From ERC

Dr Joaquim Alves Gaspar is a man of the sea.

After many years in the Portuguese Navy, he gave up plans to become an admiral in favour of pursuing a PhD in the History of Cartography.

This second career led him to receive an ERC Starting Grant, the first awarded in this budding discipline.

With his highly multidisciplinary team (he likes to say that, to work with him, one must be a mathematician fluent in Latin), and the experience obtained as a navigator and navigational instructor, Dr Gaspar hopes to understand how and when the first nautical charts were created.

The

MEDEA-CHART team is the best place in Portugal, and probably in the world, to study the history of nautical cartography, hoping that this work will provide the domain with its rightful recognition within world history.

What is your research project about?

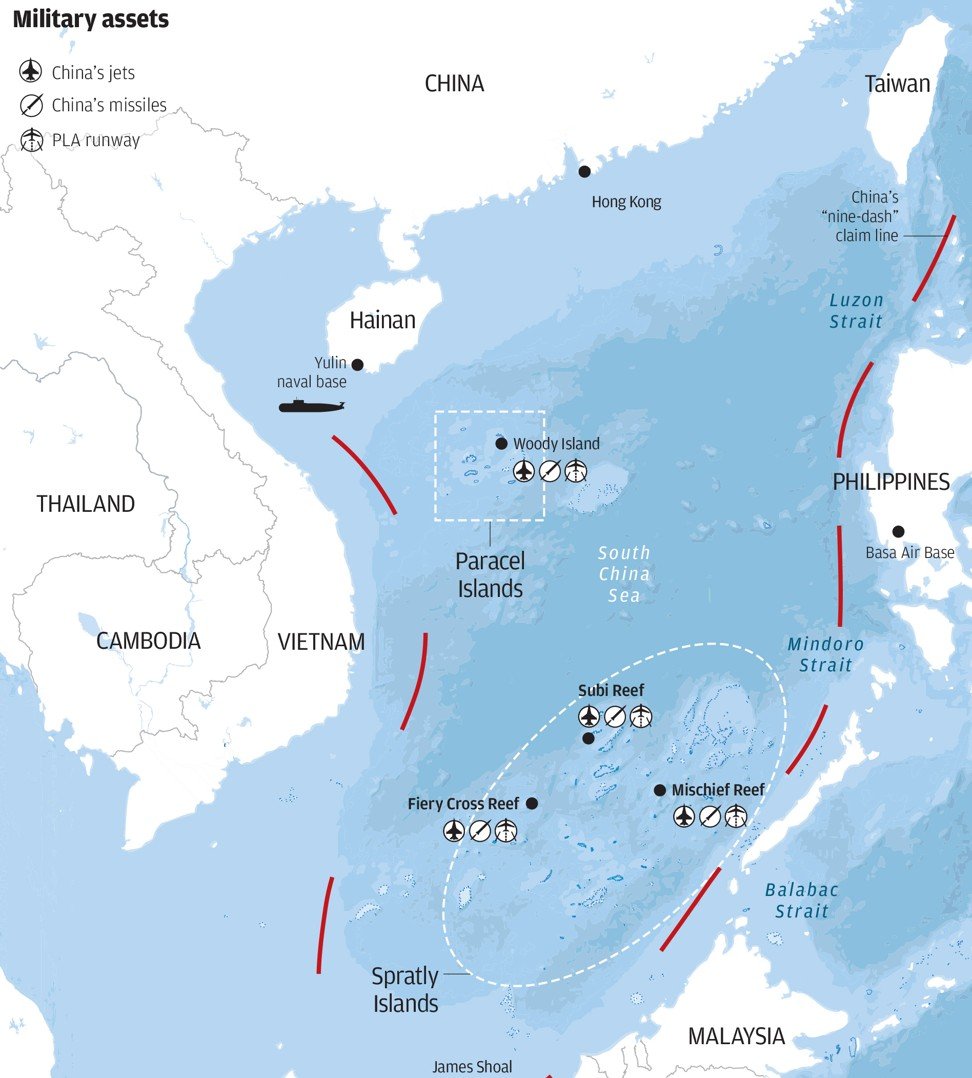

Our project is about the origin, the technical evolution and the use of nautical cartography in Europe.

This includes the medieval charts of the Mediterranean, what historians call portolan charts, and the early modern charts, first of the Atlantic and then of the whole world.

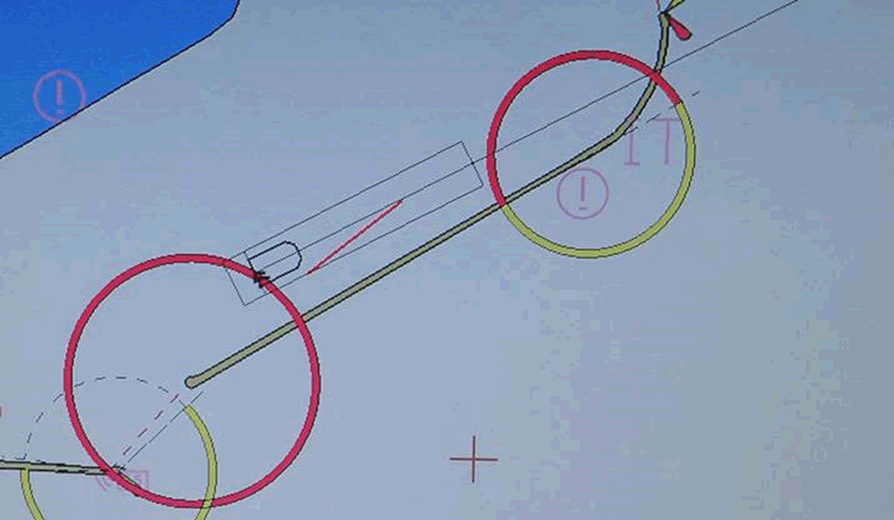

These charts, which preceded the Mercator projection (designed in 1569, and on which current navigation is based), didn't even consider the Earth as round!

In fact, although people of course knew about it, the constraints of navigational methods dictated that a flat-earth model be used until mid-18th century.

The MEDEA-CHART project is about studying these apparently naïve forms of cartographic representation, which were used for so much discovery and exploration.

What do you hope to achieve with your grant?

We hope to resolve some historiographical issues which have eluded scholars of cartography for a very long time.

For example, when and how were the first nautical charts constructed?

The earliest existent chart is the Carta Pisana (1275-1280).

But we suspect a long tradition before that, and we know nothing about its development.

Also, how were they updated with new geographical information?

These issues are particularly relevant for the medieval ones, but similar questions could be asked for the more recent, so-called, latitude charts of the Atlantic, which were developed by the Portuguese following the introduction of astronomical navigation.

This new model was based on the traditional charts of the Mediterranean but we don’t know exactly how it evolved from them.

These are two aspects we want to explore.

In addition, we'd like to understand how those charts were used to navigate.

We know almost nothing about that but we hope to by the end of this project.

We hope to resolve some historiographical issues which have eluded scholars of cartography for a very long time.

For example, when and how were the first nautical charts constructed?

How were they updated with new geographical information? (Carta Pisana – 1275-1280)

This research is quite unique, was the ERC support important for the discipline itself?

Absolutely, it was the very first ERC grant in the field of the History of Cartography.

My biggest wish is to include the History of Cartography, now a bit of a niche subject, into the History of Science.

I believe it belongs in this field because of its extraordinary relevance in the period of geographic discovery and maritime expansion.

Nautical charts weren't used only for navigation but also for the construction of the first coherent image of the whole world.

They were the most important source of geographical information during a period when the world was being discovered, explored and mapped by Europeans.

When we see those lavish atlases and maps of the world of the 16th and 17th century, we don’t realise that most of that information came from nautical charts, which were instruments for navigation not intended to depict the world.

Even more surprisingly, nautical charts were constructed not by scholars, but by artisans.

They were scientific tools made and used by illiterate workers, and this is in itself quite notable for the History of Science.

Finally, for the first time, we are using a multidisciplinary approach to study these maps, an approach which is extremely powerful and has already proven its potential.

Tell us more about this multidisciplinarity.

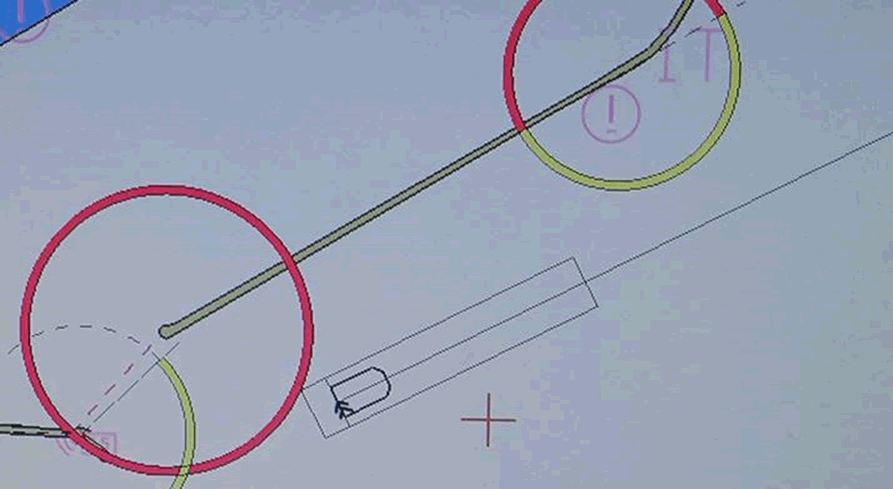

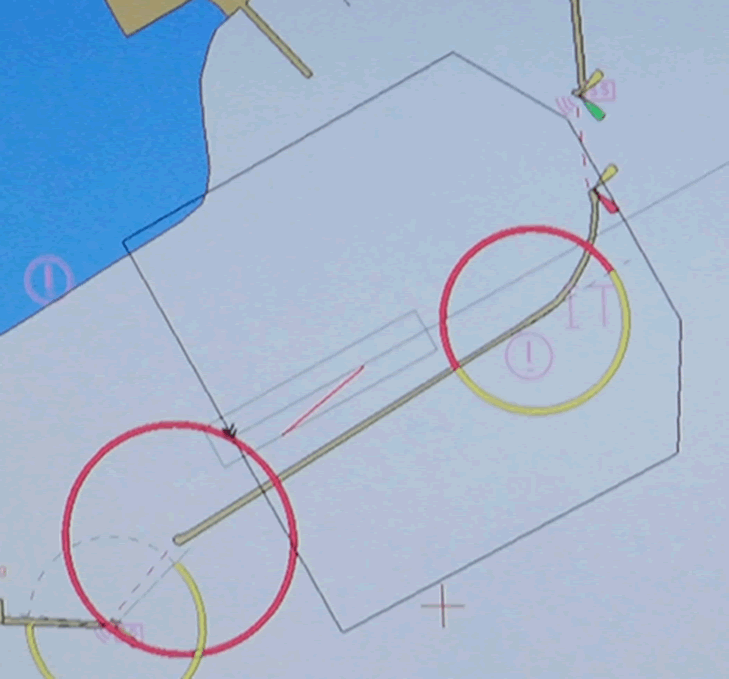

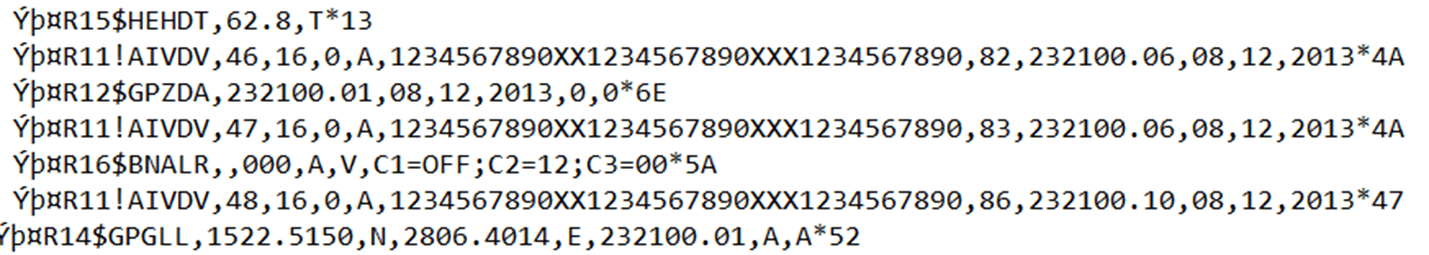

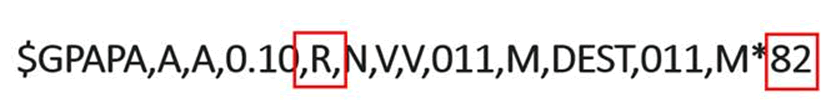

Essentially, not only do we study the sources using the traditional methods of historical research, but we also use geometrical analysis, mathematical modelling, radiocarbon dating and multispectral imaging technology.

Seven people work with me in the team, only one is a traditional historian.

We have three physicists, a philosopher, a computer science engineer, a neuroscientist and a navy officer.

One of them ia an American senior investigator and the world expert of the Piri Reis map (a well-known Turkish portolan chart from the 16th century).

We look at the charts themselves, lots of them.

But then written sources explaining how those charts came to be don't exist, so we try to understand the creation process by examining the charts themselves physically and mathematically, as well as interpreting the few textual sources where they are mentioned.

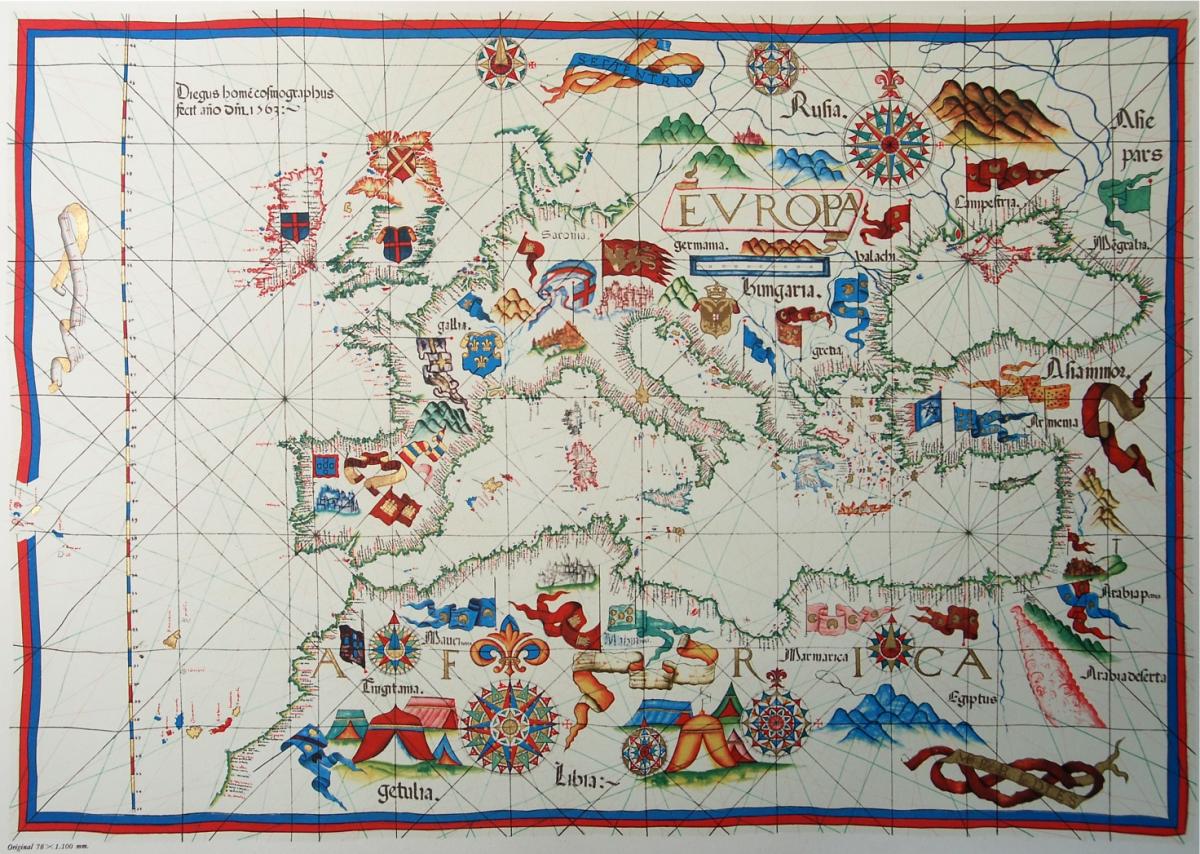

My biggest wish is to include the History of Cartography, now a bit of a niche subject, into the History of Science.

I believe it belongs in this field because of its extraordinary relevance in the period of geographic discovery and maritime expansion.

Nautical charts weren't used only for navigation but also for the construction of the first coherent image of the whole world.

(Anonymous Atlantic Chart – 1560)

How did you develop this passion for cartography?

I have been connected to the sea since I was a child.

I was always fascinated by maps and charts.

Charts and maps were part of my professional life in the navy but this particular interest in the History of Cartography began when I was sent to the Portuguese Navy Academy to teach cartography and hydrographic surveying.

Then I published two books on theoretical modern cartography.

That, at the time, was my real interest.

When the time came to decide about my career in the navy, about 15 years ago, I could have become an admiral but I realised that I had a bigger ambition.

I decided to start a PhD instead for which my background in the navy was ideal.

I was an expert in navigation, in hydrographical surveying and also in mathematical cartography, which are very powerful tools to approach the study of old nautical charts.

What 16th century Arabs thought Europe looked like on top of an actual map of Europe

How did your career in the navy develop?

My experience in the navy was very rich.

I spent several years at sea in different kinds of ships, as a desk officer when I was very young, as an operation officer, a navigator, and then as a commanding officer.

But I also had the opportunity to study a lot.

I have a Masters in Physical Oceanography which I obtained in the United States, I taught for many years in the Naval Academy and I served in the Hydrographic Institute as an oceanographer and an expert in navigation.

Most of what I know directly related to my research subject I learned from the navy.

I have been connected to the sea since I was a child.

I was always fascinated by maps and charts.

Charts and maps were part of my professional life in the navy.

At a point in my career, I could have become an admiral but I realised that I had a bigger ambition so I decided to start a PhD instead and study the history of cartography.

(Diogo Homem portolan – 1563).

What motivated you to apply for the ERC?

Simply put, to pass a message.

To make a significant contribution to the training of a new generation of historians of cartography.

Not traditional historians, but researchers prepared to apply a multidisciplinary approach, including physical and numerical methods.

As far as I know, there is no undergraduate degree in the History of Cartography, and the only research team in Europe solely dedicated to the subject is mine.

Being awarded an ERC grant was the only way to have the resources to pass this message.

Links :