Weather record treasures await to be discovered :

Weather record treasures await to be discovered : C3S, WMO launch joint data rescue efffort portal

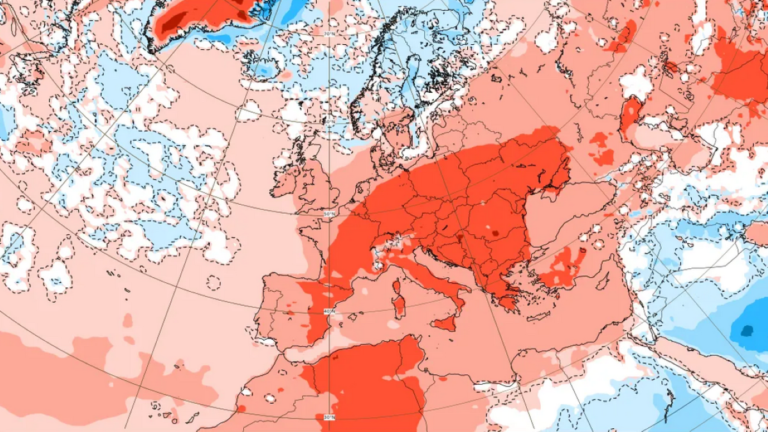

Data rescue is a relatively little-known field, but it is essential to complete our knowledge of the past climate, in particular in the most remote areas of the planet, where weather records are scarce.

Reanalysis datasets such as the Copernicus Climate Change Service’s ERA5 resolve these “gaps” with sophisticated computing operations, but the more information we have about the real conditions, the better the job it can do.

That’s why C3S is involved in Satellite Data Rescue and In situ Observations rescue operations.

On the occasion of the launch of a joint C3S-World Meteorological Organization data rescue portal, we take an in-depth look at these fascinating but sometimes overwhelming activities.On 22 June 1911, the

German cargo sailing vessel Peking left the harbour of Hamburg to reach Valparaiso, Chile, on 14 September.

This first trip, along with the following 19 trips made by the Peking for the F. Laeisz shipping company were carefully recorded in the meteorological “Tagebücher”, the ship logs.

The objective of these meticulous records was to gather information about the best shipping routes.

The Peking sailing on the Elbe estuary (Source: Stiftung Hamburg Maritim, © Hans Hartz)

The handwritten ship logs of the Peking, but also from meteorological stations across Germany and overseas were carefully

conserved by the German Meteorological Service, Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) for decades.

Millions of weather records have already been digitised and serve to improve our knowledge of the past weather, ingested in reanalysis datasets such as the

Copernicus Climate Change Service’s ERA5.

But millions of other meteorological records await.

That era of the pioneer weather data recording has left behind a legacy of tonnes, kilometres, entire rooms and buildings of climate data records in paper.

Now let’s multiply the case of DWD by the number of other meteorological services, agricultural associations, environmental agencies, research and exploration societies and other entities around Europe and the world.

Trillions of handwritten weather logs, that shed light on the past climate before the automated records and the satellite era, wait to be transcribed and ingested into the modern weather and climate datasets.

The task is colossal.

View of some shelves from the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany.

View of some shelves from the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany. Until now, WMO and C3S led the two main international initiatives to harmonise, share and gather old weather files.

Now the two organizations, with the cooperation of national weather agencies, have joined forces to present a unified portal under the leadership of the

Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI).

The new portal provides the tools, guidelines and access to global resources to set the standards and help international data rescue efforts move forward.

Paul Poli, C3S’ In-situ Observations Manager welcomes the arrival of the new portal.

“The data rescue community is a dedicated one and does not fear tackling such a daunting task.

In fact, the name they historically chose for themselves says more than a long story:

I-DARE, which is short for International Data Rescue.

We owe it to all the individuals involved, that we do everything we can to maximise the impact of their efforts.

By merging the activities with WMO and other international partners we are helping operationalise the operations and this will have a huge impact in the breadth, diversity, quality, and usability of the data.”

“There are many activities like ours, and they’re fragmented all over the world,” says Axel Andersson, from DWD’s Marine Climate Monitoring Division, “and the new portal gives an overview, a point where we can submit the data and make sure it will be used and provides a systematic way of submitting the data.”

“Integrating our activities will give us a global reach, and it was a natural fit,” said Peter Thorne, Professor of Physical Geography (Climate Science) that leads the C3S data rescue project.

KNMI was also a natural choice because it has supported the I-DARE community for years and it was involved in WMO data rescue.

“The objective is to provide a state-of-the-art set of guidelines and a centralised portal for our members, just to try to work more efficiently,” said Peer Hechler, leading the Data Rescue at WMO.

The new portal is an enabler, but “it requires people to actively participate in it, to register their projects, to keep abreast of their projects.

This joint portal is a part of the toolbox, but we need to do the hard yards of actually getting these data rescued, and that will happen through multiple methods and multiple groups,” stated Peter Thorne.

‘Scheepsjournaal van het Nederlandse schil Noordbeveland uit 1761’: logbooks of the Dutch vessel Noordbeveland from 1761.

‘Scheepsjournaal van het Nederlandse schil Noordbeveland uit 1761’: logbooks of the Dutch vessel Noordbeveland from 1761.

These logbooks contain precious meteorological information, on the condition of applying efficient methods to transcribe them.

Courtesy: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI)

Artificial intelligence and human intelligenceSome years ago DWD made an estimate of how long it would take to fully digitise all the data available in the German marine archive in Hamburg, and they came up with some impressive numbers: 300 person-years would be needed.

So, 300 people dedicated to digitising for a full year or one person for 300 years.

And this is the case for a single member of the 193 WMO members, even if data rescue operations sometimes don’t refer to centuries-old files.

“The data situations are very different around the world.

In Cambodia, for example, where I was on a mission, data rescue applies for the decade of the 2000s because their records from that period are still only available on paper and not digitised,” points out KNMI’s Gerard van der Schrier.

Only a few WMO member have the resources to tackle this almost “endless task”.

The rapid advances in artificial intelligence could mean a significant push for data rescue activities, but it is still challenging to read handwriting and correctly tabulate the data.

And a human is still needed to input the physical data records to the machine, in particular for century-old papers that require handling with additional care.

“There are huge opportunities coming down the line from AI and OCR (optical character recognition) technologies, which for a long time we thought would not be capable [of the task].

But in the last few months we have seen a sea change in that.

If you could get to the point where AI could do 80% or 90% and leave humans to verify and do the remaining 10% or 20% you would get to a whole new scale,” says Peter Thorne, who adds that the real bottleneck is digitalisation.

“Until these techniques are perfected, WMO still recommends to manually key in the data,” says Peer Hechler.

“I believe it will take some years to fully develop.

And AI won’t solve all the problems, because very often the archives are sitting on a shelf, those lucky ones that have a shelf, but nobody knows what’s in there.

Very often there’s very difficult work of sorting the archives that can only be done manually,” adds Hechler.

Data rescue is a field where citizen science and student initiatives have played an important role, given the amount of work needed and the relatively reduced resources available.

Anonymous contributors and weather passionate volunteers have helped digitise millions of observations and some initiatives have given rise to pages like

Old Weather, which has helped digitise data from Arctic exploration, whaling or World War II.

A recent example was the

Rainfall Rescue project, with some

16,000 volunteers digitising 5.2 million observations in just 16 days.

ACRE (Atmospheric Circulation Reconstructions over the Earth) and

IEDRO (International Environmental Data Rescue Organization) are some of the key international players in data rescue besides WMO, Copernicus and the national meteorological agencies.

“Data rescue involves a huge number of people, and there’s not a single modality,” says Peter Thorne.

Many data rescue volunteers become somehow addicted to log the files while discovering unheard weather events and meteorological conditions in the process.

Even if the personal and collective

citizen science initiatives are highly appreciated and necessary, data rescue operations need to be coordinated and to follow precise format rules and guidelines to be efficiently used and integrated into global datasets, which is the main ‘raison d’être’ of the new data rescue portal.

Much of the old meteorological data was saved on punch cards.

Much of the old meteorological data was saved on punch cards.

This is a picture of the archive of these punch cards.

It illustrates that progress of technology is a thread to safe and sustainable archiving of old data.

Courtesy: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI)Is it worth the effort?But why so much effort? Why undertake a mission that – even more before the arrival of AI— is deemed almost impossible to achieve? The reasons are many and varied.

Faced with a chaotic weather system, humanity has always kept track of the changes in weather, to try to better understand the best routes for trade, travel, the best geographical areas to settle in and more.

Axel Andersson reminds us that the early shipping logs were at the foundations of the International Meteorological Organization, the predecessor of the current WMO “already in the 19th century they started to exchange data to produce climatological charts.

This international data exchange system is still relevant today and is of

crucial importance for WMO.” he says.

The modern data rescue serves to support reanalysis, either by filling gaps or as a tool to verify the performance of a reanalysis dataset.

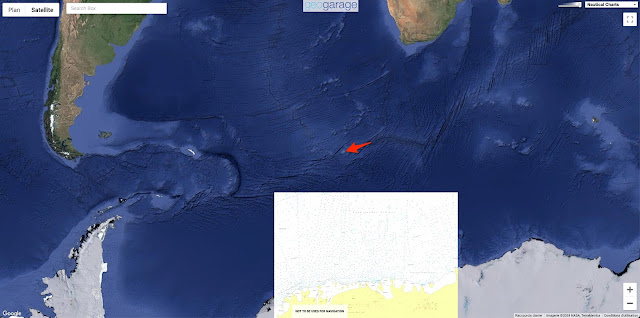

“The old data form data-sparse regions are particularly important.

It could have a big impact on regions where we don’t have any data.

We have input data collections for storm surges and storm floods in the 19th century.

It’s about learning from the past to understand the future,” says Axel Andersson.

Having previously been involved in the generation of century-long reanalyses, Paul Poli jumps on the question of whether focusing efforts on in-situ observations is not just a thing of the past, when today so many new satellites abound.

His response is an animation showing the evolution of the global observing system since 1940.

As the data coverage illustrates, the foundational role of in-situ observations is clearer.

“Improve this coverage, he adds, and the quality of reanalysis in the 1970s or before will improve for everyone using these data today – keep in mind we estimate that a quarter million people are using ECMWF reanalysis data, and if you count all the other reanalysis products, then globally this is probably far more.”

Observations assimilated in ERA5

Professor at Reading University Ed Hawkins, a great advocate of data rescue, and a dedicated data rescue volunteer himself,

demonstrated in 2022 how historical weather observations improved risk quantification for severe storms.

“Data rescue is one of the key priorities of WMO since its foundation, because our members have a lot of observations from the past, and for predicting our climate we need huge samples of observational data.

We need these observations to feed our computers in order to get a good analysis of the climate and develop climate models,” explains Peer Hechler.

Peter Thorne points out that, while climate models evolve thanks to the advances in computing and climate science, “the raw observations that inform all these wonderful datasets, including reanalyses, they are forever.

Without rescued data none of these state-of-the-art datasets would exist,” he says, “If we’re blind to the past we’re going to be surprised in the future.”

Data rescue also serves research, and not only in climate and weather but also in social sciences.

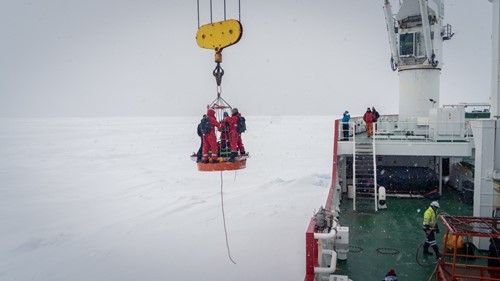

Beyond the clear benefits of ingesting the data into modern databases, there is also a sort of moral obligation face to the people that gathered those data, often at a great risk or in harsh conditions.

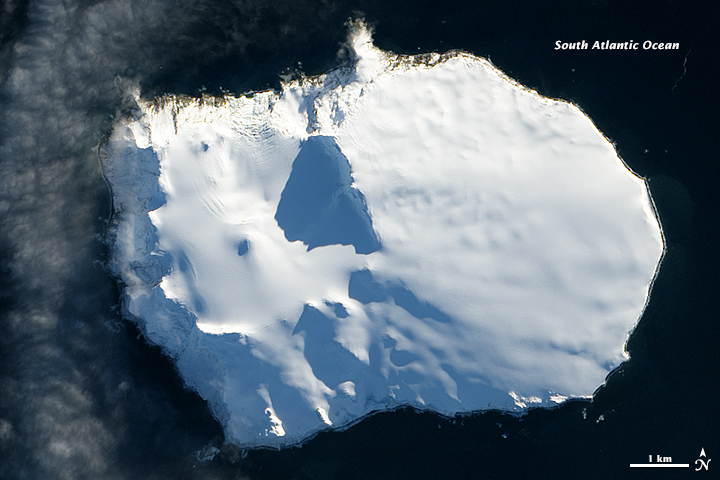

There was a time when gathering weather records was somehow heroic.

With heavy and rudimentary instruments and often in remote areas bashed by extreme weather, the early meteorology data observers would spend weeks or months gathering daily data records and maintaining their instruments in good shape.

KNMI’s Gerard van der Schrier said that one of the aspects that keeps him passionate about data rescue is to discover major weather events.

“You dive into those old records, and you discover events that you know about because they had an impact, and were told by the newspapers, for example hurricanes with impacts in crops or houses being lost.

Then looking at this data actually makes meteorology become alive, this gives you a vision on how a particular event developed and impacted a region,” said van der Schrier, citing the example of Indonesia, where there’s a lot of data because large farms kept weather records.

There are for example very detailed records of the eruption of the Krakatoa in 1883 that tell, at high resolution of how the weather and climate changed in the aftermath of the eruption.

“It gives a view that we didn’t have before, and I think that is the value of these old records.”

New portal, new perspectives for data rescueC3S and WMO expect that the

new portal will help national meteorological services, volunteers and researchers give a new impetus to data rescue activities.

“I'm quite happy about the last two or three years when we worked closely together with Copernicus as well as with our other global partners like IEDRO and ACRE.

We all came together and try to bundle our resources and try to provide to the world single solutions, a single portal and a single set of guidelines.

I believe this was much needed,” concludes Peer Hechler.

“It is great to see the data rescue community coming together to maximise the efforts.

The new perspectives opened by artificial intelligence can be a game changer for data rescue activities around the world.

We are very excited with merge of this activity together with WMO and we hope we will receive millions of additional observations that we didn’t know about before,” said Paul Poli.

Peter Thorne agrees: “Creating data that’s usable as a global archive is a huge undertaking but it’s hugely necessary.”

Links :

Submarine crews of around 130 people share four sinks and three toilets, with little to no contact with the outside world - 'it's challenging', admits Captain Ryan Ramsey

Submarine crews of around 130 people share four sinks and three toilets, with little to no contact with the outside world - 'it's challenging', admits Captain Ryan Ramsey

Weather record treasures await to be discovered :

Weather record treasures await to be discovered :

View of some shelves from the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany.

View of some shelves from the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany.  ‘Scheepsjournaal van het Nederlandse schil Noordbeveland uit 1761’: logbooks of the Dutch vessel Noordbeveland from 1761.

‘Scheepsjournaal van het Nederlandse schil Noordbeveland uit 1761’: logbooks of the Dutch vessel Noordbeveland from 1761. Logbook of a German ship kept at the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany.

Logbook of a German ship kept at the DWD Maritime Archive in Hamburg, Germany. Much of the old meteorological data was saved on punch cards.

Much of the old meteorological data was saved on punch cards. Credit : contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017), processed by ESA

Credit : contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017), processed by ESA