Saturday, November 1, 2025

Friday, October 31, 2025

Google partners Chile for Trans Pacific Humboldt cable

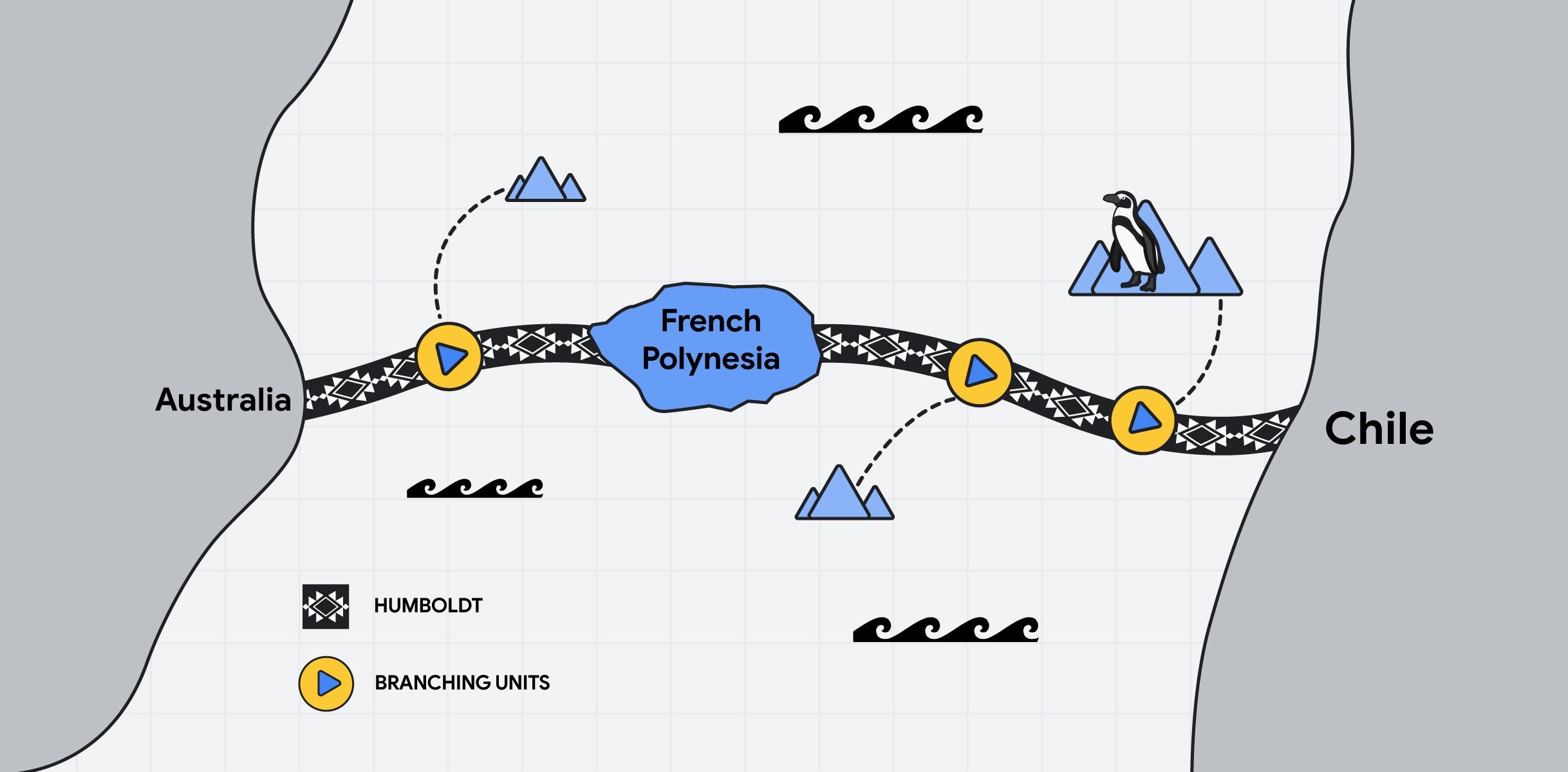

Cable will be 14000 km long between Australia and Chile

the first submarine cable that will link South America and Oceania

From Silicon by Tom Jowitt

Google and the government of Chile sign agreement for undersea cable connecting South America with Asia and Oceania

A stated-owned enterprise of the Chilean government (Desarrollo Pais) has signed a connectivity partnership agreement with Google.

According to a Google translation of the press release, both parties are creating a joint venture called Humboldt Connect, which will deploy an undersea fibre optic cable that “directly connect South America with Oceania.”

Humboldt Connect is set for deployment in 2025-2026. with commercial operation slated for 2027. It will be a 14,800-kilometre (9,200-mile) submarine data cable that will connect Chile’s coastal city of Valparaíso, with Sydney, Australia through French Polynesia.

Google and the government of Chile sign agreement for undersea cable connecting South America with Asia and Oceania

A stated-owned enterprise of the Chilean government (Desarrollo Pais) has signed a connectivity partnership agreement with Google.

According to a Google translation of the press release, both parties are creating a joint venture called Humboldt Connect, which will deploy an undersea fibre optic cable that “directly connect South America with Oceania.”

Humboldt Connect is set for deployment in 2025-2026. with commercial operation slated for 2027. It will be a 14,800-kilometre (9,200-mile) submarine data cable that will connect Chile’s coastal city of Valparaíso, with Sydney, Australia through French Polynesia.

Humboldt Connect

“This project, which will connect the Valparaíso Region with Australia via more than 14,000 kilometers of cable, represents a concrete expression of how we understand Chile’s place in the 21st century: as an open, reliable country fully committed to active international integration, with a vocation to be the bridge between South America, Asia-Pacific, and Oceania,” Chile’s Foreign Minister Alberto van Klaveren stated.

“This infrastructure has the potential to benefit neighbouring countries such as Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, and others, facilitating their access to more diversified, secure, and efficient digital routes,” added van Klaveren, adding that “we reaffirm our commitment to being a regional meeting and coordination point, promoting digital integration that is inclusive, sustainable, and oriented toward shared development.”

Desarrollo País and Google will each hold a 50-50 percent holding in the joint venture.

The Humboldt project has been a long time coming, having first been proposed back in 2016.

Between 2019 and 2020, economic, technical, and geopolitical feasibility studies were carried out, and in 2021, Chile’s Country Development Agency assumed project management and launched an international call for tender (RFP) in 2022.

It signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Google in 2023, which laid the foundation for the partnership.

Finally, in 2024, the seabed survey was completed, allowing the final route to be defined.

It should be remembered that Chile is home to one of Google’s largest data centres in Latin America.

Subsea cables

Although Google did not disclose its total investment, the Associated Press reported that Patricio Rey, general manager of local partner Desarrollo País, estimated the cable project’s value at $300 million to $550 million, with Chile contributing $25 million.

And Alphabet’s Google has invested heavily in subsea cables over the years.

This includes the ‘Dunant’ cable (named after Red Cross founder Henry Dunant) that runs from Virginia Beach in the United States to a landing station in the French west coast.

In 2024 Google confirmed it will spend $1 billion with two new subsea cablesconnecting the US and Japan, and a number of Pacific Island nations.

Thursday, October 30, 2025

Melissa is a beast among a string of monster Atlantic storms. Scientists explain

From AP by Seth Borenstein

Hurricane Melissa, which struck Jamaica with record-tying 185 mph winds Tuesday, was a beast that stood out as extreme even in a record number of monster storms spawned over the last decade in a superheated Atlantic Ocean.

Melissa somehow shook off at least three different meteorological conditions that normally weaken major hurricanes and was still gaining power as it hit, scientists said, a bit amazed.

And while more storms these days are undergoing rapid intensification — gaining 35 mph in wind speed over 24 hours — Melissa did a lot more than that.

It achieved what’s called extreme rapid intensification — gaining at least 58 mph over 24 hours.

In fact, Melissa turbocharged by about 70 mph during a 24-hour period last week, and had an unusual second round of rapid intensification that spun it up to 175 mph, scientists said.

“It’s been a remarkable, just a beast of a storm,” Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach said.

Melissa is a Category 5 storm with sustained wind speeds of 185 mph (295 kph).

It was expected to slice diagonally across the island, entering near St. Elizabeth parish in the south and exiting around St. Ann parish in the north.

The US Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters flew straight through Category 5 Hurricane Melissa, capturing an incredible view from inside the storm’s eye. pic.twitter.com/bq6bY3PqPz

— Nature is Amazing ☘️ (@AMAZlNGNATURE) October 28, 2025

The US Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters flew straight through Category 5 Hurricane Melissa, capturing an incredible view from inside the storm’s eye.

Melissa ties records

When Melissa came ashore it tied strength records for Atlantic hurricanes making landfall, both in wind speed and barometric pressure, which is a key measurement that meteorologists use, said Klotzbach and University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy.

The pressure measurement tied the deadly 1935 Labor Day storm in Florida, while the 185 mph wind speed equaled marks set that year and during 2019’s Hurricane Dorian.

Hurricane Allen reached 190 mph winds in 1980, but not at landfall.

Usually when major hurricanes brew they get so strong that the wind twirling in the center of the storm gets so intense and warm in places that the eyewall needs to grow, so a small one collapses and a bigger one forms.

That’s called an eyewall replacement cycle, McNoldy said, and it usually weakens the storm at least temporarily.

When Melissa came ashore it tied strength records for Atlantic hurricanes making landfall, both in wind speed and barometric pressure, which is a key measurement that meteorologists use, said Klotzbach and University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy.

The pressure measurement tied the deadly 1935 Labor Day storm in Florida, while the 185 mph wind speed equaled marks set that year and during 2019’s Hurricane Dorian.

Hurricane Allen reached 190 mph winds in 1980, but not at landfall.

Usually when major hurricanes brew they get so strong that the wind twirling in the center of the storm gets so intense and warm in places that the eyewall needs to grow, so a small one collapses and a bigger one forms.

That’s called an eyewall replacement cycle, McNoldy said, and it usually weakens the storm at least temporarily.

Des images satellites du coeur de l'ouragan Melissa révèlent une poignée de formations tourbillonnantes qui s'agglutinent dans son oeil parfaitement symétrique. @washingtonpost pic.twitter.com/hLB1BbJQHd

— L'important (@Limportant_fr) October 31, 2025

Melissa showed some signs of being ready to do this, but it never did, McNoldy and Klotzbach said.

Another weird thing is that Melissa sat offshore of mountainous Jamaica for awhile before coming inland.

Usually mountains, even on islands, tear up storms, but not Melissa.

“It was next to a big mountainous island and it doesn’t even notice it’s there,” McNoldy said in amazement.

Warm water is the fuel for hurricanes.

The hotter and deeper the water, the more a storm can power up.

But when storms sit over one area for awhile — which Melissa did for days on end — it usually brings cold water up from the depths, choking off the fuel a bit.

But that didn’t happen to Melissa, said Bernadette Woods Placky, chief meteorologist for Climate Central, a combination of scientists and journalists who study climate change.

“It’s wild how almost easily this was allowed to just keep venting,” Woods Placky said.

“This had enough warm water at such high levels and it just kept going.”

Warm water fuels growth

Melissa rapidly intensified during five six-hour periods as it hit the extreme rapid intensification level, McNoldy said.

And then it jumped another 35 mph and “that’s extraordinary,” he said.

For meteorologists following it “just your stomach would sink as you’d see these updates coming in,” Woods Placky said.

“We were sitting at work on Monday morning with our team and you just saw the numbers just start jumping again, 175.

And then again this morning (Tuesday), 185,” Woods Placky said.

“It’s an explosion,” she said.

One key factor is warm water.

McNoldy said some parts of the ocean under Melissa were 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the long-term average for this time of year.

Climate Central, using scientifically accepted techniques of comparing what’s happening now to a fictional world with no human-caused climate change, estimated the role of global warming in Melissa.

It said the water was 500 to 700 times more likely to be warmer than normal because of climate change.

A rapid Associated Press analysis of Category 5 hurricanes that brewed, not just hit, in the Atlantic over the past 125 years showed a large recent increase in those top-of-the-scale storms.

There have been 13 Category 5 storms from 2016 to 2025, including three this year.

Until last year, no other 10-year period even reached double digits.

About 29% of the Category 5 hurricanes in the past 125 years have happened since 2016.

McNoldy, Klotzbach and Woods Placky said hurricane records before the modern satellite era are not as reliable because some storms out at sea could have been missed.

Measuring systems for strength have also improved and changed, which could be a factor.

And there was a period between 2008 and 2015 with no Atlantic Category 5 storms, Klotzbach said.

Still, climate science generally predicts that a warmer world will have more strong storms, even if there aren’t necessarily more storms overall, the scientists said.

“We’re seeing a direct connection in attribution science with the temperature in the water and a climate change connection, Woods Placky said.

”And when we see these storms go over this extremely warm water, it is more fuel for these storms to intensify rapidly and push to new levels.”

“This had enough warm water at such high levels and it just kept going.”

Warm water fuels growth

Melissa rapidly intensified during five six-hour periods as it hit the extreme rapid intensification level, McNoldy said.

And then it jumped another 35 mph and “that’s extraordinary,” he said.

For meteorologists following it “just your stomach would sink as you’d see these updates coming in,” Woods Placky said.

“We were sitting at work on Monday morning with our team and you just saw the numbers just start jumping again, 175.

And then again this morning (Tuesday), 185,” Woods Placky said.

“It’s an explosion,” she said.

One key factor is warm water.

McNoldy said some parts of the ocean under Melissa were 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the long-term average for this time of year.

Climate Central, using scientifically accepted techniques of comparing what’s happening now to a fictional world with no human-caused climate change, estimated the role of global warming in Melissa.

It said the water was 500 to 700 times more likely to be warmer than normal because of climate change.

A rapid Associated Press analysis of Category 5 hurricanes that brewed, not just hit, in the Atlantic over the past 125 years showed a large recent increase in those top-of-the-scale storms.

There have been 13 Category 5 storms from 2016 to 2025, including three this year.

Until last year, no other 10-year period even reached double digits.

About 29% of the Category 5 hurricanes in the past 125 years have happened since 2016.

McNoldy, Klotzbach and Woods Placky said hurricane records before the modern satellite era are not as reliable because some storms out at sea could have been missed.

Measuring systems for strength have also improved and changed, which could be a factor.

And there was a period between 2008 and 2015 with no Atlantic Category 5 storms, Klotzbach said.

Still, climate science generally predicts that a warmer world will have more strong storms, even if there aren’t necessarily more storms overall, the scientists said.

“We’re seeing a direct connection in attribution science with the temperature in the water and a climate change connection, Woods Placky said.

”And when we see these storms go over this extremely warm water, it is more fuel for these storms to intensify rapidly and push to new levels.”

Links :

Wednesday, October 29, 2025

Russia’s strategy to control Arctic resources

Researcher at the Arctic University of Norway and associate researcher at the Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Future Energy at Paris Cité University

- The Arctic has significant strategic potential for Russia, particularly in terms of hydrocarbons, with 80% of the gas produced on Russian territory coming from this region.

- However, given the current geopolitical conditions, Russian companies are finding it difficult to export and access Western technologies.

- While the militarisation of the Arctic is nothing new, since 2005 there has been an undeniable strengthening of Russia’s military presence in the region.

- A significant portion of the Russian army contingents present in the Arctic have been mobilised for the war effort in Ukraine.

- There are arguments for and against the idea that the Arctic could be the next front between Russia and the United States.

Left behind after the fall of the USSR, the Arctic has once again become a strategic priority for Moscow since Vladimir Putin came to power.

Rich in hydrocarbons and crossed by crucial maritime routes, the Far North now crystallises tensions between major powers.

But the invasion of Ukraine and Western sanctions have upended Russian ambitions in the region.

Florian Vidal, a researcher at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, analyses the economic and military stakes of this strategic space that could become a new front between Russia and the United States.

Fishermen fish on the ice of the Gulf of Finland against the backdrop of the nuclear icebreaker Yakutia, which has entered the Gulf of Finland for sea trials in St. Petersburg

Image by picture alliance / ZUMAPRESS.com | Artem Priakhin

Image by picture alliance / ZUMAPRESS.com | Artem Priakhin

#1 The Far North is a strategic economic zone from the Kremlin’s point of view

TRUE

Since Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000, the Kremlin’s interest in the Arctic has only grown.

After having been largely abandoned following the fall of the Soviet Union, Moscow has regained control of this area, as its great strategic potential, particularly in terms of hydrocarbons, has revived its polar ambitions.

Indeed, 80% of the gas and 60% of the oil produced on Russian territory comes from the Arctic region.

The exploitation of liquefied natural gas (LNG) on the Yamal Peninsula in the Kara Sea is undoubtedly symbolic of the success of the programme to reinvest in the region.

However, this flagship project remains dependent on the development of communication infrastructure dedicated to the transport and export of resources.

The development of the Northern Sea Route and its ports have been envisaged in tandem with the exploitation of the Arctic subsoil.

Until the invasion of Ukraine, the strategy had been successful: hydrocarbons generated 50% of federal budget revenues, while the Arctic contributed 17% to national GDP.

UNCERTAIN

There are two major caveats to the Kremlin’s geo-economic projections.

Firstly, there is no denying the structural trends in society, which are particularly evident in the northernmost parts of the country.

The demographic decline is a striking example of this, affecting even urban centres such as Murmansk, whose population has been steadily declining since the late 1980s.

Secondly, the large-scale invasion of Ukraine and the barrage of sanctions against Russia are, unsurprisingly, hampering investment and the progress of ongoing projects.

Russian companies are finding it difficult not only to export, but also to access the Western technologies they need for production.

For example, Novatek, which operates the Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG 2 projects, depended on the German group Siemens for the supply of gas turbine generators and vapour gas compressors.

With the implementation of sanctions in the banking sector, which targeted investment projects in the energy sector in the region since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Western countries have slowed down Russia’s financial capabilities, which has attracted only limited investment despite a shift towards BRICS+.

#2 Vladimir Putin has turned it into a militarised region

FALSE

This statement is partially inaccurate: the militarisation of the Arctic is not a new phenomenon.

Its origins date back nearly a century, with the early establishment of a military presence in the region.

The Northern Fleet was officially established under Stalin before the Second World War.

It should be noted that regional tensions were, in many respects, more intense during the Cold War than they are today.

TRUE

Since 2005, the Russian authorities have undeniably stepped up their military presence in the Arctic by reopening former naval and air bases dating back to the Soviet era.

In addition to modernising existing bases, new infrastructure has been created.

Led by the Ministry of Defence, this dynamic has transformed the region into a veritable technological showcase, displaying cutting-edge military equipment (hypersonic missiles, latest-generation combat aircraft, etc.).

Furthermore, on the Kola Peninsula, the Northern Fleet has also been modernised.

Its nuclear capabilities have been strengthened by the construction of new submarines.

All these developments serve a clear objective: to assert military superiority and strategic dominance in the area.

Today, the Nordic countries recognise this established state of affairs.

UNCERTAIN

A significant portion of the Russian army’s contingents in the Arctic have been mobilised for the war effort in Ukraine.

The capacity of conventional forces in the region has been considerably weakened by the destruction of military equipment and significant losses among combat units.

The coastline, which stretches for more than 24,000 kilometres and is dotted with islands and archipelagos, makes it a difficult area to cover.

To address these difficulties, one of the options being considered is the deployment of an armada of drones along the coast.

At the same time, a massive recruitment drive for 50,000 soldiers has also been announced to achieve a force of 80,000 soldiers in the Leningrad Military District, the region between Saint Petersburg and Murmansk.

#3 The Arctic could be the next battleground between Russia and the United States

TRUE

Awareness of this new military reality emerged during Donald Trump’s first term in office.

Mike Pompeo, then Secretary of State, did not hesitate to describe the increased Russian and Chinese presence in the area as a joint threat to the United States.

With the need to rebuild capacity, the Biden administration has pursued a policy of re-engagement in the region, championing freedom of navigation and committing to the development of a new fleet of polar icebreakers – the United States currently has only two.

President Trump’s volatility and controversial announcements, particularly his aggressive approach towards Greenland, could contribute to creating a climate of insecurity in the region.

One imperialist impulse could trigger another.

Russia, for its part, has its eye on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago.

The risk now is that the region will enter into a transactional, bilateral approach based on power relations, whereas since the end of the Cold War it has been distinguished by its institutional framework based on multilateralism.

FALSE

In this region, which is less prone to conflict, cooperation remains the preferred approach.

In fact, the Arctic states may be tempted to preserve the achievements of the post-Cold War era, in particular the Arctic Council, which could serve as an interface for resuming dialogue in the future.

Economic development, particularly in the joint exploitation of Arctic resources, could provide a basis for understanding between Washington and Moscow, thus offering leverage to prevent any military escalation.

Links :

- European Council on Foreign Relations : The bear beneath the ice: Russia’s ambitions in the Arctic

- Atlantic Council : Putin’s Arctic ambitions: Russia eyes natural resources and shipping routes

- ArticToday : Russia’s Arctic route sells speed, at the planet’s expense

- TheParlamientMag : Russia spies opportunity in warming Arctic

- BBC : The struggle for control of the Arctic is accelerating - and riskier than ever

- GeoGarage blog : Polar powers: Russia's bid for supremacy in the Arctic Ocean / U.S. is playing catch-up with Russia in scramble for the Arctic / Putin makes his first move in race to control the Arctic / Russia submits revised claims for extending Arctic shelf to UN

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

Seabed mining: a new geopolitical divide?

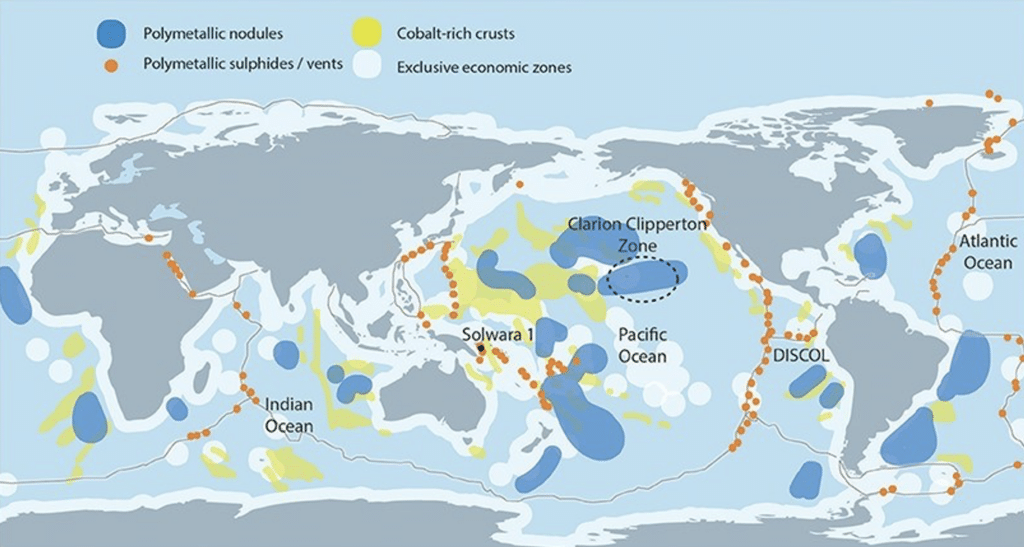

Figure 1: Map of the three main types of deep-sea minerals deposits4

Figure 1: Map of the three main types of deep-sea minerals deposits4From Polytechnique Insights by Emmanuel Hache, Emilie Normand & Candice Roche

Key takeaways

- As metals are at the core of national concerns, new mineral deposits in the deep sea tend to catch the attention of a growing number of actors.

- Coastal states have rights over resources located in their exclusive economic zones; beyond that, the sea is a common zone where the status of mining remains to be defined.

- Yet it is a zone rich in resources, particularly sulphide clusters, cobalt-rich crusts and polymetallic nodules.

- The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is negotiating a regulatory framework for the exploitation of deep-sea resources.

- These negotiations are giving rise to a new geopolitical sphere where traditional states alliances are questioned, and companies play an increasingly influential role.

In addition to the environmental insecurity caused by the climate crisis and the energy insecurity caused by the war in Ukraine, there is a looming mineral insecurity that could impede Europe’s energy and digital transitions.

Cobalt, copper, lithium, nickel, rare earths, and other critical minerals are essential for all low-carbon technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, batteries for electric vehicles or hydrogen fuel cells.

Hence, according to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA)1, consumption of these metals is expected to rise sharply by 2040.

The metals are now vital to all economic sectors, and are central to government concerns, driven by the global push to decarbonize, systemic rivalries between powers and a growing awareness of the planet’s limits2.

In this context, marine mineral deposits are drawing the attention of various states and companies.

According to Article 76 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, coastal states have sovereign rights over resources within 200 miles of their shores.

Beyond this limit, this is “the Area” where the sea and seabed belong to no-one despite the abundance of resources.

These deposits come in three forms: sulphide clusters, cobalt crusts and polymetallic nodules.

Polymetallic nodules are small pebbles lying on the seabed which are particularly sought after for their high nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese content.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is an area of particular interest due to its high concentration of nodules; the zone is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and covers approximately 4.5 million km² (the size of the European Union (EU)) (Figure 1).

With the International Seabed Authority (ISA) due to meet on 15 July3, it is timely to examine the issue of seabed mining.

Underwater exploration campaigns are currently underway, but no commercial extraction is on the agenda.

Deep-sea mining faces a several major obstacles:It is technically difficult and costly (1 to 5 million dollars for the extraction vehicles alone), not to mention the high and uncertain costs of operating and restoring the abyss;

It could have significant ecological impacts, including loss of biodiversity, major disruption of ecosystems and pollution, which are difficult to measure at present;

Most of the mining potential lies beyond the limits of national jurisdictions, in what the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea5 (UNCLOS) calls “the Area”, and states are struggling to agree on a unified regulatory framework.

The Area is administered by the International Seabed Authority (ISA)6, a UN entity defined by UNCLOS and created by the 1994 Agreement.

ISA has the exclusive mandate to organize and control activities in the Area for the benefit of mankind.

It is therefore up to ISA to set a framework for the exploration and exploitation of deep-sea mineral resources.

Since 2014, the organisation has been leading negotiations to develop an international mining code.

However, the task has proven difficult: while the Republic of Nauru has been pushing the UN body since 2021, and ISA Council and General Assembly are scheduled to meet this summer, they have already announced that finalising such a regulation would not be possible before 20257.

The drafting of this mining code thus marks a renewal of inter-state relations and brings forth a new geopolitical field, with its own issues, institutions and fault lines.

The seabed at the crossroads of traditional geopolitics

The issues surrounding the exploitation of deep-sea mining resources are at the crossroads of several traditional geopolitical fields:High Seas Geopolitics: The area is the focus of discussions about freedom of navigation, definition of exclusive economic zones, the sharing of fishery resources, and strategic defence, surveillance and intervention positions.

The high seas are a battleground for the strategic interests8 of states, particularly coastal ones, as they try to delineate the perimeter of this “Area” of uncertainty.

Underwater resources are seen as a new front for asserting sovereignty.Mining Geopolitics: Most major mining countries have a clear-cut opinion on deep-sea mining.

Proponents argue that it reduces the environmental impact of land-based extraction and prevents future supply disruptions.

Competition from these mineral resources is taken seriously by the traditional mining countries.

Some try to limit the scope by advocating a moratorium, as Chile does, or attempt to become mining superpowers, like China.

Similarly, potential deposits are already included in the supply security policies of countries, as Japan.Climate Geopolitics: Ocean has recently gained prominence as a distinct subject, dealt with in dedicated arenas9 and at the core of ambitious texts such as the recently adopted High Seas Treaty10.

Through this lens, underwater resources face the same tension as climate negotiations in general: preserving a key ecosystem while enabling all countries to develop.Commons Geopolitics: Designated as a “common heritage of mankind”, the deep seabed faces the same issues of equitable sharing as other res nullius.

A parallel can be drawn with Antarctica, which was protected from exploitation by the Antarctic Treaty System in 1959.

Supporters of a deep-sea mining ban advocate for a similar position, while other states assert their right to appropriation.

Negotiations on a possible deep-sea mining code thus involve these various analytical perspectives and give rise to a new geopolitical sphere with its own players, negotiating dynamics and timetable.

ISA11 is the central player in this sphere, responsible for both regulating the mining industry and protecting the seabed.

Strategies for influencing deep-sea mining are developed within its orbit.

ISA comprises 167 Member States – and the European Union (EU) – each with varying degrees of influence within the organisation.

Not all contribute to the organisation’s budget, 34 States have a permanent mission to ISA, 21 hold exploration contracts in the Area, 36 serve on the ISA Council and 41 have an expert on the Legal and Technical Commission.

Actors in tension between exploitation and protection of deep-sea resources

ISA is established as an omnipotent entity, tasked both with missions to protect marine environments, and to regulate activities within the Area and ensure equitable sharing of financial and economic benefits among states12.

These conflicting missions make the ISA’s position delicate and sometimes at odds with other UN structures.

For instance, UNEP13 warns about the uncertainties and potential environmental, social and economic risks of deep-sea mining14 when ISA is tasked with drafting a mining code to regulate its practice.

ISA is criticised for its lack of impartiality between its missions.

For example, its funding model means that the organisation can’t stop granting licences without threatening its own continuation.

Receiving $500,000 for each exploration licence issued, as well as an annual fee of $47,000 per contractor, ISA relies heavily on income from the licences it grants15 for its own funding.

Its functioning makes it more likely to act as a regulator rather than a protector.

Its operational mode also favours its regulatory mission over its protective one.

The organisation is criticised for its lack of transparency and its insufficient consideration of scientific advice.

Particularly concerning are the “two-year rule”16 activated by Nauru in 2021 and China’s veto17 on placing a discussion on the agenda for banning the granting of exploitation licences until regulations are adopted, raising fears of potentially silencing opposition to deep-sea mining within the ISA.

In ten years of negotiations on the mining code, the dividing line has shifted.

Originally centre around methods of regulating deep-water mining, the debate now questions the very desirability of mining these resources.

There are two distinct sides: on the one hand, countries such as China and Nauru which are in favour of speeding up the approval process (fast track), and on the other, countries such as Canada and Peru that are in favour of a 10 to 15-year moratorium, Brazil and Ireland which support a “precautionary pause”, and France which asks for a ban.

The movement advocating a moratorium on deep-sea mining is relatively recent and growing rapidly.

It began with the creation of the Alliance of Countries Calling for a Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium on the initiative of Fiji, Palau and Samoa in 2022.

It now includes 27 countries and continuous to gain momentum.

Several countries are actively engaged on this issue and want to position themselves as spearheads in the preservation of the deep seabed.

For instance, France recently signed an agreement with Greece18 joining it to the movement.

France aims to use its role as co-organiser (with Costa Rica) of the United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice in June 2025 as the culmination of the “Year of the Sea”.

However, the media coverage of the moratorium support movement should not overshadow the fact that most countries have not defined a clear position on the issue and that discussions on the subject are evolving rapidly.

Drilling in the Area: a new geopolitical fault line

Deepwater mining represents a new divide within traditional alliances, whether economic (G7, BRICS+, EU), geographical (CELAC, African Union, AOSIS) or strategic (OPEC, MSP etc.).

This makes international relations more complex, forcing states to form new and more ad hoc coalitions to defend their positions.

States mobilise four types of narratives, which clash in the media sphere to justify or reject seabed mining19.

The first two emphasize the potential benefits of mining: a) access to metals needed for the ecological transition by reducing environmental pressures on land, and b) profits created in the Zone that would be distributed among developing countries, becoming a tool for redistributive justice.

On the other hand, the next two narratives emphasize c) our lack of understanding of the seabed and the ecosystem services it provides to the planet, and d) the need for a strict protection policy, favouring metal recycling over a new extractive front.

As these arguments clash, three divide lines can be observed within allied blocs that illustrate these new tensions: among small island states, among Western countries and within what is considered the Global South.

The first group, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), made up of 44 states threatened by climate change, succeeded in having 1.5°C adopted as a warming target under the slogan “1.5 to survive”, thanks to their coalition at international negotiations.

However, they are now divided on the issue of deep-sea mining, between the economic potential of the resources and the risks to marine biodiversity.

Some, like Nauru and Tonga, want to exploit marine resources to finance their development.

By threatening to trigger the two-year rule, Nauru is even seeking to press for the adoption of a marine mining code by ISA.

Others, such as Vanuatu, Palau and Fiji, support a moratorium or even a total ban on mining.

Vanuatu and other islands in the “Melanesian Spearhead” group20 adopted a memorandum21 in August 2023 rejecting mining activities in their waters and calling for protection of the seabed, signalling the gap with their former partners.

In the West, there is a sharp division between those in favour of exploiting the seabed (United States, Norway, Japan, South Korea, etc.) and those advocating a pause or even a total ban (Germany, Canada, Finland, France, etc.).

The former stress the strategic importance of access to metals for the energy transition and national security, while the latter point to scientific uncertainty about the environmental impact.

The United States, which is neither a signatory to the UNCLOS nor a member of ISA, can hardly influence the development of marine mining rules, which is why a bipartisan resolution in November 2023 supports ratification of the treaty22 in the name of securing supplies of critical metals, particularly from China.

On the other hand, Canada and France are defending a moratorium and a total ban on seabed mining respectively.

This situation illustrates the division of the Western allies: despite shared concerns about access to metals, they are having strong disagreements over the development of undersea resources.

Finally, the “Global South”, a heterogeneous group not aligned with Western countries, is deeply divided over the exploitation of the seabed.

China and Russia are fervent supporters of exploitation: having already signed exploration contracts for all types of deposits, they would enjoy a technological lead if approved by ISA.

On the other hand, Brazil opposed mining projects in 202323, citing a lack of sufficient knowledge and calling for a 10-year pause in exploration.

Chile, a supporter of the moratorium along with Costa Rica, fears competition for its copper reserves, which currently account for 20% of the world’s land-based reserves.

The African countries, for their part, have no clear position: despite criticism, they have jointly called for a system of financial compensation24 in the event of exploitation to offset losses in their own mining sectors.

No formal opposition, then, but a demand for compensation for their own mining industries.

So the motivations on both sides of the divide are diverse: access to new resources, technological superiority, a source of intelligence for supporters versus a risk to marine biodiversity, priority to protection and fear of economic competition for detractors.

The challenge of opening a new extractive frontier is creating major rifts within traditional alliances and upsetting the old coalitions.

In conclusion, the seabed is emerging as a new geopolitical arena, with its own rationales and fault lines.

As is typical of modern geopolitics, the role of states is being scrutinized.

Businesses have a key role to play in such a sphere.

Indeed, they can push for the exploitation of the seabed which will benefit them directly, as The Metals Company25 has done.

But they can also restrict the economic interest of these new resources by opposing their use, as demonstrated by 49 international companies that have signed a declaration in favour of a moratorium.

Additionally, the proactive role of NGOs under the umbrella of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition and the mobilization of the scientific community and civil society influence certain states, starting with France, to reverse their stance in favour of a moratorium on seabed mining.

It remains to be seen whether the forthcoming ISA negotiations this summer will reflect this range of positions.

Links :

1https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024/outlook-for-key-minerals↑

2https://www.nature.com/articles/461472a↑

3https://www.isa.org.jm/sessions/29th-session-2024/↑

4Kathryn Miller et al., ‘An Overview of Seabed Mining Including the Current State of Development, Environmental Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps’, Frontiers in Marine Science, 4 (2018), p.

418, doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00418.↑

5https://www.itlos.org/fr/main/le-tribunal/translate-to-french-the-tribunal/cnudm/↑

6https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/AIFM_rapport_annuel_du_SG_2023_Chapter1.pdf↑

7https://www.isa.org.jm/news/isa-council-closes-part-ii-of-its-28th-session/↑

8https://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/glossaire/montego-bay↑

9Conférences des Nations Unies sur l’Océan depuis 2017, les « Our Ocean Conference » (OOC) depuis 2014, One Ocean Summit en 2022.↑

10Conférence intergouvernementale sur la biodiversité marine des zones situées au-delà de la juridiction nationale (Biodiversity Beyond National Juridiction, BBNJ).↑

11https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/AIFM_rapport_annuel_du_SG_2023_Chapter1.pdf↑

12Missions définies par les neuf “directions stratégiques” du Plan Stratégique 2019–2023 de l’AIFM.

Le Plan Stratégique 2024–2028, en cours de négociation, garde ces mêmes neuf directions.↑

13Programme des Nations unies pour l’environnement, https://www.unep.org/who-we-are/about-us.↑

14“Deep-Sea Mining.

The environmental implications of deep-sea mining need to be comprehensively assessed”, UNEP, 2024.↑

15https://www.passblue.com/2021/11/08/the-obscure-organization-powering-a-race-to-mine-the-bottom-of-the-seas/↑

16La « règle des deux ans » activée par Nauru en 2021 faisant référence au paragraphe 15 de la section 1 de l’Annexe de l’Accord relatif à la partie XI de la CNUDM, stipule que si un pays notifie à l’AIFM qu’il souhaite commencer l’exploitation minière en eaux profondes, celle-ci dispose d’un délai de deux ans pour adopter une réglementation complète.

Or son activation par Nauru en 2021 et le dépassement du délai de deux ans font craindre une utilisation de cette faille juridique pour débuter des activités minières sans cadre réglementaire.↑

17https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023–07-31/in-the-race-to-mine-the-seabed-china-takes-a-hard-line?leadSource=uverify%20wall↑

18https://mer.gouv.fr/en↑

19Axel Hallgren, Anders Hansson, « Conflicting Narratives of Deep Sea Mining », Sustainability, 2021, 13(9).↑

20Alliance de cinq organisations et pays mélanésiens visant à promouvoir la liberté des territoires mélanésiens et à renforcer leur liens culturels, politiques, sociaux et économiques, https://msgsec.info/.↑

21https://msgsec.info/wp-content/uploads/documentsofcooperation/2023-Aug-24-UDAUNE-DECLARATION-on-Climate-Change-by-Members-of-MSG.pdf↑

22https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/03/29/us-deep-sea-mining-critical-minerals-china-unclos/↑

23https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Brazil.pdf↑

24https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/african-nations-criticise-push-fast-track-deep-sea-mining-talks-2021–07-27/↑

25The Metals Company, ex DeepGreen Metals, est une entreprise canadienne d’exploration minière sous-marine cotée en bourse.

Elle détient actuellement une licence d’exploration pour les nodules polymétalliques et est sponsorisée par trois États insulaires : Nauru, les Îles Kiribati et les Tonga↑

Monday, October 27, 2025

From Sandy Island to Bermeja: our curious obsession with places that don’t exist

From FarOutMag by Sam Farley

Today, we know more about the world around us and our history than we ever have before.

Social media and the internet has shown us countries and communities from around the globe.

You no longer need an expensive plane ticket to go and explore distant cities; now you just need a YouTube or TikTok account.

That’s given us a wealth of information and increased understanding of other cultures.

However, despite us learning more about the world around us, there’s a growing obsession with places that don’t even fucking exist.

Over recent years, there’s been a growing interest in what we’ll politely call alternative history.

Self-proclaimed historians such as Graham Hancock have detailed their views on The Joe Rogan Experience and in Netflix documentaries, despite having no credible evidence.

More concerning has been Hancock’s claims that real archaeologists are trying to cover up the truth, echoing the language that we’ve heard in medical and vaccine scientism over recent years.

For hundreds of years, there’s been interest in Atlantis.

This powerful, island nation was described by Plato in Timaeus and Critias, before being sunk into the depths of the ocean following a natural disaster.

Historians are yet to find any evidence that Atlantis existed, and the likelihood is that it was a fictional device used as an allegory to warn against greed.

That hasn’t stopped people from looking for it ever since, and our obsession with places that don’t exist has only continued to grow.

There are recent examples too, with Sandy Island being one of the most fascinating.

This small island was situation in the Coral Sea, to the northeast of Australia.

The first recorded mention was from the famous explorer Captain James Cook, who charted a “Sandy I” in September 1774, which was included in a map called the Chart of Discoveries made in the South Pacific Ocean just two years later.

A full 100 years later, the island was reported against by the whaling ship Velocity, which led to it being included on a number of maps, both in Germany and the UK, as well as being listed in the Australian maritime directory in 1879.

Self-proclaimed historians such as Graham Hancock have detailed their views on The Joe Rogan Experience and in Netflix documentaries, despite having no credible evidence.

More concerning has been Hancock’s claims that real archaeologists are trying to cover up the truth, echoing the language that we’ve heard in medical and vaccine scientism over recent years.

For hundreds of years, there’s been interest in Atlantis.

This powerful, island nation was described by Plato in Timaeus and Critias, before being sunk into the depths of the ocean following a natural disaster.

Historians are yet to find any evidence that Atlantis existed, and the likelihood is that it was a fictional device used as an allegory to warn against greed.

That hasn’t stopped people from looking for it ever since, and our obsession with places that don’t exist has only continued to grow.

There are recent examples too, with Sandy Island being one of the most fascinating.

This small island was situation in the Coral Sea, to the northeast of Australia.

The first recorded mention was from the famous explorer Captain James Cook, who charted a “Sandy I” in September 1774, which was included in a map called the Chart of Discoveries made in the South Pacific Ocean just two years later.

A full 100 years later, the island was reported against by the whaling ship Velocity, which led to it being included on a number of maps, both in Germany and the UK, as well as being listed in the Australian maritime directory in 1879.

The island then appeared on maps until 1974, which saw its initial removal from the French Naval and Oceanographic Service on their nautical charts.

However, it wasn’t until as recently as 2012 that the island was truly undiscovered by Australian scientists studying plate tectonics in the area, aboard R/V Southern Surveyor.

They’d realised that the various maps they had had discrepancies around the island, so went to check it out for themselves, before discovering that the island didn’t exist and the depths in the area were never less than 1,300 metres.

At this point, Sandy Island was quickly removed from maps across the globe, including Google Maps, and now serves as a reminder that some errors charted early in world exploration have continued to be mapped wrong since.

It’s when phantom islands and conspiracy theories meet that the real fun begins, as is the case with Bermeja, which was said to lie off the Yucatan Peninsula’s north coast in the Gulf of Mexico.

Bermeja appeared on maps as early as the 16th century and has been an ever-present for around 500 years.

That was until the 1970s and 1980s, when all eyes turned to the island, with Bermeja’s location meaning that Mexico could extend their exclusive economic zone, which would give it precious oil rights.

The Mexican authorities, excited at the potential windfall, tried to locate the island but couldn’t, with aerial surveys and satellite imagery all drawing a blank.

The consensus view is that, much like Sandy Island, this was a cartographic error that had never been picked up.

The evidence shows that this was far more likely than alternative theories such as erosion, rising sea levels or a shift in the sea bed.

It also bore a fertile breeding ground for conspiracy theorists, with some speculation that the CIA had somehow destroyed the entire island in order to protect the United States’ exclusive economic zone.

There are plenty more examples in history, such as the Rochefort Islands, which were again reported by Captain Cook, Thule, which was described by Pytheas in the fourth century and the Isle of Demons, a monster-filled island that was believed to be near Newfoundland.

While we now know so much about the past and our history, there’s always fascination in finding out something new, something that’s been hidden from us.

The intrigue and mystery of a Sandy Island or a Bermeja and the CIA conspiracy are captivating and considerably more interesting than the reality that they are simply the result of hundreds of years-old human errors.

Or maybe that’s what the New World Order want us to think, I’ll see you in Atlantis.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : South Pacific Sandy Island 'proven not to exist' / How a fake island landed on Google Earth / These imaginary islands only existed on maps / Ancient maps show islands that don't really exist / Exploration mysteries: Phantom islands / 'The Phantom Atlas' book review: paps with gaps / Mystery of the phantom islands solved: Lands that ... / The mysterious disappearance of Jeannette Island ...

Sunday, October 26, 2025

Baluchon, Yann Quent's 4m sailing boat

Links :

- PBO : Yann Quenet from France to Canada in a 4m boat

- GeoGarage blog : Itinary of an unwise sailor

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)