A powerful interview of Ian Urbina, coupled with visuals from The Outlaw Ocean reporting.

From The Medium

This week we tell of the untold stories of what happens at sea, in the context of a forthcoming book by Pulitzer Prize winning investigative journalist, Ian Urbina.

Titled “The Outlaw Ocean”, this compelling new book profiles the most urgent ocean issues facing us today: illegal fishing, human and arms trafficking, slavery at sea, illegal dumping, piracy, and more.

Titled “The Outlaw Ocean”, this compelling new book profiles the most urgent ocean issues facing us today: illegal fishing, human and arms trafficking, slavery at sea, illegal dumping, piracy, and more.

The Outlaw Ocean is a riveting, adrenaline-fueled journey through some of the most dangerous regions of the earth: the high seas, where lawlessness and physical risk prevail. Ian Urbina — Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The New York Times — gives us a galvanizing account of the several years he spent exploring and investigating the high seas, the industries that make use of it, and the people who make their, often criminal, living on it.

It is a truism to state how little we know about the ocean.

And we take solace in the efforts, increasing every day, to map and study the water column, the ocean floor, the community of marine species, the systems of circulation, weather patterns, and consequence of changing climate conditions.

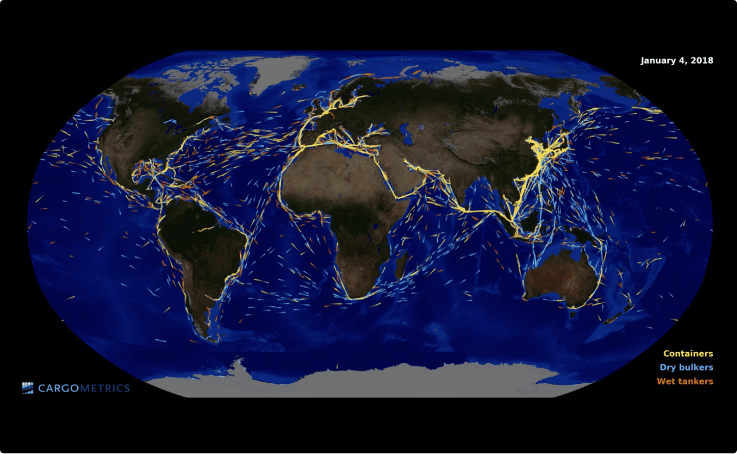

We are aware of the transport and trade aspects of the ocean connection in the distribution of goods, people, and ideas.

We may be aware of the communications and financial exchange utility of underwater cables and other evidence of the overt value of the ocean for so many aspects of our lives.

But what we don’t know is the dark side of the ocean, the social involvement of many faceless people the world over who earn livelihood from the sea, build and install the ships and rigs, man coastwise transport and service vessels, and fish the water along shore and on the high seas far from our sight, outside our mind.

As an observer of the world ocean, I am too aware of the shallow spread of our knowledge and understanding of all these involvements: not just the science or the larger implications of globalization on our community living, but also the monetary intricacies of ship ownership, management companies, the use of national flag registries, manning and recruitment, port clearances, insurance, and the resolution of disputes that often take place outside of normal jurisdictions.

But what frustrates me the most is the untold human stories, the invisibility of the maritime worker and his or her life at sea.

Where do they come from?

Why do they engage in what is surely a most lonely and dangerous way to make a living?

How do they find their way to the sea?

How are they paid and treated aboard?

What happens when things go wrong?

Ian Urbina, a prize-winning investigative reporter at the New York Times, has provided answers to these questions in The Outlaw Ocean, to be published in August by Alfred A. Knopf, as a compelling, informed, sympathetic revelation of a reality in which so many of these workers live, the corruption and criminal indifference, the inhuman physical and psychological conditions, the few safety and legal protections in the face of constant dangers, the physical and sexual abuse, and the violations of contracts, protective regulations and laws, and any basic sense of moral obligation and human rights for any workers anywhere.

It is a sordid, sad, infuriating story told by Urbina with thoroughness, responsibility, narrative grace, sympathy, and insight into what is, and what can or cannot be done to illuminate an unknown problem and to rectify an unacceptable situation that underlies every aspect of the maritime contribution to the well-being of the rest of us worldwide.

The contents cover the extent of the problem: a Greenpeace vessel tracking and challenging an outlaw fishing ship in the Southern Ocean; the futility of enforcement even where good laws exist; the invention of an independent sea-based nation; ships and crews abandoned for unpaid bills; smuggling; insurance fraud, wreck thieves and repo men; poachers and conservationists; conflict between deep ocean engineering and conservation interests; sea-bound abortion providers; slavery and human trafficking; illegal waste disposal; violence between ships at sea; piracy; confrontations with whale hunters; and other examples of brutality, exploitation, and criminality in “a floating world where anyone can do anything because no one is watching.”

Urbina bears witness by putting himself in the midst of all this, not as some distant observer, but as real-time participant in events and places where good sense might argue against his need for a story, “a process,” he writes, “that felt both worthwhile and pointless…feeling like an explanation for its own sake: that single abiding certainty at the core of journalism, that there is merit…in giving voice to those who lacked it.”

He wonders, “if these were legitimate motivations or professional delusions.”

“Still, I clung to the hope that by my putting the information out there, other people might use it somehow to change things.”

Legitimate and powerful journalism, without delusion, is the outcome of The Outlaw Ocean.

That these stories are finally, and brilliantly told, is an essential contribution to what we need to know about the ocean and what we must do to protect and sustain every aspect of its human dimension.

And we take solace in the efforts, increasing every day, to map and study the water column, the ocean floor, the community of marine species, the systems of circulation, weather patterns, and consequence of changing climate conditions.

We are aware of the transport and trade aspects of the ocean connection in the distribution of goods, people, and ideas.

We may be aware of the communications and financial exchange utility of underwater cables and other evidence of the overt value of the ocean for so many aspects of our lives.

But what we don’t know is the dark side of the ocean, the social involvement of many faceless people the world over who earn livelihood from the sea, build and install the ships and rigs, man coastwise transport and service vessels, and fish the water along shore and on the high seas far from our sight, outside our mind.

As an observer of the world ocean, I am too aware of the shallow spread of our knowledge and understanding of all these involvements: not just the science or the larger implications of globalization on our community living, but also the monetary intricacies of ship ownership, management companies, the use of national flag registries, manning and recruitment, port clearances, insurance, and the resolution of disputes that often take place outside of normal jurisdictions.

But what frustrates me the most is the untold human stories, the invisibility of the maritime worker and his or her life at sea.

Where do they come from?

Why do they engage in what is surely a most lonely and dangerous way to make a living?

How do they find their way to the sea?

How are they paid and treated aboard?

What happens when things go wrong?

Ian Urbina, a prize-winning investigative reporter at the New York Times, has provided answers to these questions in The Outlaw Ocean, to be published in August by Alfred A. Knopf, as a compelling, informed, sympathetic revelation of a reality in which so many of these workers live, the corruption and criminal indifference, the inhuman physical and psychological conditions, the few safety and legal protections in the face of constant dangers, the physical and sexual abuse, and the violations of contracts, protective regulations and laws, and any basic sense of moral obligation and human rights for any workers anywhere.

It is a sordid, sad, infuriating story told by Urbina with thoroughness, responsibility, narrative grace, sympathy, and insight into what is, and what can or cannot be done to illuminate an unknown problem and to rectify an unacceptable situation that underlies every aspect of the maritime contribution to the well-being of the rest of us worldwide.

The contents cover the extent of the problem: a Greenpeace vessel tracking and challenging an outlaw fishing ship in the Southern Ocean; the futility of enforcement even where good laws exist; the invention of an independent sea-based nation; ships and crews abandoned for unpaid bills; smuggling; insurance fraud, wreck thieves and repo men; poachers and conservationists; conflict between deep ocean engineering and conservation interests; sea-bound abortion providers; slavery and human trafficking; illegal waste disposal; violence between ships at sea; piracy; confrontations with whale hunters; and other examples of brutality, exploitation, and criminality in “a floating world where anyone can do anything because no one is watching.”

Urbina bears witness by putting himself in the midst of all this, not as some distant observer, but as real-time participant in events and places where good sense might argue against his need for a story, “a process,” he writes, “that felt both worthwhile and pointless…feeling like an explanation for its own sake: that single abiding certainty at the core of journalism, that there is merit…in giving voice to those who lacked it.”

He wonders, “if these were legitimate motivations or professional delusions.”

“Still, I clung to the hope that by my putting the information out there, other people might use it somehow to change things.”

Legitimate and powerful journalism, without delusion, is the outcome of The Outlaw Ocean.

That these stories are finally, and brilliantly told, is an essential contribution to what we need to know about the ocean and what we must do to protect and sustain every aspect of its human dimension.