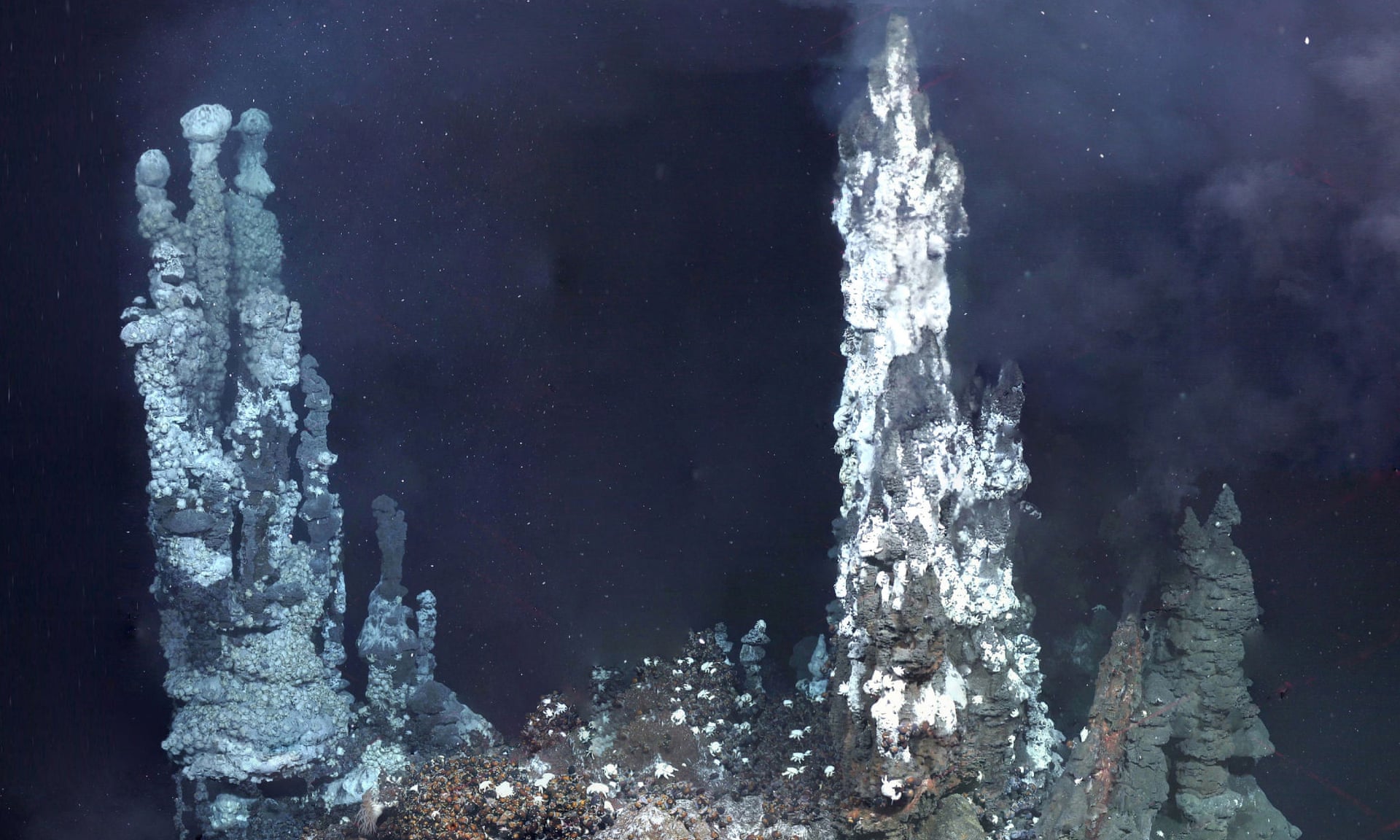

Footage from the deep hydrothermal vents in the Caribbean.

At sites like this, mineral deposits are formed, including gold and zinc.

HROV Nereus Dive 061 at the Von Damm hydrothermal vent field, Mid-Cayman Rise

courtesy of www.schmidtocean.org

From The Guardian by Damian Carrington

Huge rich-metal deposits on the ocean floor could transform the global commodities market but there are fears mining them could harm rare ecosystems

A scientific expedition has been launched from the UK to explore the mining of rich metal deposits on the deep ocean floor, which are the focus of a new gold rush around the world.

The UK research vessel, the RRS James Cook, left Southampton on Thursday, heading for the underwater ridge in the middle of the Atlantic where volcanic activity drives hot springs, also known as black smokers.

“They have left these incredibly metal-rich deposits as mounds on the sea bed, about the size of a big football stadium,” said Bramley Murton, from the UK’s National Oceanography Centre, who is leading the expedition.

“The aim is see whether they are a viable source of essential metals in the future, both in terms of economics and environmental sustainability.”

The metals are vital for many aspects of modern society, from smartphones to aircraft to green energy, but China has a virtual monopoly on many of them.

The scientists leading the expedition, which will deploy a giant metal detector, scanners and drills, says mining the deep sea resources could transform the global market.

Prime minister David Cameron has said such exploits could be worth £40bn to the UK alone and in March, a UK company won a second licence from the International Seabed Authority to prospect in 75,000 sq km of the Pacific.

There are fears that deep sea mining could harm the extraordinary creatures and ecosystems that live on the hot springs that deposit the metals.

But the new voyage will only examine hydrothermal vents that have been extinct for thousands of years and no longer host the unique vent ecosystems.

Formation of mineral rich chimneys on the Atlantic ocean floor, East Scotia Ridge.

Photograph: National Oceanographic Centre

They will use robot submarines to be the first to drill into extinct vent deposits, using a specially hardened drill to probe 55 metres below the sea bed.

They will also deploy a giant metal detector into the dark ocean depths.

“It is hovered over the sea bed at three to four metres and moved very slowly along,” said Murton.

More data will come from two instruments - called Daisy and Sputnik - that use electromagnetic waves to get a 3D image of the deposits, like a medical CT scan.

A key question is how much the seawater has rusted away the metals deposited by the hot springs that stopped flowing up to 50,000 years ago.

The deposits can be extremely rich in valuable metals, including gold, cobalt, zinc, tellurium and so-called “rare earths”, which are used in many electrical technologies, including smartphones, wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars and in high-strength, lightweight alloys used in aircraft, for example.

“These elements have all been identified as critical to our modern technology and the functioning of modern society,” said Murton.

The concentration of the metals is far greater than in ore rocks on land containing, for example, copper at 25-30%, compared to 2%.

The potential prize is great, said Murton: “The supply of rare earths is somewhat restricted at the moment, as 98% of the supply comes from China and they are very keen to maximise that scarce commodity for their own industry.

So there’s a kind of monopoly which makes it difficult for other countries.” Cobalt comes almost exclusively from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“There is overwhelming interest in the potential of these resources, which is why countries are really rushing to lay their claims,” Murton said.

Dozens of large areas have now been licensed in the open ocean, with the UK, Germany, France, Portugal, South Korea, Brazil, Russia and China among the nations involved, and almost all of the Atlantic ridge from the equator to the Arctic circle has been claimed in recent years.

“I think the technology capability [to mine] will be there in the next 5-10 years and I think there will be active commercial extraction in the same timeframe,” he said.

“I think it has the potential to be transformative for the commodities market.

It will have a significant impact on the global supply.” One Canadian firm, Nautilus Minerals, intends to start work on the sea bed near Papua New Guinea in 2018, although this may be delayed by funding difficulties.

The RRS James Cook expedition is part of a €15m (£12.5m) EU-funded research programme called Blue Mining, which also involves biologists and ecologists.

“They are tasked with really trying to understand what the environmental impact might be if these deposits are ever exploited commercially,” said Murton.

“There is absolutely no suggestion or enthusiasm from either scientists, or mining companies as far as I know, to go anywhere near the active hydrothermal systems,” said Murton.

“They are extraordinarily rich areas of unique species and ecosystems and we wouldn’t do anything to disturb those.”

Will McCallum, at Greenpeace UK, said: “The emerging threat of seabed mining is an urgent wake-up call for the need to protect the oceans.

The deep ocean is not yet mapped or explored and so the potential loss of fauna and biospheres from mining is not yet understood.

What we desperately need is a global network of ocean sanctuaries.”

Renowned ocean explorer Sylvia Earle is also concerned and said recently: “What are we sacrificing by looking at the deep sea with dollar signs on the few tangible materials that we know are there? We haven’t begun to truly explore the ocean before we have started aiming to exploit it.”

However, Murton said deep sea mining might be less environmentally destructive than mining on land.

“The deposits we are looking at sit on the seabed and are relatively easy to access.

In terms of disturbing the environment, the size of the whole, the amount of rock you have to move, crush up and throw away, it’s much smaller.

We wouldn’t have acid tailing pools like the one that burst in Brazil in 2015 or huge holes in the ground or forests that are cut down.”

The International Seabed Authority says its regulations give: “special emphasis to ensuring that the marine environment is protected from any harmful effects which may arise during mining activities, including exploration.”

Murton said the information from the Blue Mining programme will help policymakers decide whether these deposits could and should be exploited: “There are sensitivities around mining and always have been.”

Note: The article originally said the extinct vent systems are “devoid of life”.

They are devoid of typical vent species, but other species live there.

No comments:

Post a Comment