Saturday, January 21, 2023

The best islands in Europe for getting away from almost everyone

From legendary nightlife hotspots to volcanic outposts far off the continent's mainland, Europe has islands in spades.

But for every Mykonos, Ibiza or Santorini, there's someplace lesser known and equally lovely to escape to where you can ditch the crowds and get closer to nature.

Here are some of the best islands in Europe for getting away from almost everyone:

Schiermonnikoog, the Netherlands: Schiermonnikoog in the West Frisian Islands is home to about 950 people -- perfect for a peaceful getaway.

Sander van der Werf/Adobe Stock

Sander van der Werf/Adobe Stock

Schiermonnikoog, the Netherlands

The Netherlands is better known for canals, dikes and tropical Dutch Caribbean Islands like Bonaire and Curaçao than the sandspun isles along the country's North Sea coast.

But one of Europe's most peaceful island escapes awaits on Schiermonnikoog in the West Frisian Islands, located off the Netherlands' northern coast across a shallow inlet of the North Sea called the Wadden Sea.

Home to just 950 people and a lone town, Schier, as locals call their island, is primarily national parkland, covered in dunes and forests and with some of Europe's most pristine beaches.

"Besides the beautiful nature and the vastness of it, there is not much to do on the island.

And that is precisely the charm," says Annemarieke Romeijn, who has a holiday home on Schiermonnikoog and has been visiting all her life.

Only residents are allowed to drive cars on the island, which you can get to from the mainland Dutch village of Lauwersoog by hopping a 45-minute ferry.

Once there, visitors can spend their time hunting for pieces of amber washed ashore on the island's wide white sand beaches, take kitesurfing lessons along natural sandbanks and cycle and hike the island's miles of lonely trails.

Heimaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland

There are more puffins than people here, but human visitors are richly rewarded.

Thor/Adobe Stock

Thor/Adobe Stock

Home to more puffins than people, the island of Heimaey in the Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands) off Iceland's south coast looks straight from a story book, with emerald green cliffs dotted with sheep, a sweeping black sand beach and sea caves yawning from its rugged coastline.

"The view alone coming into Heimaey takes your breath away," says Eyrún Aníta Gylfadóttir of Hotel Ranga, a hotel on mainland Iceland that regularly sends guests on day trips by ferry to the Westman Islands, a 40-minute crossing.

"The harbor is surrounded by high cliffs and home to seabirds of many kinds such as puffins, northern gannet, northern fulmar and Manx shearwater," she says.

A cataclysmic volcanic eruption on Heimaey in 1973 covered the area in 200 millions tons of ash and lava but miraculously just one death was reported.

Today, utter peace reigns, with lonely hiking trails to explore and vast ocean views.

Only about 4,500 people share Vestmannaeyjar with nearly a million puffin pairs that make up the largest Atlantic puffin colony on the planet.

The breeding season, between April and late summer, sees birds careening from the cliffs and carrying fish to their young in cliffside burrows.

Flores Island, Azores, Portugal

Waterfalls trickle down an imposing rock face on the island Flores in the Azores.

aroxopt/Adobe Stock

aroxopt/Adobe Stock

One of the most remote islands in an already remote archipelago, Flores Island in the westernmost stretches of the Azores is a nature lover's dream.

Deep blue crater lakes, vivid green slopes, plunging valleys, waterfalls and boiling hot springs are among the otherworldly sights on the 55-square-mile volcanic island home to roughly 3,400 people, where you can arrive via flights from other Azorean islands

"On this island you have the sensation that you are in another world.

No pollution, no stress, no noise." says Gabriela Silva, 69, who was born on Flores and still lives on the island near an Airbnb she rents to guests.

"The sea all around is very clean, deep blue and you can dive in and feel the sensation of being in the house of gods."

Related contentAmericans are flocking to Europe's hot spots.

Here's where Europeans are going instead

One of the most magical sites on Flores is Rocha dos Bordões, a geological formation of basalt columns draped in vegetation that looks like the backdrop of a dinosaur film.

With just 26 rooms, Hotel das Flores is Flores' largest hotel, located in the island's main harbor town, Santa Cruz das Flores.

Vacation rentals are scattered throughout the island.

Naustholmen, Norway

Vacation rentals are scattered throughout the island.

Naustholmen, Norway

Naustholmen, Norway: This private island, owned by a Norwegian adventurer, hosts visitors for a range of outdoor experiences.

Alamy Stock Photo

Alamy Stock Photo

Visitors must fly into Bodø in Northern Norway then continue north by boat to reach this private island owned by Norwegian adventurer Randi Skaug, the first Norwegian woman to scale Mount Everest.

Naustholmen guests stay in rooms spread across three houses on the island and spend their days kayaking to white sandy beaches lapped by deep blue waters or hiking nearby peaks for views of the Lofoten Islands to the north.

They can also simply swing in a hammock (or even sleep overnight outside in one) and do nothing at all, surrounded by the silence and beauty of this remote place.

"Have lunch over the fire on a beach, go hiking across the spectacular Nordskot Traverse or hear a mini concert in a local cave," says Torunn Tronsvang, CEO of travel company Up Norway.

"This is a place which will give energy and inspiration."

Isle of Tiree, Scotland

"This is a place which will give energy and inspiration."

Isle of Tiree, Scotland

This turquoise paradise is off the western coast of Scotland.

Richard Kellett/Adobe Stock

Richard Kellett/Adobe Stock

One look at the turquoise and deep sapphire waters and perfect surf waves rolling onto its shores and it's clear why the Isle of Tiree is sometimes referred to as the Hawaii of the North.

The most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides archipelago, off mainland Scotland's west coast, 12-mile-long Tiree is known for its mild climate, clean air and beautiful white sand beaches that could easily be mistaken for the Caribbean in photos if not in person (August water temperatures are in the brisk upper 50s Fahrenheit, or about 14 Celsius).

Intrepid surfers know Tiree for its uncrowded beach breaks, and the eight-room Reef Inn caters to the board-riding crowd.

The annual Tiree Music Festival draws up to 2,000 attendees every July for a Scottish folk music extravaganza, but you'll most often have the island's mostly flat walking and cycling trails and 46 miles of gorgeous beaches to yourself.

Visitors arrive on Tiree via four-hour ferry rides from Oban or flights from Oban or Glasgow on Loganair.

Berlengas archipelago, Portugal

About six miles off the coast from Peniche, the Berlengas archipelago is an excellent scuba diving destination.

Luis Fonseca/iStockphoto/Getty Images

Luis Fonseca/iStockphoto/Getty Images

One of Portugal's most surprising island destinations awaits visitors arriving by boat for day trips or to camp overnight in the Berlengas archipelago, three groups of mostly uninhabited islands within the UNESCO-listed Berlengas Biosphere Reserve.

Roughly six miles offshore from the mainland Portugal town of Peniche, the archipelago is best known for the Fort of São João Baptista, a fortress dating back to the 1600s that commands an imposing presence atop a rocky outcropping on Berlengas Grande, the largest island in the chain.

Rooms can be booked at the fort's inn during the summer for overnight stays.

Berlengas Grande has campsites open during the summer where visitors can sleep overnight and feel all alone under the Milky Way.

"The landscape is arid but beautiful, and the sight of the Atlantic Ocean crashing around the islands is impressive," says Arlindo Serrao of Portugal Dive.

Serrao says the archipelago is one of the best places for scuba diving in Portugal, thanks to unique currents and a climate influenced by the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Mola mola (ocean sunfish) can sometimes be seen in the waters, and the islands are one of the most important places along mainland Portugal's coast for breeding seabirds.

Alicudi, Sicily, Italy

Alicudi, Sicily, Italy: Wild and rugged, Aliduci is the least inhabited of the seven islands in the Aeolian chain off Sicily's northern coast.

Dallas Stribley/The Image Bank Unreleased/Getty Images

Leave the "White Lotus"-inspired crowds to Taormina and make for the westernmost and most remote of Sicily's volcanic Aeolian Islands for an experience apart.

Wild and rugged, Aliduci is the least inhabited of the seven islands in the chain off Sicily's northern coast that include Stromboli and Lipari, among others.

Wild and rugged, Aliduci is the least inhabited of the seven islands in the chain off Sicily's northern coast that include Stromboli and Lipari, among others.

"It's the most wild island in Sicily.

They still use donkeys to transport goods around on Alicudi," says Sicilian Francesco Curione.

"If you're looking for quiet and a castaway feel, this is the place."

Alicudi's distinctive volcanic cone rises from the Tyrrhenian Sea to dramatic effect, with colorful fishing boats bobbing along the shoreline completing the postcard look.

Buying fish straight from the fishermen in Alicudi is not to be missed.

There are no cars here and only around 100 residents, so finding a quiet spot all to yourself is never an issue.

The higher you walk along lava stone steps leading up the volcanic slopes, the deeper the silence and escapism.

There are no hotels on Alicudi, but villa rentals and Airbnbs make it comfortable to settle in and stay awhile.

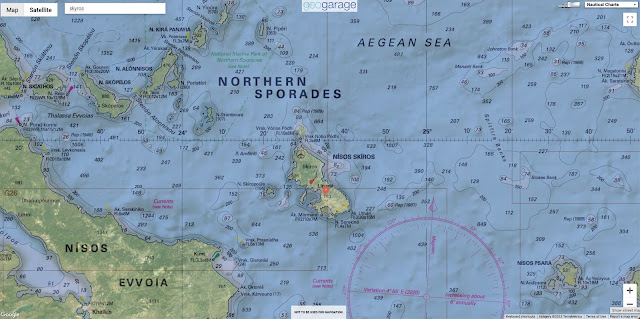

Skyros, Greece

Skyros is one of two dozen islands in Greece's Sporades chain.

dinosmichail/iStockphoto/Getty Images

dinosmichail/iStockphoto/Getty Images

Greek islands like Santorini and Mykonos in the Cyclades can get so sardined with tourists during the summer months that you might be left wondering what all the hype is about.

For a more isolated experience in the Greek islands, set your sights instead north in the Aegean Sea to the island of Skyros.

One of 24 islands in the largely uninhabited Sporades chain in the northwest Aegean Sea, Skyros is reached via flights from mainland Greece as well as by ferry from the mainland and other nearby Greek islands.

Once there, there are secluded beaches to explore, a Byzantine castle towering over the main town and sea and even an ancient breed of miniature horse, the Skyrian horse, that lives in the wild only on this island.

With the exception of the lead up to Lent -- when Skyros' famous carnival puts the island into nonstop party mode with parades and costumed revelry and an inundation of Athenians -- it's a supremely peaceful place.

Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland

Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland: Rathlin Island off the coast of Northern Ireland is home to only about 150 residents and thousands of nesting birds.

Andrea Ricordi/Moment Open/Getty Images

Andrea Ricordi/Moment Open/Getty Images

Stretching six emerald-hued miles long and just one mile wide, Rathlin Island off the coast of Northern Ireland is home to only about 150 permanent residents.

Visitors who arrive via a quick ferry crossing from Ballycastle on the mainland are transported to a wilderness of dramatic sea cliffs home to thousands of nesting birds that include puffins, guillemots, kittiwakes and razorbills.

Colonies of harbor seals and grey seals line Rathlin's remote inlets.

Hiking trails crisscross the ruggedly scenic island and experienced scuba divers are drawn underwater to explore the scores of shipwrecks just offshore that include the HMS Drake, torpedoed by a German U-boat during World War I.

Don't miss a visit to Rathlin West Light, a lighthouse built upside down on the rocks to better cut through the low, dense fog that often descends on the island.

Fasta Åland, Finland: Fasta Åland is the largest island in this archipelago and home to Mariehamn, the administrative capital of the Åland Islands.

Tuukka/Adobe Stock

Tuukka/Adobe Stock

Fasta Åland, Finland

In the Gulf of Bothnia between Sweden and Finland, the Åland archipelago has more than 6,500 islands, of which only about 60 are inhabited.

To say there's room to stretch out and breathe on these Baltic Sea islands is an understatement.

An autonomous region, the islands belong to Finland but are only 25 miles from Sweden, with Swedish as the official language.

Fasta Åland is the largest island in the archipelago and a good base for explorations.

Tour by bike to nearby islands linked by ferries and bridges or just settle into a vacation rental or hotel with a sauna and sea views for a relaxing reset.

HavsVidden offers a secluded escape on northern Fasta Åland with villas with their own saunas overlooking the rocky shoreline.

Links :

Friday, January 20, 2023

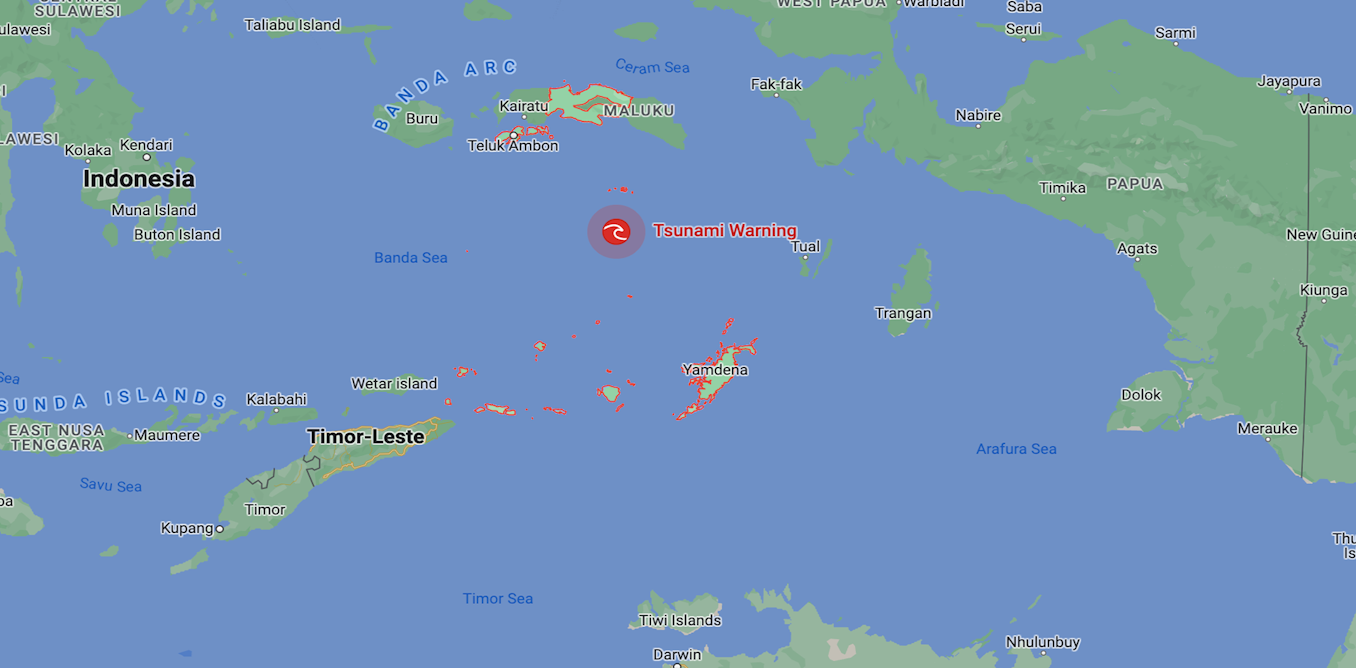

Maluku earthquake: why do some ocean earthquakes cause tsunamis while others don’t?

From The Conversation by Martin Van Kranendonk

We live on an active planet, one whose surface is constantly in motion, although imperceptibly to us most of the time.

Until an earthquake occurs.

This morning, just such an event happened in the seas north of the Indonesian Archipelago, where a strong (magnitude 7.6 on the Richter scale) earthquake shook the region and was felt as far afield as Darwin in Australia.

Impressive that over 2000 reports have been filed to @GeoscienceAus regarding this #earthquake in #darwin at 330am onwards!! Shows you the magnitude of this event. Also felt as far south as Tennant Creek and into the far Southern Kimberly. pic.twitter.com/2YpngjOkIb

— Karl Lijnders (@KLijnders) January 9, 2023

The Bureau of Meteorology advises there is no tsunami warning for Australia, while some parts of Indonesia are in watch and wait mode.

But what determines if a tsunami will occur?

But what determines if a tsunami will occur?

Grinding rocks

Only 70 years ago, it was considered our planet was rigid and affected only by slight sagging and raising of landscapes.

However, with the advance of technology in the 1950s we began to map the seafloor using sonar.

We could also measure the magnetic properties of the seafloor.

As a result, we’ve discovered the ocean floors are splitting apart at undersea mountain ranges known as mid-ocean ridges.

Additionally, oceanic crust (the part of Earth’s crust underlying the ocean basins) is being lost around the edges of most continents.

It is being returned deep into Earth’s mantle – the thick layer of semi-molten rock beneath Earth’s surface crust.

This happens at what are known as “subduction zones”.

Subduction zones are deep oceanic trenches where one tectonic plate dives down beneath another, generating earthquakes as the rocks slowly grind past one another.

The source of tsunamis

So why is it some earthquakes generate deadly tsunamis and others don’t?

Earth’s tectonic plates move across the planet’s surface at an average speed of around 10cm per year.

This speed was originally estimated based on changes in the magnetic seafloor properties, but has now been measured by satellites in space.

This movement is not a smooth process, since Earth’s crust is hard and experiences strong friction when the tectonic plates come into contact with one another.

As they move, this friction builds up stress in the rock, which is released every once in a while in the form of earthquakes.

In some places, earthquakes occur only occasionally but are very strong, while in others they happen more frequently and are weaker.

But earthquakes also vary greatly in terms of how deep they are generated below the surface.

This is because subduction zones continue for a long way down into the mantle.

The rocks remain cold and stiff for hundreds of kilometres down before they get hot enough from the internal heat of the planet to become soft.

And this is the main reason some earthquakes generate tsunamis and others do not.

Shallow subduction zone earthquakes actually displace the seafloor – either up or down – and also the ocean above it.

This happened with devastating effect in the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, located 24km deep and 9.1 magnitude on the Richter scale.

This single earthquake moved the crust 26 metres in seconds and lifted up the ocean, sending the crashing waves of a tsunami right across the Pacific Ocean.

Meanwhile last night’s 7.6 magnitude Maluku earthquake in Indonesian waters was not as strong and occurred at a depth of 105km.

At this depth, the energy and associated movement from the earthquake becomes dissipated into a million small fractures in the overlying rocks.

The energy also has to pass up through a wedge of the semi-molten mantle.

Thus, the surface expression of the earthquake is significantly weakened and we either get no ocean waves, or only small ones.

Because Earth’s plates move at a relatively constant rate and we have a record of earthquake activity for any particular part of Earth’s crust in the form of the geological record, we can predict roughly how often earthquakes should occur in any broad location.

Unfortunately, we do not yet have the technology to be able to predict exactly when or where an earthquake will occur.

But what we can do is identify areas at risk and build earthquake-resistant infrastructure in areas prone to earthquakes to prevent damage and loss of life.

Links :

Thursday, January 19, 2023

How did cartographers create world maps before airplanes and satellites? An introduction

From OpenCulture

Regular readers of Open Culture know a thing or two about maps if they’ve paid attention to our posts on the history of cartography, the evolution of world maps (and why they are all wrong), and the many digital collections of historical maps from all over the world.

What does the seven and a half-minute video above bring to this compendium of online cartographic knowledge? A very quick survey of world map history, for one thing, with stops at many of the major historical intersections from Greek antiquity to the creation of the Catalan Atlas, an astonishing mapmaking achievement from 1375.

What does the seven and a half-minute video above bring to this compendium of online cartographic knowledge? A very quick survey of world map history, for one thing, with stops at many of the major historical intersections from Greek antiquity to the creation of the Catalan Atlas, an astonishing mapmaking achievement from 1375.

The upshot is an answer to the very reasonable question, “how were (sometimes) accurate world maps created before air travel or satellites?”

The explanation?

A lot of history — meaning, a lot of time.

Unlike innovations today, which we expect to solve problems near-immediately, the innovations in mapping technology took many centuries and required the work of thousands of travelers, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, historians, and other scholars who built upon the work that came before.

It started with speculation, myth, and pure fantasy, which is what we find in most geographies of the ancient world.

Unlike innovations today, which we expect to solve problems near-immediately, the innovations in mapping technology took many centuries and required the work of thousands of travelers, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, historians, and other scholars who built upon the work that came before.

It started with speculation, myth, and pure fantasy, which is what we find in most geographies of the ancient world.

He knew of three continents, Europe, Asia, and Libya (or North Africa).

They fit together in a circular Earth, surrounded by a ring of ocean.

“Even this,” says Jeremy Shuback, “was an incredible accomplishment, roughed out by who knows how many explorers.”

They fit together in a circular Earth, surrounded by a ring of ocean.

“Even this,” says Jeremy Shuback, “was an incredible accomplishment, roughed out by who knows how many explorers.”

Sandwiched in-between the continents are some known large bodies of water: the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Phasis (modern-day Rioni) and Nile Rivers.

Eventually Eratosthenes discovered the Earth was spherical, but maps of a flat Earth persisted.

Greek and Roman geographers consistently improved their world maps over succeeding centuries as conquerers expanded the boundaries of their empires.

Eventually Eratosthenes discovered the Earth was spherical, but maps of a flat Earth persisted.

Greek and Roman geographers consistently improved their world maps over succeeding centuries as conquerers expanded the boundaries of their empires.

Some key moments in mapping history involve the 2nd century AD geographer and mathematician Marines of Tyre, who pioneered “equirectangular projection and invented latitude and longitude lines and mathematical geography.”

This paved the way for Claudius Ptolemy’s hugely influential Geographia and the Ptolemaic maps that would eventually follow.

Later Islamic cartographers “fact checked” Ptolemy, and reversed his preference for orienting North at the top in their own mappa mundi.

The video quotes historian of science Sonja Brenthes in noting how Muhammad al-Idrisi’s 1154 map “served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch, and French mapmakers from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century.”

Later Islamic cartographers “fact checked” Ptolemy, and reversed his preference for orienting North at the top in their own mappa mundi.

The video quotes historian of science Sonja Brenthes in noting how Muhammad al-Idrisi’s 1154 map “served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch, and French mapmakers from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century.”

The invention of the compass was another leap forward in mapping technology, and rendered previous maps obsolete for navigation.

Thus cartographers created the portolan, a nautical map mounted horizontally and meant to be viewed from any angle, with wind rose lines extending outward from a center hub.

These developments bring us back to the Catalan Atlas, its extraordinary accuracy, for its time, and its extraordinary level of geographical detail: an artifact that has been called “the most complete picture of geographical knowledge as it stood in the later Middle Ages.”

Thus cartographers created the portolan, a nautical map mounted horizontally and meant to be viewed from any angle, with wind rose lines extending outward from a center hub.

These developments bring us back to the Catalan Atlas, its extraordinary accuracy, for its time, and its extraordinary level of geographical detail: an artifact that has been called “the most complete picture of geographical knowledge as it stood in the later Middle Ages.”

Created for Charles V of France as both a portolan and mappa mundi, its contours and points of reference were not only compiled from centuries of geographic knowledge, but also from knowledge spread around the world from the diasporic Jewish community to which the creators of the Atlas belonged.

The map was most likely made by Abraham Cresques and his son Jahuda, members of the highly respected Majorcan Cartographic School, who worked under the patronage of the Portuguese.

During this period (before massacres and forced conversions devastated the Jewish community of Majorca in 1391), Jewish doctors, scholars, and scribes bridged the Christian and Islamic worlds and formed networks that disseminated information through both.

In its depiction of North Africa, for example, the Catalan Atlas shows images and descriptions of Malian ruler Mansa Musa, the Berber people, and specific cities and oases rather than the usual dragons and monsters found in other Medieval European maps — despite the cartographers’ use of the works like the Travels of John Mandeville, which contains no shortage of bizarre fiction about the region.

While it might seem miraculous that humans could create increasingly accurate views of the Earth from above without flight, they did so over centuries of trial and error (and thousands of lost ships), building on the work of countless others, correcting the mistakes of the past with superior measurements, and crowdsourcing as much knowledge as they could.

To learn more about the fascinating Catalan Atlas, see the Flash Point History video above and the scholarly description found here.

Find translations of the map’s legends here at The Cresque Project.

Links :

- Open Culture : The History of Cartography, the “Most Ambitious Overview of Map Making Ever,” Is Now Free Online / Download 91,000 Historic Maps from the Massive David Rumsey Map Collection / Why Every World Map Is Wrong / Animated Maps Reveal the True Size of Countries (and Show How Traditional Maps Distort Our World) / The Evolution of the World Map: An Inventive Infographic Shows How Our Picture of the World Changed Over 1,800 Years

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Oceans surged to another record-high temperature in 2022

The waters of the Gulf of Mexico

off Clearwater Beach, Fla., are tranquil on Sept.

26, two days before Hurricane Ian’s devastating landfall farther south on the Gulf Coast.

26, two days before Hurricane Ian’s devastating landfall farther south on the Gulf Coast.

(Octavio Jones/For The Washington Post)

From Washington Post by Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis

‘The fact that we’re seeing such clear increases in ocean heat content, extending over decades now, shows that there is a significant change underway,’ one long-time researcher says

The amount of excess heat buried in the planet’s oceans, a strong marker of climate change, reached a record high in 2022, reflecting more stored heat energy than in any year since reliable measurements were available in the late 1950s, a group of scientists reported Wednesday.

That eclipses the ocean heat record set in 2021 — which eclipsed the record set in 2020, which eclipsed the one set in 2019.

And it helps to explain a seemingly ever-escalating pattern of extreme weather events of late, many of which are drawing extra fuel from the energy they pull from the oceans.

“If we keep breaking records, it’s kind of like a broken record,” said John Abraham, a climate researcher at the University of St.

Thomas in Minnesota and one of the authors of the new research published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

The planet’s air temperature has been rising for decades, but it wobbles up and down and does not set records every single year.

Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service recently ranked 2022 as the fifth-hottest year on record for the atmosphere, with other expert rankings soon to follow.

The ocean doesn’t do the same dance.

It changes more slowly — and more deeply.

As climate change takes hold, natural ocean variations in temperature matter less and less, Abraham said, leading to a string of consecutive records in recent years, with 2018 being the last year that was not a record.

More than 90 percent of the excess warming that results from the planetary energy imbalance, in which more solar heating enters the Earth’s system than escapes again to space, winds up in the ocean, the researchers say.

Scientists began their record of ocean heat in 1958 because it is when measurements became dense enough, and accurate enough, to give a full global picture of the temperature trends down to considerable depths.

“Oceans contain an enormous amount of water, and compared to other substances, it takes a lot of heat to change the temperature of water,” Linda Rasmussen, a retired researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who was not involved in the work, said in an email.

“The fact that we’re seeing such clear increases in ocean heat content, extending over decades now, shows that there is a significant change underway.”

The new research suggests that the rise in heat contained within the upper roughly 1.25 miles of ocean water — an increase driven by a massive amount of absorbed energy measured in units known as zettajoules — represents the true pulse of climate change.

The amount of added heat in 2022 is around a hundred times larger than the total world electricity generation in 2021, the researchers said in a news release.

Why big fish sightings are on the rise

Climate change might be playing a role in reports of larger-than-normal fish in unexpected areas.

(Video: John Farrell, Brian Monroe/The Washington Post)

The study was led by Lijing Cheng of the Chinese Academy of Sciences with numerous collaborators at institutions in China, Italy, New Zealand and the United States.

It is based on two separate ocean heat data sets, one from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and one from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Both find 2022 to be the hottest year on record for the oceans, followed by 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2017.

A multitude of consequences flow from the fast warming of the oceans.

Some are analogous to what is happening in the atmosphere.

For instance, with the average temperature of the entire ocean warmer, it increases the odds of extremes in the form of ocean heat waves in certain regions.

Just like in the case of atmospheric heat waves over land, these can be very dangerous for living organisms.

“Some of the most productive and biodiverse marine ecosystems, like coral reefs and kelp forests, are very sensitive to temperature.

We’re witnessing a real-life experiment to find out how resilient they are, how capable of adapting or migrating,” Rasmussen said.

It is based on two separate ocean heat data sets, one from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and one from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Both find 2022 to be the hottest year on record for the oceans, followed by 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2017.

A multitude of consequences flow from the fast warming of the oceans.

Some are analogous to what is happening in the atmosphere.

For instance, with the average temperature of the entire ocean warmer, it increases the odds of extremes in the form of ocean heat waves in certain regions.

Just like in the case of atmospheric heat waves over land, these can be very dangerous for living organisms.

“Some of the most productive and biodiverse marine ecosystems, like coral reefs and kelp forests, are very sensitive to temperature.

We’re witnessing a real-life experiment to find out how resilient they are, how capable of adapting or migrating,” Rasmussen said.

(Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Other consequences of ocean warming are quite different from what happens in the atmosphere.

Warm ocean water expands, raising sea levels around the globe.

At the same time, this expanding surface warm water is lighter and more buoyant than colder deeper water — which means that, in the words of scientists, the ocean becomes more stratified.

Warm and cold layers mix less, which in turn traps heat at the surface — speeding the planet’s warming — while depriving the deeper ocean of oxygen and nutrients that cannot mix downward.

The ocean also loses oxygen because warmer water cannot hold as much of it, potentially leading to low oxygen zones that are a threat to marine life.

The ocean also grows more salty in many regions, as the evaporation of warmer water leaves behind more salt — but in other regions, it actually grows fresher as rainfall increases.

The study calls it a “salty gets saltier, fresh gets fresher pattern,” as evaporation wins out in some regions and rainfall in others.

Still, that’s just the beginning of the implications.

Kevin Trenberth, a co-author of the study and a scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said the warming happening in the ocean can have direct consequences for events unfolding on land.

For instance, he said, warmer water at the top levels of the ocean can help fuel more intense storms and the torrential rainfall that accompanies them.

“Those upper sea surface temperatures have really serious consequences for any storm that comes along,” he said, adding, “I think we are seeing some of the repercussions of that in the storms that are hitting California … The heavy rainfalls are a direct consequence of this upper ocean heat content anomaly.”

In part, that is because more heat amounts to more moisture in the air, which can supercharge any storms that materialize.

For every degree Fahrenheit that the air temperature increases, the atmosphere can hold about 4 percent more water.

“The simplest way to think of this is, let’s assume the weather system and everything is going as it used to, but now we have a warmer ocean,” he said.

“The atmosphere can hold more moisture.

The warmer the atmosphere gets, the more moisture it can hold.”

9 after another powerful storm hit California’s coast in Aptos.

(Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

The new research suggests that ocean warming, while strong and steady overall, does vary markedly around the globe — with particularly rapid increases in heat in the Atlantic region off the U.S.

coastline.

This is amplifying coastal sea level rise and may also be implicated in a strong warming trend affecting the coastal northeastern United States on land.

“The Atlantic has been warming in spectacular fashion as a whole,” Trenberth said.

Wednesday’s study is the latest in a growing body of evidence that details the steady, relentless warming of the oceans.

A study published in October in Nature Reviews found that the upper reaches of the oceans have been heating up around the planet since at least the 1950s, with the most stark changes observed in the Atlantic and Southern oceans.

The authors wrote that data shows the heating has both accelerated over time and increasingly has reached deeper and deeper depths.

That warming — which the scientists said probably is irreversible through 2100 — is poised to continue and create new hot spots around the globe, especially if humans don’t make significant and rapid cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

In its most recent assessment, the U.N.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) wrote that it is “virtually certain” that the upper levels of the oceans have warmed over the past half-century and “extremely likely that human influence is the main driver.” Humans-caused emissions “are the main driver of current global acidification of the surface open ocean,” the panel wrote.

The greenhouse gas emissions that humans have produced since 1750 “have committed the global ocean to future warming,” the IPCC authors found.

Over the remainder of the 21st century, the group said, ocean warming probably will be several times what it has been over the past five decades.

Trenberth reiterated that not all ocean warming happens equally.

Storms can move heat from water to the atmosphere, currents redistribute heat around the globe, and just as worrisome hot spots emerge, so do cool spots, such as a notorious ocean region south of Greenland that has actually shown a decrease in temperature over time.

Despite the variability, there is no doubt that oceans on the whole are growing warmer over time — or what is driving that change.

“The human impact is clear when you look at the global picture,” Trenberth said.

“The global ocean heat content is going up steadily.”

Links :

Tuesday, January 17, 2023

The world’s oldest map of the night sky was amazingly accurate

This colored version of a 19th-century engraving depicts ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus using a sighting tool to measure the positions of the stars.

Science historians don't know exactly how Hipparchus measured the stars in the second century B.C., but recently discovered fragments from his star catalog reveal the remarkable accuracy of his work.

NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES, ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Science historians don't know exactly how Hipparchus measured the stars in the second century B.C., but recently discovered fragments from his star catalog reveal the remarkable accuracy of his work.

NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES, ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

From NationalGeographic by Jay Bennett

Newly discovered fragments of 2,200-year-old star coordinates—once thought lost—reveal the incredible skill of the ancient astronomer Hipparchus.

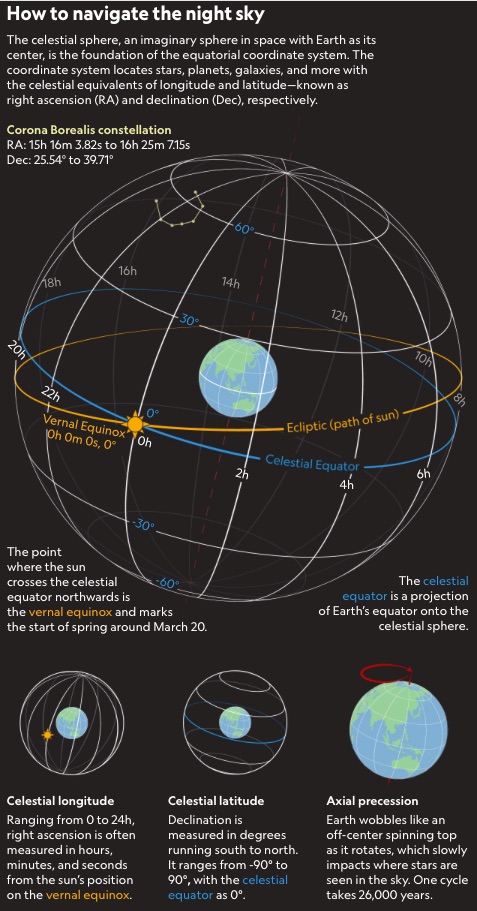

Some 2,200 years ago, the Greek astronomer Hipparchus helped establish a new way of understanding the motions of the stars that persists to this day.

By imagining Earth at the center of a celestial sphere, he used a coordinate system similar to latitude and longitude, which had recently been devised, to measure the precise positions of the stars.

“He was arguably the greatest ancient astronomer.

At least the greatest known to us by name,” says Victor Gysembergh, a science historian at the French National Center for Scientific Research.

Many ancient Greek scientists believed that Earth was literally at the center of the universe, and the stars and other celestial bodies rotated around it, although a model with Earth orbiting the sun was proposed in the 3rd century B.C.

Although this geocentric model is incorrect, the concept, which Hipparchus used to create the first known star catalog, is still used by scientists to map objects in the sky.

Hipparchus’s star catalog is the oldest known attempt to document the positions of as many objects in the night sky as possible, and it was the first time that two coordinates were used to pinpoint each object’s location.

But that original catalog is lost to time, and we know of it only thanks to the writings of later scientists such as Ptolemy, who created his own star catalog around 150 A.D.

and attributed an earlier one to Hipparchus.

Until now, the oldest evidence for stellar coordinates from Hipparchus was an 8th-century A.D.

Latin translation of a poem about the constellations that includes the coordinates as a kind of annotation.

Gysembergh and his colleagues recently revealed even older evidence of star coordinates from Hipparchus in a 5th- or 6th-century A.D.

Greek version of the same poem, Phenomena, originally written by the Greek poet Aratus in the 3rd century B.C.

The poem, along with the accompanying star coordinates, had been erased from a reused medieval parchment and was recovered only through multispectral imaging, which uses different wavelengths of light to highlight the removed text.

These images of the manuscript that contains “erased” fragments of Hipparchus's star catalog show how multispectral analysis can be used to reconstruct hidden text.

The later Syriac text is in black, the Greek text revealed underneath in yellow.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE COLLECTION.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE, 2021.

The later Syriac text is in black, the Greek text revealed underneath in yellow.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE COLLECTION.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE, 2021.

The coordinates for the four stars to the farthest north, south, east, and west of the constellation Corona Borealis are included, though one of them could not be recovered from the manuscript.

They were found to be accurate to within one degree of modern values—a remarkable achievement for someone working about 1,700 years before the invention of the telescope.

Charting the stars with ancient tools

Though historians don’t know exactly how Hipparchus measured the stars, he may have used an armillary sphere, which is a mechanical device with rotating rings that represent the different parts of the celestial sphere, such as the celestial equator, an imaginary plane spreading out from Earth’s equator, and the ecliptic, or the annual path that the sun appears to follow through the sky.

Hipparchus may have also used a dioptra, which is a sight that could be attached to an adjustable platform.

Ben Scott, NG Staff.

Source: NASA, International Astronomical Union

Source: NASA, International Astronomical Union

“The dioptra was a kind of surveying instrument,” says James Evans, a physicist and science historian at the University of Puget Sound in Washington State.

It “could be used for measuring angles for surveying operations, but you could imagine something like that being used also to measure angles of the sky.”

The armillary sphere, which takes its name from the Latin word for bracelet or arm band, is a sphere of concentric rings that could have sights on it.

“You could set this up and use it to measure angles.”

Hipparchus was likely influenced by the earlier work of Babylonian astronomers, who measured the distances of certain constellations from the ecliptic.

By tracking the movements of these zodiac constellations—the constellations that sit in a part of the sky that the sun moves through over the course of the year—the Babylonians could measure the seasons and predict astronomical events such as eclipses.

Combining the Babylonian practice of measuring and predicting the movements of the stars with Greek concepts of mathematics and geometry is considered the fundamental achievement of Hipparchus.

“Modern astronomy really comes from the merging of these two different approaches,” Evans says.

“The Greek approach based on geometry and philosophy of nature.

The Babylonian approach based on regular observation and in crunching numbers.”

The newly discovered coordinates represent only a small fraction of about 800 stars that Hipparchus is believed to have measured.

In total, only a few dozen coordinates survive that have been attributed to Hipparchus, but his work appears to be more accurate than Ptolemy’s later catalog.

“The sample size is admittedly small, so maybe there are errors elsewhere,” Gysembergh says.

“But as it stands, he’s more accurate than Ptolemy.”

The recent study compared the newly discovered coordinates to the values found in other sources, and they generally agreed, though some discrepancies exist, perhaps the result of different measurements or changes as the figures were transcribed through the ages.

Revealing a hidden text

The text with Hipparchus’ star coordinates is in a palimpsest, which is a document that has been written on and erased multiple times, with traces of removed writing often still detectable.

It’s part of the 10th- or 11th-century A.D.

Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a collection of parchments from St. Catherine’s monastery in Egypt with monastic writings in Syriac, an ancient language of West Asia.

The astronomical material was first detected in 2012, when biblical scholar Peter Williams at the University of Cambridge asked his students to study images of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, and one of them, Jamie Klair, noticed the Greek writing visible beneath the Syriac text.

In 2017, the parchments were photographed with state-of-the-art multispectral imaging tools to reveal the text underneath more clearly.

Some of the documents revealed fragments of Aratus’s poem, transcribed on parchment that was later scraped clean and reused for the Codex Climaci Rescriptus.

The poem is accompanied by illustrations and mythological stories about the constellations.

In 2021, while poring over the multispectral images of the poem during lockdown, Williams noticed numbers that he thought must be star coordinates.

As it turns out, they were dimensions of the constellation Corona Borealis and the coordinates for its outermost stars, likely from the first astronomer to attempt to chart the entire sky.

Clues in the stars and parchments

Using a phenomenon called precession, which is the wobble of Earth on its axis as it rotates, the researchers were able to determine that the coordinates match the positions of the stars in Corona Borealis as seen from the island of Rhodes around 130 B.C., which is where and when Hipparchus is thought to have taken most of his observations.

Hipparchus may have been amused by this, as he was also the first scientist to describe the motion of precession.

What may not have amused the ancient astronomer is the appearance of his work alongside that of the poet Aratus.

Phenomena “was a best seller in antiquity, a schoolroom classic,” Gysembergh says, and the poem remained popular into Roman times.

Hipparchus, however, was not a fan—the astronomer’s only surviving work is a criticism of Aratus’ poem for the imprecise descriptions of the constellations.

“We lost everything of Hipparchus, we have only fragments, except his commentary on Aratus, because Aratus remains so popular,” says Francesca Schironi, a classicist at the University of Michigan who studies Hipparchus’ commentary on Phenomena.

This commentary, thought to have been written by Hipparchus after he created his star catalog, also includes coordinates for some of the constellations.

The 8th-century Latin version of Aratus’ poem known as the Aratus Latinus also contains star coordinates, which the new research helps confirm also likely came from Hipparchus.

Studying more pages of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus and of other palimpsests could reveal additional lost material.

Gysembergh believes that the new star coordinates were part of a book that included Phenomena and other writings that was brought to St.

Catherine’s and later disassembled so the parchment could be reused.

While star coordinates for only one constellation were found in the medieval palimpsest, the original book may have contained the coordinates for all the constellations in Aratus’ poem.

“These technologies of multispectral imaging have only been applied to a very small fraction of the extant palimpsests.

There are literally thousands and thousands.

A lot of them have completely unidentified content,” Gysembergh says.

“We can reasonably expect to have many more such discoveries in the years to come.”

“You could set this up and use it to measure angles.”

Hipparchus was likely influenced by the earlier work of Babylonian astronomers, who measured the distances of certain constellations from the ecliptic.

By tracking the movements of these zodiac constellations—the constellations that sit in a part of the sky that the sun moves through over the course of the year—the Babylonians could measure the seasons and predict astronomical events such as eclipses.

Combining the Babylonian practice of measuring and predicting the movements of the stars with Greek concepts of mathematics and geometry is considered the fundamental achievement of Hipparchus.

“Modern astronomy really comes from the merging of these two different approaches,” Evans says.

“The Greek approach based on geometry and philosophy of nature.

The Babylonian approach based on regular observation and in crunching numbers.”

The newly discovered coordinates represent only a small fraction of about 800 stars that Hipparchus is believed to have measured.

In total, only a few dozen coordinates survive that have been attributed to Hipparchus, but his work appears to be more accurate than Ptolemy’s later catalog.

“The sample size is admittedly small, so maybe there are errors elsewhere,” Gysembergh says.

“But as it stands, he’s more accurate than Ptolemy.”

The recent study compared the newly discovered coordinates to the values found in other sources, and they generally agreed, though some discrepancies exist, perhaps the result of different measurements or changes as the figures were transcribed through the ages.

Revealing a hidden text

The text with Hipparchus’ star coordinates is in a palimpsest, which is a document that has been written on and erased multiple times, with traces of removed writing often still detectable.

It’s part of the 10th- or 11th-century A.D.

Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a collection of parchments from St. Catherine’s monastery in Egypt with monastic writings in Syriac, an ancient language of West Asia.

The astronomical material was first detected in 2012, when biblical scholar Peter Williams at the University of Cambridge asked his students to study images of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, and one of them, Jamie Klair, noticed the Greek writing visible beneath the Syriac text.

In 2017, the parchments were photographed with state-of-the-art multispectral imaging tools to reveal the text underneath more clearly.

Some of the documents revealed fragments of Aratus’s poem, transcribed on parchment that was later scraped clean and reused for the Codex Climaci Rescriptus.

The poem is accompanied by illustrations and mythological stories about the constellations.

In 2021, while poring over the multispectral images of the poem during lockdown, Williams noticed numbers that he thought must be star coordinates.

As it turns out, they were dimensions of the constellation Corona Borealis and the coordinates for its outermost stars, likely from the first astronomer to attempt to chart the entire sky.

Clues in the stars and parchments

Using a phenomenon called precession, which is the wobble of Earth on its axis as it rotates, the researchers were able to determine that the coordinates match the positions of the stars in Corona Borealis as seen from the island of Rhodes around 130 B.C., which is where and when Hipparchus is thought to have taken most of his observations.

Hipparchus may have been amused by this, as he was also the first scientist to describe the motion of precession.

What may not have amused the ancient astronomer is the appearance of his work alongside that of the poet Aratus.

Phenomena “was a best seller in antiquity, a schoolroom classic,” Gysembergh says, and the poem remained popular into Roman times.

Hipparchus, however, was not a fan—the astronomer’s only surviving work is a criticism of Aratus’ poem for the imprecise descriptions of the constellations.

“We lost everything of Hipparchus, we have only fragments, except his commentary on Aratus, because Aratus remains so popular,” says Francesca Schironi, a classicist at the University of Michigan who studies Hipparchus’ commentary on Phenomena.

This commentary, thought to have been written by Hipparchus after he created his star catalog, also includes coordinates for some of the constellations.

The 8th-century Latin version of Aratus’ poem known as the Aratus Latinus also contains star coordinates, which the new research helps confirm also likely came from Hipparchus.

Studying more pages of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus and of other palimpsests could reveal additional lost material.

Gysembergh believes that the new star coordinates were part of a book that included Phenomena and other writings that was brought to St.

Catherine’s and later disassembled so the parchment could be reused.

While star coordinates for only one constellation were found in the medieval palimpsest, the original book may have contained the coordinates for all the constellations in Aratus’ poem.

“These technologies of multispectral imaging have only been applied to a very small fraction of the extant palimpsests.

There are literally thousands and thousands.

A lot of them have completely unidentified content,” Gysembergh says.

“We can reasonably expect to have many more such discoveries in the years to come.”

Links :

Monday, January 16, 2023

Compound derived from B.C. sea sponge could block COVID-19 virus, researchers find

Glass sponge reefs can grow 20 to 30 metres high and serve as the habitat for a variety of fish.

Glass sponge reefs can grow 20 to 30 metres high and serve as the habitat for a variety of fish.UBC researchers say a compound derived from sea sponges found off the B.C. coast can block coronavirus infection in human cells.

(Glen Dennison)

From CBC

3 most effective natural compounds in catalogue of 350 were sourced in Canada, UBC team says

Researchers at the University of British Columbia say a compound derived from sea sponges found off the B.C. coast can block coronavirus infection in human cells.

The discovery could pave the way for the development of new COVID-19 medicines made from natural sources, researchers say.

An international team led by UBC scientists analyzed a catalogue of more than 350 compounds derived from natural sources that included plants, fungi and marine sponges in an effort to find new antiviral drugs to treat coronavirus variants.

Researchers bathed human lung cells in solutions made from the compounds and then infected the cells with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

They found 26 compounds reduced viral infection in the cells.

The three most effective compounds were sourced in Canada: one from sea sponges collected in Howe Sound, northwest of Vancouver, another from marine bacteria collected in Barkley Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and a third from marine bacteria in Newfoundland.

"These compounds blocked infection, so we cannot see more virus in the cells after a few days," said Jimena Pérez-Vargas, a research associate in UBC's department of microbiology and immunology.

Wastewater from some flights arriving at Vancouver airport to be tested for COVID-19

"They are very efficient because we need to use very small amounts of these compounds to block completely the infection of the virus in the cells."

Pérez-Vargas says the compounds are promising in that they target cells rather than the virus, blocking the virus from replicating and helping the cell to recover.

She says researchers are able to replicate the compound found in sea sponges so it won't be necessary to harvest them.

The peer-reviewed paper was published in the journal Antiviral Research.

'More work to do': researcher Pérez-Vargas says they are pleased with their findings "but we have more work to do."

She says the results have come at the cellular level and the next step is to test them on animal models.

Dr. Srinivas Murthy, an infectious diseases expert in UBC's faculty of medicine who was not affiliated with the study, says it's always exciting to find new molecules that could work against viruses.

"These compounds blocked infection, so we cannot see more virus in the cells after a few days," said Jimena Pérez-Vargas, a research associate in UBC's department of microbiology and immunology.

Wastewater from some flights arriving at Vancouver airport to be tested for COVID-19

"They are very efficient because we need to use very small amounts of these compounds to block completely the infection of the virus in the cells."

Pérez-Vargas says the compounds are promising in that they target cells rather than the virus, blocking the virus from replicating and helping the cell to recover.

She says researchers are able to replicate the compound found in sea sponges so it won't be necessary to harvest them.

The peer-reviewed paper was published in the journal Antiviral Research.

'More work to do': researcher Pérez-Vargas says they are pleased with their findings "but we have more work to do."

She says the results have come at the cellular level and the next step is to test them on animal models.

Dr. Srinivas Murthy, an infectious diseases expert in UBC's faculty of medicine who was not affiliated with the study, says it's always exciting to find new molecules that could work against viruses.

Dr. Jimena Pérez-Vargas of the University of British Columbia is the co-author of a study that says a compound derived from sea sponges found off the B.C. coast blocks some COVID-19 infections.

(Paul Joseph/The University of British Columbia)

"It's reassuring that there's still work being done in this space ... there's lots of things that we still have to learn about how COVID works and the possible therapeutics that are out there," Murthy said.

Even if the findings don't lead directly to a treatment for humans, it could help scientists better understand the disease, he says.

"Scientists from around the world can see this paper and think, OK, I have something similar, let's adapt what we're doing and build toward something that could work for everybody," he says.

The study notes that natural products are "considered a rich resource for novel antiviral drug development" and "have the advantage of more favourable toxicological profiles, fewer side effects, and a faster approval process in comparison to chemically engineered drugs."

Murthy says the study speaks to the importance of "maintaining biodiversity because there's so many medicinal products that exist out there in the natural environment."

The antimalarial drug Artemisinin, for instance, was extracted from sweet wormwood. Farnesol, which is found in fruits and herbs, is being studied as a potential treatment for Parkinson's Disease.

"I think the ability to find new medicines is truly exciting," he said.

Links :

Sunday, January 15, 2023

Bishop Rock : a Scilly island

Twenty-eight miles from Cornwall is Bishop Rock.

Localization with the GeoGarage platform (UKHO raster chart)

This tiny island is in the Guinness Book of Records as the smallest island with a building on Earth.

A storm destroyed the original lighthouse in 1847, but builders completed the current lighthouse in 1858.

Impressively, this lighthouse is tied with Eddystone Lighthouse for the tallest lighthouse in England.

This was shot on video tape with a fisheye lens, in the 1990's.

I got a helicopter ride out with the crew who were about to automate the place.

So i only had a few hours on site.

This was also the 1st time I had been back from when I was stationed here in the 80's.

I was a Lighthouse Keeper from 1974 to 1997.

(Peter Halil)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)