- GeoGarage blog :The Titanic disaster and its aftermath / Titanic: First ever full-sized scans reveal wreck as never ... / A 26-year-old Titanic mystery solved. The discovery leads to new ... / How to escape a sinking ship (like, say, the Titanic) / Explorers can take Titanic's Marconi telegraph, cutting into ... / Titanic sank due to enormous uncontrollable fire, not ... / New images of Titanic wreck revealed / Titanic sinks in real time / New expedition to Titanic site will create 3D map of wreck / First map of entire Titanic wreck site sheds new light on ... / Vow to “virtually raise the Titanic”: new 3-D images taken of ... / Challenge to Titanic sinking theory / Titanic threat: why do ships still hit icebergs? / Her tale will go on: Titanic survivor's story sold at auction

Saturday, July 1, 2023

Titanic: a remembrance

Friday, June 30, 2023

The atlantification of the Arctic Ocean is underway

From Wired by William Von Herff

The discovery of environmental DNA from fish species that have strayed far from their normal range is an ominous reminder of warming, changing seas.

In the Fram Strait off Greenland’s west coast, Véronique Merten encountered the foot soldiers of an invasion.

Merten was studying the region’s biodiversity using environmental DNA, a method that allows scientists to figure out which species are living nearby by sampling the tiny pieces of genetic material they shed, like scales, skin, and poop.

And here, in a stretch of the Arctic Ocean 400 kilometers north of where they’d ever been seen before: capelin.

And they were everywhere.

The small baitfish found in the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans is an ardent colonizer.

Whenever the ocean conditions change, it’s really easy for capelin to expand their range, says Merten, a marine ecologist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany.

It is difficult to estimate an animal’s abundance based solely on the amount of its DNA in the water.

Yet in Merten’s samples, capelin was the most frequently encountered species—far more than typical Arctic fish like Greenland halibut and Arctic skate.

To Merten, the evidence of so many capelin so far north is a bold sign of a worrying Arctic phenomenon: Atlantification.

The Arctic Ocean is warming quickly—the Fram Strait is nearly 2 °C warmer than it was in 1900.

But Atlantification is about more than rising temperatures: it’s a process that is reshaping the physical and chemical conditions of the Arctic Ocean.

Because of the oceans’ global circulation patterns, water routinely flows from the Atlantic into the Arctic.

This exchange mostly occurs in deeper water, with currents carrying warm and relatively salty Atlantic water north.

This warm Atlantic water, however, doesn’t mix well with the Arctic’s surface water, which is relatively cool and fresh.

Fresher water is less dense than saltier water, so the Arctic water tends to float on top, trapping the saltier Atlantic water deep below the ocean’s surface.

As sea ice disappears, however, the surface of the Arctic Ocean is heating up.

The barrier between the layers is degrading and Atlantic water is mixing more easily into the upper layer.

This is kicking off a feedback loop, where warmer surface water melts more sea ice, further exposing the ocean’s surface to sunlight, which heats the water, melts the ice, and allows Atlantic and Arctic water to blend even more.

That’s Atlantification: the transformation of the Arctic Ocean from colder, fresher, and ice-capped to warmer, saltier, and increasingly ice-free.

Merten’s discovery of abundant capelin in the Fram Strait—as well as the DNA she found from other Atlantic species, like tuna and cock-eyed squid, far outside their typical range—is further proof of just how quickly Atlantification is playing out.

And its consequences could be enormous.

In the Barents Sea off Russia, for example, a long-term study presents a grim picture of how Atlantification can disrupt Arctic ecosystems.

As the Barents Sea has grown warmer and saltier, Atlantic species have been “moving in and taking over,” says Maria Fossheim, a fisheries ecologist with the Institute of Marine Research in Norway who led that study.

Fish communities in the Barents Sea, Fossheim says, have shifted north 160 kilometers in just nine years—“three or four times the pace that [previous studies] had foreseen.” By the end of her study, in 2012, Fossheim found that Atlantic species had expanded throughout the Barents Sea, while Arctic species were mostly pushed out.

Merten’s findings suggest the Fram Strait may be heading in a similar direction.

Because this study is the first to examine the diversity of fish in the Fram Strait, however, it is unclear how recent these changes really are.

“We need these baselines,” Merten says.

“It could be that [capelin] already occurred there years ago, but no one ever checked.”

Either way, they’re there now.

The question is: what will show up next?

Thursday, June 29, 2023

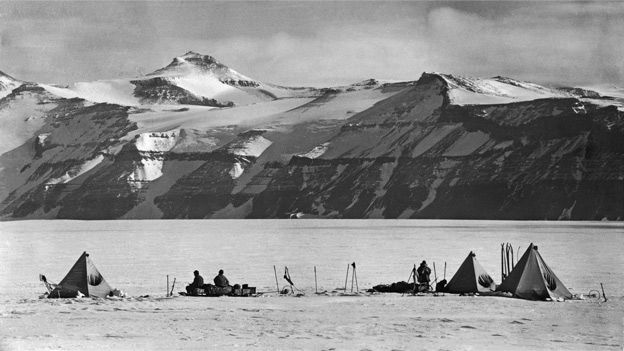

Four things Captain Scott found in Antarctica (and one that found him)

From BBC by Megan Lane

A century ago, Captain Scott and his team set out on a doomed race to be first to the South Pole.

They failed in this quest - but that wasn't all they were doing in this mysterious ice-bound land.

It is an expedition best known for its failure.

Not only did a Norwegian rival beat Captain Robert Scott to the South Pole, but his five-man team died on the return journey.

Found in the tent alongside their frozen bodies were 16kg (35lb) of fossils, a meteorological log, scores of notes, and rolls of film taken by Scott himself.

The dying explorers thought these too valuable to jettison, even though lightening their load could have played a part in the life and death struggle after weeks of travelling in temperatures below -37C (-35F).

Scott's expedition had a dual purpose - to reach the Pole for the British Empire, and to explore and document this great southern land.

This was in answer to a challenge laid down at the International Geographical Congress in 1895, which called the Antarctic "the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken", and one which would result in "additions to knowledge in almost every branch of science".

In the late 19th Century, Antarctica was a large - and largely blank - space on the map.

No-one was even sure if it was a continent or collection of icy islands.

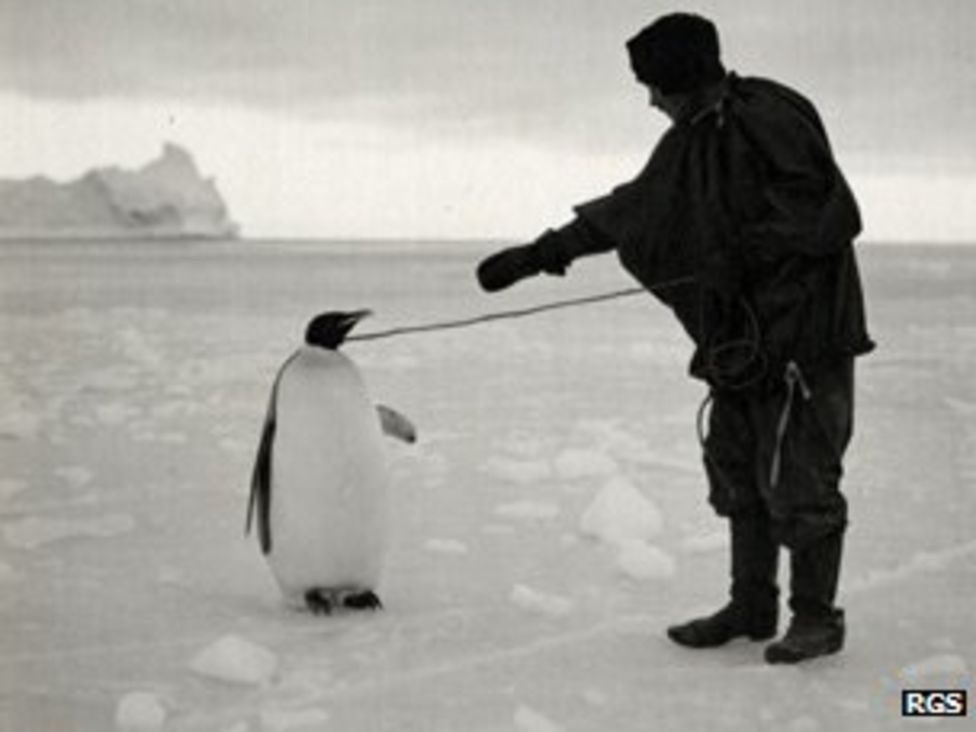

Scott first led an expedition to the region in 1901, and returned a decade later with a young and hungry team of experts - including, for the first time, a professional photographer - to collect a treasure trove of specimens, data and observations for analysis on their return.

Just a handful of his 38-man team set off for the Pole on that final ill-fated journey.

The remainder continued their research around base camp and beyond.

Gathered to answer the pressing questions of their day, these findings continue to shed light on the pressing scientific questions of our day too.

Here are four of their key discoveries (besides the Pole) - and one thing that found them.

Emperor penguin eggs

Of the 2,000 specimens of animals collected by Scott and his team - 400 of which were newly discovered - the jewel in the crown was a trio of Emperor penguin eggs.

At the time, it was thought an embryo passed through all stages of its species' evolution as it developed.

And as the Edwardians assumed the flightless Emperor penguin to be the world's most primitive bird, they hoped the embryos in these eggs would show the link between dinosaurs and birds.

The birds had been seen before, but never with their eggs.

"It was the greatest biological quest of its day," says polar historian David Wilson, whose great-uncle, Edward Wilson, was Scott's naturalist.

"Then they collected the eggs, and all the theories turned out to be wrong."

Penguin skins also collected were used 50 years later as control specimens to prove that the pesticide DDT had since arrived in the seemingly pristine Antarctic.

"The scientific program was so large it basically founded modern polar science," says Wilson.

"So it provides the base line data for almost every study."

Missing link fossil

The prize fossil found alongside Scott's body was the plant Glossopteris indica, an extinct beech-like tree from 250 million years ago.

On the return journey from the South Pole, they stopped to explore a moraine under Mount Buckley (pictured top of this page).

This was no random detour.

Running low on food and struggling against foul weather, the explorer-scientists had a specific goal in mind.

A newly-minted theory held that Antarctica had once been part of an ancient super-continent named Gondwanaland (now Gondwana), and had once had a climate mild enough to support trees.

It was a compelling theory.

All it needed was a killer piece of evidence.

So when Scott and co found this fossil, the same as ones found in Australia, Africa and South America, it was like finding a missing piece of the Earth's jigsaw.

It indicated that these countries had all been part of the same prehistoric land mass.

"The finding of that specimen was a seminal moment," says Wilson.

"It helped us change our geological understanding of the planet."

Wildlife in action

As well as specimens, sketches and photographs, the Terra Nova returned with never-before-seen footage of polar creatures in action.

It was the first time a film camera had been used to make breakthroughs in the study of biology.

It also set the standard for future expeditions and wildlife documentaries.

"Scott believed the camera could play a part in scientific exploration which it hadn't yet achieved," says Wilson, author of The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott.

Expedition photographer Herbert Ponting captured the forms and textures of ice, and filmed the life cycles and behaviours of the region's little-known inhabitants.

In filming Weddell seals chewing holes in the ice with their canine-like teeth, for example, Ponting disproved existing theories as to how the seals created breathing holes.

And, when filming killer whales hunting in a pack, Ponting almost became their lunch.

The ice beneath him heaved and started to split as the whales launched a coordinated attack to spill him into the sea - a behaviour known as wave washing, and recently filmed for the BBC's Frozen Planet.

Rare weather system

At a time of year when temperatures are a relatively balmy -28C, Captain Scott's five-man polar team perished during an extended cold snap when the mercury plummeted to -40C.

The detailed forecast drawn up by meteorologist Dr George C Simpson for the push to the Pole showed no sign of this unfortunate weather event.

In a last message to the British public, Scott wrote: "No-one in the world would have expected the temperatures and surfaces which we have encountered at this time of the year.

It is clear that these circumstances come on very suddenly, and our wreck is certainly due to this sudden advent of severe weather."

An unexpected and rare misfortune, or was the forecast simply wrong?

The former, says Susan Solomon, an expert in atmospheric science and author of The Coldest March.

Simpson's meticulously analysed weather data would have been correct in almost any other year, but 1912 was the one in which the Antarctic winter started hard and early.

His research contributed much to the understanding of not just Antarctica's climate but how upper wind currents interact across the southern hemisphere.

Fungal legacy

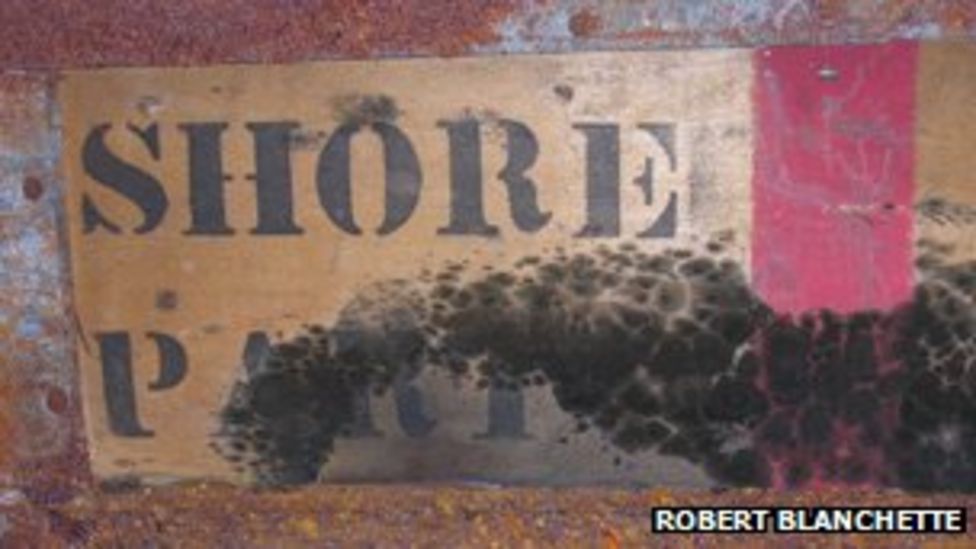

Aptly, Scott's 100-year-old hut is harbouring a new discovery itself.

During restoration work, three new species of wood fungus have been found feasting on the historic hut and its contents.

So the restorers called in plant pathologist Robert Blanchette, of the University of Minnesota, who at first assumed the fungi had hitched a ride with visitors or imported materials.

"But our DNA sequencing, used to identify the fungi, has found that there are species present in the hut wood that have not been previously found and are not similar to known species," says Blanchette.

Further tests have found the same fungi in the Ross Sea region and the Antarctic Peninsula - the opposite side of the continent - and in other historic huts.

Finding new species in Scott's hut is only fitting, says Blanchette.

I am sure these fungi, found 100 years later, would have been of great interest to the biologists and other scientists on Scott's last voyage."

Links :

Wednesday, June 28, 2023

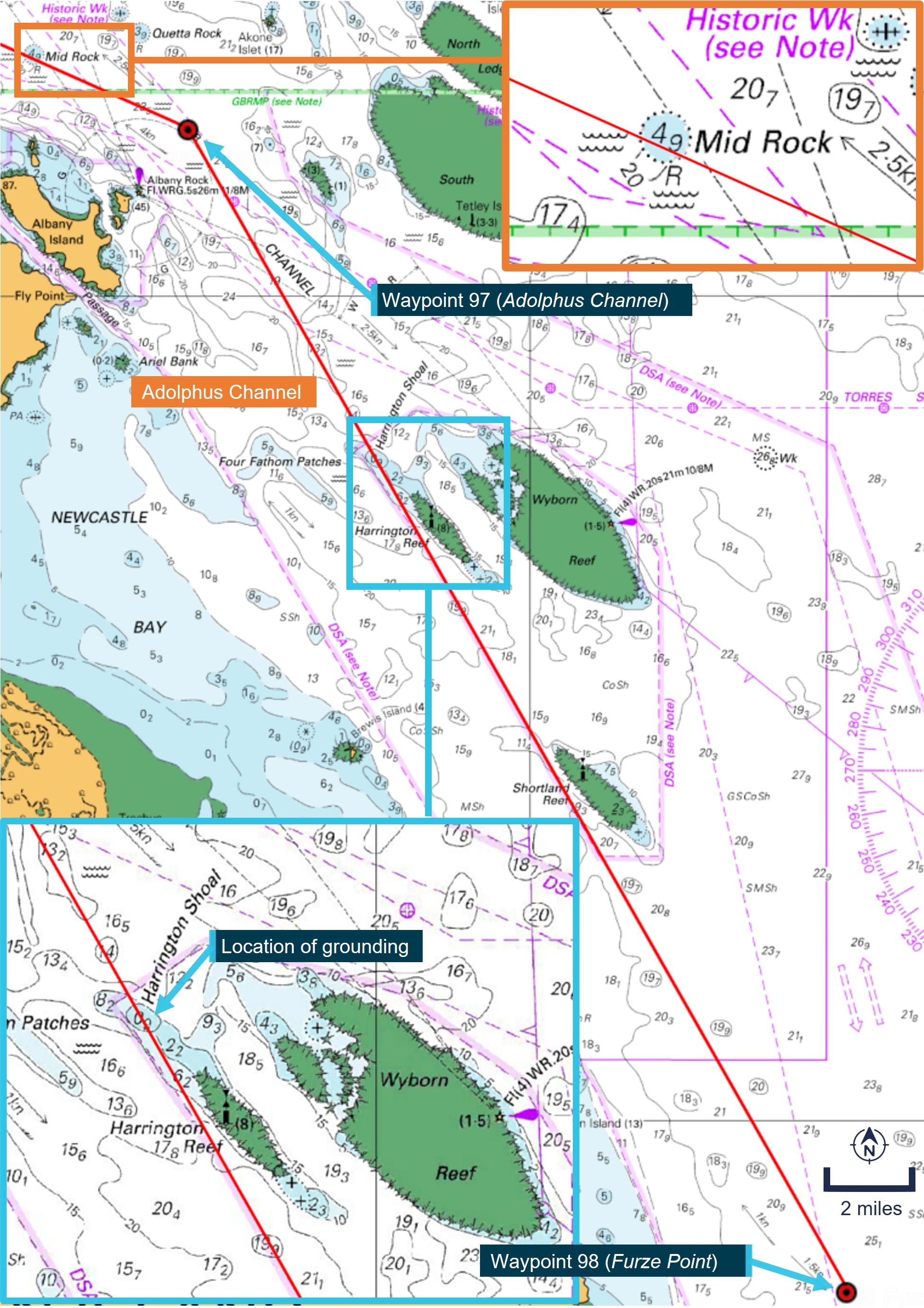

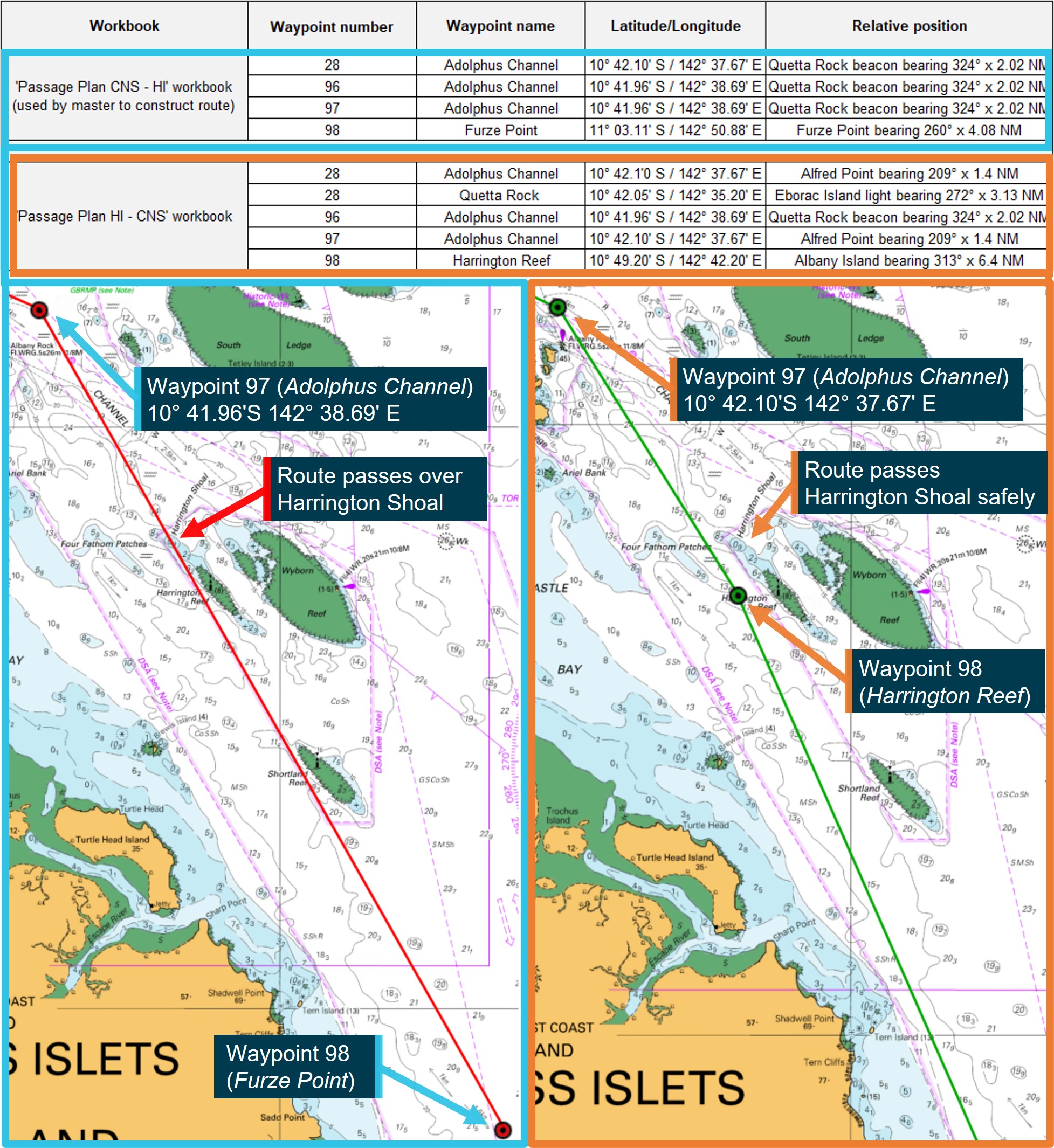

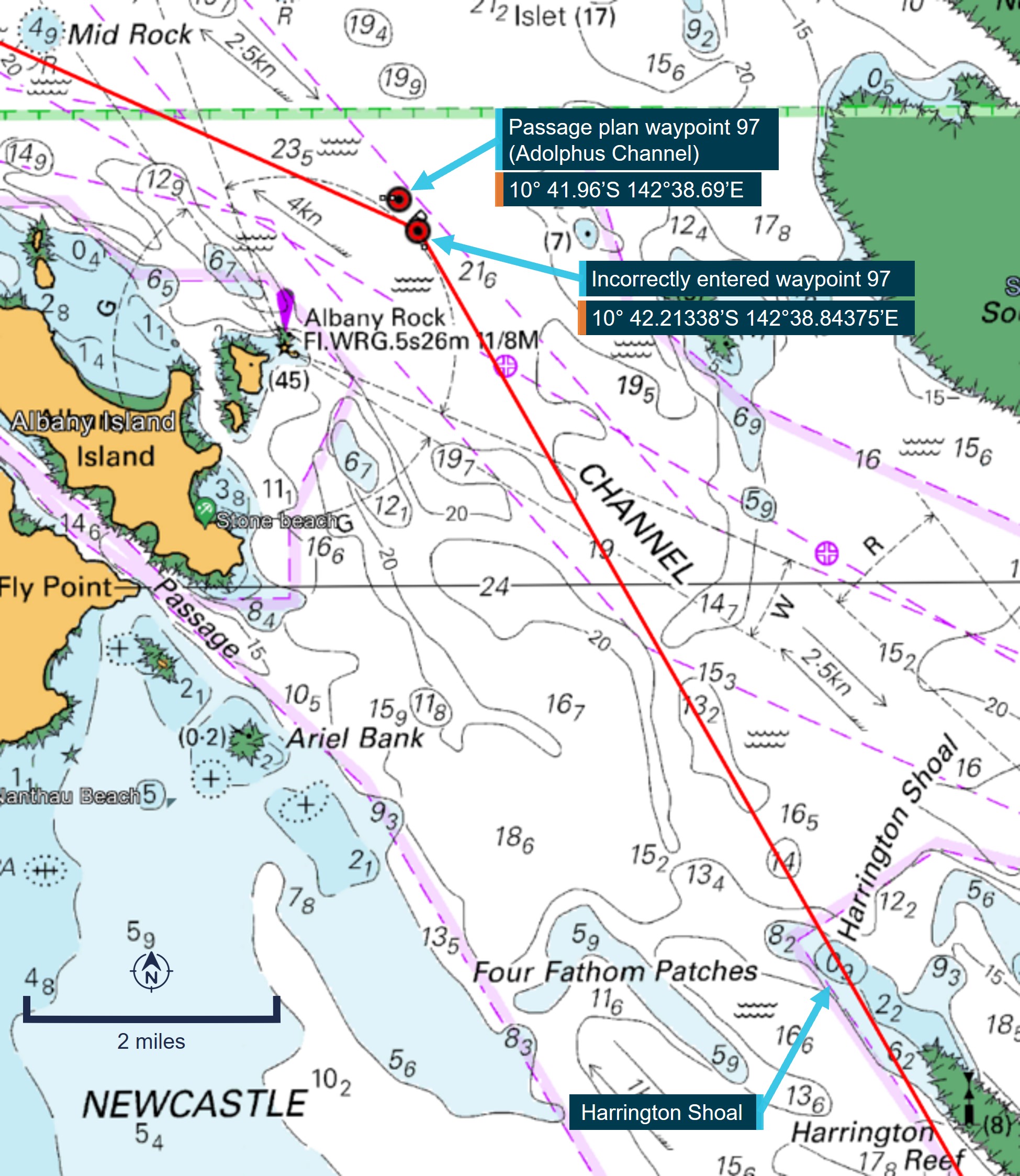

Faulty data and reliance on ECS result in cargo ship’s grounding

From Maritime Excecutive

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau issued a report on a 2021 grounding that it is another example of crews being too dependent on their electronic navigation tools and failing to properly review the information.

While the local cargo ship only suffered hull dents and scrapped paint in the incident, the ATSB faults the crew for failing to verify the route plan, and even when they observed that they were closer to waypoints did not correct the route before the grounding incident.

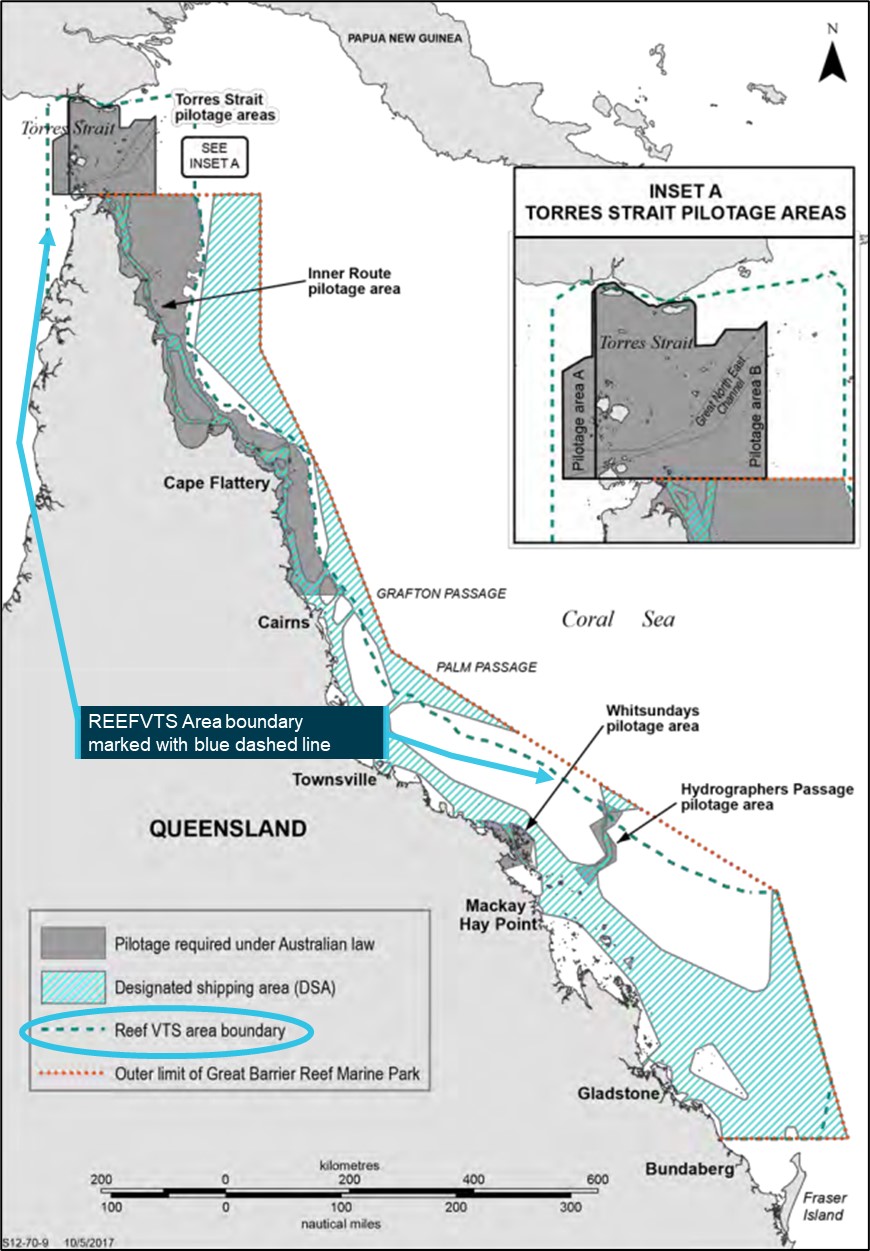

The grounding also highlighted problems with Australia’s monitoring system designed to protect the environment at the Great Barrier Reef.

The Trinity Bay is a 3,150 dwt general cargo ship built in 1996 operated by a crew of nine and managed by Sea Swift of Australia.

The vessel was running a regular route of 520 nautical miles between Cairns in the Far North of Australia and Thursday Island in the Torres Strait.

The ship had been following a standard route over the previous 10 years on its weekly trips between the two ports.

Starting in late 2018 the vessel had received an exemption from the requirement to carry a licensed coastal pilot.

During a voyage prior to the grounding, the master directed the ship’s watchkeeping officers to evaluate the newly created route plan and they did not identify any significant concerns.

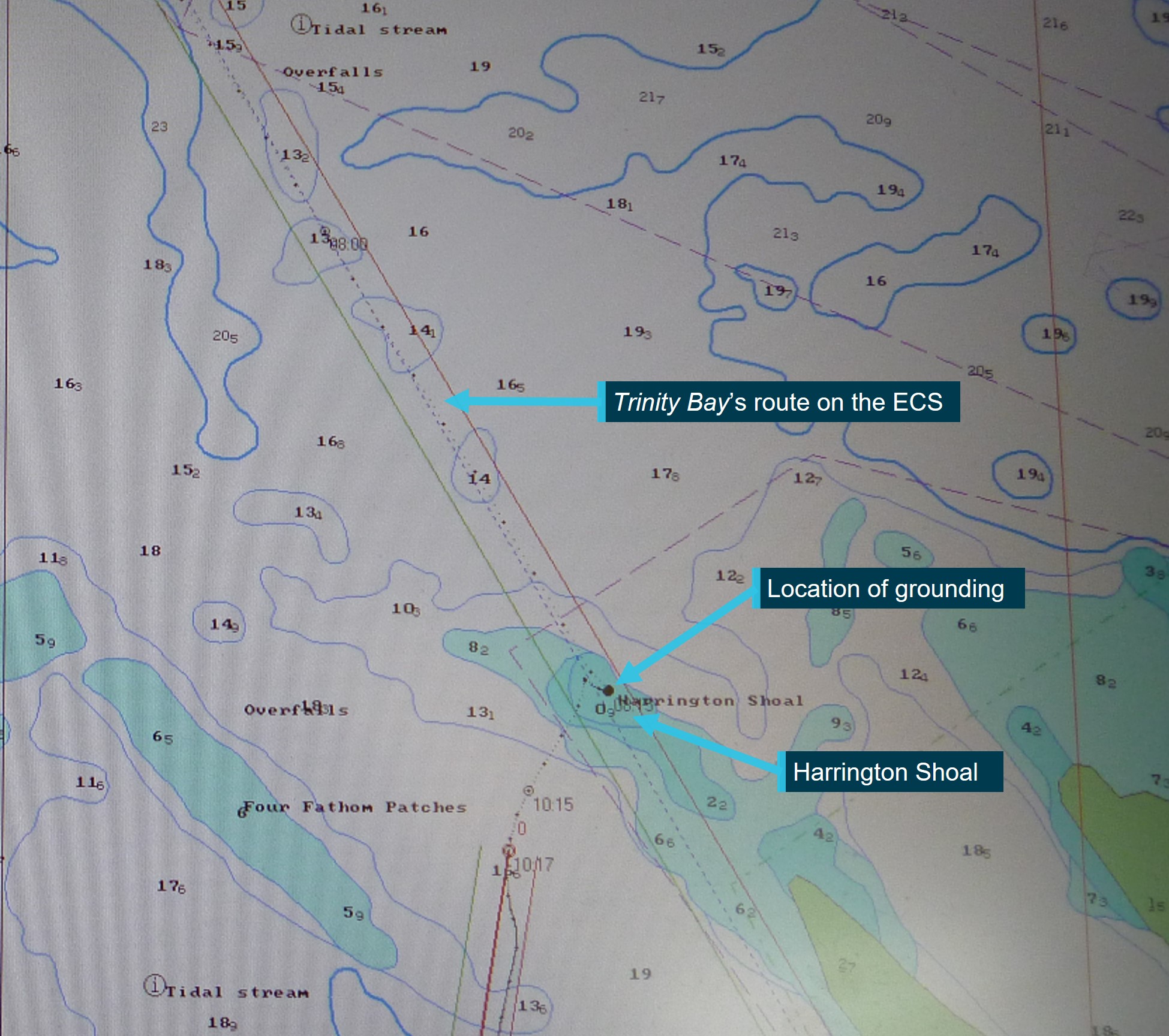

The new routes from the planning tool were then entered into the Trinity Bay’s electronic chart system (ECS), a navigation information system that displayed the vessel’s position and relevant nautical chart data.

However, according to the ATSB the ECS was not approved for use as the ship’s primary means of navigation and did not possess automatic route safety checking functions.

Source: Sea Swift, annotated by the ATSB.

The following morning the chief mate was the officer of the watch with the vessel on autopilot and traveling at about 12 knots.

Shortly after 0730 and following a course alteration, they noted that the parallel index for the radar listed in the voyage plan was incorrect and did not correspond to the planned route.

They however continued to follow the route on the ECS.

About 15 minutes later they also observed that they were closer to the waypoint for Harrington Reef than they were accustomed to but proceeded.

At 0800 a check determined that there was “no cause for concern” on the route but 10 minutes later the bow began to swing sharply to port and the speed plunged.

They began to deballast and less than two hours later on the rising tide, they were able to free the ship and back off the shoal.

A survey showed dents and paint loss but there was no breach or pollution.

The following day after the master was relieved and the ECS was taken out of service, they were able to proceed to Cairns where they arrived on January 22.

The incorrect data in the planning tool had set a course close to the danger of Mid Rock and then directly over the charted danger of Harrington Shoal.

On the day of the grounding, the officer of the watch was primarily monitoring the ship’s passage using the ECS.

While they were marking radar plots on the paper chart, that chart still had the original route marked and they were not using the most appropriate scale for the area.

“This investigation highlights how the development and use of a detailed passage plan in accordance with the accepted principles of passage planning remains essential to safe navigation,” commented Stuart Macleod, ATSB Director Transport Safety.

“Passage planning should be thoroughly appraised, with the route laid out and independently checked on the ship’s primary means of navigation, and then effectively monitored.”

Alarms were received indicating that the Trinity Bay was sailing close to Mid Rock, and again as it approached Harrington Shoal.

The duty operator for the system designed to warn of potential dangers was being presented with an abnormally high number of erroneous alerts and alarms due to the fault and as such acknowledged the alerts but did not follow up on them.

ATSB reports the ship’s operator, Sea Swift, removed the system from service and implemented a mentoring and audit program to ensure crews were following requirements on passage planning and navigation.

Updates were also implemented for the software on the monitoring system and the Great Barrier Reef monitoring was split into two zones after this incident.

In the final report, ATSB highlights the need to confirm and not solely depend on electronic systems.

ATSB says flag administrators and safety investigators have investigated several other groundings identifying common recurring themes related to passage planning and monitoring.

The report cites three additional examples from the UK’s MAIB.

This month the U.S.’s National Transportation Safety Board reported a similar instance where the officers of a cruise ship were depending on an electronic system which turned out not to have up-to-date information resulting in a docking accident causing $2 million in damages.

- MarineLink : Voyage Planning Tool Errors Contributed to Grounding

Tuesday, June 27, 2023

‘A symbol of what humans shouldn’t be doing’: the new world of octopus farming

Can it be done ethically?

The sterile boardroom, much of it taken up by a lengthy white table, is at the heart of the sprawling building in northern Spain.

The corporate chatter that fills this room these days, however, is dominated by the scene playing out one floor below, where about 50 adult male octopuses are in a tank the size of a budget hotel room.

A handful of the octopuses – the fifth generation to be born in this Spanish multinational’s concrete-and-glass office and research centre – skim through the shallow waters, some brushing up against each other while others tuck into the tank’s barren corners.

A low-intensity light casts a pale glow as researchers lay the groundwork for one of the world’s most controversial endeavours: the first commercial octopus farm.

“From a scientific point of view, this project is a global milestone,” says Roberto Romero Pérez, a marine biologist who oversees aquaculture at Grupo Nueva Pescanova.

“The truth is that we’re finding the mood to be a bit more hostile than expected.”

The company’s vision for a farm that could eventually provide up to 3,000 tons of octopus meat a year – requiring the slaughter of about 1 million Octopus vulgaris – came into public view in 2021 when it applied for permits.

The planned farm has since become an international flashpoint, pitting the company and other proponents of octopus farming against those who argue that the solitary, intelligent animals are ill-suited to being farmed.

From Mumbai to Mexico City, protesters have mobilised, adding their voice to the more than 100 academics who contend that farming a carnivorous animal known to be curious, affectionate and exploratory would be unethical and environmentally unsustainable.

Others have sought to crackdown on the sector before it gets started; lawmakers in the US state of Washington are mulling a ban on octopus farming while an online petition calling for a global ban has received nearly 1m signatures.

At the heart of the debate is the question of whether octopuses should be subject to the long-documented mistakes seen in the factory farming of animals such as pigs, says Jennifer Jacquet, a visiting professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami.

Photograph: Brais Lorenzo/EPA

“We’re not having the conversation of should we eat octopus or not, we’re simply at a crossroads where we can decide whether or not to put octopus into mass production.

Do we need to do this? It’s really a luxury good.

It’s not for survival,” says Jacquet.

“This is a symbol of what humans should not be doing in the 21st century.”

Long consumed across the Mediterranean and parts of Asia, as well as Mexico, octopus meat has been growing in popularity globally, as the world’s wealthiest populations embrace octopus-laden sushi, poke and tapas.

Much of the demand has so far been met by wild stocks: between 1950 and 2015 the catch of wild octopuses increased more than tenfold to an estimated 400,000 tons.

While proponents of octopus farming argue that it could help alleviate pressure on wild stocks, there’s little precedent to suggest this will happen, says Jacquet.

A 2019 study that delved into more than four decades of data from around the world suggested that, overall, increases in aquaculture did not result in fewer wild fish being caught.

Instead, researchers found that aquaculture may be contributing to increased demand for seafood.

The decades-long push to farm octopus has played out in parallel with a growing interest in octopus research, offering a deeper understanding of an animal once described as “probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien”.

I’ve never encountered a facility that groups octopuses together without incidents of aggression or escapeAlex Schnell, comparative psychologist

The octopus has long been celebrated for its inquisitive nature, penchant for daring escapes and ability to transform the colour and texture of its skin to mimic its surroundings.

A recent report by the London School of Economics found “very strong evidence of sentience” in octopods.

The finding – which suggests octopuses are capable of experiencing pain and distress – was based on a review of more than 300 scientific studies, including one that found injured octopuses protect a wound by wrapping an arm around it and another that suggested that injured octopuses, if given the opportunity, will self-medicate by seeking out pain relievers.

“Just because an animal has been deemed sentient, doesn’t mean we can’t farm them,” says Alex Schnell, a comparative psychologist who was part of the review.

“But there are certain practices that need to be put in place to be able to farm a sentient animal.”

Currently, there are no EU rules that protect farmed octopuses, as the existing animal welfare legislation doesn’t apply to invertebrates.

The kinds of protections that would be needed to farm octopus – a soft-bodied animal that can be easily hurt by tank collisions or if handled roughly and that requires a mentally stimulating environment – led Schnell and the other members of the research team to conclude that “high-welfare octopus farming is impossible”.

Photograph: Nueva Pescanova

When placed in close quarters, octopus can become aggressive or territorial, says Schnell.

“In my 15 years of experience, I’ve never encountered a facility that groups octopuses together without incidents of aggression or escape,” she says.

“Cannibalism commonly occurs when octopuses are housed together.

Stress from overcrowding or non-ideal living conditions can lead toself-cannibalism, where they eat their own arms.”

Inside a secured area at Grupo Nueva Pescanova’s research facility in Galicia, nine tanks filled with dozens of Octopus vulgaris, the common octopus, sit side by side.

About 15 biologists spend their days here, testing how slight variations in light levels, nutrition and other conditions affect them.

Researchers lift the thick, black plastic curtains that shroud three of the tanks, offering a glimpse into a darkened space containing about 40 spawning females and another tank that is home to a handful of elderly octopuses who researchers suspect are dying.

What the company is keen to show me, however, is the 16 sq metre tank where 50 or so adult octopuses, many of them weighing as much as 3kg, are grouped together.

“We’re not observing any territoriality, or cannibalism, or attacks, or anything like this.

Why? Because the conditions are just right,” says Romero Pérez, citing parameters from water temperature to the lack of predators and ready availability of food.

“So our animals, which is a bit of what most people don’t understand, are in very good condition.

They are in a situation that nobody has seen them in before.

Nobody.”

For this age group, the aim is to gradually increase the size of the tank – the current water depth is slightly less than one metre – and number of animals, says Romero Pérez.

“The aim is to increase the density in order to make it economically profitable.”

While reports suggest that the density could eventually climb to between 10 and 15 animals per cubic metre, he says the exact figure is still being worked out.

“We say that the density will be optimal for the animal to be well,” he says.

“We don’t know what density we can get to.

We’re starting low, then we’ll see how we manage it.”

Romero Pérez describes the project as being in an “experimentation” phase, as researchers gather data that will guide the plans for the farm.

The company eventually envisions a facility where the animals would be divided into about 1,000 tanks based on life phases, with the conditions tailored to promote growth in each phase.

“It’s not the density that is important, but rather the conditions,” says Romero Pérez, who denies the allegations that the animals would at times be subject to constant light.

“It won’t be 24 hours,” he says.

“Different ages have different light requirements, in terms of daylight hours, light intensity and wavelengths.”

Pablo García, one of the centre’s octopus researchers, points to the facility’s tanks, which bear more resemblance to a children’s pool shrouded in black plastic than the fortified glass structures of aquariums.

“Other researchers have told us that if this were their animals, they would have octopuses trying to climb out in the corner, turning up in the hallways or dead out of the water.

But here there’s no problems,” he says.

“For them this would already be cannibalistic fodder, they’re almost afraid to group two or three octopuses together.”

The difference, he suggests, is that these are not wild octopus but rather the fifth generation bred in captivity at the centre.

“There’s been an indirect selection process here,” he says.

“That wasn’t the goal, but in the end you end up with the ones that are best suited to the conditions … The first generation had a different type of behaviour but this has evolved very positively.”

Save for a few large tubes for egg deposits in the females’ tank, the spaces are void of any kind of cognitive stimulus.

“At the beginning we had nooks and crannies, parts of tubes or rocks for them because we were going with what was known,” says Romero Pérez.

“Little by little we pulled them out as we realised they weren’t needed.

What’s important is the temperatures, the oxygen levels, the PH, the light.”

If they have somehow or another managed to selectively breed calm octopuses, where’s their data?Jennifer Mather, professor, University of Lethbridge

The company’s observation flies in the face of what is known about Octopus vulgaris, argues Jennifer Mather, a professor at University of Lethbridge, in Alberta, Canada, who served as the scientific adviser on the Oscar-winning film My Octopus Teacher. “If they have somehow or another managed to selectively breed calm octopuses, where’s their data?” she asks.

Octopuses’ proclivity for brazen escapes have been well documented: from Inky the octopus’s four-metre dash across an aquarium floor and shimmy down a 50-metre drainpipe in 2016 to the century-old story of the octopus at the Brighton aquarium renowned for sneaking out of his tank in the dead of night to feast on lumpfish.

The animals are said to be ‘really active, really exploratory, really likely to escape’.

Photograph: De Agostini Picture Library/De Agostini/Getty Images

Octopuses are known for having strong personalities with huge differences between individuals, says Mather – and Octopus vulgaris is no exception.

“I found vulgaristo be an up-and-at-’em species.

Really active, really exploratory, really likely to escape,” she says.

“In some ways the most interesting of octopuses.

On the other hand, invariably the least likely to tolerate the kind of crap we’re going to do to them.”

A global cohort of companies has for decades been working to unlock the mystery of how to raise octopus in captivity, hoping to cash in on the ballooning trade of an animal that grows quickly and has a high reproductive rate.

Nueva Pescanova – a pioneer in aquaculture, with shrimp and turbot farms that span a surface area of more than 10,000 football fields – pulled into the lead in 2019 after it announced that it had managed to replicate the life cycle of Octopus vulgaris in captivity.

Two years later it began soliciting licences to build a two-storey farm at the port of Las Palmas in Gran Canaria.

The location of the facility, which will be fed by seawater from a nearby bay, was chosen because of the temperature of the surrounding waters.

The company hopes to have its application approved by the end of this year, paving the way for it to begin the two-year task of constructing the reportedly €65m (£55m) farm.

From there, stocked with octopuses transported from the research facility in northern Spain, it would take about a year and a half for the octopus to reach the adult phase.

The timeline suggests the first batch of product – estimated to initially be between 300 and 500 tons of octopus meat – would probably not hit the market before 2027, says Romero Pérez.

From there, the aim is to gradually ramp up production over the next four years to 3,000 tons of meat annually.

This would mean the slaughter of about 1 million octopuses a year – a projection complicated by the lack of existing international standards on the humane slaughter of them.

The aim is to ramp up production to 3,000 tons of meat annually – meaning the slaughter of 1 million octopuses a year

Nueva Pescanova plans to kill the animals using baths of ice flakes and water that would gradually drop to -3C, says Romero Pérez, describing the method as superior to clubbing the animals over the head, and the many unknowns regarding how to stun octopuses with electricity.

For octopuses caught in the wild, a variety of methods are used to kill them, from clubbing to asphyxiation in a net and slicing their brains.

Ice baths are the “standard method used in global aquaculture,” says Romero Pérez.

“Basically, it sets off a neural response that lowers the ability to feel.

It’s the most respectful, most humane form of sacrifice that we know of today.”

His view contrasts with that of the World Organisation for Animal Health, which in 2019 said that the method has been shown to “result in poor fish welfare”.

A 2014 review carried out in part by the Humane Slaughter Association suggested that while fish often stop moving relatively quickly after being placed in ice or ice slurry, “brain activity indicates the potential for the continuation of consciousness for a substantial period”.

Nueva Pescanova says it is working with researchers at a university in the Canary Islands to explore how to improve the slaughter.

“People are imagining things that don’t exist; you don’t take an animal and throw it out there on the ice,” says Romero Pérez, who has worked in aquaculture for more than two decades.

“European legislation allows for immersion in ice water but there is a protocol that needs to be developed before the animal reaches the phase of immersion in ice so that it suffers as little as possible.

And that is what we are working on.”

Photograph: Vuk Valcic/Alamy

As it stands, the mortality rate before slaughter is projected to be between 10% and 15%.

“Our goal is to keep improving it,” says Romero Pérez.

“But it’s very low for the world of farming.

For the species most commonly cultivated in the Mediterranean, for example, the normal mortality rate is between 15% and 20%.”

He argued that it was in Nueva Pescanova’s best interests to keep the mortality rate as low as possible.

“How we make more money is by ensuring animal welfare.

It’s something that seems contradictory, but really that’s the way it is.”

Eurogroup for Animals slammed the company’s justification of the mortality rates as unacceptable.

“This level is a problem to solve, not to repeat,” says Keri Tietge of the group.

How we make more money is by ensuring animal welfare.

It’s something that seems contradictory, but that’s the way it isRoberto Romero Pérez, Grupo Nueva Pescanova

As the company waits to hear on the permits for the farm, campaigners have seized on the drawn-out timeline, calling on the EU to ban octopus farmingas well as imports of farmed octopus.

“We have a chance to stop this before it starts,” says Tietge.

“It’s a very strong signal to all the industry players that are trying to do the same thing.

If they see all this pushback and regulatory troubles, it makes them think twice.”

In the meantime, campaigners have worked to flag the potential environmental impact of the farm, from the waste runoff that could be created by the mass of octopuses to the wild fish that could be needed to sustain a carnivorous animal that requires as much as three times their weight in feed.

“For carnivorous species, these commercial pellet feeds are made with fishmeal and fish oil ingredients, which of course leads to more fishing in order to catch the wild forage fish that these ingredients are produced from,” says Tietge.

This reliance could also potentially exacerbate food security issues in the regions of the global south that are home to the main industrial fishmeal plants, she adds.

Nueva Pescanova says its feed includes byproducts of already-caught fish and that it is working to replace some of the animal protein with plant-based sources.

When it comes to the risk posed by the farm’s runoff, it says it has provided the regional government of the Canary Islands with detailed plans as to how it would disinfect and filter all of the water leaving the facility.

While the project is still proceeding through the standard administrative process and is waiting on the regional government’s environmental impact assessment, it noted that “to-date the initial project complies with all of the requirements”.

It added: “The project for an octopus farm in Gran Canaria falls within an EU mandate that urges us to develop aquaculture as a fundamental element of the blue economy.”

The company says it has a good handle on the octopuses in its research facility, though Tietge contends it remains to be seen how the situation will play out if it attempts to house together more than a million conflict-prone animals known for their ability to take things apart and squeeze through openings the size of a coin.

“I think it is easier not to see these types of problems in the lab setting where there are people constantly tending to the situation and the environment and making sure the conditions are perfect,” says Tietge.

“When you then have nearly 1,000 tanks in production, there’s just no way to control it as much.

So I think they will have a lot of these health and welfare issues popping up in much bigger numbers if they are able to start farming.”

Ultimately, the debate over octopus farming comes down to whether we are prepared to subject octopuses to the same kinds of mistakes we’ve made when it comes to the intensive farming of animals such as pigs, says Elena Lara of Compassion in World Farming.

“We have put very intelligent animals in intensive farms that are now suffering.

Let’s not do it again,” she says.

“Now that we have better science, better knowledge, let’s take that information and use it in the right way. We should learn from the past.”

Monday, June 26, 2023

History Mystery: Who were the light keepers for the old East Pass entrance?

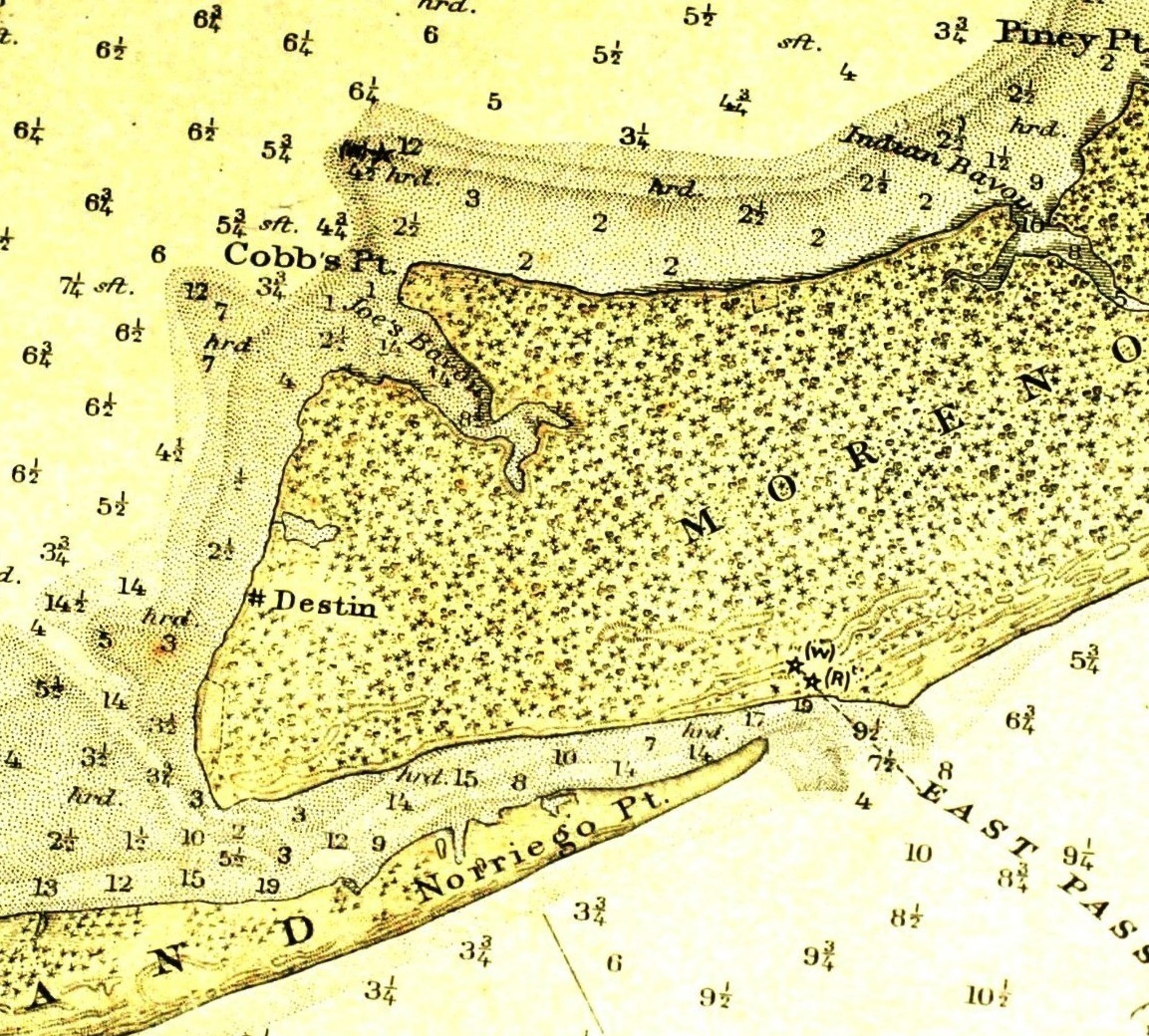

The 1916 nautical chart shows Norriego Point at the end of Santa Rosa Island to the lower left on the chart.

The range lights stood six feet above the mean high-water line.

Actually, the lights were mounted at the top of range dayboards.

Range dayboards/lights are built on land, one behind the other.

Range lights had to be maintained and lighted, then relighted when the kerosene ran out.

The Office of the Lighthouse Engineer in Mobile, Alabama, issued a contract to build and erect the range lights at East Pass to J. H. Gardner of Dalton, Georgia, on Oct. 12, 1897.

The contract called for the work to be completed within four months after acceptance of the contract.

According to the publication Keepers of Florida Lighthouses 1820-1939 by Neil E. Hurley, the first light keeper of the Choctawhatchee East Pass Range Beacons was Clairmon (Clement) Brooks, who was the light keeper until August 1901.

On Aug. 12, 1901, Alfred Destue (Destin) was hired by the Light House Board as the light keeper.

He worked until June 23, 1902, and earned an income of $350 a year.

Alfred Destin was the youngest son of Leonard and Martha Destin, the founders of the fishing village of Destin.

Upon Alfred Destin’s departure in 1902 William T. Marler took over as the light keeper at a salary of $350 a year.

Marler continued as light keeper until September 1910.James W. Ward took over as light keeper on Sept. 1, 1910, at a salary of $450 a year.

There is no record of any other light keeper.

The new East Pass was cut through Norriego Point in March 1929, and after that, there was no need to continue to use the old East Pass.

So, there was no longer a need for the range lights or the light keepers.

Sunday, June 25, 2023

Orca encounteer at Gilbraltar for Team Jajo

"This was a scary moment," Team JAJO skipper Jelmer van Beek said.

"Three orcas came straight at us and started hitting the rudders. Impressive to see the orcas, beautiful animals, but also a dangerous moment for us as a team.

"We took down the sails and slowed down the boat as quickly as possible and luckily after a few attacks they went away."

The Mirpuri/Trifork Racing team of Portugal also reported a run-in with orcas, organisers said, adding that there were no injuries or damage to either boat.

Authorities have noted a steady increase in interactions between orcas and vessels in the Strait of Gibraltar and Portugal, with more than 20 incidents in May alone.

In some cases, boats have been significantly damaged, at least three to the point of sinking, organisers said, and the behaviour appears to be spreading among different killer whale family groups.

Earlier this week, an orca repeatedly rammed into a yacht in the North Sea off Shetland, in the first such incident in northern waters.

- Marine mammal science : Killer whales of the Strait of Gibraltar, an endangered subpopulation showing a disruptive behavior

- WP : Why orcas keep sinking sailing boats ?

- Business Insider : The orca boat attacks are likely to escalate, former SeaWorld trainer says. 'Orcas love having fun, but they can have a darker side.'