From The New York Times by Manohla Davies

A taut moral thriller, “Styx” is a story of what happens when self-reliance runs into other people’s desperation.

The lives of others don’t seem of much concern to a German doctor, Rike (Susanne Wolff), when she sets off on her adventure.

Alone on a 30-foot sailing yacht, she is headed to Ascension Island, a mid-Atlantic speck roughly halfway between Africa and South America.

With grit, provisions and a pretty coffee-table book about the island that suggests her romanticism, or perhaps naïveté, Rike is following Charles Darwin to Ascension.

It’s a dream journey that will slam into the refugee crisis.

One woman’s dream can look like someone else’s worst nightmare, even if the director Wolfgang Fischer initially makes Rike’s passage into existential isolation seem inviting.

After a brief, eloquent preamble in Germany, he deposits Rike in Gibraltar, where she efficiently packs up her boat.

Much like his protagonist, Fischer assumes a well-organized, seamless approach to his launch, setting the scene with a bright, direct visual style that feels largely informational — a lingering shot of what appears to be months’ worth of food and water — and only occasionally slides into the metaphoric, as when Rike sails past a gargantuan tanker that conveys an ominous dehumanization.

Part of the allure of this expedition is its quietude, at least for the audience.

Soon after Rike leaves Gibraltar, she is enveloped by the ocean, and the movie shifts into the visual and auditory minimalism that defines its alluring, almost hypnotically soothing first third.

Fischer primarily shot “Styx” on the open sea, with Malta standing in for the west coast of Africa.

It’s a headily seductive landscape painted in every conceivable shade of blue and daubed with white.

Like Rike, you settle into the luxurious peacefulness, a stillness augmented by the water’s rhythmic splashes, her bustling movements and the boat’s gentle cacophony — the flap of the sails, the whir of the winch, assorted pleasant creaks.

Excursions into solitude invariably must end, especially when there’s another hour or so of movie yet to come.

Civilization intrudes on Rike’s seclusion when a man’s voice begins squawking on her radio.

It’s a friendly, ever-so-slightly paternalistic intrusion.

He provides an extreme weather forecast and promises future help if she should ever need it.

A no-nonsense woman who seems perfectly capable of taking care of herself, Rike politely accepts the offer.

Still, there’s something about the exchange that seems to irk her (and you), partly because the movie is playing with the figure of the independent modern woman, one who seems capable of handling any reasonable challenge.

Susanne Wolff plays a doctor who sets off on a high-seas adventure in “Styx.”

Susanne Wolff plays a doctor who sets off on a high-seas adventure in “Styx.”

The violent storm that soon descends precedes a dramatic narrative shift — after the weather clears, Rike sees a fishing trawler overloaded with passengers.

(They’re between Cape Verde and Mauritania.)

Because the camera continues to share her point of view — and the trawler is distant enough — you hear voices but can’t make out faces, just bodies and frantically waving arms.

Rike sends out a distress signal.

Her boat is too small to save all the passengers, who she worries will panic and scramble onboard, sinking it.

One voice after another answers back, a clamor of international strangers who sternly tell her to do nothing and wait for help.

Rike waits and waits some more.

In short order, the larger world crashes in, and a story of radical, deeply privileged individualism gives way to a potent, messy and sometimes uncomfortable parable about what human beings owe one another.

The refugees are adrift on a sea of global indifference.

Fischer puts a human face on the crisis through the introduction of a boy in his early teens (Gedion Oduor Weseka), who swims to Rike’s boat, almost drowning.

Pulling him out of the water, Rike calls him Kingsley (the name on his bracelet), and they begin a wary relationship that movingly if schematically personalizes a larger social struggle.

Fischer’s minimalism isn’t simply a stylistic choice; it’s also strategic.

The story of an advantaged European face to face with desperately imperiled African refugees seems tailor-made for political pieties and the dubious enshrinement of one more white savior story.

For the longest time, though, Fischer, working with a script that he wrote with Ika Künzel, refuses to preach or tip his political hand.

Instead he focuses on the physical dangers and bodily assaults that Kingsley and Rike endure as the voices on the radio continue promising help and the voices from the boat eerily begin to dim.

Rike’s stoic competence and Wolff’s attractive, contained performance have led you to think that she can handle anything, a fantasy that is as reassuring as it is grimly, horrifically false.

Links :

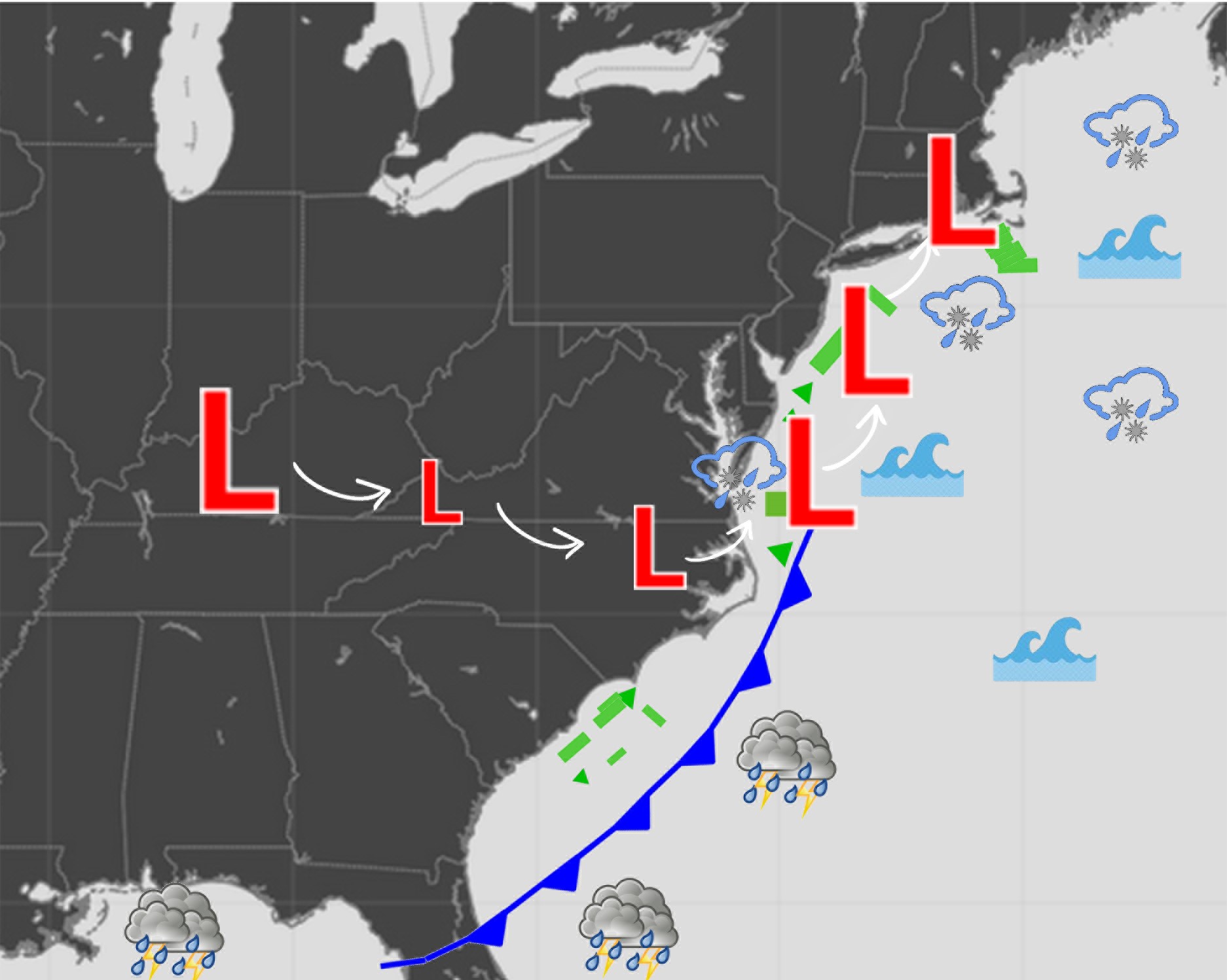

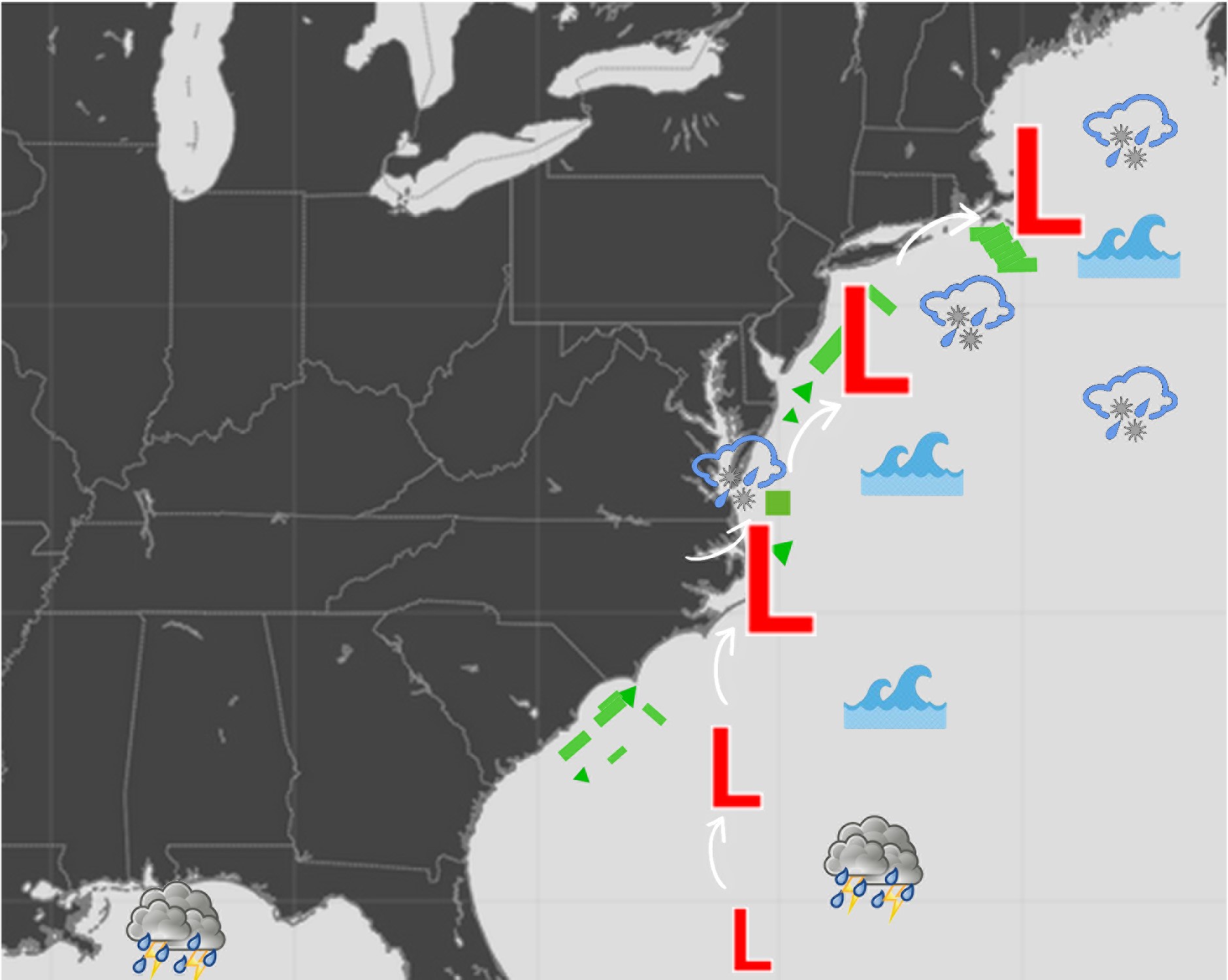

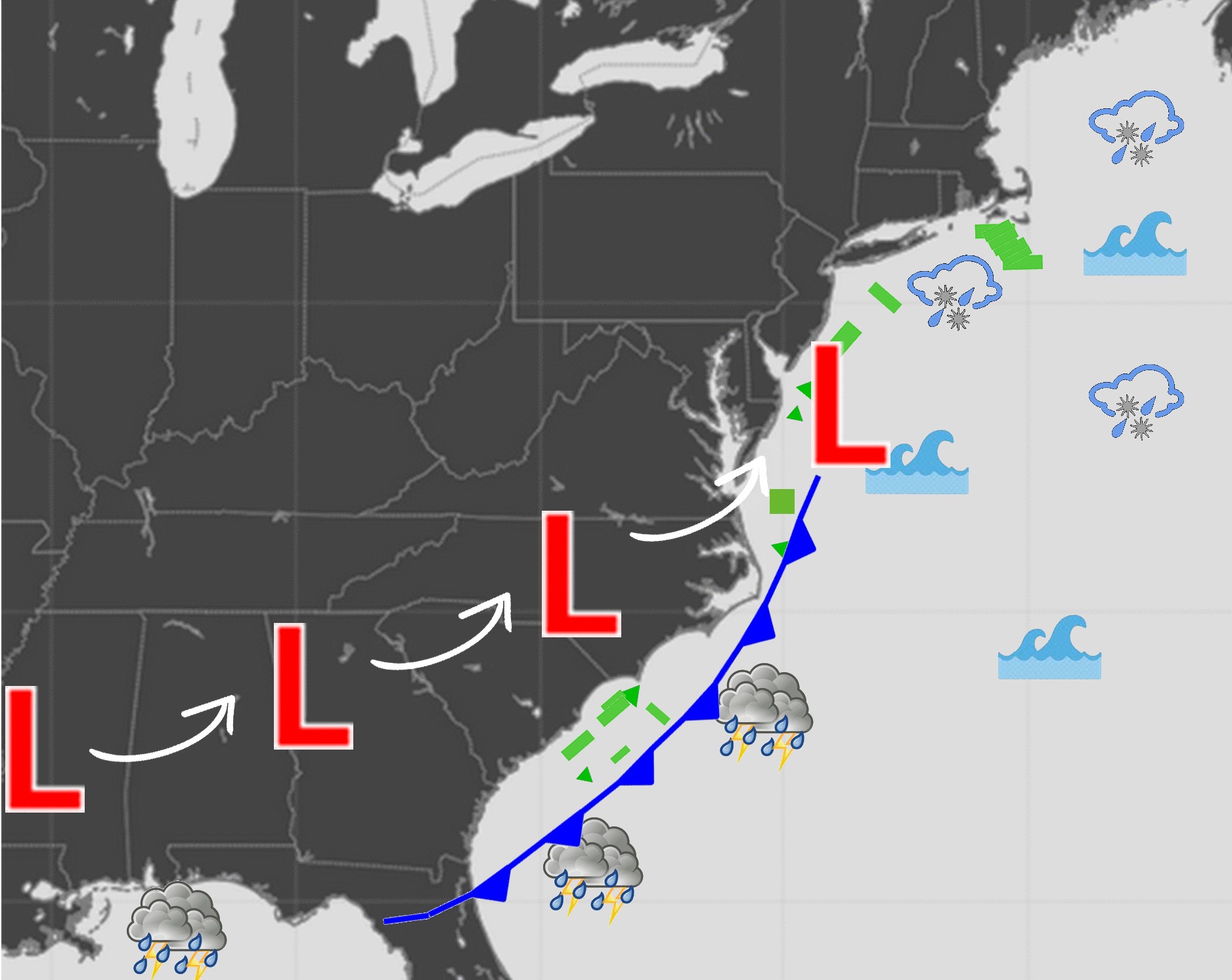

Figure 1: Type A storm

Figure 1: Type A storm