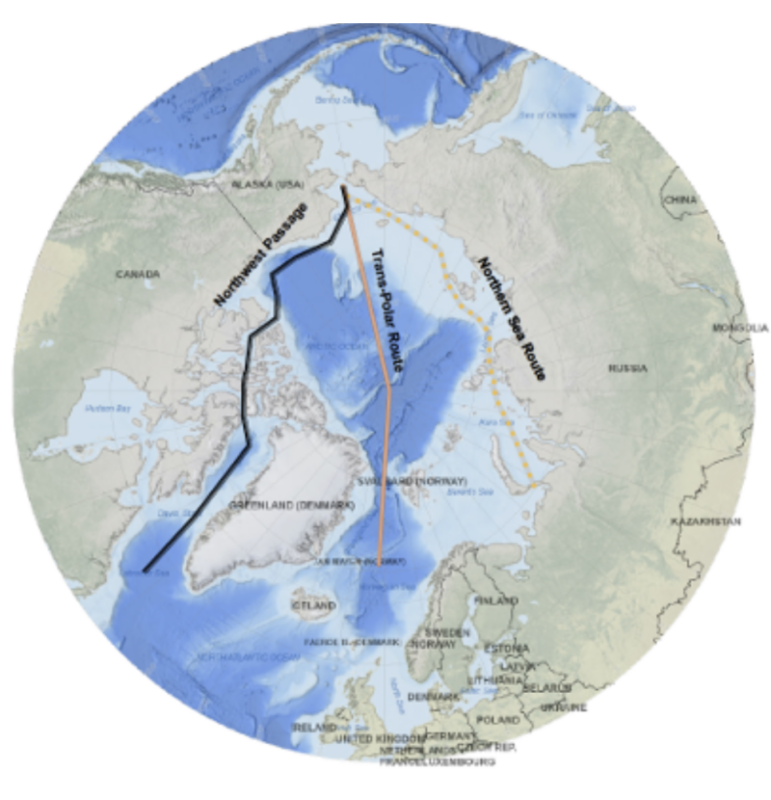

Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) in polar environments.

SAI in

polar regions will not be possible year-round, due to winter darkness,

and may have unwanted and unintended consequences for regional climates,

including those across territorial boundaries.

The pale blue shading

shows the effective time period for SAI in the Arctic.

The Inset icons

(bottom right) show whether the option has been proposed for Antarctica,

the Arctic, or both.

Proposals will not help and could harm, according to new assessmentA team of international scientists is urging caution against five of the most-discussed polar geoengineering ideas, stating they are highly unlikely to help the polar regions and could harm ecosystems, international relations, and reduce our chances of reaching net zero by 2050.

These findings are outlined in

a new assessment, published Sept. 9 in Frontiers in Science, which looked at several of the most developed geoengineering proposals currently being considered for use in Antarctica and the Arctic.

Led by the University of Exeter in England, the assessment was a collaborative effort involving co-authors from more than 30 organizations and universities, including UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The project was initiated in early 2024, when this group of global experts came together to take a hard look at the major geoengineering ideas being proposed.

“We dug into all the relevant research and literature on polar geoengineering, and what we found was clear: none of the concepts stood up to scrutiny when it came to real-world feasibility or chances of success.

In fact, most of them are more likely to be environmentally dangerous, causing more harm than they seek to solve,” said Scripps Oceanography glaciologist Helen Amanda Fricker, one of the founding authors of the study and current director of the

Scripps Polar Center.

The polar regions are home to fragile communities and ecosystems, as well as most of the world’s ice.

Technological ‘geoengineering’ approaches have been proposed to delay or address the impacts of climate breakdown in these regions.

Yet this new paper finds that five polar geoengineering proposals are likely to cost billions in set-up and maintenance, while reducing pressure on policymakers and carbon-intensive industries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The proposals were also found likely to introduce additional ecological, environmental, legal and political problems.

"These ideas are often well-intentioned, but they‘re flawed.

As a community, climate scientists and engineers are doing all we can to reduce the harms of the climate crisis — but deploying any of these five polar projects is likely to work against the polar regions and planet,” said lead author Martin Siegert, a glaciologist at the University of Exeter.

"If we instead combine our limited resources towards treating the cause instead of the symptoms, we have a fair shot at reaching net zero and restoring our climate’s health,” said co-author Heidi Sevestre, a glaciologist working with the Secretariat of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme.

The proposals

Sea curtains to block warm water from flowing towards ice sheet

grounding zones. Installing structures spanning many tens of kilometers

is a massive technological challenge that will require operations across

some of the world’s roughest seas and sustained work in ice-covered

locations that even modern ice-strengthened vessels cannot always reach.

These curtains will probably have unwanted consequences on ocean

circulation and ecosystems.

The pale blue bar shows the relatively short

operational window for ships in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica.

The Inset

icons (bottom right) show whether the option has been proposed for

Antarctica, the Arctic, or both.

To conduct the new assessment, the researchers looked at five geoengineering approaches that have received the most attention to date:stratospheric aerosol injections (SAI): releasing sunlight-reflecting particles such as sulfate aerosols into the atmosphere to reduce the sun’s warming effect;

sea curtains/walls: flexible, buoyant structures anchored to the seabed that aim to prevent warm deep water from reaching and melting ice shelves;

sea ice management: artificially thickening ice by pumping seawater onto it, or scattering glass microbeads on remaining sea ice to increase its reflectivity;

basal water removal: pumping subglacial water away from underneath glaciers in an effort to slow ice sheet flow and reduce ice loss;

ocean fertilization: adding nutrients such as iron to polar oceans to stimulate blooms of phytoplankton — microscopic creatures that draw carbon into the deep ocean when they die.

The team measured each proposal against their likely scope of implementation, effectiveness, feasibility, negative consequences, cost and existing governance frameworks that would allow timely deployment at scale.

They also assessed each proposal’s potential appeal to those vested in avoiding emissions cuts.

According to the assessment:

Effectiveness and feasibility: None of the ideas currently benefit from robust real-world testing.

No field experiments exist for sea curtains or sea ice reflection.

SAI has only been tested with computer modelling, ocean fertilization experiments were inconclusive, and glacier water removal has not been demonstrated beyond limited drilling.

The polar regions are some of the world’s harshest environments to work in, and even simple logistics are challenging to deploy.

The scale of polar geoengineering would require a human presence in the polar regions unlike anything we have considered to date, and many proposed ideas do not take these challenges into consideration.

Negative consequences: All proposals would bring intrinsic environmental damage, and sea ice management also carries major ecological risks, such as glass beads darkening the ice, and water pumps requiring vast infrastructure.

The risks of SAI include ozone depletion and global climate pattern change.

Sea curtains risk disrupting habitats, feeding grounds and the migration routes of marine animals, including whales, seals and seabirds.

Glacier water removal risks contaminating subglacial environments with fuels, and ocean fertilization carries uncertainty as to which organisms will flourish or decline, as well as the potential for triggering shifts in natural ocean chemical cycling.

Cost: The authors estimate that each proposal will cost at least $10 billion to set up and maintain.

Among the most expensive are sea curtains, projected at $80 billion over 10 years for an 80-kilometer (50-mile) structure.

(For context, the approximate perimeter of Antarctica is 53,610 kilometers (33,312 miles) and the approximate perimeter of Greenland's coastline is 44,087 kilometers (27,394 miles).

They caution that these costs are likely underestimates, and warn that they will be higher still once knock-on consequences, such as environmental and logistical impacts, are included.

Governance: No governance frameworks exist to regulate SAI or sea ice management.

Sea curtains and glacier water removal would fall under Antarctic Treaty provisions, while ocean fertilization is treated as marine pollution and restricted under United Nations rules.

All proposals would require extensive political negotiation and the creation of new governance structures and infrastructure.

Scale and timing: The authors conclude that, even if the proposals offered some benefit, none can be deployed at sufficient scale, and fast enough, to tackle the climate crisis within the limited time available.

Vested interest appeasement: The authors found that all proposals risk appealing to those seeking to avoid emissions cuts.

They note that claims about sea ice management preserving Indigenous Peoples’ rights and environments are misleading, and stress that only rapid decarbonization can achieve this without the risks.

Using glass beads as a means to reflect sunlight off polar surfaces.

Changing albedo by adding particles to the ocean may actually decrease

albedo, would require deliberate pollution of ecosystems, and may cross

governance boundaries.

It is also unlikely to be logistically possible

to operate at the scale necessary to make a significant difference.

The

inset icons (bottom right) show whether the option has been proposed for

Antarctica, the Arctic, or both.

Split resources

Geoengineering is a divisive topic among experts.

Some cite large uncertainties in effectiveness, risks of negative consequences, and major legal and regulatory challenges.

Others argue that geoengineering could buy time while the world cuts emissions, and warn against dismissing proof-of-concept research.

Arctic sea-ice thickening to counteract the loss of ice.

Techniques to

thicken sea ice would require a very large number of individual devices

to be deployed onto the winter sea ice, and it is unlikely to be

logistically possible to operate at the scale necessary to make a

significant difference.

The inset icons (bottom right) show whether the

option has been proposed for Antarctica, the Arctic, or both.

Although the authors acknowledge the importance of explorative research, they say that continuing to pursue these five polar geoengineering proposals could shift focus from the urgent systemic change needed to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

This, they argue, risks splitting monetary and research resources when time is of the essence.

"Mid-century is approaching, but our time, money and expertise is split between evidence-backed net zero efforts and speculative geoengineering projects,” said Siegert.

“We're hopeful that we can eliminate emissions by 2050, as long as we combine our efforts towards reaching zero emissions."

"While research can help clarify the potential benefits and pitfalls of geoengineering, it’s crucial not to substitute immediate, evidence-based climate action for as-yet unproven methods,” said Sevestre.

“Crucially, these approaches should not distract from the urgent priority of reducing emissions and investing in proven mitigation strategies.”

Subglacial water removal in ice sheets to slow ice flow to the ocean. Drilling to the bed of thick, flowing ice is highly technologically

challenging and has never been undertaken for the sustained period

required to maintain the drainage of subglacial water.

Subglacial

drainage networks are currently pristine and not well mapped, so the

introduction of drill holes into the network will probably be highly

challenging to achieve reliably and could cause contamination both below

and above the ice.

The inset icons (bottom right) show whether the

option has been proposed for Antarctica, the Arctic, or both.

Ocean fertilization to “draw down” atmospheric CO2. Negative

impacts will likely include changes to food web structure, and

fertilization could affect nutrients and fisheries elsewhere, including

across territorial or governance boundaries. The inset icons (bottom

right) show whether the option has been proposed for Antarctica, the

Arctic, or both.

They note that while their assessment focuses on the polar areas, other geoengineering ideas, such as marine cloud brightening and space-based solar reflectors, also need to be assessed against these criteria.

“The good news is that we have existing goals that we know will work.

Global heating will likely stabilize within 20 years of us reaching net zero.

Temperatures would stop climbing, offering substantial benefits for the polar regions, the planet and all lifeforms,” said Siegert.

A total of 42 researchers from 36 organizations co-authored the assessment.

While the study received no direct funding, individual researchers are supported by various funders, including Fricker’s work, which was funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt.

The full list is available

in the study.

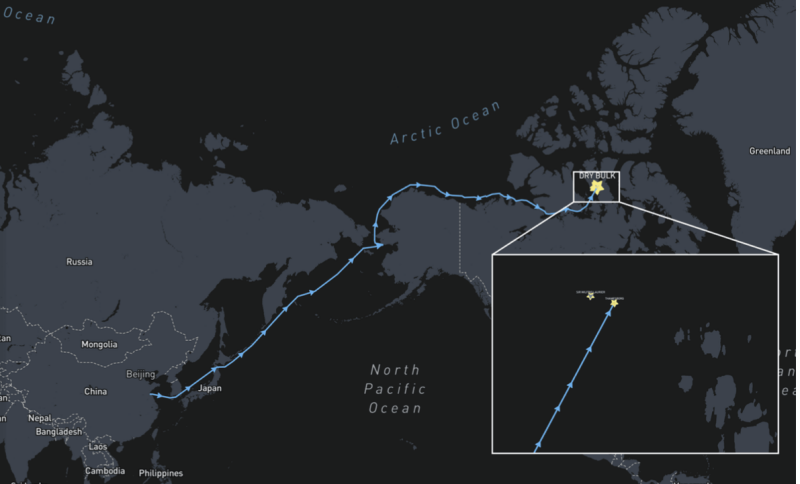

Thamesborg’s route from China to the Canadian Arctic and the vessel’s location in the Franklin Strait with CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier in proximity.

Thamesborg’s route from China to the Canadian Arctic and the vessel’s location in the Franklin Strait with CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier in proximity.