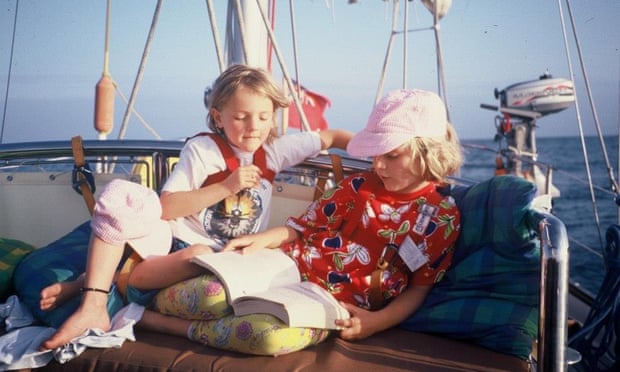

Elle Hunt with her sister on the family boat.

Photograph: Elle Hunt

From The Guardian by Elle Hunt

Oceans are central to the story of civilisation – so why do so many of us feel disconnected from them?

It was on day 11, I think, that I stopped getting out of bed at all.

I had already let my hygiene standards slip to the point that a large knot was starting to form in my hair.

Later my mother would have to cut it out with scissors.

She didn’t mind.

We were all in the same boat.

I was nine years old, and nearly two weeks into sailing across the Atlantic with my family.

My father had sailed all his life, and introduced my mother to it; and they spent years preparing to sail around the world.

Including my little sister, that made four of us aboard a 52ft yacht – our home for four years from 2000, in which time we got from Dorset to New Zealand.

The longest period we spent entirely at sea was 21 days, and we did so twice: from La Gomera in the Canary Islands to Barbados, and then from the Galápagos Islands to Nuku Hiva, in French Polynesia.

The first trip I remember spending mostly in bed, below deck in the dark, listening to Wings on cassette, forging a new relationship to time.

I grew used to observing the ebb and flow of my thoughts with a languor that today would probably be praised as meditative.

The days slid by, mostly unbroken except for meals – you came to really anticipate meals – and milestones: quarter-way, halfway, crossing the equator, which we marked with little parties.

Not long after the sun had gone down, you’d go to sleep – partly because artificial light drained the boat’s battery, and partly because the sooner you went to sleep, the sooner another day would pass, and the sooner you would arrive.

(I was lucky – being nine, I was spared night watch.

My parents slept in alternating shifts of two hours for the whole journey.)

‘Not long after the sun had gone down, you’d go to sleep’

Photograph: Drew Buckley/Alamy

When we finally reached Bridgetown in Barbados, and set foot on land for the first time in three weeks, my knees wobbled, bracing for the next wave that didn’t come.

That transatlantic crossing is a well-trodden path, from 15th-century navigators from Italy and Spain to Greta Thunberg’s

voyage to New York last year.

All of history, in fact, can be charted from the world’s oceans, as David Abulafia attempts in

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans, a 1,000-page doorstopper that he nonetheless makes no pretence is either “complete or comprehensive”.

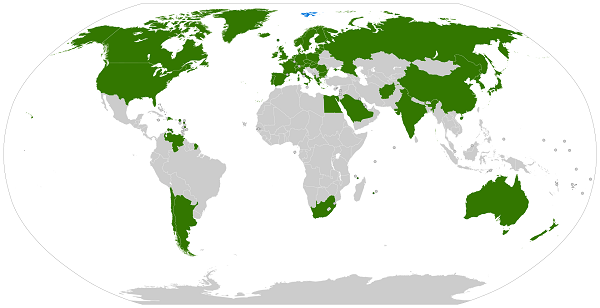

Connections made by sea “have brought together peoples, religions and civilisations” through conquest and colonisation, migration and trade, writes Abulafia, an emeritus professor of Mediterranean history at Cambridge – and in the process changed the world.

Much of it has been driven simply by curiosity, and the desire to accumulate knowledge, he says.

“Even if you go back to the time before Christopher Columbus, when the open Atlantic was very little known, the myths and assumptions that developed about it – the ‘sea of darkness’ and then, on the other hand, ‘the isles of the blessed’ – the fascination with what lies beyond the horizon was certainly an important part.”

I see elements of that in my father, whose 50-year passion for sailing goes well beyond what you might call a hobby.

“He’s only happy at sea,” says Mum, who is happy at sea, but also in her garden, or at a concert hall, or with her children.

My parents remain “liveaboards”, sailing international waters from New Zealand.

For them, it is a lifestyle that they have opted into, a way to see the world from a relatively unique vantage point.

Portuguese explorers arriving in Kolkata in 1498, painted by Alfredo Gameiro.

Shipping spices from India was a lucrative industry for Portugal.

Yet for most of history there has also been “a mercenary dimension” to ocean exploration, says Abulafia, “the wish to exploit”: “You know you’re taking risks, but these are risks that can bring you the most fantastic returns.”

Maritime trade has been more productive and enduring than the

Silk Road; in the 16th century, shipping spices from India proved so lucrative for Portugal that the Portuguese king made disclosing the route punishable by death.

The movement of not just goods, but people has been another constant – whether their migration was forced, such as by invasion or the slave trade; or voluntary, in search of a new life and opportunities.

Passages have been guided by the

trade winds and currents that drive

climate and weather all over the world.

More than 70% of the globe is covered by ocean; it produces around half the oxygen we breathe, and absorbs half of all man-made carbon dioxide.

At many levels, the story of civilisation is a story of the seas – but it is easy to overlook that from land.

Most people, even those who live by the coast, have no more personal connection to the sea than the limited or conditional view afforded by a passion for water sports, say, or the odd trip to the seaside.

A more intimate relationship can be incompatible with conventional ways of life and maybe – the knot in my hair might attest – its quality.

At the same time it changes you, in what can feel like a very profound way.

It was only relatively recently, I’m embarrassed to say, that I realised that my experience was not universally shared – that not everyone had known the open ocean, with no land in sight in any direction for many miles.

No other boats, either – just endless sea, sometimes even indistinguishable from sky; an expanse of grey or blue, entirely uninterrupted, except by you.

It is hard to convey what that feels like, the effect that it can have.

You feel dwarfed and insignificant, of course – but the mind cannot hold on to reverence for long.

I remember it more often playing tricks on me, registering patterns and shapes in the movements of the wave – my brain determinedly generating interest, overlaying meaning, as though it could not make sense of there being only water everywhere.

Elle Hunt aged about nine in the bosun’s chair, with her father Anthony.

Even as a child, though, there was something about being at sea that made me feel well: more vital, clear-headed.

In fact the benefits of “

blue space”, for body and mind, have been established by decades of research, from environmental factors such as more vitamin D and less polluted air and the increased activity that tends to go with being in nature.

More significant is the psychologically restorative effect, where the movement of water – its literal immersiveness – can force attention outwards, beyond the self.

But these effects on mood tend to be most acute at coastal margins, where the sea meets the land.

“The optimal environment has both,” says Dr Mathew White, an environmental psychologist with BlueHealth.

“If you’ve ever been on a cruise, or crossed to France, it’s pretty boring out there when you can’t see the coast.”

As a crew member on the

inaugural voyage from New York to Macau in 1784 grumbled of their smooth passage: “It has been one dreary waste of sky & water, without a pleasing sight to cheer us.” Abulafia paraphrased: “One went to sea for excitement, and all that happened was that the captain fell against a railing and bruised his head and arm.”

He suspects that some ships’ diarists exaggerated the risk of storms and shipwreck so as to enliven accounts “of a flat sea and neutral sky for days and days”.

Yet, in imagining a life at sea, most people seem less inclined to think of tedium than terror.

Many have told me that the thought of being stranded in the open ocean is one of their greatest fears; I’m not sure that they would single out being lost in a forest, for example, or on a snowy mountain in the same way, though all three landscapes are alien and potentially dangerous.

In fact the first question I am most often asked about my childhood is “Were there any storms?” or, more to the point: “Were you scared?”

The answers are yes, only one, a freak occurrence overnight; and no – I slept through it.

My parents were highly risk-averse, setting out for sea only when the weather forecast was favourable and they had supplies – food, medical, electrical – to account for every possible eventuality.

HMS Erebus in the Ice, 1846, by François Etienne Musin.

The vessel had to be abandoned in the Arctic ice on a later journey.

Photograph: National Maritime Museum

The exhaustive (and expensive) logistics tend to be glossed over in the other image people have of being at sea – the romantic one, of chucking it all in and sailing off into the sunset.

Whether or not this idea appeals to you

was found by data scientists at the dating app OkCupid to be one of the strongest predictors of romantic compatibility; I know enough to answer no.

Both scenarios, the worst-case and the rose-tinted, are telling of the disconnect most people feel from the ocean.

A sense of trepidation has figured in seafaring through history, except among those whose knowledge and mastery of the ocean was evolved over several millennia to seem almost innate – the early Polynesian navigators of the Pacific, the ancestors of the New Zealand Māori and Hawaiians.

There could be a genetic predisposition towards how we feel about travelling the seas: DRD 4-7R, the so-called “wanderlust” gene, is thought to be present in about 20% of the population.

In his book

On the Ocean, the archaeologist Sir Barry Cunliffe pointed to scientific findings that this impulse to travel, “to satisfy an innate curiosity”, could be one explanation for why “the unknown engages the human imagination, and draws the curious out of the familiar place they inhabit into the threatening, but ever exciting space beyond”.

Even if my parents have wanderlust in their DNA, I’m not sure it was handed down to me.

Though I spent the first half of my life sailing, I acquired none of the skills – I couldn’t even manage a bowline knot.

I have blamed it on my being a child, but the truth is I have never had any interest in boats beyond as a means of accessing the open ocean.

I still feel a strong connection to the sea – but it has been challenging to maintain in my adult life, from the tower block in south London where I now live.

When I am struggling to get to sleep I play ocean sounds through my phone, a crude attempt to simulate the limitlessness, even transcendence, I remember feeling out in open water.

The ocean presents a potential passage through history, like handling an ancient piece of pottery; only more so, because it “is alive, like a person”, to paraphrase an Indigenous Australian saying.

You can be claimed by the sea without drowning.

I feel its absence on a bodily level like a mineral deficiency, and make regular visits to the coast to “top up”, as the geographer Catherine Kelly evocatively

put it.

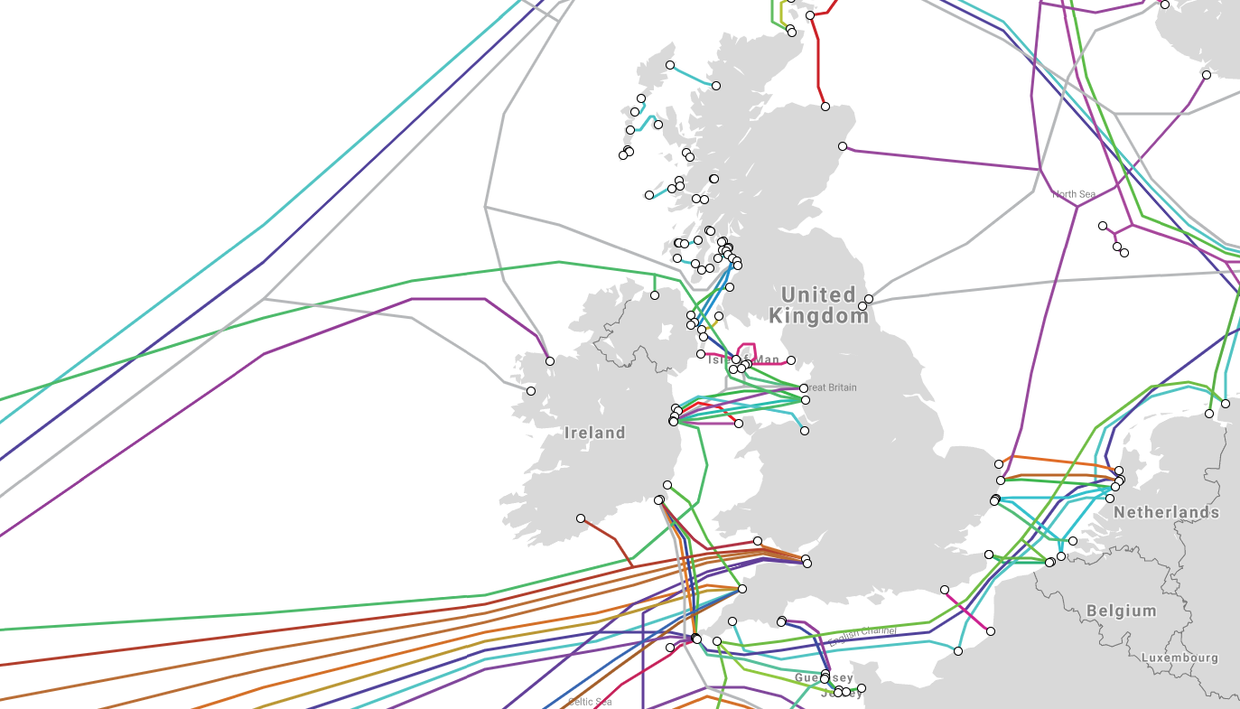

Now, although long-distance passenger travel by sea has become almost unheard of, Thunberg’s voyage across the Atlantic, and

the growing “no-fly” movement to cut down on carbon emissions, could suggest turning tides.

The oceans face considerable challenges themselves, from plastic pollution and deep-sea oil drilling, to unsustainable shipping and fishing.

The rising acidity of the Pacific Ocean is

causing crabs’ shells to dissolve.

Warming temperatures have already opened up

new trade routes over the top of Russia and Canada.

We face the beginning of a new chapter in the history of oceans – for us along with them.

Abulafia notes that rising sea levels have been suggested as a precipitating factor in past migration, forcing people to go in search of new land.

A

study last year predicted that warming temperatures will raise sea levels by 30cm by the end of the century, on top of the contribution from melting ice and glaciers.

These are uncharted waters that humanity is navigating – but not, there is some comfort in acknowledging, for the first time.

Links :