From The Conversation by Adam Lockyer

Last week it was

reported an Australian warship had, in early July, been closely followed by a Chinese guided-missile destroyer, a nuclear-powered attack submarine, and multiple military aircraft as it travelled through the East China Sea.

This incident followed a

confrontation on May 26, when an Australian maritime surveillance plane was dangerously intercepted by a Chinese fighter over the South China Sea.

Reportedly, the Chinese fighter flew treacherously close to the Australian plane, releasing flares, before cutting across its path and dropping chaff (a cloud of aluminium fibre used as a decoy against radar).

While there are good reasons not to exaggerate these events, the bad news is these incidents are almost certain to continue.

When they do occur, it’s important to place them within their broader historical and geopolitical context and not sensationalise them – we must not frame them as if we’re on the brink of war.

The good news: 3 reasons not to panic

There are three reasons why the significance of these events shouldn’t be exaggerated.

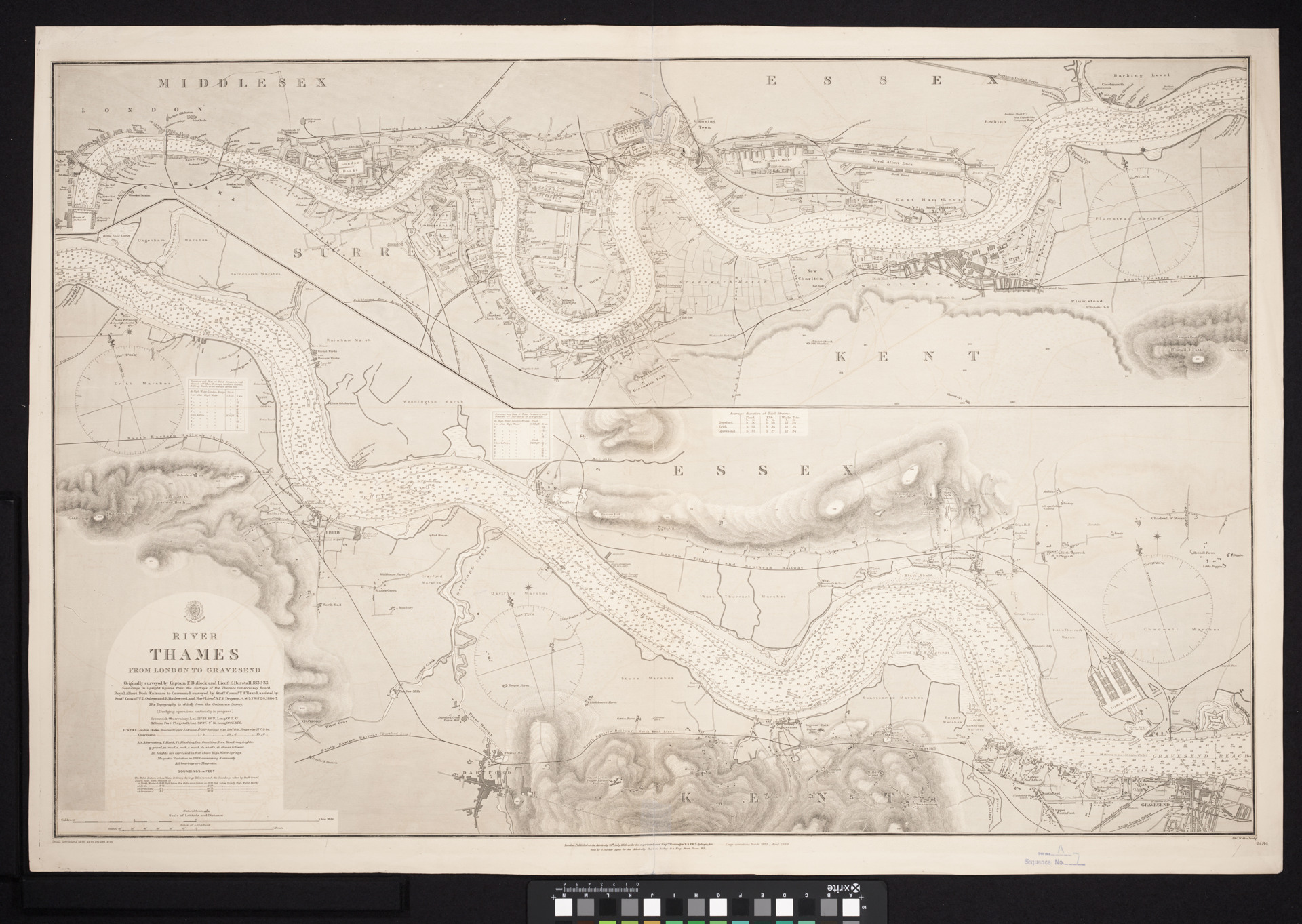

First, Asia’s seas are among the world’s busiest.

The warships of different navies are constantly operating in close proximity with each other and most of these interactions are professional and even courteous.

This includes most encounters with the Chinese navy.

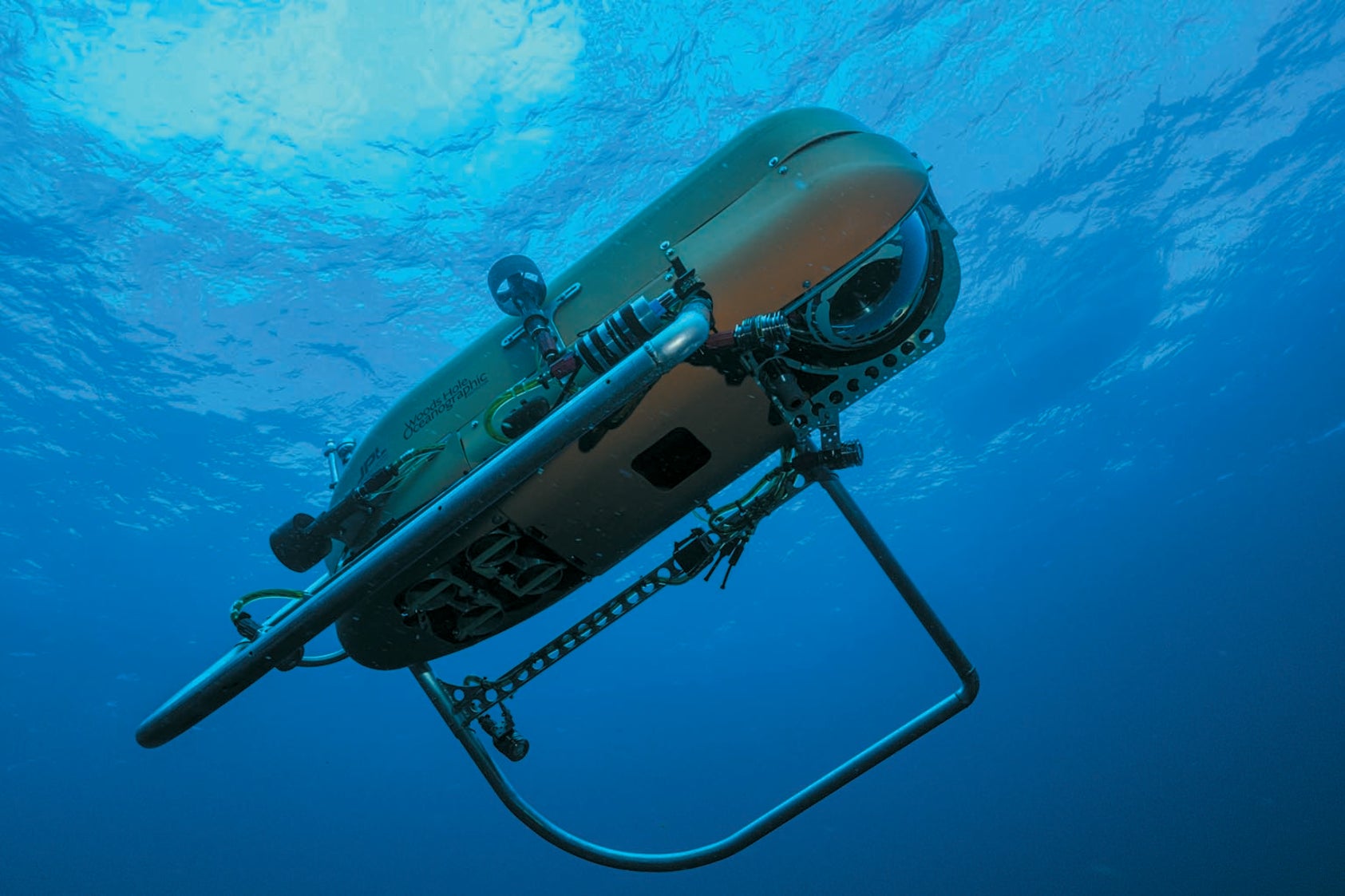

A second, and related, point is that both the Chinese and Australian navies have grown significantly in size over the past decade.

More ships means more total days at sea, which means more opportunities for the navies to come into contact.

Most of these encounters are innocuous.

In our research on

Australia’s naval diplomacy, for instance, the team at Macquarie University investigated

reports a Chinese ship had spied on HMAS Adelaide visiting Fiji.

The reality, however, was the Chinese ship was deployed semi-permanently to the South Pacific as a satellite relay and regularly came in-and-out of Suva (Fiji’s capital) for supplies.

It was nothing more than a chance run-in.

Third, although confrontations aren’t common, they are also far from unprecedented.

During the Cold War, the warships of the United States and the Soviet Union frequently sparred.

Few forward deployments occurred without some contact with the opposing forces that may have included overflights, shadowing or dangerous manoeuvring.

Indeed, potentially dangerous interactions were common enough that in 1972 the Americans and Soviets signed the Incidents at Sea (INCSEA)

agreement.

The agreement spelt out the “rules of the road”.

The superpowers also committed to an annual meeting between their senior naval officers, with the hosting responsibility alternating between them.

The agreement didn’t eliminate incidents at sea, but it did create a mechanism for the two parties to vent their frustrations, voice their protests and work constructively on solutions.

As the meetings were between the two nations’ top professional naval officers, there was a

high degree of mutual respect and a genuine attempt to make the seas a safer place for their sailors.

The bad news: these incidents will continueThe US attempted to replicate their Soviet agreement with China. In 1998, the US and China

agreed to the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement, which copied many of the successful parts of the Soviet agreement, including the annual meeting between their admirals to discuss concerning incidents.

The challenge, however, is that the geopolitical backdrop to the US-China agreement is significantly different from its Cold War antecedent.

During the Cold War, tensions at sea rose and fell just as they did on land.

However, the areas where the Soviet Union attempted to assert its claims (such as the Sea of Okhotsk and the Barents Sea) were isolated and icy and generally unimportant to everyone except the Soviets.

The Americans would prod there occasionally on intelligence gathering, freedom of navigation operations, or simply to rile up their rivals – but on the whole both sides understood the game.

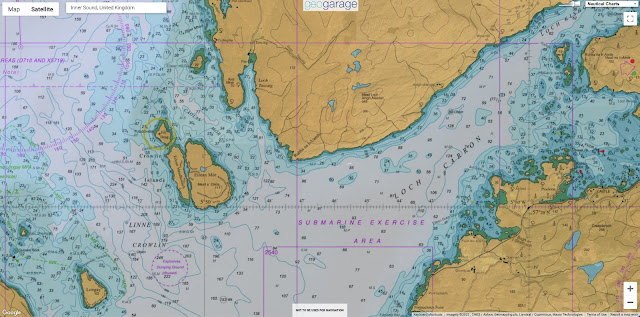

In contrast, China has claimed exclusive coastal territorial sovereignty over the majority of the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait and large parts of the East China Sea.

These are among the most geopolitically important and busiest waterways in the world.

Beijing’s options for convincing regional states to recognise its claims are limited, especially when foreign navies continue to traverse these waters, dismissively ignoring China’s sovereignty declarations.

Beijing has few options

Politically, China could attempt to horse trade, such as we’ll treat you as the custodians of the South Pacific if you accept our claims to the South China Sea.

Or use economic and diplomatic coercion.

In Australia’s case, neither of these strategies are likely to be successful as they would undermine our relationship with the US, and there’s the fear China will renege in the future.

This leaves tactical deterrence.

Describing how deterrence works, American economist Thomas Schelling used the

analogy of two people in a row boat where one starts “rocking the boat” dangerously, threatening to tip it over unless the other one does all the rowing.

The threat is shared equally between them, but the boat rocker is counting on the other to back down because their appetite for risk is lower.

Confrontations in the air and sea are risky for both the perpetrator and the target.

On 1 April 2001, for instance, a Chinese fighter

collided with an American signals intelligence aircraft.

The American plane was forced to make an emergency landing on Hainan Island, while the Chinese plane crashed and the pilot died.

What China is counting on is Australia not being as risk tolerant as they are.

They hope Australia will blink first.

But, Australia has shown no indication it will stop deploying to the region. Indeed, the aircraft that was threatened and damaged by chaff on May 26 was one of two Australian aircraft flying out of the Philippines at the time.

The Australians were not deterred and the second aircraft appears to have flown missions on

May 27, May 30 and June 2 through the same airspace as the incident occurred.

As China and Australia have few other options than to continue doing what they’re doing, these incidents look likely to continue.

When they occur, however, it’s important they’re not taken out of their historical and operational contexts.

Links :

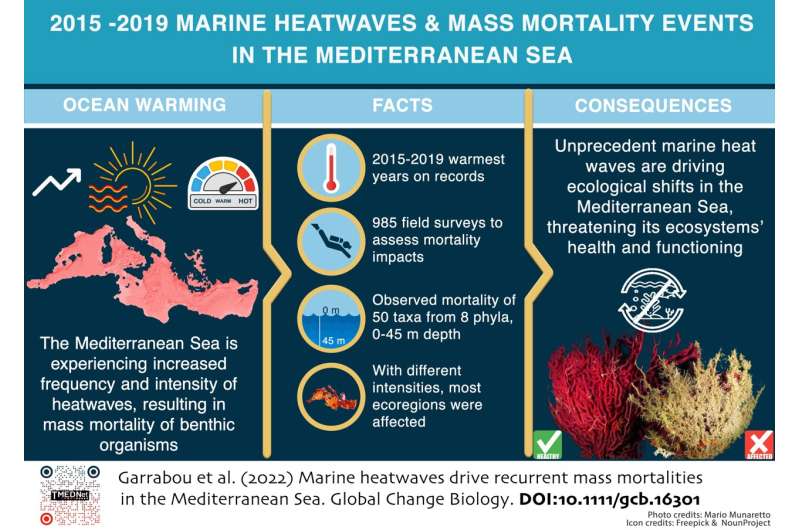

Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea.

Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea.