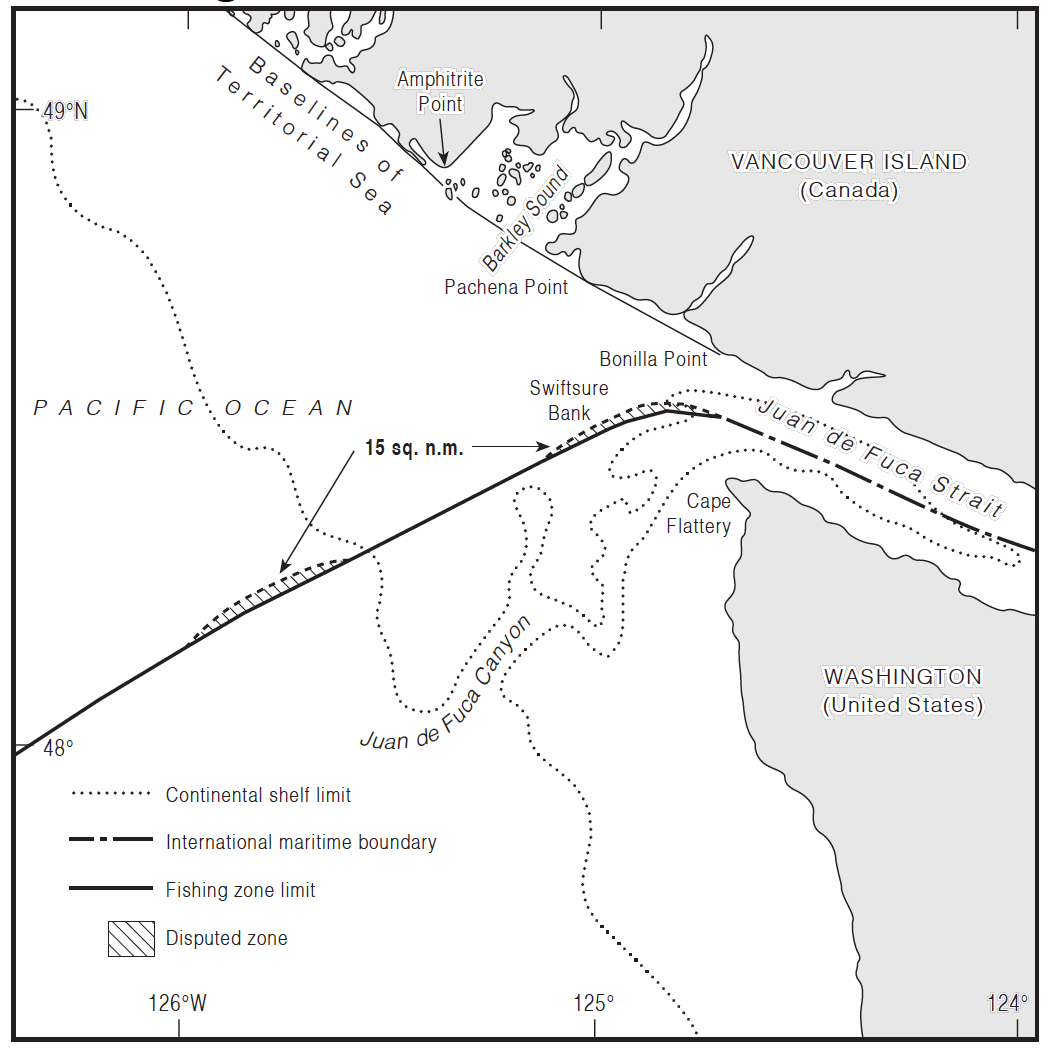

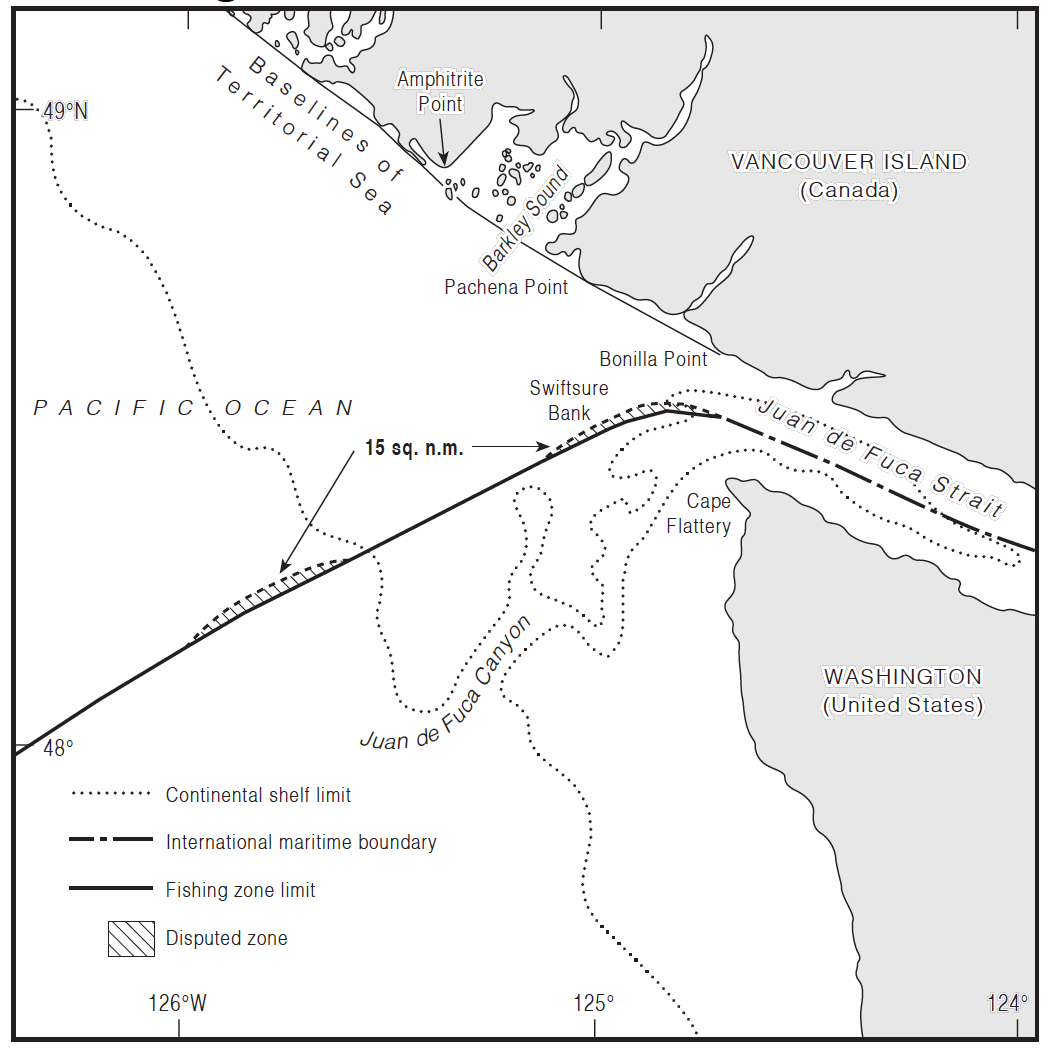

The Strait of Juan de Fuca: a three-way fight over equidistance

Two small slivers adding up to no more than 15 square nautical miles.

Credit: David H. Gray, “Canada’s Unresolved Maritime Borders” (via IBRUat Durham University).Ioannis Phokas was born in Greece but served the Spanish king, under a name more suitable to the Spanish palate: Juan de Fuca.

In 1592, he claimed to have found the fabled Strait of Anian.

Legend held that this channel connected the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Like many other legends animating discoverers and explorers across the Americas, this one too mistook wishes for reality.

De Fuca’s name would have melted back into obscurity if English sea captain Charles Barkley, exploring the Pacific Northwest in 1787, had not spotted some similarities with descriptions from de Fuca’s expedition.

Today, his name resonates across the region.

There is a strait named after Juan de Fuca, and derived from that a tectonic plate and an undersea ridge, as well as a park on Vancouver Island, and… a territorial dispute.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca separates Vancouver Island in British Columbia (Canada) from the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State (U.S.).

The border between both countries runs straight down the middle of the strait.

No problem here: it is the bit out to sea that is under dispute.

The disagreement between the U.S. and Canada is not about principle.

Both countries agree the border here should be equidistant between them.

The problem is: equidistant from where?

Each side uses slightly different base points, resulting in small differences in the borderline.

To complicate matters, the provincial government of British Columbia has rejected both the Canadian and American borderlines and the entire principle of equidistance.

It argues for the principle of natural prolongation, claiming that the appropriate boundary is the submarine canyon (also named Juan de Fuca).

Although that would mean a better border for British Columbia, the Canadian government is loath to give up the principle of equidistance, which could cost it dearly in other areas.

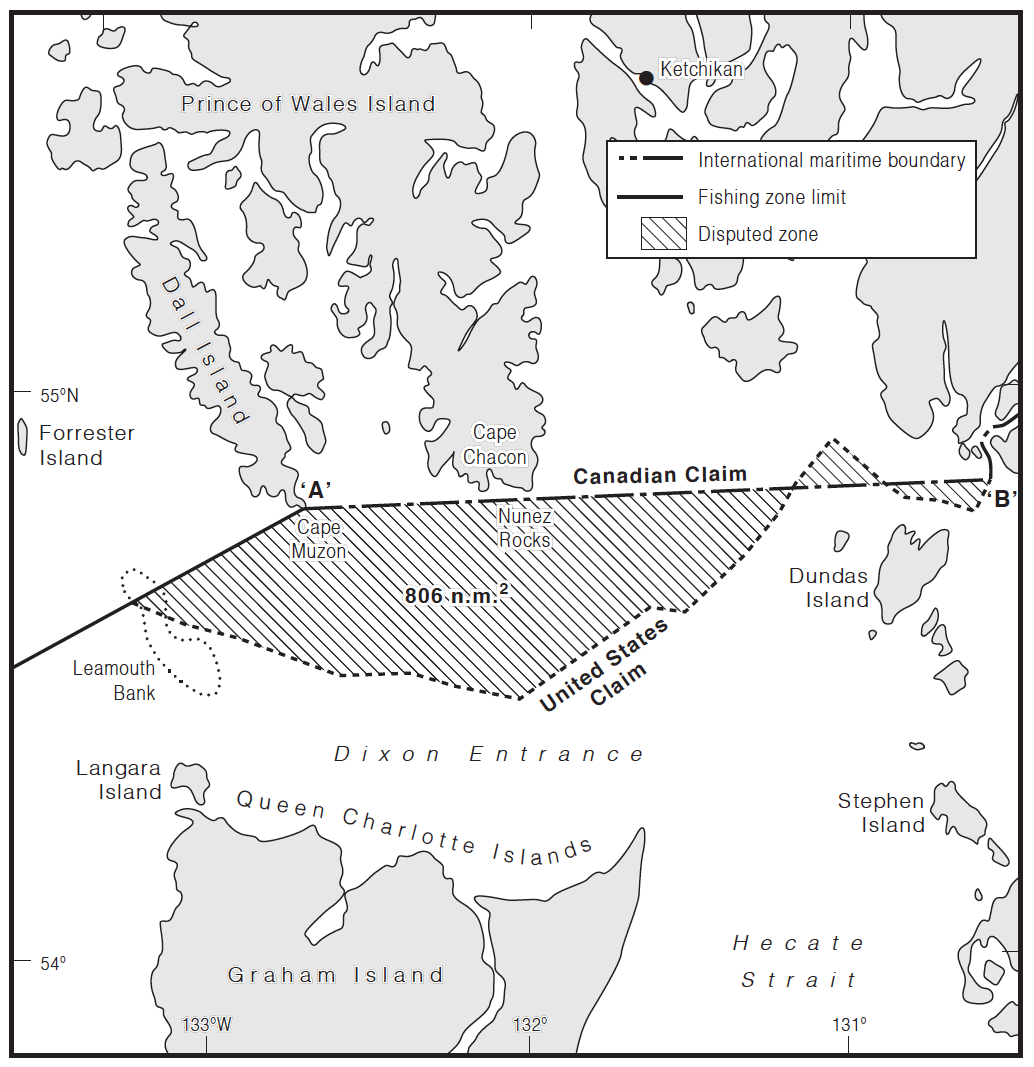

The Dixon Entrance: where the U.S. is north and Canada south

The largest patch of the three shown here measures 806 square nautical miles.

Credit: David H. Gray, “Canada’s Unresolved Maritime Borders” (via IBRUat Durham University). Canada is north of the United States, right? At the Dixon Entrance, it is the other way around.

North of this body of water lies Prince of Wales Island.

Despite its royal name, the island is part of the United States.

It is also the southernmost point of Alaska’s panhandle.

To the south of the Dixon Entrance lies Canada’s Haida Gwaii archipelago, known as the Queen Charlotte Islands until 2010.

The archipelago’s northernmost island is still referred to as Graham Island, perhaps because its Haida name is a bit of a mouthful: X_aaydag_a Gwaay.yaay linag_waay in X_aayda Kil.

The waters in between are rich with fish, attracting orcas, albatrosses, and humans.

In pre-contact times, local tribes feuded over access to these marine resources.

The neighbors are still in disagreement, but their names now are the U.S.

and Canada.

The present conflict has its roots with yet another set of rivals: Russia and Britain.

Squint, and you can spot today’s border between Alaska and Canada in the map annexes to the 1825 Treaty of St Petersburg.

Signed halfway across the world, that agreement between Russia and Britain drew a line between their interests in the northwest of North America.

It set 54° 40’ north as the southern limit of Russian America’s panhandle.

(The treaty later gave rise to former President James K. Polk’s campaign slogan, “Fifty-four forty or fight!” but

that’s another story).

But because much of the panhandle’s rugged terrain was still unsurveyed, the actual course of the border remained vague.

The Brits imagined a very thin panhandle, the Russians a very fat one.

When the Americans purchased Alaska from the Russians in 1867, they inherited that simmering conflict — which became serious enough to acquire capital letters: the Alaska Boundary Dispute.

The ABD was settled by international arbitration in 1903.

The panhandle’s current land border is 35 miles (56 km) east of where the ocean touches the coast, somewhere in the middle between both extreme claims.

The Canadians, however, were still unhappy.

If the border had been a bit more in their favor, they would have had direct sea access to the Yukon goldfields.

They blamed the British, who had negotiated the deal on their behalf, but favored better relations with the U.S. over a better deal for Canada.

The arbitration also specified Alaska’s maritime border with Canada.

The so-called A-B Line ran from Cape Muzon — the southernmost point on Dall Island, Alaska’s southernmost island — east toward the mainland.

This left most of the Dixon Entrance on the Canadian side of the line.

But that was not how the Americans saw it.

As far as they were concerned, the A-B Line was relevant for the land border; the sea border ran well south of the line, as per maritime law.

This cuts the Dixon Entrance in two, the north going to the U.S., the south to Canada.

Those are the claims that both governments are still sticking to today.

One of the reasons the matter is so hard to resolve is the area’s Pacific salmon.

Each year, several species squeeze through the narrow Dixon Entrance to return to the rivers of the mainland to spawn.

To catch them, fishermen from each side follow the laws of their own country.

As recently as the 1990s, competition between Canadian and American fishermen in the grey zone boiled over into so-called “salmon wars,” both sides occasionally arresting each others’ crews.

In 1997, things came to a head when Canadian fishermen blockaded an Alaskan ferry, effectively holding its passengers hostage for three days.

Things are less tense now.

There’s even a telephone hotline where crews can report violations of standing agreements.

But the core issue has not been resolved.

As the map shows, the gray area is divided into three contiguous zones on either side of the Canadian claim line.

The triangle-shaped one in the middle is interesting because it is not part of the Canadian claim or the American one.

That means it constitutes an area of negative sovereignty, similar to the Bir Tawil triangle between Egypt and Sudan (see also Strange Maps #

396).

It is unclear whether this area is expressly “ungoverned” or not.

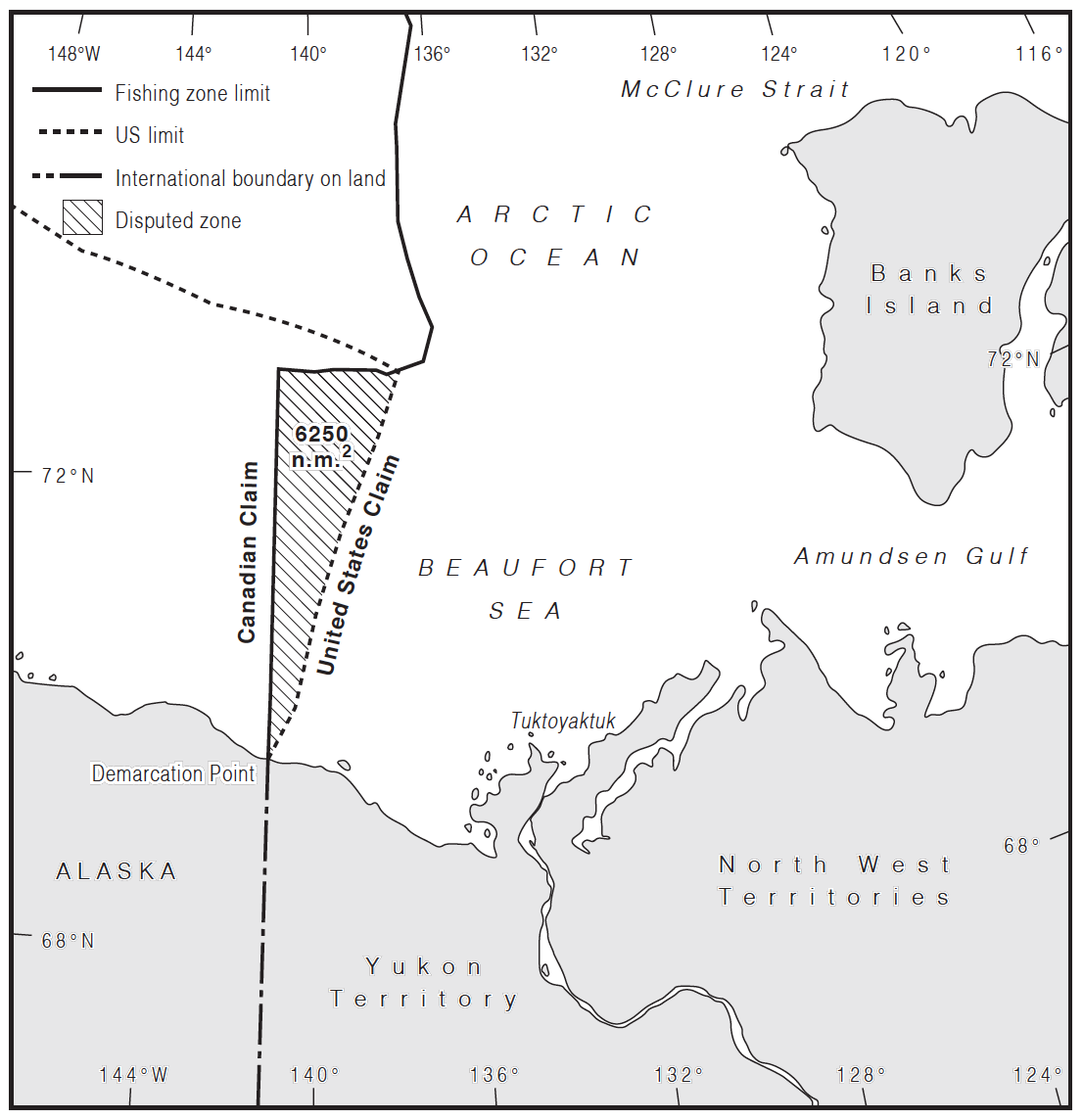

The Beaufort Sea: two bald men fighting over a toupee

The Beaufort Sea wedge measures 6,250 square nautical miles.

Credit: David H.Gray, “Canada’s Unresolved Maritime Borders” (via IBRUat Durham University).

The Beaufort Sea was named after the Royal Navy admiral who invented the scale to measure wind force that also carries his name.

As many geographic features in Canada, it comes with an automatic translation into French: Mer de Beaufort.

That sounds very vacation-y, but do not be fooled.

This is about as cold, windswept, featureless, and uninhabited a part of the world as you may dread to find.

The sea ices over for most of the year, although recently climate change has enlarged the ice-free zone that appears in late summer.

A territorial dispute over a slice of this desolate sea recalls the old saying used by José Luis Borges to describe the Falklands War:

“Two bald men fighting over a comb.”

The dispute is about a wedge-shaped area north of where the border between Alaska and the Yukon territory reaches the sea.

That land border follows the 141st meridian west, as agreed in the 1825 Treaty of St. Petersburg between Russia and Britain.

Fine, proposes Canada: just follow that line 200 nautical miles (230 miles, 370 km) north into the sea, and that is your sea border.

Not so fast, says the U.S., arguing that the marine border should be perpendicular to the coastline as it goes out to sea.

The difference is an area of about 8,100 sq mi (21,000 sq km).

The U.S. and Canada both agree that the sea border should be “equitable,” but they differ on what “equitable” means, in these particular circumstances.

The dispute is inflamed by the important reserves of oil and gas hidden beneath the ice, water, and rock.

According to Canada’s National Energy Board, the wedge could contain as much as 1.7 billion cubic meters of gas and 1 billion cubic meters of oil — enough to satisfy the country’s energy needs many years over.

And in a few years’ time, those reserves could become more accessible, as ice retreats due to climate change.

There is a rather dark irony hiding somewhere in that prospect.

So forget the comb.

A more appropriate simile is not about fighting over something useless, but over something that is improper and outdated.

Like two men fighting over a toupee.

Northwest Passage: as ice recedes, potential for conflict heats up

Some of the route options for the Northwest Passage.

Some of the route options for the Northwest Passage.

Credit: Public domainFunny, here is the Northwest Passage again (see also Strange Maps #

1106).

The search for this drastic shortcut to sea voyages between Europe and East Asia was a motif for many of the earliest European expeditions into North America.

Such a route, through various channels across Canada’s vast northern archipelago, is theoretically possible, if not for the sea ice.

Many expeditions saw their progress blocked by ice or became trapped by it, with the most horrific example being the doomed Franklin Expedition of 1845.

Two ships and 129 men disappeared, their frozen remains discovered more than a century later.

The first to complete a passage this way was the Norwegian Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen, who took three years in the Gjøa, a sloop with a crew of six, to finish the journey in 1906.

In the last few decades, climate change and the resulting decline in sea ice have made Canada’s northern channels more easily navigable.

In 2007, a commercial vessel completed the trip without the assistance of an icebreaker, the first time that has ever happened.

Some of the more navigable channels of the Northwest Passage are very shallow, but there are several other options yet to be fully explored or deiced.

If the northern route could accommodate supertankers and other ships too large for the Panama Canal, it would shave off a big stretch of their only current option: a trip around Cape Horn, on the southern tip of South America.

As global temperatures continue to rise, the Northwest Passage will become increasingly viable for marine traffic, even if only in summer.

That means the territorial dispute over the Northwest Passage is likely to heat up soon as well.

For Canada, the issue is clear and simple: any potential waterway opening up for international shipping will pass through Canadian waters, over which the country exercises full sovereignty, meaning that Canada may grant access or levy tolls as it pleases.

However, the United States and several other countries claim that a viable Northwest Passage would de iure be an international strait, open for transit passage without restriction or compensation, broadly similar to the Bosporus that runs straight through Istanbul (see Strange Maps #

1047).

In 1969, U.S. oil tanker SS Manhattan completed the passage without asking prior permission from the Canadians, and to drive the point home, the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea did the same in 1985.

Even though the latter ship allowed inspection by the Canadian Coast Guard, public opinion in Canada was furious and the trip turned into a diplomatic incident.

In 1986, Canada reaffirmed its sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, a claim the U.S. refused to recognize.

To defuse the situation, both countries in 1988 signed an Arctic Cooperation agreement, which did not touch the sovereignty issue as such, but clarified some practical matters.

Under the Law of the Sea, ships in transit passage do not need permission to pass but may not engage in research while they do.

The agreement proposed that U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy vessels would always be considered to be doing research, so would always need to ask permission to transit.

The treaty held for about a decade.

At the end of 2005, pictures were published of the USS Charlotte at the North Pole.

Canada strongly suspected the submarine had traversed its waters.

It certainly had not asked for permission to do so.

Canada’s tit for America’s tat was that it decided no longer to use the term “Northwest Passage” but designated the area as “Canadian Internal Waters.”

But it was to no avail: the U.S. sticks to its interpretation of international law and reserves the right to treat Canada’s Internal Waters as international waters instead.

Which side will prevail?

At the rate that polar ice is retreating, we will know in a couple of years.

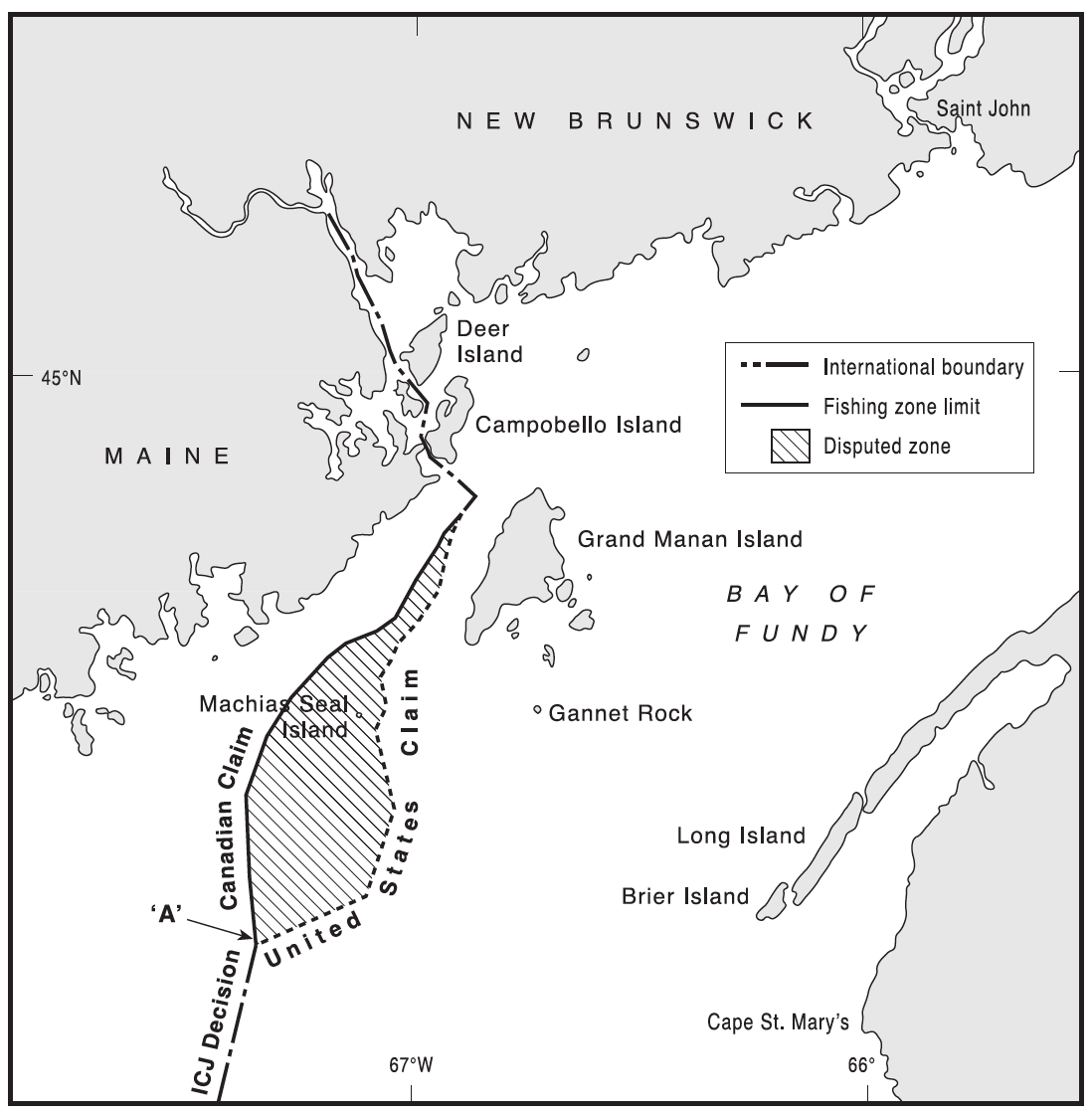

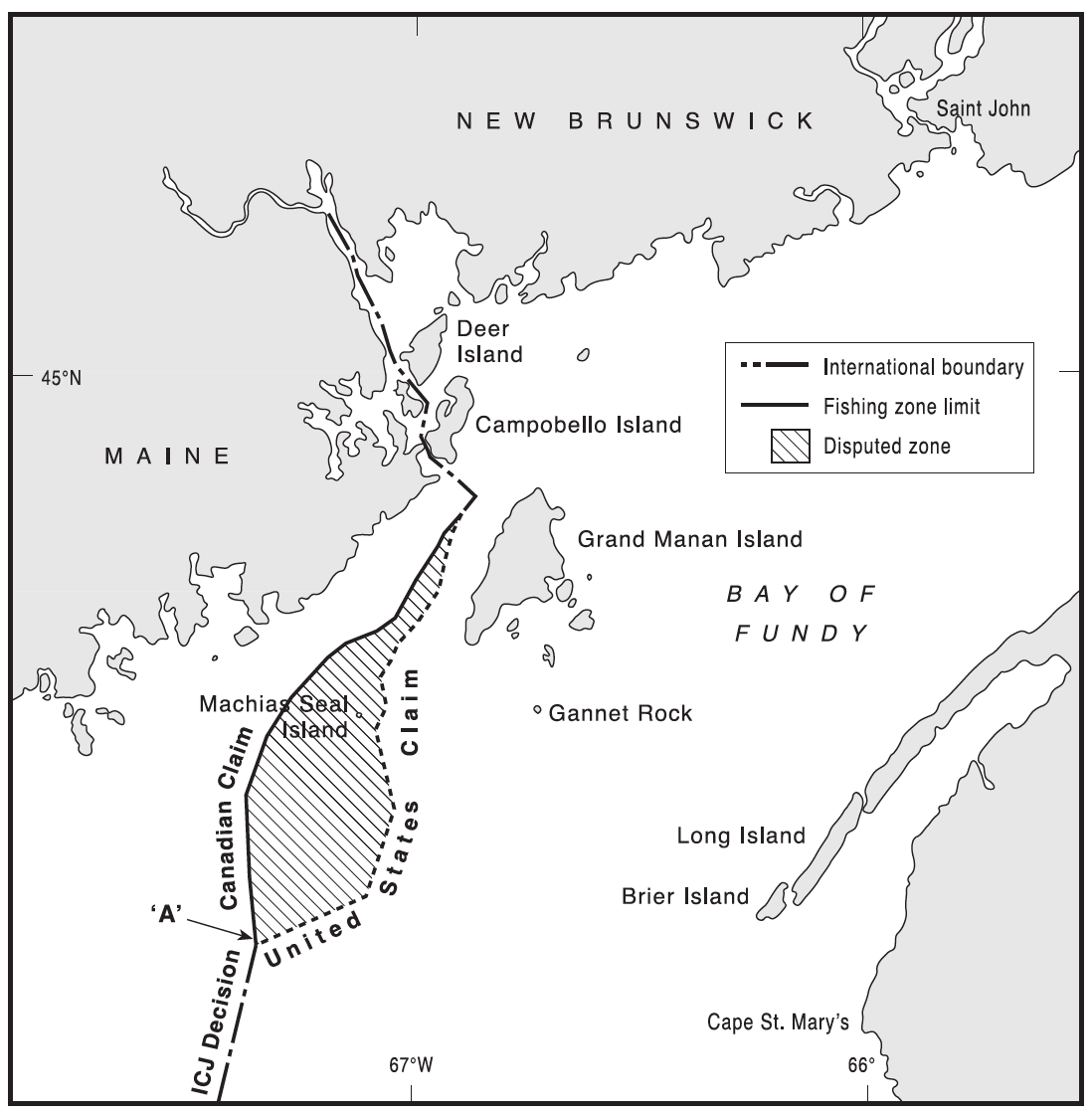

Machias Seal Island: lighthouse keepers without a light to keep

Machias Seal Island is the only actual dry land that is disputed between the U.S.

Machias Seal Island is the only actual dry land that is disputed between the U.S.

and Canada.

Credit: David H.

Gray, “Canada’s Unresolved Maritime Borders” (via IBRUat Durham University).

In 1865, a 7-foot-tall American sailor named Barna Beal landed on Machias Seal Island off the coast of Maine.

Beal, inevitably nicknamed “Tall Barney,” claimed the 20-acre uninhabited island for the United States and single-handedly chased off the British patrol sent to eject him from it.

In his will, he left the island to the first of his descendants to be named Barna.

How much of that is true is debatable.

But in the second half of the 20th century, Barna Norton, Beal’s great-grandson, took up the claim.

He was generous about it though, saying, “The island belongs to me, but everyone is welcome.”

For decades, Norton would bring over groups of tourists to the island on his boat in summer to see the island’s thriving puffin and tern colonies.

Every few years, the Canadian government sent him a cease and desist note, which he duly ignored.

After all, a letter from the U.S.

State Department said he had the right to do so.

Things came to a head every Fourth of July when Norton would parade around the island with an American flag and ask the Canadian lighthouse keepers for rent.

Canada’s counteroffensive would be led by Tony Diamond, a puffin watcher from New Brunswick.

Diamond would stick dozens of small Canadian flags in bird s’ nests around the island.

Norton died in 2004, and it seems there is no new Barna yet to reignite the pantomime war with Canada.

The origins of that war and the geopolitical gray zone that surrounds the island go back to a 1621 land grant that deeded Nova Scotia to a Sir William Alexander.

The Canadians say the grant included the island.

The Americans say the wording is too vague.

That became relevant in 1783 when the British and the Americans signed their divorce papers, a.k.a.

the Treaty of Paris.

Under the generous terms of that treaty, the newly independent U.S.

was granted sovereignty over all islands within 20 leagues (69 miles, 111 km) of its shores, unless they were previously part of Nova Scotia.

Machias Seal Island is fewer than 10 miles off the coast of Maine.

“American,” say the Americans.

But there is that ambiguously worded grant from 1621.

“Canadian,” say the Canadians.

The result was not a Mexican standoff but a Canadian one.

The Canadians had the upper hand but at considerable effort.

Canada sent a steady stream of keepers to the island’s lighthouse, not to operate the light — it had been automated years ago — but solely “for sovereignty reasons.”

In fact, the U.S.

and Canada did have a few other territorial issues in the Gulf of Maine, but those were resolved by the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 1984.

But Machias Seal Island was excluded from that deal.

Both sides seemed willing to let the current standoff continue, as long as its ingredients included nothing more harmful or costly than a steady stream of lighthouse keepers and the occasional barnacle-encrusted local “claimant” to the island.

Meanwhile, tour boats from both the U.S.

and Canada bring birdwatchers to the island.

But Machias Seal Island comes with fishing grounds, which are as disputed as the island, and much more valuable.

In 2002, Canada allowed its lobstermen to fish in the gray zone in summer, bringing them in direct conflict with their colleagues from Maine.

Sometimes, things got physical.

In 2007, a Mainer had his thumb ripped off in the gray zone while jostling with a Canadian for space.

Today, an increasing scarcity of lobsters — a consequence of global warming — is not helping matters.

Some of the route options for the Northwest Passage.

Some of the route options for the Northwest Passage. Machias Seal Island is the only actual dry land that is disputed between the U.S.

Machias Seal Island is the only actual dry land that is disputed between the U.S.

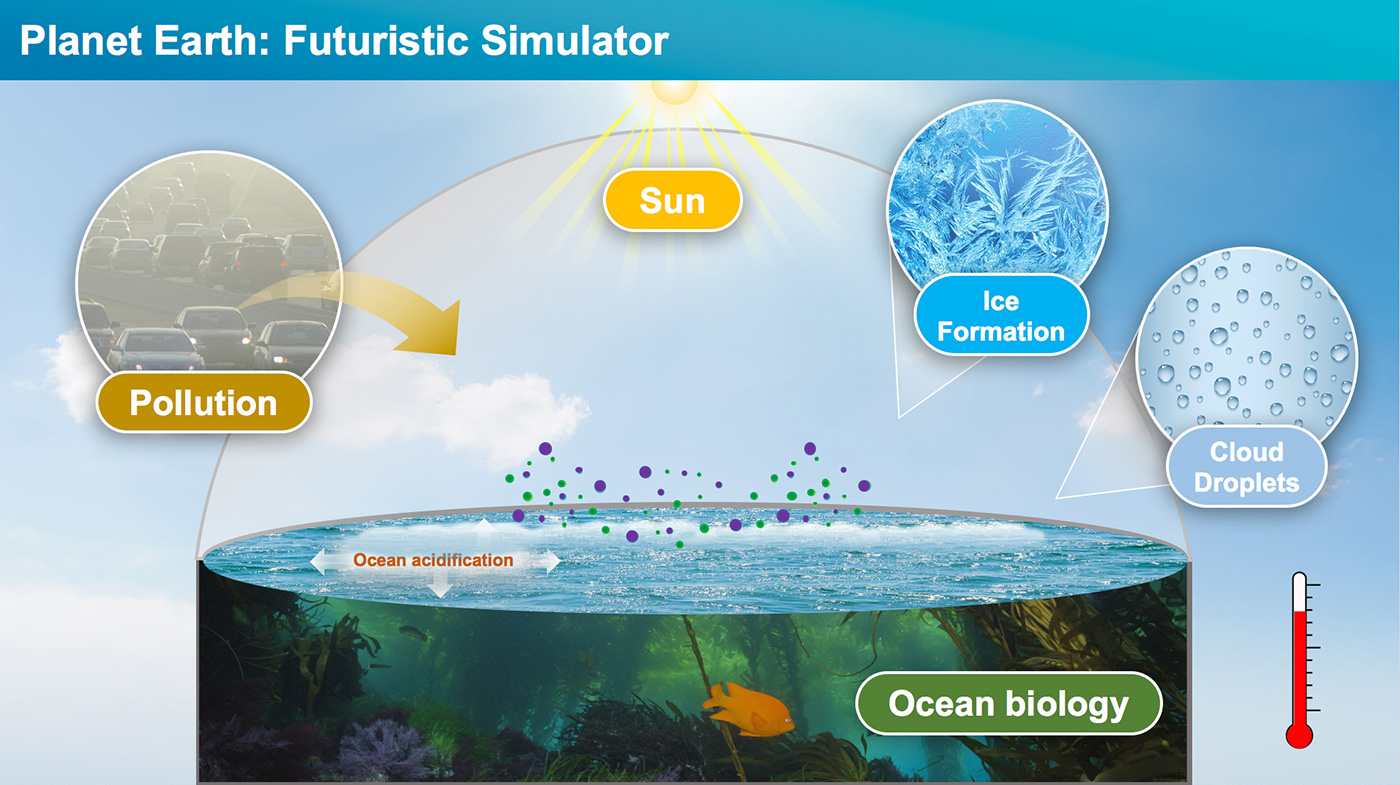

Illustration : SCRIPPS Institution of Oceanography

Illustration : SCRIPPS Institution of Oceanography Illustration : SCRIPPS Institution of Oceanography

Illustration : SCRIPPS Institution of Oceanography