The Endurance in full sail, in the ice. The photo was taken when the crew felt they had a good chance of freeing the trapped Endurance from the sea ice of the Weddell Sea, so they put the sails up. This and other attempts failed, and, realizing the ship wasn’t moving, photographer Frank Hurley went onto the ice to take this photograph. Jan. 25, 1915.

From WSJ by J.S. Marcus

In the photography world’s equivalent of an IMAX event, devotees are about to get a hyperdetailed view of one of exploration’s great survival stories.

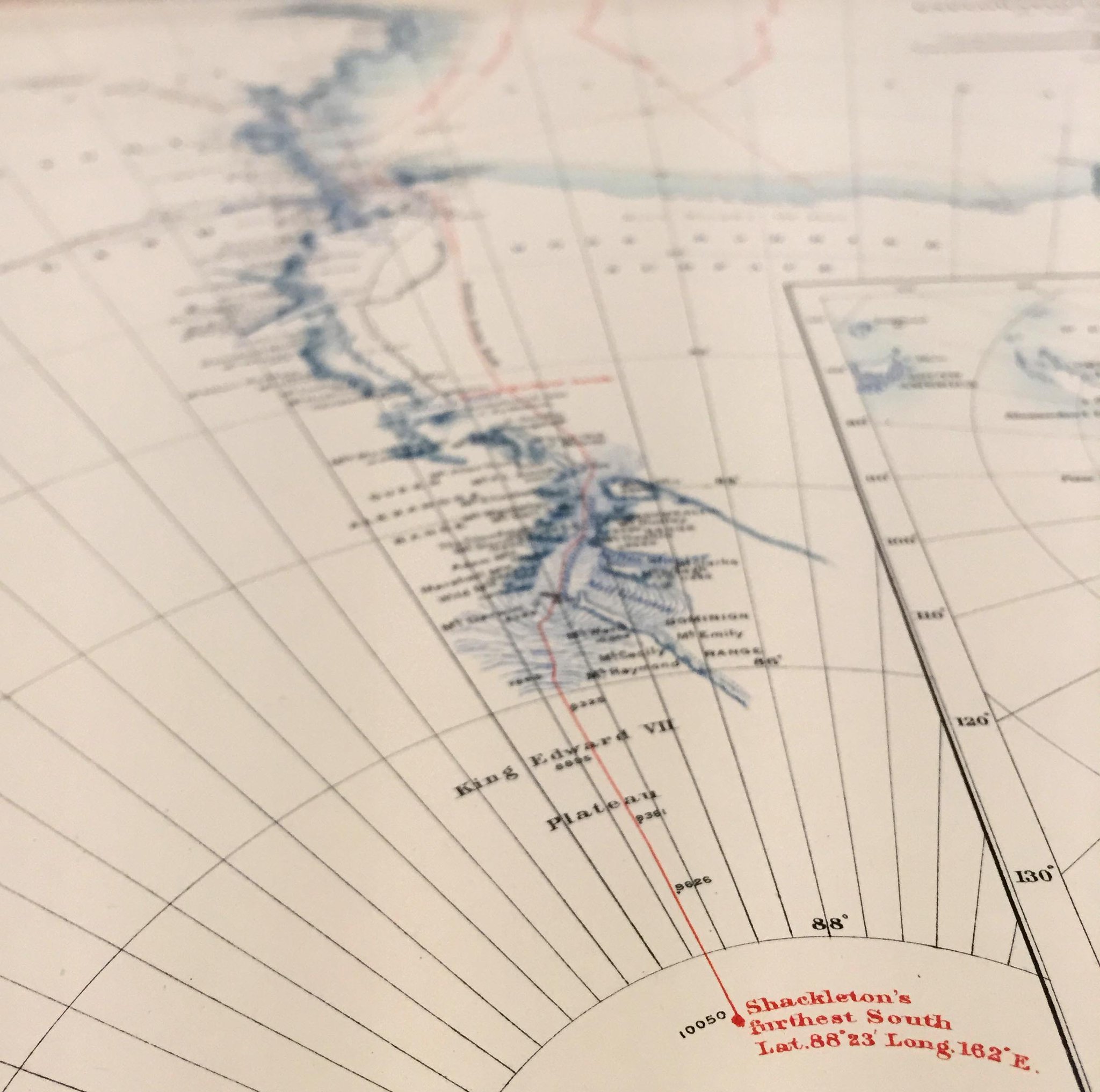

Sir Ernest Shackleton and his crew took bitter defeat and turned it into heroic survival.

Early this century, members of the imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition watched as their ship, the Endurance was crushed by the frozen sea.

They were left with no radio and no hope of rescue.

For more than a year, they drifted on packed ice, surviving on seal, penguin, and eventually dog meat, while battling freezing temperatures and mind-numbing boredom.

When Shackleton, along with all 28 members of the expedition, emerged at Stromness whaling station in May, 1916, almost two years after their departure, the world was shocked.

The ship became icebound, finally sinking on Nov. 21, 1915, and stranding the ship’s 28 men.

'The Long, Long Night' | The Endurance is lit by photographer Frank Hurley’s flares, Aug. 1, 1915. At right, the original glass plate negative; on left, the digitized image. The clarity of the new prints, made by digitally scanning the original negatives, means the photographs will have greater resolution than ever before, says Alasdair Macleod, head of collections at the Royal Geographical Society,

While most of the crew, including the expedition’s official photographer, Frank Hurley, waited on uninhabited Elephant Island off the Antarctic coast, Shackleton and a few of his men made an 800-mile sea voyage in a lifeboat, eventually reaching the South Atlantic’s South Georgia Island.

They climbed glacier-topped mountains to reach a whaling station, where Shackleton arranged a rescue of the rest of his crew.

The Endurance’s entire crew survived, and Hurley’s photos are a haunting visual account of the ordeal.

'The Night Watchman Returns'

Beginning Saturday, London’s Royal Geographical Society, the main repository of Frank Hurley’s glass-plate and Kodak negatives of the journey, will honor the centenary of the Endurance’s sinking with the debut of digital versions of the photos, along with several objects that survived the voyage.

'Mt. Page and the Allardyce Range from Mt. Duse, South Georgia' |

'I gave him a hand to lug a whole plate camera & 40 lbs of gear

& accoutrements & by gum we had some lovely places to go up,

like a fly crawling up a wall ... he did get some beauties though from

the top,’ explorer Lionel Greenstreet wrote in a letter, Nov. 17,

1914

The itinerary hasn’t been announced.

'On the Drifting Flow “Ocean” Camp' (Oct. 30, 1915) | Shackleton stands by his tent shoulder-to-shoulder with his second in command Wild. Scientists and officers stand in midground and the crew at the back.

The London version of the show includes 97 Hurley photographs along with objects such as a Union Jack presented to Shackleton by King George V and meant to be flown at the South Pole.

The flag made its way back with the rescued crew.

Expedition members take a hot drink.

Hurley’s images themselves may be familiar, says Alasdair Macleod, head of collections at the Royal Geographical Society, but the clarity of the new prints made by digitally scanning the original negatives means the photographs will have “greater resolution than ever before.”

The file sizes of previous digital versions were about 4 megabytes each, while the newly scanned versions are about 1.5 gigabytes.

Photographer Frank Hurley with his Vest Pocket Kodak outside the hut.

The exhibit has developed the new digital scans into oversize prints, some more than 8 feet long. “Hurley always intended his images to be several feet across,” says Mr. Macleod.

An exhibition is shedding new light on the Antarctic expedition by British explorer Ernest Shackleton a hundred years ago.His ship was trapped in ice for months before he led his men to safety.

In addition to revealing previously unseen details of the images—like the names of the books the crew was reading—the new digital versions will be able to show “how the ice looked” at the time, he adds.

That could help climate scientists track changes to the continent’s ice cover.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment