From Mongabay by Michelle Carrere- An investigative collaboration by Mongabay Latam, Ciper in Chile, Cuestión Pública in Colombia, and El Universo in Ecuador looked at illegal fishing and the threats it poses to Latin America’s marine sanctuaries.

- The investigation revealed suspected illegal fishing activities in marine protected areas in those three Latin American countries as well as Mexico.

- Many Latin American marine protected areas do not have enough surveillance or budget to prevent these crimes, and in some cases lack even a management plan defining a monitoring strategy.

- It is in this context that foreign fleets, particularly from China, including boats with a history of illegal fishing, also cross marine sanctuaries during their journeys.

After drugs and arms trafficking, illegal fishing is the third most lucrative illegal activity in the world. It is estimated that around 26 million tons of fish and other marine resources are caught illegally every year to supply a black market worth up to $23 billion.

Illegal fishing takes many forms, one of which involves fishing inside marine protected areas that have been created to safeguard the biodiversity within them.

A team of journalists from Mongabay Latam, Cuestión Pública in Colombia, El Universo in Ecuador, and Ciper in Chile, with the advice of satellite-monitoring experts and scientists, analyzed the movement of boats within marine protected areas over a five-year period between 2015 and 2020.

This research revealed illegal fishing in marine sanctuaries in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico. These four countries are among the top six in Latin America with the largest amount of protected marine territory, but the findings raise questions about whether they have the tools to control, monitor, and stop such illegal activities within their marine protected areas.

What the images reveal

The ability to track a boat’s movements in the ocean depends on whether it has a satellite device on board.

The device “is essentially a box that is in connection with satellites in orbit,” says scientist Fabio Favoretto, a member of DataMares, a civil society organization that analyzes data on fishing in Mexico and that collaborated with Mongabay Latam in analyzing the information for this research.

The device sends a signal every hour to a satellite indicating the boat’s position, speed, and course — information that allows researchers like Favoretto to later see, on a computer, the location of the boat, its trajectory, its speed, and how long it is taking.

When a boat is fishing, “many times, the first thing it does is slow down and then start to make turns or changes of direction,” said Favoretto, who is also a professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur.

He points out that boats can behave differently depending on the type of fishing gear they use. “Some use purse-seine nets and characteristically have circular movements.

Others, which are trawlers, simply slow down and then follow a straight line.

With experience and knowledge of these types of gear you can recognize these patterns,” he said.

This Global Fishing Watch map shows some of the fishing activity in the world.

Press play to start the video and use the + and – buttons to zoom in and out of the map.

There are different online platforms that show the position and route of boats at sea. One is Global Fishing Watch, whose algorithm combines numerous variables, including those Favoretto described, to identify when a boat might be fishing.

Although these tools have a high degree of certainty, to be able to assert that a boat has been out fishing requires in-person confirmation.

So countries use this technology to send their navies or fishing control authorities to certain locations to confirm fishing activity.

“We are never 100% sure. There is always a small percentage of error, but not because the model is wrong,” Favoretto said.

“This error could be because they [the boats] made the maneuver, but did not fish … the net came up empty. What I am 100% sure of is that they did something they normally do when they are fishing.”

The suspicious activities observed in this investigation through satellite monitoring have been cross-checked with other sources to determine which boats have a history of illegal fishing and which companies are behind such activity.

The findings

In Mexico, we observed 17 boats bearing a Mexican flag and 1 bearing a U.S. flag carrying out suspicious fishing activities within Revillagigedo National Park, which is home to endangered sharks and manta rays, and where fishing is prohibited.

Despite these findings, since December 2018, only three boats have been reported for alleged illegal fishing in this protected area.

In Colombia, we observed that boats bearing a Panamanian flag and a Colombian fleet from the Seatech company (from the well-known tuna brand Van Camp’s) operate in Yuruparí-Malpelo National Integrated Management District, adjacent to Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary, where industrial fishing is not permitted.

Some of the boats have a history of illegal fishing and even of shark finning — the practice of catching sharks and cutting off their fins before throwing the fish back into the sea.

Shark finning is illegal in Colombia.

Image by Juan Mayorga.

Image by Juan Mayorga.

Seatech benefited from tax reforms after the company and its managers donated 480 million pesos, roughly $155,000, in 2018 to the campaigns of candidates aligned with the uribista movement, a dominant strain in Colombian politics.

In all four marine protected areas we analyzed, the surveillance and budget allocated to control is insufficient.

In some cases, management plans and a monitoring strategy have not even been created. In other words, many marine protected areas are currently parks in name only, making them more vulnerable to illegal fishing.

It is in this context that

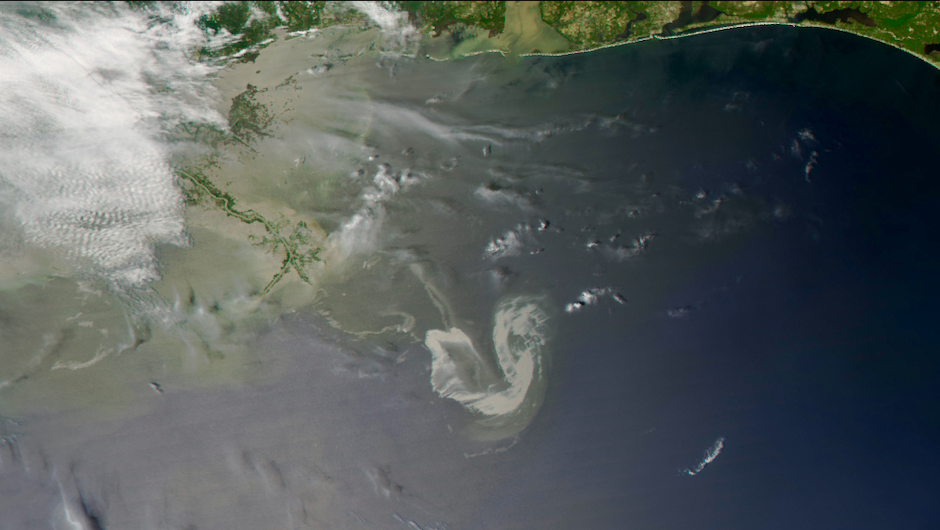

Chinese fleets move around the boundaries of the territorial waters of four South American countries to fish for giant squid (Dosidicus gigas), even passing through marine protected areas on some occasions as part of their journeys.

At the beginning of June last year, a Chinese fleet of around 260 boats reached the boundaries of the Galápagos exclusive economic zone to fish for squid.

For days, this group of boats, which artisanal fishermen described as “a giant city” in the middle of the sea, concerned scientists and government officials.

Although there were no reports of any of these boats entering Ecuadoran waters to fish illegally, their presence alarmed fishing authorities, the navy and even President Lenín Moreno, who ordered the creation of a committee to design a protection strategy for the Galápagos Islands.

The illegal fishing records of some of the Chinese boats were key to the Ecuadoran government’s decision.

Hammerhead sharks in the waters of Revillagigedo. Image courtesy of National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP)/Erick Higuera.

Hammerhead sharks in the waters of Revillagigedo. Image courtesy of National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP)/Erick Higuera.

During this same period, 149 of the boats shut down their satellite systems and “some boats even changed their identification,” said Darwin Jarrín, commander of Ecuador’s Navy at the time.

Turning off the satellite signal is often indicative, though not conclusive, of a boat engaging in criminal activity.

In the case of Chile, we found Chinese fleets crossing

Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park, the largest marine protected area in Latin America, during their long journeys across the region.

When this story was originally published in Spanish in October 2020, these boats were near Peruvian territorial waters and had begun to move south, putting Chilean authorities on alert.

This investigation identified the companies that own at least 140 of these boats; 95 of them are operated by just 10 companies.

Most of these companies are based in the city of Zhoushan, on the East China Sea.

Until a few years ago this was one of the focal points of the Chinese fishing industry, but its resources have now been depleted.

At least three boats with a history of illegal fishing have moved in or around the Galápagos and Nazca-Desventuradas marine parks in the last five years.

A difficult crime to trace

Illegal fishing not only has devastating consequences for ocean biodiversity, but also for the economies of coastal communities that make a living from fishing, and for global food security.

The biggest problem is that detecting illegal fishing is difficult, according to Juan Mayorga, a data scientist who heads an alliance of three institutions using technology to further marine science and conservation: the Sustainable Fisheries Group of the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the U.S.; National Geographic’s Pristine Seas marine conservation program; and Global Fishing Watch.

Unlike forests, where illegal logging is visible, fishing crimes at sea happen underwater; so after a crime has been committed, it is not possible to see that prohibited marine resources have been taken.

Moreover, “those carrying out the illegal activities do not want to be seen,” Mayorga said.

“So the vast majority of these boats are going to turn off their tracking devices if they have one” in order to avoid detection.

Even if the ships leave their tracking devices on, “in many countries, legislation and laws are a couple of steps behind the technology, with this kind of evidence still not accepted in legal cases.

This means that we have to intercept the boats, which is a much more expensive operation,” he said.

Destruction of the Fu Yuan Yu Leng’s illegal cargo in 2017. The vessel was caught with its freezers full of sharks near the Galápagos Islands. Image courtesy of Galápagos National Park.

Destruction of the Fu Yuan Yu Leng’s illegal cargo in 2017. The vessel was caught with its freezers full of sharks near the Galápagos Islands. Image courtesy of Galápagos National Park.

In this respect, Alex Muñoz, National Geographic’s Pristine Seas director for Latin America, noted that “in addition to the difficulty of detecting illegal activity there is the weakness of the legal and judicial systems in prosecuting crimes committed at sea in the courts.”

According to Muñoz, it is for this reason that “countries often simply choose to persuade ships to leave national waters rather than arresting them and initiating legal proceedings against them, as the evidential systems are very outdated.”

In other words, Muñoz said, “it is very difficult to prove the existence of a crime and the fines or other sanctions are very weak, meaning it is not worth the effort for sanctions that tend to be very minor.”

Although the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) placed the global total of fishing boats at 4.56 million in 2018, this figure is only an estimate as it is not possible to determine the number of boats at sea with certainty, according to Mayorga.

The Global Fishing Watch platform tracks approximately 80,000 vessels via their automatic identification system (AIS) and another 5,000 via their vessel monitoring system (VMS), another satellite system. “We are talking about 85,000 boats, but there is simply no other organization, no other group, that can give us more

That is what there is, that is what we have,” Mayorga said.

The importance of marine protected areas

Oceans generate most of the oxygen we breathe, absorb a large amount of our carbon dioxide emissions, regulate the climate, and feed the world’s people.

The value of oceans as an asset amounts to $24 trillion a year, according to a “conservative” calculation in a 2015 WWF

report.

Yet science has already shown that

66% of the marine environment has been significantly altered by human activity,

34% of fish stocks are overexploited, and populations of marine vertebrates declined by

49% over a recent 40-year period.

This degradation is increasing due to pollution, rising water temperatures caused by climate change, and ocean acidification as the ocean absorbs excess CO2 from the atmosphere.

To reverse these problems, marine protected areas are essential.

They have already been shown to benefit fisheries since they serve as nurseries for biodiversity.

This is why most countries committed to protecting at least 10% of their maritime territory by the end of 2020.

While many countries fell short of this target, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico are among those that met it.

In fact, Latin America as a whole has made significant progress in protecting the ocean: in 2000 it had protected only 1.43% of its sea area, a figure that has since increased to 23.6%, according to the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD).

How much marine territory is protected in Latin America?According to a United Nations Environment Programme

report, however, “the physical area covered is just one part of the commitment […]

For marine protected areas to be truly effective they need strong governance to influence human behaviour and reduce the impacts on the ecosystem.”

Part of that governance involves each protected area having a management plan that sets out how the area’s marine resources will be protected.

In Chile, five of the 28 marine areas with some level of protection have a management plan. In Colombia, 13 of 18 do; in Ecuador, it’s eight of 11; and in Mexico, 36 of 37.

Satellite systems show that when a marine protected area is created, fishing activity immediately changes: boats leave the area (especially from fully protected parks) to allow sea life to recover. However, as this investigation shows, there are exceptions.

Mayorga pointed out that the development of management plans requires the same kind of patience as the unfolding of the biological, social and economic benefits of marine protected areas.

However, he said, it is important to remember that “without management plans, marine protected areas will not be effective.”

Muñoz underscored the point: “A marine protected area must be well protected through mechanisms for monitoring fishing and through legal and judicial procedures that allow offenders to be sanctioned.”

This is a translation of the main story in a special series called “Illegal Fishing: The Great Threat to Latin American Marine Sanctuaries,” which was coordinated by Mongabay Latam and Ciper (Chile), Cuestión Pública (Colombia) and El Universo (Ecuador). It was originally published here on Oct. 6, 2020, on our Latam site, where you can find links to the other stories in the series.

Beam trawlers’ heavy chains are dragged along the seabed, releasing carbon into the seawater.

Beam trawlers’ heavy chains are dragged along the seabed, releasing carbon into the seawater.

Confined living conditions on cruise ships mean that disease outbreaks aren’t uncommon.

Confined living conditions on cruise ships mean that disease outbreaks aren’t uncommon. Brand new ships, such as P&O Cruises’ Iona, were built according to past demand and will enter service in a tough market.

Brand new ships, such as P&O Cruises’ Iona, were built according to past demand and will enter service in a tough market.

Image by Juan Mayorga.

Image by Juan Mayorga. Hammerhead sharks in the waters of Revillagigedo. Image courtesy of National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP)/Erick Higuera.

Hammerhead sharks in the waters of Revillagigedo. Image courtesy of National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP)/Erick Higuera. Destruction of the Fu Yuan Yu Leng’s illegal cargo in 2017. The vessel was caught with its freezers full of sharks near the Galápagos Islands. Image courtesy of Galápagos National Park.

Destruction of the Fu Yuan Yu Leng’s illegal cargo in 2017. The vessel was caught with its freezers full of sharks near the Galápagos Islands. Image courtesy of Galápagos National Park.