From National Geographic by Sarah Gibbens

Environmentalists are chasing industrial fishers that may be threatening fisheries in developing waters and marine protected areas.

Ocean conservationists from watchdog group Oceana are hunting for illegal fishing activity, and one new method they are exploring for catching offenders is satellite data.

The data comes from a monitoring network called the Automatic Identification System, or AIS.

AIS was established so large ships could broadcast their locations and avoid collisions.

In a new report from Oceana, researchers detail examples of how they used AIS collected by conservation group Global Fishing Watch to track four fishing vessels that were "going dark," or trying to avoid detection.

They say the case studies are examples of how AIS data can be used to track illegal fishing activities in the future.

"Illegal fishing is a global problem that's threatening the sustainability of our world's fisheries," says Lacey Malarky, an analyst for Oceana and co-author on the report.

"It's a big deal for countries that rely on seafood for their livelihoods. [Illegal fishing] really impacts local communities that need oceans to survive."

A report released by Greenpeace last year estimated that illegal fishing in West Africa alone costs the region more than $2 billion annually.

Illegal fishing also threatens a number of marine protected areas that are set up to restrict fishing activities in order to keep marine animal populations healthy, but which may be difficult for many countries to patrol.

Tracking dark ships

In the specific cases Malarky and her co-author Beth Lowell analyzed, ships were transmitting AIS signals for some of the time, and algorithms were then used to identify when the signal ceased for longer than 24 or 48 hours.

"It really is happening everywhere in every ocean and in a lot of countries' national waters," says Malarky.

"These four case studies are just the tip of the iceberg."

A Panamanian ship called the Tiuna was the first fishing boat they identified going dark.

In October 2014, the vessel was transmitting AIS data on the western boundary of the Galápagos Marine Reserve.

The region is one of the most biodiverse on the planet and hosts a number of lucrative fish.

The ship was dark for 15 days before it began transmitting signals again on the reserve's eastern border.

A Panamanian commercial fishing vessel seemed to disappear on the west side of the Galápagos Marine Reserve, reappearing after 15 days on the east side of the reserve.

Courtesy of Oceana

According to the data, the vessel turned off its AIS system before entering the reserve and turned on its system after exiting.

An Australian commercial fishing vessel appeared to disable its AIS near the Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve on 10 separate occasions over one year.

In 2014 and 2015, a Spanish fishing vessel called the Releixo went dark when leaving the port of Dakar in Senegal and entering Gambian waters.

The ship went dark at least 21 times during this period, each time for an average of 16 days.

A Spanish commercial fishing vessel appeared to repeatedly go dark when approaching The Gambia’s national waters over a one-and-a-half-year period.

The final case study highlighted in the report looked at a Spanish vessel called Egaluze that, over a period of seven months from 2012 to 2013, appeared to turn off its AIS system while operating in national waters of five different African countries.

The vessel also turned off its navigation monitoring system while on the high seas.

Another Spanish commercial fishing vessel appeared to turn off its AIS signal consistently over a seven-month period while operating in the national waters of at least five African countries and on the high seas.

"The regions we're highlighting are illegal fishing hotspots," says Malarky.

"Going dark is not necessarily illegal. It may indicate that they're doing something suspicious, but we can't prove they're doing anything illegal because we can't see what they're doing."

Evading detection by pirates, for example, is one reason a fishing vessel may need to disable its AIS detection system.

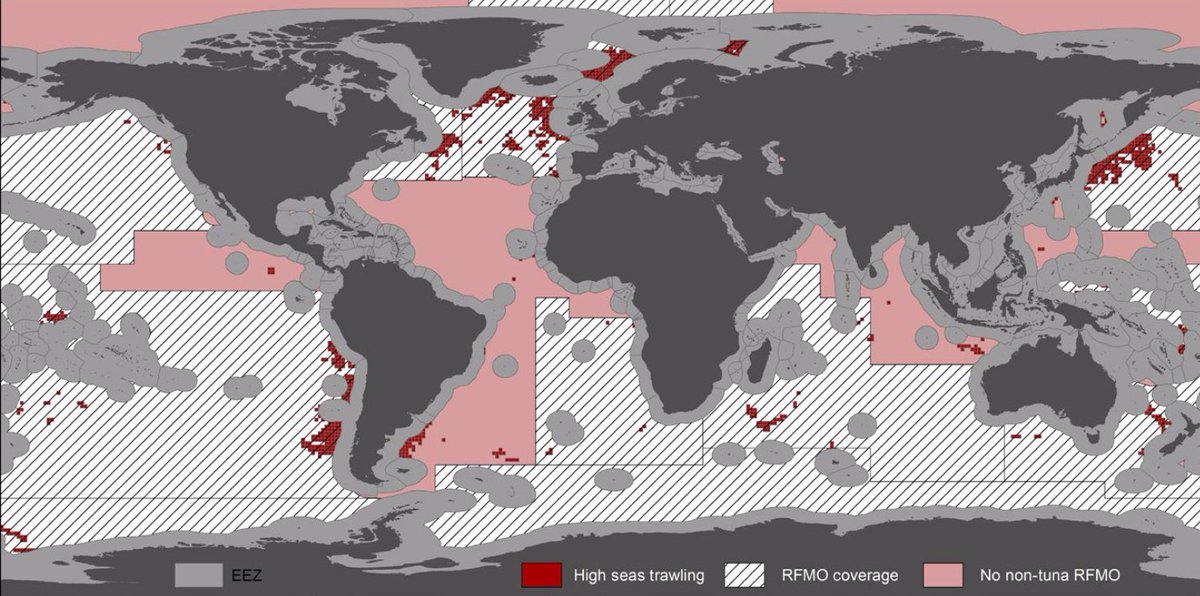

"It is a difficult task to discern between intentional disabling of the AIS, equipment malfunction, or issues with satellite coverage," says Juan Mayorga, a marine data scientist whose report last month also used Global Fishing Watch data to estimate that industrial fishing covers a third of the planet.

"Despite these limitations, we can—for the first time—use this data to investigate patterns of suspicious behavior and close-in on potentially illegal behavior. A vessel going dark now triggers a signal that tells us when and where to look," Mayorga adds.

Increasing transparency

The report made several recommendations to increase transparency around ships turning off AIS systems.

One is around vessel size.

The International Maritime Organization requires all passenger ships, tankers, and ships above a certain weight to transmit AIS, but the EU mandates the rule only for vessels longer than 15 meters. Individual governments can mandate how to what extent that requirement is enforced and conservationists say this is a major loophole.

"There really is no global standard," adds Malarky.

To track commercial fishing activity around the world, SkyTruth, a small nonprofit based in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, has recently launched Global Fishing Watch in partnership with Google and Oceana.

This prototype tool analyzes a satellite-collected feed of tracking data from ships' automatic identification systems—which vessels use to communicate their location to one another—to map movement over time and automatically determine which ships are engaged in fishing activity.

Each vessel is pinpointed on a map outlining fishing laws around the globe.

This map is publicly available on the Web, allowing anyone with an Internet connection to act as a watchdog and see when and where commercial fishing activity is occurring.

Her report also recommends vessels be required to state why they stop transmitting AIS, paired with stronger enforcement by local governments to punish—and thus deter—law-breaking activities.

In addition to protecting developing nations' fisheries, the report states enforcing AIS best practices plays an important role in helping reach the UN goal of protecting 10 percent of the ocean by 2020 (a goal we likely won't reach).

Links :

- Maritime Executive : Oceana: Fishing Vessels "Going Dark" Near Protected Waters

- VOA news : Fishing Boats Switch Off Trackers, Raise Suspicions of Illegal Fishing

- Wired : Ships keep vanishing from trackers in protected waters, raising fears of illegal fishing

- NPR : Fishing Boats 'Going Dark' Raise Suspicion Of Illegal Catches, Report Says

- GeoGarage blog : Fighting illegal fishing with Big Data / Global Fishing Watch lets you track 35000 fishing boats ... / Google's global fishing watch is using 'manipulated data' / Eyes in the sky: Green groups are harnessing data from ... / How satellites and big data can help to save the oceans / How satellite technology is helping to fight illegal fishing / Google's global fishing watch is using 'manipulated data' / The plan to map illegal fishing from Space

Empowering high seas governance with satellite vessel tracking data

ReplyDelete