Saturday, August 16, 2025

Friday, August 15, 2025

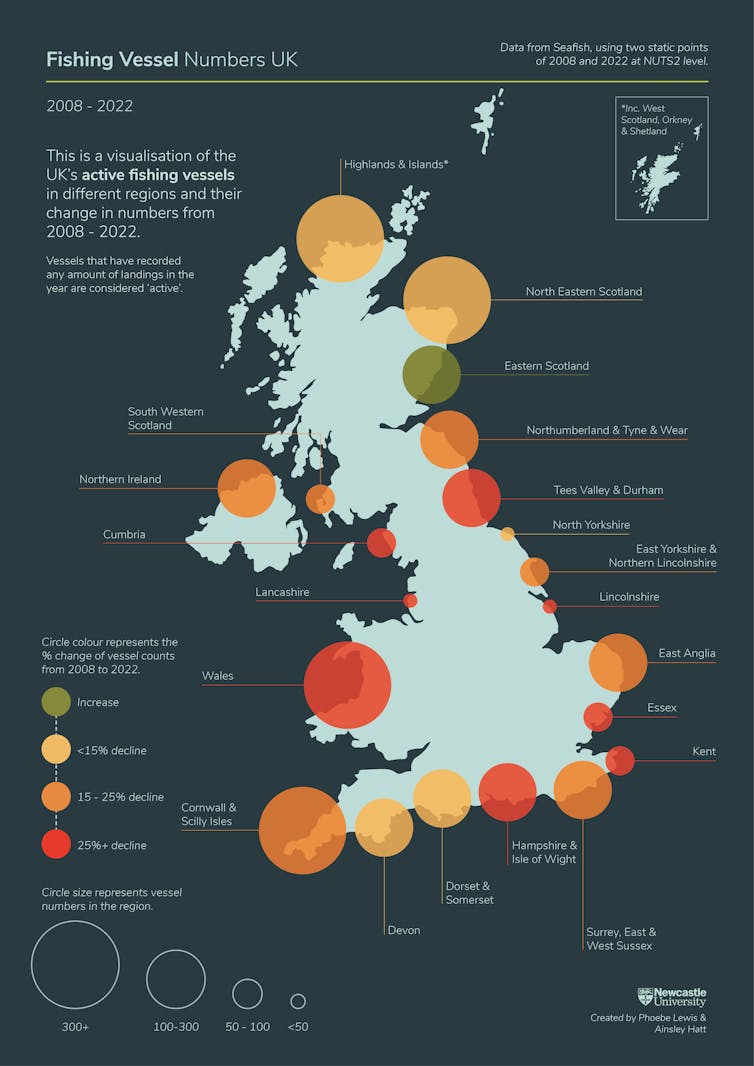

The UK is losing its small fishing boats – and the communities they support

A way of life at risk: a small fishing boat is pulled along Cromer beach in north Norfolk.

Ian Georgeson/Ian Georgeson Photography

From The Conversation by Phoebe Lewis

If you walk the harbour in Hastings in south-east England or the beach further north in Cromer at dawn, you’ll see the signs of a centuries-old way of life: small boats landing their fresh catch and crews unloading crates of crab, lobster or bass.

But there are fewer boats than a generation ago, fewer working fishers, and fewer incentives for young people to enter the industry.

What was once the beating heart of a coastal community is at risk of becoming a memory in many areas.

Inshore and small-scale fishing boats are those vessels that fish predominantly within 6 nautical miles of the coastline and are usually under 10 metres in length.

Inshore and small-scale fishing boats are those vessels that fish predominantly within 6 nautical miles of the coastline and are usually under 10 metres in length.

They make up nearly 80% of the UK fishing fleet.

Since they operate close to shore, these boats supply local markets and often land directly onto beaches and into small harbours.

Inshore fisheries don’t just catch fish, they sustain local economies, cultures and ways of life – but they are disappearing.

Research conducted by ourselves and colleagues confirms that the entire fleet is in decline across the UK.

Research conducted by ourselves and colleagues confirms that the entire fleet is in decline across the UK.

However, this decline is being unevenly felt around the country.

In England alone, between 2008 and 2022, 495 active fishing vessels were lost, equivalent to 20% of the total.

In England alone, between 2008 and 2022, 495 active fishing vessels were lost, equivalent to 20% of the total.

Smaller boats were hit hardest: vessels less than 10 metres long declined by 22% – nearly double the 13% fall in larger boats.

These losses are even more severe when fishing activity is taken into account.

These losses are even more severe when fishing activity is taken into account.

Days at sea for the under-10 metre fleet fell by 44%, and employment dropped by nearly half (47%).

An uneven distribution of fishing boat decline can be seen across the UK.

These numbers don’t just reflect a shrinking fleet.

Smaller vessels are less able to fish further afield in response to changing fish stocks, bad weather or increasing pressure from other sea users.

This suggests that inshore and small-scale fishing families bear a disproportionate share of the challenges faced across the entire fleet.

And once the last boat has gone from a harbour, with all the knowledge of where and how to fish, it is a way of life that could be lost forever.

And once the last boat has gone from a harbour, with all the knowledge of where and how to fish, it is a way of life that could be lost forever.

Why are we losing boats?

The reasons for the decline are complex and shaped by local contexts.

Competition for space, restricted access to fishing grounds, insufficient quotas to target diverse fish stocks, limited access to markets, an ageing workforce – all of these things contribute.

But there is a deeper problem: a policy framework that prioritises fish stocks and economic yield over people and places.

Too often, fisheries policy in the UK and internationally has focused on sustainability as predominantly a biological problem.

Too often, fisheries policy in the UK and internationally has focused on sustainability as predominantly a biological problem.

Are fish stocks recovering?

Are total catch levels within safe limits?

These are important questions, but they miss half the story.

A fishery is not just an ecosystem, it’s a community.

A fishery is not just an ecosystem, it’s a community.

The people who fish, mend nets, manage harbours and sell seafood are integral to the sustainability of coastal life.

Without them, we lose not just jobs but a whole chain of economic and social support.

Fish processors, boat builders, local shops and, in more rural or island locations, even the basic viability of essential services like schools and healthcare can depend on the continued presence of fishing families.

While small-scale fisheries may be marginal from the perspective of national GDP, fewer boats often means fewer families – and the erosion of a community which makes a seaside town more than just a tourist backdrop.

While small-scale fisheries may be marginal from the perspective of national GDP, fewer boats often means fewer families – and the erosion of a community which makes a seaside town more than just a tourist backdrop.

As fishing fades, so too does a sense of local character and identity: elements that distinguish these towns and connect them to their maritime heritage.

What would it take to stem the loss?

A number of solutions are frequently discussed, including quota systems designed to meet community needs, improved harbour facilities for small boats, more visible training opportunities and clearer pathways for young people to enter fishing.

Inshore and small-scale fishers also need to have their voices heard, and to trust their experiences and insight will help shape the future of coastal communities.

But lasting change also requires a shift in mindset: to see fishing not just as a source of seafood but as part of a sustainable future for coastal Britain.

Fishermen in Cromer, north Norfolk.

Fishermen in Cromer, north Norfolk.The UK government has an important role to play in recognising and addressing the challenges faced by smaller vessels.

This aligns with international commitments the UK has already made to support small-scale fisheries, which call for the fair distribution of marine resources and protection of cultural heritage.

But it is not just policymakers who can make a difference.

But it is not just policymakers who can make a difference.

Buying locally landed fish, supporting fishing festivals, learning about local seafood and simply chatting to fishers on the beach or at the harbour – these small acts all help show that people value this work and want it to continue.

The small fishing boats still seen bobbing in UK harbours are more than working vessels – they are signs of a living culture.

The small fishing boats still seen bobbing in UK harbours are more than working vessels – they are signs of a living culture.

For those willing to learn the trade, fishing offers a viable independent livelihood and a strong connection to community and the sea.

If we want our coastal communities to thrive, not just survive, action is required before the last boats leave the shore for good.

If we want our coastal communities to thrive, not just survive, action is required before the last boats leave the shore for good.

Thursday, August 14, 2025

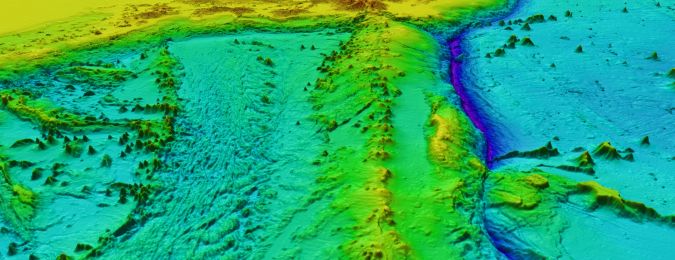

The many ways we discover the hidden seabed

Mapped

seafloor regions are depicted in blue, whereas red denotes the latest

bathymetric measurements acquired during the past year.

Mapped

seafloor regions are depicted in blue, whereas red denotes the latest

bathymetric measurements acquired during the past year. (Image courtesy:

Seabed 2030)

From Hydro

Seabed 2030 represents more than a technical milestone

From the earliest voyages across uncharted waters, the ocean floor has stirred human curiosity.

Despite breakthroughs on land and in space, the seabed remained one of Earth’s final frontiers.

In 2017, only 6% of the global ocean floor was mapped to modern standards.

By mid-2024, this figure rose to over 26%, and as of June 2025, Seabed 2030 announced that 27.3% of the seabed is now mapped.

An additional four million km² – roughly the size of the Indian subcontinent – has been unveiled.

Central to this effort are multibeam echosounders (MBES), powerful acoustic systems installed on research and commercial vessels.

These devices emit fan-shaped pulses that chart detailed underwater landscapes, revealing mountains, canyons and plains essential for safe navigation, biodiversity studies and resource management.

Yet even these advanced systems cannot keep up with the vastness of the oceans alone.

Autonomy is key

To meet this challenge, uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) have become vital.

Powered by wind and solar, USVs such as Saildrone’s Surveyor can travel autonomously across entire ocean basins without crew on board.

These vessels have already mapped thousands of square kilometres of previously unknown seabed, greatly expanding the reach of traditional survey fleets.

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) play an equally important role.

Moving silently through deep canyons and across abyssal plains, they explore places beyond the reach of ships.

Equipped with compact sonar systems and sophisticated navigation, these vehicles are essential for tackling the most remote and complex underwater landscapes.

Their ability to operate for long durations and at great depths makes them invaluable for filling the hardest-to-reach gaps.

Strategic layer

Satellite-derived bathymetry adds another strategic layer.

By analysing how light penetrates shallow coastal waters, satellites can estimate depths across large areas and provide quick first impressions where no direct surveys exist.

Although less precise than acoustic methods, this approach opens opportunities for more detailed follow-up surveys and helps to accelerate global coverage.

Collaborations with firms such as EOMAP and TCarta have further advanced this method, producing grids as fine as ten metres in clear, shallow waters – often down to depths of around 20 to 30 metres.

Beyond filling critical gaps, satellite-derived bathymetry supports environmental monitoring, including mapping coral reefs and seagrass beds, and allows for rapid, low-impact mapping even in remote or politically sensitive regions.

Capacity-building initiatives, such as TCarta’s training programmes, enable coastal nations to generate and share their own data, strengthening both regional mapping efforts and local stewardship of marine environments.

The oceans cover over two thirds of our planet, and it is often said that we know more about the shape of the surface of Mars than we do about that of our global seafloor.

Seabed 2030, a collaborative project between GEBCO and the Nippon Foundation, seeks to address this gap by facilitating the complete mapping of the global ocean floor by the year 2030.

(Image source: Seabed 2030)

Crowdsourced data

Beyond these high-tech solutions, crowdsourced data has become an increasingly powerful force.

Commercial ships, fishing vessels and private yachts gather depth measurements as they travel.

When combined, these everyday contributions form a valuable patchwork that reveals new features along heavily used routes and contributes to a better overall understanding of the seabed.

Taken together, these methods illustrate a sector in transformation.

The hydrographic community now acts as a global network of sophisticated sensors, autonomous platforms, satellite technology and volunteer contributors, all working together to uncover the shape of the ocean floor.

This collaborative spirit marks a new era in ocean science, one driven by innovation and a shared sense of responsibility.

Growing global engagement

Recent progress highlights this shift.

At the 2025 UN Ocean Conference in Nice, marine experts and world leaders underscored the importance of bathymetric data for supporting the blue economy, improving coastal resilience and guiding biodiversity and climate strategies.

Seabed 2030 also welcomed contributions from 14 new organizations, including first-time data from Comoros, Cook Islands, Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania.

The total number of contributors now exceeds 185, a testament to growing global engagement.

Despite this momentum, around 72.7% of the ocean floor remains unmapped to modern standards.

Many of the remaining areas lie in deep-sea or polar regions, where harsh conditions and high costs present ongoing challenges.

Nevertheless, advances in autonomy, data processing and international collaboration offer hope that the gap will continue to close.

The story of Seabed 2030 so far is deeply inspiring, as highlighted in recent coverage by Hydro International.

The hydrographic industry has already come a long way, evolving from sailors lowering lead lines into the water to a global effort involving autonomous surface and underwater vessels, satellites and crowdsourced data.

Although much work remains, Seabed 2030 represents more than a technical milestone; it embodies a shared vision that unites scientists, industry and nations.

This initiative not only drives progress but also sparks innovation and strengthens collaboration.

The ocean floor remains one of Earth’s greatest mysteries, but each new discovery – now with nearly 30% mapped – brings humanity closer to fully understanding the depths that shape the planet.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog :

Seabed 2030 announces millions of square kilometers of new ... /

Seabed 2030's invaluable journey /

Putting Portugal on the (seabed) map with the SEAMAP ... /

Tropical seafloor secrets discovered as seabed 2030 gains ... /

'The Deepest Map' explores the thrills — and dangers

The mighty quest to unveil our blue planet /

Nearly a quarter of Earth's seafloor now mapped /

Can a map of the ocean floor be crowdsourced? /

The ocean is deeper than you think. We need better maps. /

Mapping quest edges past 20% of global ocean floor /

An ambitious project aims to map the entire ocean floor. It ... /

Earth's final frontier: the global race to map the entire ... /

To predict future sea level rise, we need accurate maps ... /

Mappers look to chart world's ocean floor by 2030 /

Why mapping the entire seafloor is a daunting task, but key ... /

Why the first complete map of the ocean floor is stirring ... /

Model suggests undersea mountains help mix the global ... /

High-tech seafloor mapping is finding surprising structures ... /

NOAA Ocean Exploration meets major mapping milestone ... /

Massive new seamount discovered in international waters ... / Mapping the mysteries—and the dangers—of the ocean ... /

Wednesday, August 13, 2025

Private companies are now gathering weather data for NOAA

PHOTOGRAPH: WINDBORNE SYSTEMS

From Wired by Meg Wilcox

WindBorne Systems is one of several companies launching balloons, drones, buoys, and other devices to provide critical data to the beleaguered agency’s National Weather Service, but they can’t fill all the gaps.

THIS STORY ORIGINALLY appeared on Inside Climate News and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

When staffing shortages caused the National Weather Service (NWS) to suspend weather balloon launches at its Kotzebue, Alaska, station earlier this year, a startup deploying next-generation weather balloons, WindBorne Systems, stepped up to fill the void.

The company began selling its western Alaskan atmospheric data to the NWS in February, plugging what could have been a critical data gap in weather forecasting.

Weather balloons collect real-time atmospheric temperature, humidity, wind speed, and pressure data that meteorologists use to predict the weather and understand longer-term changes to the climate.

The Alaska office was one of about a dozen to suspend or scale back balloon launches in response to deep staffing cuts instituted by the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

Critics claim that the cuts have weakened the NWS’s forecasting capacity as hurricane season bears down and extreme weather events, like the floods that ripped through Texas, claim lives and destroy property.

As the beleaguered weather service struggles to maintain its forecasting and other services, it’s leaning on private companies to pick up the slack.

For example, WindBorne, which is backed by Khosla Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on investing in companies with innovative business models and technologies, is opening five new balloon launch sites in the US this year as it expands its work with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the parent agency of the NWS.

“We’re flying more balloons every day and collecting more observations to help improve forecasts in light of some of these systems going down,” said John Dean, WindBorne’s cofounder and CEO.

Sofar Ocean, Tomorrow.io, Black Swift Technologies, and Saildrone are among other startups with innovative technologies and AI forecasting models that are increasingly supplying NOAA with critical atmospheric and oceanic data through its Mesonet Program.

Such collaboration isn’t new, but former NOAA officials worry that the current administration, with its zeal for privatization, will jettison core federal observing systems and rely instead on private sector data to forecast the weather.

While they lauded the companies’ innovations, they said that NOAA must maintain ownership of its “backbone” data assets like weather balloons to ensure public safety and maintain the historical climate record.

New technologies, they said, should supplement NOAA’s core data collection efforts rather than replace them wholesale.

“NOAA has always had a robust relationship with the private sector exactly for the sorts of things that WindBorne does,” like innovate and supply data, said Tom Di Liberto, a meteorologist and former NOAA spokesperson who is now media director at Climate Central.

Under the current administration, however, “the concern is, what is it going to replace?”

If private services take the place of, rather than supplement, the agency’s core data assets, that could prove problematic, because “less data is bad,” he said.

“Are we actually saving money or just giving taxpayer dollars to a private company?”

Data as a Service

In the past NOAA bought sensors and hardware from companies with promising innovations to bring the technology in house.

More recently, it’s adopted a model of “data as a service,” in which it buys data from companies that maintain their own hardware and intellectual property rights.

“While that can be fruitful for everyone, what I worry about is becoming so dependent on some of these innovative solutions,” said Rick Spinrad, who led NOAA during the Biden administration.

“What happens when the founder [pivots]?”

The agency also needs more staffing to effectively manage the growing use of commercial data, he said.

“There’s a contradictory nature to what this administration is doing, advocating for private-sector delivery of data and then removing a third of the weather service.

Who’s going to manage these programs and make sure they’re effective?”

NOAA already lost access to a vital tool developed by Saildrone for improving hurricane forecasting and warning accuracy because it didn’t issue a request for contract proposals far enough in advance of hurricane season.

And there are risks that come with some of the technologies the agency is becoming reliant on when they are proprietary and unique to an individual company.

Agency dependence on one company for critical services or data is especially worrisome for Brad Colman, a private meteorologist who previously worked at NOAA.

“It’s a vulnerable position because you now have data that you have built your forecasting system around,” he said.

The company could demand more money, which could limit NOAA’s ability to invest elsewhere, or have the business challenges it faces affect the product it provides the government.

“There’s a contradictory nature to what this administration is doing, advocating for private-sector delivery of data and then removing a third of the weather service.”

RICK SPINRAD, NOAA ADMINISTRATOR DURING THE BIDEN ADMINISTRATION

Data ownership is another crucial concern.

Historically, NOAA has strived to make the commercial data it buys freely available to anyone who wants to use it for forecasting or research, said Mary Glackin, a former high-ranking official at NOAA who also worked at the Weather Company.

That’s best for public safety, she said.“There is no weather forecast that’s produced in this country that isn’t dependent on NOAA,” she said.

But free and open data licensing agreements can be costly for the government, and companies often want to retain some data to sell to private buyers.

In those situations, NOAA may buy data for its own purposes but withhold it from forecasters outside the agency for a set period.

The first Trump administration showed a willingness to choose this latter option.

A contract negotiated in 2020 with a company that had what many considered a superior hurricane forecasting model, for instance, constrained NOAA from publicly releasing the forecasts for five years, drawing criticism from hurricane specialists and private forecasters.

WindBorne’s Innovation

WindBorne’s AI-guided balloons stay aloft for months and collect vastly more data in the upper atmosphere than traditional weather balloons, which only fly for about two hours before popping and descending back to earth.

Called radiosondes, after the instruments they carry, traditional weather balloons cover just a fraction of the Earth, because it is logistically challenging to launch and receive data from them over the oceans and in remote areas.

WindBorne’s weather balloons collect thousands of data points, at different altitudes, across a horizontal expanse.

PHOTOGRAPH: WINDBORNE SYSTEMS

WindBorne’s balloons, in contrast, can collect and distribute data from remote regions.

That makes them more adaptive, and especially useful for monitoring atmospheric rivers that bring extreme precipitation to coastal regions, said Glackin.

“I’d like to see them in the suite of observing systems.”

The company deploys about 100 balloons from six launch sites globally, a fraction of the 92 launch sites operated by NOAA, but it aims to expand to launch up to 10,000 balloons globally over the next five years, Dean said.

Windborne’s data is less costly than radiosonde data “on a per observation or per station basis,” Curtis Marshall, the director of the Commercial Data Program for the NWS, wrote in an email.

And while its data is now free and open to the public, as the company expands, it wants to hold back some of the information it gathers for 48 hours so that it can sell it to private buyers, Dean said.

That data would no longer be useful to other forecasters.

Radiosondes’ Old School Technology is Difficult to Replace

Radiosondes collect one vertical profile—a line from ground level to the point where the balloon explodes—of data in the atmosphere, which is important for understanding climate change signals.

WindBorne’s balloons, in contrast, collect thousands of data points, at different altitudes, across a horizontal expanse.

Their path is somewhat ad hoc, determined by where the wind blows them, whereas radiosondes collect data in a line rising from a location that stays the same for each launch.

While WindBorne’s lack of a consistent path doesn’t matter for short-term weather forecasting, it could matter for understanding longer-term changes to the climate, which are currently based on decades of vertical profile data collected at the same spot, Glackin said.

WindBorne’s data would not be comparable with that historical record.

“We have a very cleaned-up climate record that allows us to talk about how the climate is changing,” she said.

“If all the radiosondes went away tomorrow, it would be hard to figure out what’s changed, and what to attribute to technology versus what really happened in the atmosphere.”

There are methods for transitioning to new instrumentation, Colman, the meteorologist who used to work at NOAA, said, but the NWS would need to proactively plan for that changeover to maintain a consistent data record.

The NWS isn’t moving to replace radiosondes—yet—but it is in the “early stages” of planning for a new suite of upper atmospheric observing systems that would provide data “substantially similar to the federal radiosonde network,” Marshall wrote.

The new observing systems would come from commercially operated balloons, drones, and aircraft, and “complement our federal balloon network.”

However, Austin Tindle, a cofounder of Sorcerer, a WindBorne competitor, said that officials within NOAA are increasingly asking him “what it could look like to be a true replacement to a radiosonde.”

“It’s been a vibe shift recently, coming up in conversation a lot,” he said.

WindBorne’s Dean declined to respond when asked if he’d been having similar conversations.

NOAA’s partnership with WindBorne “could be completely on the up and up [meaning an add-on rather than a replacement], but folks don’t have a lot of trust in the broader strategy for the NOAA weather enterprise, based on everything that’s happened,” said Di Liberto, citing the agency’s June 25 announcement that it was permanently ending—within just five days—a vital microwave satellite program used for forecasting hurricanes.

Dean at Windborne is none too eager to replace core NOAA functions.

“You’re better off augmenting than you are replacing traditional weather balloons, but we want to fill gaps wherever they form,” he said.

He’s not alone.

Tindle, whose solar-powered balloons are smaller and travel farther than WindBorne’s, said that Sorcerer “was never intended to be a replacement” for radiosondes, but to cover places in the world with no traditional balloon launches.

One reason for private weather monitoring companies’ caution about how much service they provide government lies in the directive that federal agencies have to serve the public, which is sometimes mismatched with business interests.

A Sofar solar-powered, satellite-connected buoy for measuring ocean-atmospheric dynamics is readied for deployment in advance of Hurricane Ian in 2022.

Sofar collaborated with NOAA to enhance hurricane forecasting in a project that was discontinued this year by budget cuts.

PHOTOGRAPH: US NAVAL RESEARCH LABORATORY SCIENTIFIC DEVELOPMENT SQUADRON VXS-1

Sofar collaborated with NOAA to enhance hurricane forecasting in a project that was discontinued this year by budget cuts.

PHOTOGRAPH: US NAVAL RESEARCH LABORATORY SCIENTIFIC DEVELOPMENT SQUADRON VXS-1

One of Sofar’s thousands of solar-powered, satellite-connected buoys that are deployed in five oceans around the world to capture real-time data on waves, weather, and sea surface temperature.

PHOTOGRAPH: SOFAR

PHOTOGRAPH: SOFAR

“The mandate of the government is not ours,” said Tim Janssen, a cofounder of Sofar, which has created a network of buoys that deploy from vessels and aircraft with sensors to monitor ocean conditions.

“It would be impossible for us to spend millions of dollars to do something just for societal benefit, [when] there isn’t a direct business case.”

Sofar provides shipping companies with forecasts to help them plan the safest and most fuel-efficient routes and partners with the US Navy, NOAA, and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

“The biggest concern for us over the last months has been the [lack of] awareness around the importance of those partnerships,” Janssen said, noting an increasing attitude of, “Let’s just rip it out and industry will take care of it.

That is a nonsensical idea.”

But the NWS may find itself backed into a corner, with limited options to gather, analyze, and distribute critical weather information.

“If I were NOAA, I’d be looking for a cost-benefit analysis on [WindBorne], although the politics are outpacing everything else and now your back’s up against the wall,” said Glackin.

“But I don’t think they can dance into the secretary’s office and say, here’s the answer to all our problems.”

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : For-profit companies can't easily replace NOAA's weather ... / The destruction of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric ...

Tuesday, August 12, 2025

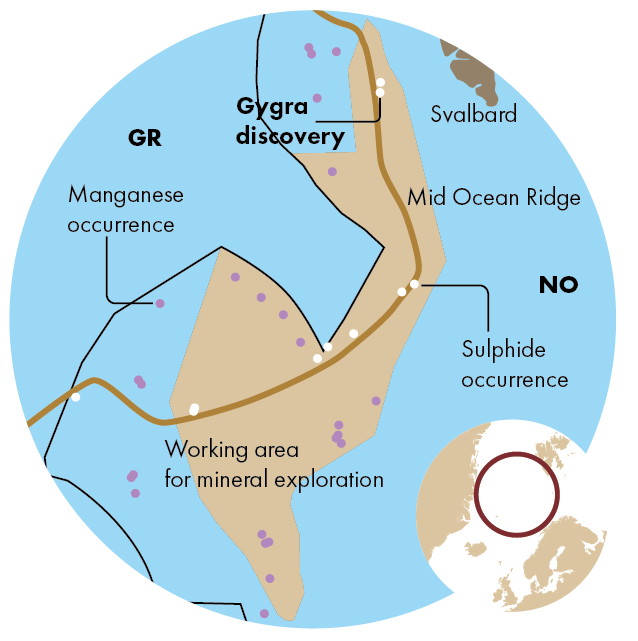

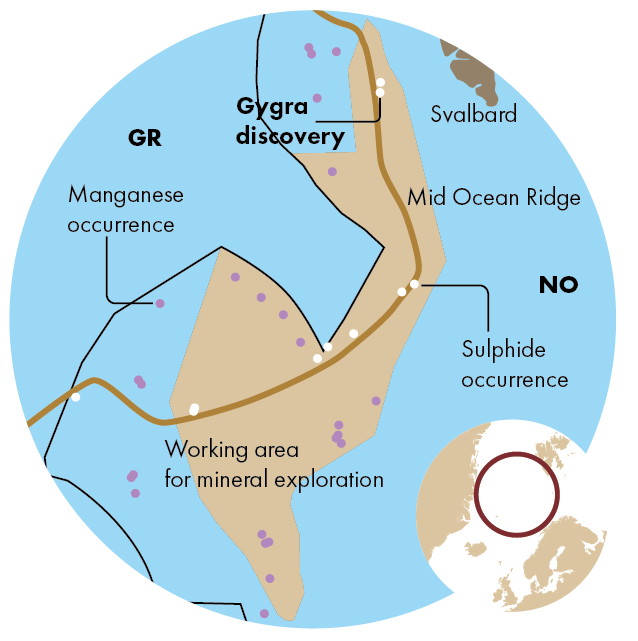

Despite putting the brakes on seabed mineral licensing, the Norwegian government continues to spend ever-increasing amounts on seabed mapping

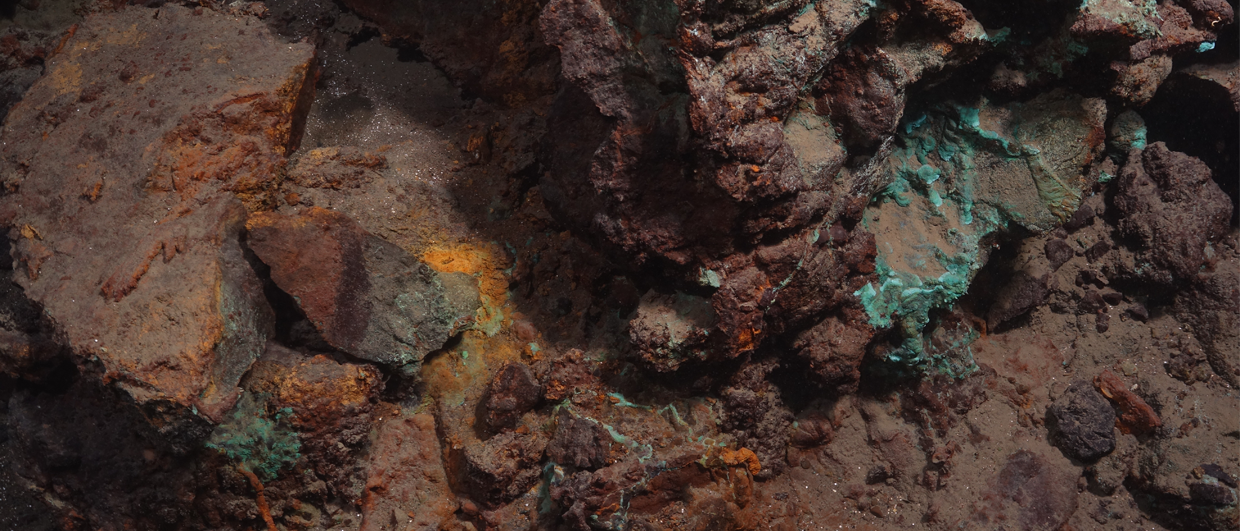

Gygra was first observed in December 2024.

The green colour indicate the presence of copper-bearing minerals.

Photography: Centre for Deep Sea Research, University of Bergen.

From GeoExPro by Ronny Setså

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate received a significant increase in funding in the 2025 state budget to continue mapping the deep sea

“We have been busy,” confirmed Hilde Braut, Deputy Director for New Industries at the Norwegian Offshore Directorate (NOD), when she gave a lecture at the Deep Sea Minerals 2025 conference in Bergen.

Braut pointed out that the directorate, in collaboration with the universities of Bergen and Tromsø, conducted three expeditions in 2024, and so far in 2025, they have completed two more.

When so much mapping is carried out, it is no surprise to see that the odd discovery is made as well.

During the latest expedition in March, a new sulphide deposit was confirmed and sampled.

“We have been busy,” confirmed Hilde Braut, Deputy Director for New Industries at the Norwegian Offshore Directorate (NOD), when she gave a lecture at the Deep Sea Minerals 2025 conference in Bergen.

Braut pointed out that the directorate, in collaboration with the universities of Bergen and Tromsø, conducted three expeditions in 2024, and so far in 2025, they have completed two more.

When so much mapping is carried out, it is no surprise to see that the odd discovery is made as well.

During the latest expedition in March, a new sulphide deposit was confirmed and sampled.

The deposit, which is named Gygra, is located on the Knipovich Ridge about a kilometer southeast of Jøtul, an active hydrothermal spring that was discovered in 2022.

A total of 53 samples were collected using the Ægir 6000 submersible’s grapple arm.

A key mineral

Braut said that the samples have so far been analyzed using a measuring instrument (handheld XRF) on board the ship.

The preliminary results appear to be encouraging from an exploration and resource perspective.

“The analyses indicate that the material has a copper content of between 2 and 30 %, with an average of 5 %,” said Braut.

She pointed out that the presence of the mineral atacamite is a confirmation of the high copper content in the deposit.

“The analyses indicate that the material has a copper content of between 2 and 30 %, with an average of 5 %,” said Braut.

She pointed out that the presence of the mineral atacamite is a confirmation of the high copper content in the deposit.

The same mineral was also detected at the Grøntua sulphide deposit on the Mohns Ridge.

Grøntua was found last year.

Braut was not the only speaker to highlight atacamite at the conference in Bergen.

Braut was not the only speaker to highlight atacamite at the conference in Bergen.

A research team at the University of Southampton has, in recent years, conducted research at the Semenov sulphide fields along the mid-ocean ridge in the Atlantic Ocean.

Their research so far has shown that atacamite in the upper, weathered part of the sulphides at the seafloor is a good indicator of the presence of copper in deeper layers.

PROSPECTIVE, BUT REQUIRES MORE RESEARCH

Recent expeditions in the Norwegian Sea have clearly shown that the Norwegian part of the mid-ocean ridge is very prospective in terms of sulphide resources.

Their research so far has shown that atacamite in the upper, weathered part of the sulphides at the seafloor is a good indicator of the presence of copper in deeper layers.

PROSPECTIVE, BUT REQUIRES MORE RESEARCH

Recent expeditions in the Norwegian Sea have clearly shown that the Norwegian part of the mid-ocean ridge is very prospective in terms of sulphide resources.

The list of known deposits is growing steadily, and of the deposits that have been sampled, the metal contents are often higher than what we typically see in deposits that are mined on land.

However, it is still an open question whether any of them will be viable. Single samples taken from the seabed are not sufficient to establish a resource estimate.

However, it is still an open question whether any of them will be viable. Single samples taken from the seabed are not sufficient to establish a resource estimate.

Drill cores are also needed to provide a sufficient statistical basis for the ore bodies in three dimensions.

Sunday, August 10, 2025

The final frontier of the deep sea

After a first expedition rich in discoveries in 2017, IFREMER (French Research Institute for the Exploitation of the Sea) and its mission leader, Ewan Pelleter, will lead a deep-sea exploration mission in the North Atlantic aboard the Pourquoi Pas.

The goal is to better understand the little-known world of the abyss, where underwater volcanic activity allows for the development of exceptional life forms as well as the production of extremely rare minerals that interest many industrial players and powers around the world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)