Global sea level rise is accelerating incrementally over time rather than increasing at a steady rate, as previously thought, according to a new study based on 25 years of NASA and European satellite data.

If the rate of ocean rise continues to change at this pace, sea level will rise 26 inches (65 centimeters) by 2100--enough to cause significant problems for coastal cities.

From CNN by Brandon Miller

Sea level rise is happening now, and the rate at which it is rising is increasing every year, according to a study released Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers, led by University of Colorado-Boulder professor of aerospace engineering sciences Steve Nerem, used satellite data dating to 1993 to observe the levels of the world's oceans.

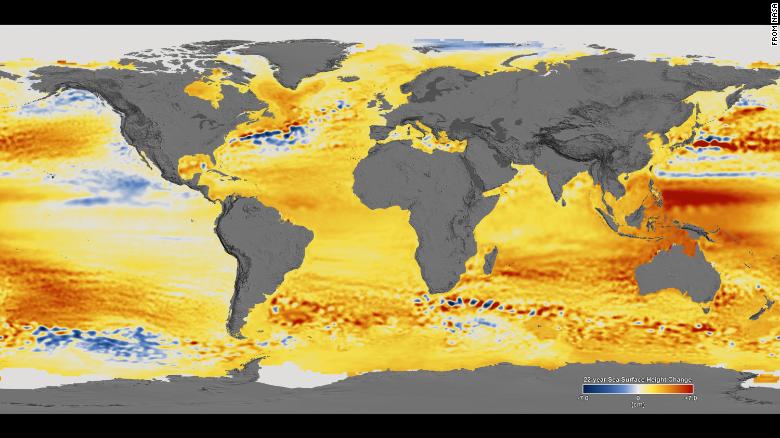

Changes in sea level observed between 1992 and 2014.

Orange/red colors represent higher sea levels, while blue colors show where sea levels are lower.

Using satellite data rather than tide-gauge data that is normally used to measure sea levels allows for more precise estimates of global sea level, since it provides measurements of the open ocean.

The team observed a total rise in the ocean of 7 centimeters (2.8 inches) in 25 years of data, which aligns with the generally accepted current rate of sea level rise of about 3 millimeters (0.1 inches) per year.

But that rate is not constant.

Continuous emissions of greenhouse gases are warming the Earth's atmosphere and oceans and melting its ice, causing the rate of sea level rise to increase.

"This acceleration, driven mainly by accelerated melting in Greenland and Antarctica, has the potential to double the total sea level rise by 2100 as compared to projections that assume a constant rate, to more than 60 centimeters instead of about 30," said Nerem, who is also a fellow with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Science.

That projection agrees perfectly with climate models used in the latest International Panel on Climate Change report, which show sea level rise to be between 52 and 98 centimeters by 2100 for a "business as usual" scenario (in which greenhouse emissions continue without reduction).

Therefore, scientists now have observed evidence validating climate model projections, as well as providing policy-makers with a "data-driven assessment of sea level change that does not depend on the climate models," Nerem said.

Sea level rise of 65 centimeters, or roughly 2 feet, would cause significant problems for coastal cities around the world.

Extreme water levels, such as high tides and surges from strong storms, would be made exponentially worse.

Consider the record set in Boston Harbor during January's "bomb cyclone" or the inundation regularly experienced in Miami during the King tides; these are occurring with sea levels that have risen about a foot in the past 100 years.

Now, researchers say we could add another 2 feet by the end of this century.

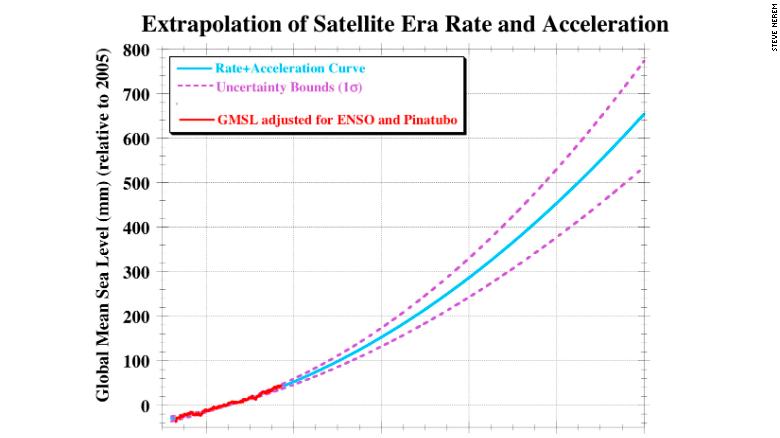

Nerem provided this chart showing sea level projections to 2100

using the newly calculated acceleration rate.

Nerem and his team took into account natural changes in sea level thanks to cycles such as El Niño/La Niña and even events such as the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which altered sea levels worldwide for several years.

The result is a "climate-change-driven" acceleration: the amount the sea levels are rising because of the warming caused by manmade global warming.

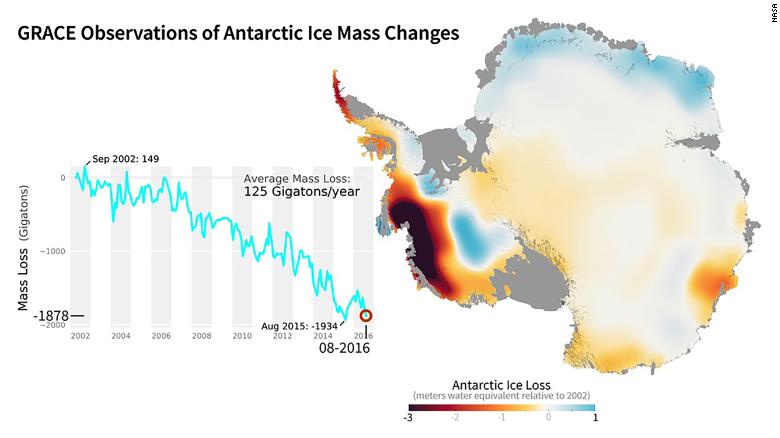

The researchers used data from other scientific missions such as GRACE, the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, to determine what was causing the rate to accelerate.

NASA's GRACE mission used satellites to measure changes in ice mass.

This image shows areas of Antarctica that gained or lost ice between 2002 and 2016.

Currently, over half of the observed rise is the result of "thermal expansion": As ocean water warms, it expands, and sea levels rise.

The rest of the rise is the result of melted ice in Greenland and Antarctica and mountain glaciers flowing into the oceans.

From the South Pole to Greenland, from Alaska’s glaciers to Svalbard, NASA’s Operation IceBridge covered the icy regions of our planet in 2017 with a record seven separate field campaigns.

The mission of IceBridge, NASA’s longest-running airborne science program monitoring polar ice, is to collect data on changing ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice, and maintain continuity of measurements between ICESat satellite missions.

Theirs is a troubling finding when considering the recent rapid ice loss in the ice sheets.

"Sixty-five centimeters is probably on the low end for 2100," Nerem said, "since it assumes the rate and acceleration we have seen over the last 25 years continues for the next 82 years."

"We are already seeing signs of ice sheet instability in Greenland and Antarctica, so if they experience rapid changes, then we would likely see more than 65 centimeters of sea level rise by 2100."

Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann, who was not involved with the study, said "it confirms what we have long feared: that the sooner-than-expected ice loss from the west Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets is leading to acceleration in sea level rise sooner than was projected."

Links :

- ArsTechnica : Yes, sea level rise really is accelerating

- The Guardian : Melting ice sheets are hastening sea level rise, satellite data confirms

- Inverse : 25 Years of Satellite Data Uncover Alarming Error in Sea Level Measurements

- EOS : Incorporating Physical Processes into Sea Level Projections

- EuroNews : Rising sea levels threat: a shrinking European coastline in 2100?

No comments:

Post a Comment