Russia is spending billions to assert control over a vital shipping route in the Arctic.

It's much faster than the traditional route, and with the hydrocarbon reserves that lie beneath it, the Northern Sea Route is a goldmine for global powers

From Financial Times by

As climate change opens northern shipping lanes, Moscow is spending billions to dominate the region

Just days before a major Arctic conference this month in St Petersburg, where president Vladimir Putin was to host four regional leaders under the banner “Arctic: Territory of Dialogue”, Russian warships were on manoeuvres in the frigid northern waters.

On the waves of the Barents Sea, a frigate from the Northern Fleet fired rockets to shoot down cruise missiles launched from one of its own anti-submarine warships.

It was a show of strength not missed by Mr Putin’s guests.

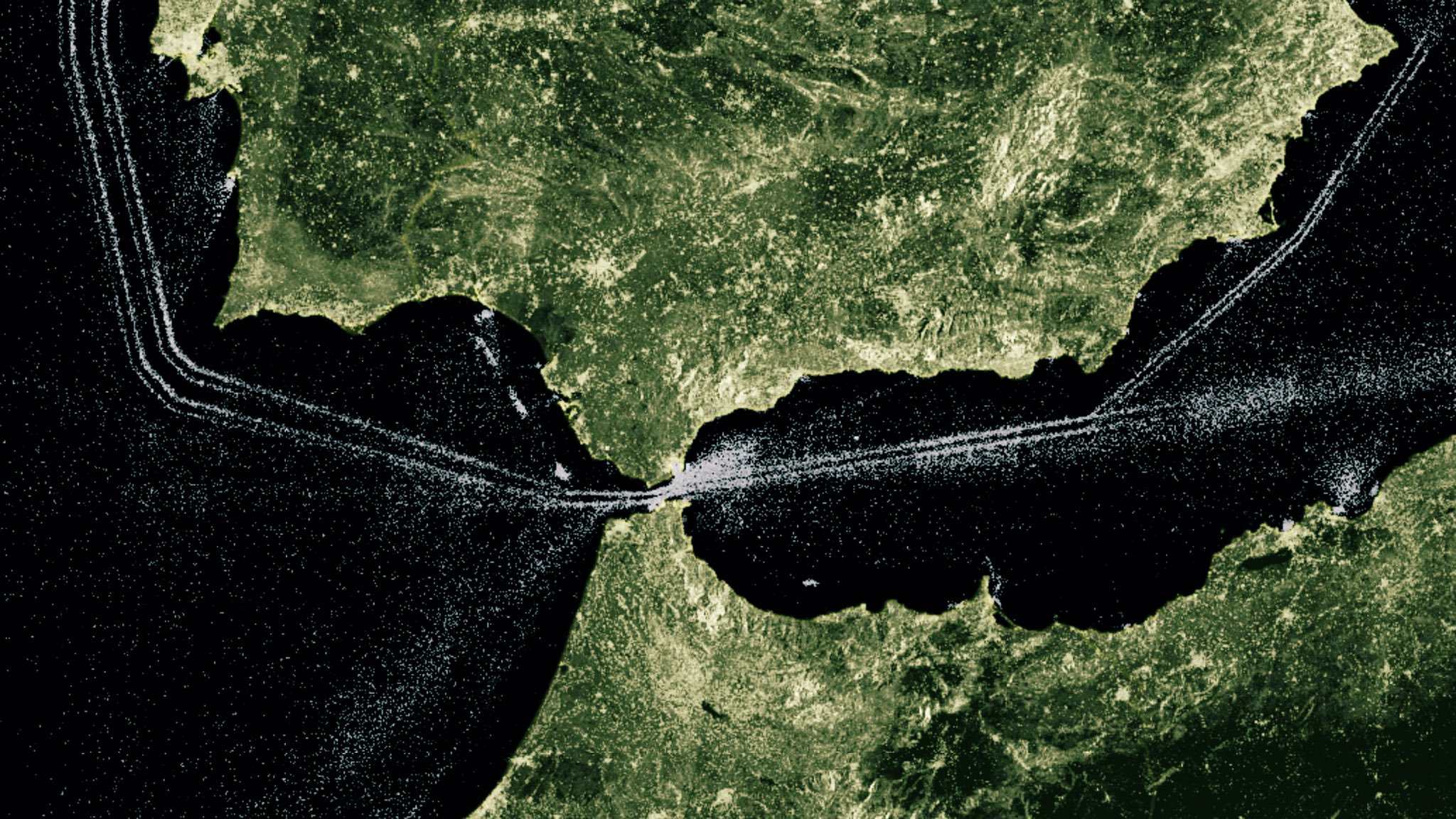

The Barents, whose waters lap Norway’s coast, marks the western boundary of the Northern Sea Route, a stretch of water encircling the North Pole that has for thousands of years remained mainly ice-bound, but whose rapid thaw has ushered in one of the world’s biggest emerging geopolitical flashpoints.

Fuelled by climate change that is rapidly shrinking the northern ice cap, the NSR has become an arena of growing competition.

Its potential as a preferential shipping route between Europe and Asia could change global trade flows.

The colossal hydrocarbon reserves that lie beneath it could upend energy markets.

And its growing militarisation has caught the attention of world powers.

Russia has an extensive sea bottom claim in the Arctic region.

The large hashed area reflects Russia's current extended continental shelf claim

While dozens of countries have begun staking claims to its riches, none has been as proactive as Russia in seeking to exploit the region, leaving others scrambling to keep pace.

One-tenth of all of Russia’s economic investments are currently in the Arctic region, Mr Putin said this month in St Petersburg.

Since 2013, Russia has spent billions of dollars on building or upgrading seven military bases on islands and peninsulas along the route, deploying advanced radar and missile defence systems — capable of hitting aircraft, missiles and ships — to sites where temperatures can fall below -50C.

It gives Moscow almost complete coverage of the entire coastline and adjacent waters.

The message is clear.

If you want to sail through the Arctic and travel to and from Asia faster, or have designs on the oil and gas assets beneath the sea, you will be under Russian oversight.

“The Americans think that only themselves can alter the music and make the rules,” Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, told the St Petersburg gathering.

“In terms of the NSR, this is our national transport artery.

That is obvious . . . It is like traffic rules.

If you go to another country and drive, you abide by their rules.” While traffic is light today, it is growing.

Experts estimate that during ice-free months, eastward shipment from Europe to China through the NSR is estimated to be around 40 per cent faster than the same journey via the Suez Canal, lopping hundreds of thousands of dollars off fuel costs and potentially cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 52 per cent.

At the moment the Arctic Ocean has just three ice-free months a year but several estimates suggest that number will increase in coming years, boosting access and driving up traffic.

Boosting Northern Sea Route shipping is a big part of the Arctic development plan.

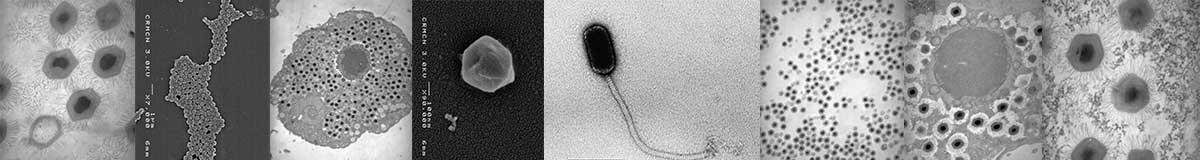

The 50 Let Pobedy nuclear-powered icebreaker, operated by Atomflot, smashing through the frozen waters of the Gulf of Ob In anticipation of a shipping boom, Russia has pushed through legislation to increase its control, including giving Rosatom, its state-owned nuclear power conglomerate, a monopoly over managing access to the NSR through icebreakers that can chaperone ships.

With a fifth of its land inside the Arctic Circle, Russia has gone in search of more territory, claiming that underwater ridges mean it should be granted another 1.2m square kilometres of the Arctic Ocean.

The UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf has recognised part of the neutral Arctic waters as a continuation of the Russian shelf.

As a result, the Mendeleev Rise and the Lomonosov Ridge may become Russian by the summer of 2020, says an official familiar with the talks.

Rivals are scrambling to catch up: This week the US announced it had ordered its first icebreaker for more than two decades, spending $746m on a ship to be ready in 2024.

“Against the backdrop of great power competition, the [ship] is key to our nation’s presence in the polar regions,” says Admiral Karl Schultz, commandant of the US Coast Guard, citing “increased commerce, tourism, research, and international activities in the Arctic”.

In 2007, Russian explorers planted a titanium white, blue and red tricolour flag on the seabed below the North Pole.

That act, the most audacious and theatrical part of a bid to claim the Pole, came almost 300 years after Russia’s Arctic exploration began.

Expeditions ordered by Peter the Great first mapped out an Arctic coastline of around 24,000km — roughly the same length as Russia’s entire land borders.

Russia built the world’s first icebreaker, the Yermak, 120 years ago.

In 1957, it built the first nuclear-powered version, the Lenin.

Its Arktika icebreaker was the first to reach the North Pole in 1977.

“Little has changed essentially in those years, both in the shape of the frame and the inside components,” says Sergei Frank, head of state-owned shipping company Sovcomflot.

During the cold war, the Soviet Union threw huge resources at the region.

The Northern Fleet was the largest in the Soviet Navy, and Arctic air bases provided refuelling points for nuclear-capable bombers.

Western powers settled for containment, with Nato forces patrolling the gaps between Greenland, Iceland and the UK in a bid to prevent Soviet submarines armed with ballistic missiles from passing into the Atlantic undetected.

But as the Soviet economy crumbled, the Arctic infrastructure steadily fell into disrepair.

Expensive to maintain and lacking a strategic rationale, Moscow slowly shifted focus.

Climate change and the growing power of Asian economies have changed that calculation.

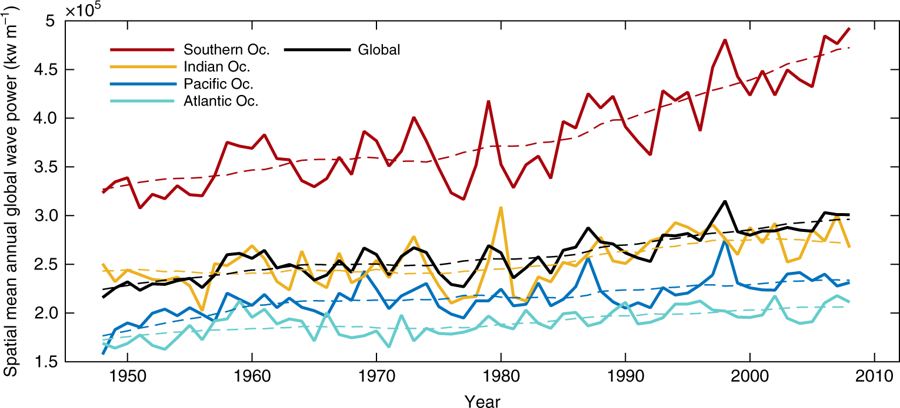

Arctic ice has shrunk by 12.8 per cent a decade on average since 1979, according to Nasa data, and last year’s September ice cover was 42 per cent lower than in 1980, turning a frozen, secure northern border into a hotbed of potential exploitation and conflict.

Last year Russia’s Northern Fleet conducted its largest military exercise for a decade.

“Russia simply doesn’t have another ocean,” the country’s natural resources minister, Dmitry Kobylkin, said last week.

“All projects implemented in the Arctic are our future horizons.” But where Moscow sees a security challenge, other countries see opportunity.

Last August, Danish shipping major Maersk ran a trial shipment along the NSR, when the Venta Maersk ferried electronics, minerals and 660 containers of frozen fish from Vladivostok to St Petersburg.

The first-ever NSR transit by a container ship, which Maersk says was a “one-off trial” to gain experience, was chaperoned by a Russian icebreaker along most of the country’s north-eastern coastline.

Ships from 20 different countries plied the waters of the NSR last year, carrying a total of 20m tonnes of cargo.

While paltry in comparison to traditional global shipping routes, it is double the amount in 2017, and Russia expects that figure to quadruple by 2025.

“This is a realistic, well-calculated and concrete task,” Mr Putin said this month.

“We need to make the Northern Sea Route safe and commercially feasible.” Rosatom says the cargo target could be beaten, provided it receives new icebreakers on time.

“Life doesn’t end there,” says Alexei Likhachev, Rosatom’s head.

“We are aiming for 92.6m tonnes in transit by 2024 rather than 80m tonnes.

And by 2030, we hope to add a significant part of international transit to that.” China’s increased interest in the Arctic, and its developing friendship with Russia, will be critical in hitting that target.

In this photo taken on April 3, 2019, a Russian solder stands guard near a Pansyr-S1 air defense system on the Kotelny Island, part of the New Siberian Islands archipelago located between the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea, Russia.

Beijing has observer status on the Arctic Council, a body designed to manage regional co-operation; has a research station on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard; and is the biggest foreign shareholder in Russia’s Arctic liquefied natural gas projects, which will rely on NSR shipments for exports.

Last year, China published an Arctic policy paper that explicitly linked the NSR to its ambitious Belt and Road strategy of developing pathways for both trade and influence, dubbing it the “Polar Silk Road”.

“I remember that just two decades ago people were saying [the NSR] was impossible,” says a foreign ambassador in Moscow.

“But when I heard the term Polar Silk Road and realised the Chinese were interested, I knew it was serious.” Shipping companies from South Korea, where many of Russia’s cargo tankers are built, have also conducted pilot voyages since 2013.

“South Korea and other Asian countries consider the NSR the shortest shipping route linking Asia and Europe and one of great commercial potential,” says Park Heung Kyeong, ambassador for Arctic affairs for Seoul’s foreign ministry.

Yet turning potential into profit will not be easy.

Ships often require an escort from an icebreaker as a precaution even when the NSR is ice-free.

“This is a very difficult and technologically intense task because we exist in a very competitive environment,” says Maxim Akimov, Russia’s deputy prime minister.

Russia has the world’s only fleet of nuclear icebreakers.

All but one of its four-strong fleet will be replaced over the next decade at an estimated cost of between $500m and $1.5bn each.

By 2035, its Arctic fleet will include least 13 icebreakers, including nine nuclear powered vessels, according to Mr Putin.

Moscow also needs to expand and develop ports at both ends of the route — Murmansk close to the Norwegian border and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Kamchatka Peninsula near Japan — and has invited foreign companies to invest in the projects.

“We are convinced that there is demand for the NSR and plan to implement the project with the help of broad international partnerships,” says Rosatom.

At the St Petersburg conference, the most commonly used word among foreign officials was “co-operation”.

Although senior representatives from Canada and the US were conspicuous by their absence, presidents, prime ministers and top diplomats from European Arctic powers were at pains to make clear they wanted to work with Moscow.

Indeed they might.

Russia’s rapid and determined push to assert its control over the NSR has unnerved many of its Arctic neighbours, which are now seeking to collaborate with the Kremlin.

Complicating the issue is the soured relationship between Russia and the west, due to Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, the attempted assassination of a former spy in the UK last year and efforts to meddle in foreign elections.

Those factors, and the resulting sanctions levied by western countries, mean some governments are tentative about working closely with Moscow on commercial or security issues, and have instead focused on areas such as environmental protection and safety.

Without action to mitigate human sources of greenhouse gas emissions, the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free during the summer months before 2050, and possibly within the next decade or two, a UK parliament defence committee report warned last year.

“We want to have good relations with Russia, but at the same time we do not give up on the things which we believe in and things which we look at differently,” Sweden’s prime minister Stefan Löfven told Mr Putin on stage in St Petersburg.

Marie-Anne Coninsx, the EU’s ambassador-at-large for the Arctic, denies that Brussels had been slow to react to the region’s potential.

“We have for many years been engaged with the Arctic,” she says.

“We are co-operating well with Russia — co-operation not competition.” Brussels is working with Moscow on issues ranging from water waste management to the treatment of nuclear waste in the region, she adds.

“The EU’s member states have the biggest merchant fleet in the world,” Ms Coninsx says.

“If there are new economic opportunities, they will be used.” But the west’s other response was illustrated last October, when Nato troops carrying assault rifles poured out of landing craft on to beaches in northern Norway.

Operation Trident Juncture was the military alliance’s largest war games since the cold war, and saw 50,000 troops, 10,000 vehicles and 250 aircraft from 31 countries participate in a four-week long exercise close to the country’s border with Russia.

Condemned by Moscow as aggressive posturing, analysts said it illustrated how seriously Nato took Russia’s ambitions in the frozen north, and its understanding that its troops needed experience of operating in the region.

Russia is “staking a claim and militarising the region”, UK defence secretary Gavin Williamson said last September as he announced the country’s new Arctic defence strategy.

“We must be ready to deal with all threats as they emerge.”

Around 800 Royal Marines troops are training in Norway this year, while four RAF Typhoons are patrolling in the skies above Iceland for the first time.

The US is expected to release a new Arctic strategy this summer, a document that the Pentagon has said will focus on how to “best defend US national interests and support security and stability in the Arctic”.

“Russia’s development of its Arctic areas . . . gets immense attention, and that creates both fair and unfair competition, which is pure politics,” says Konstantin Kosachev, chairman of the foreign affairs committee at Russia’s upper house of parliament.

That challenge of balancing defence and development is the biggest question facing Russia, says Chris Tooke, analyst at GPW, a political risk consultancy.

Moscow helped Arctic gas producer Novatek by relaxing a requirement that only Russian-registered vessels can traverse the NSR which would have dented its export potential.

But Mr Tooke believes such steps will be rare.

“On balance, I would expect security imperatives to trump commercial interests, and this tension and the need to develop infrastructure will probably slow progress in commercial exploitation in the medium term,” he says.

“But the potential is definitely there.”

Links :

_-_SLV_H99.220-4466.jpg)